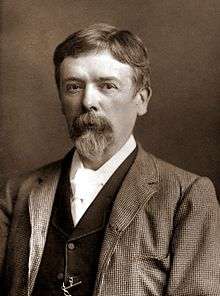

George du Maurier

| George du Maurier | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

George Louis Palmella Busson du Maurier 6 March 1834 Paris |

| Died |

8 October 1896 (aged 62) Hampstead, London |

| Occupation | Cartoonist and author |

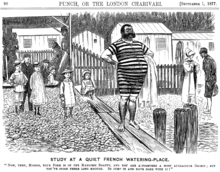

Cartoon by du Maurier from Punch.

George Louis Palmella Busson du Maurier (6 March 1834 – 8 October 1896) was a French-British cartoonist and author, known for his cartoons in Punch and also for his novel Trilby. He was the father of actor Gerald du Maurier and grandfather of the writers Angela du Maurier and Dame Daphne du Maurier. He was also the father of Sylvia Llewelyn Davies and grandfather of the five boys who inspired J.M. Barrie's Peter Pan.

Early life

George du Maurier was born in Paris, the son of Louis-Mathurin du Maurier and Ellen Clarke, daughter of the Regency courtesan Mary Anne Clarke. He was brought up to believe that his aristocratic grandparents fled France during the Revolution, leaving vast estates behind in France, to live in England as émigrés. However, du Maurier's grandfather, Robert Mathurin, was actually a tradesman who left Paris in 1789 to avoid fraud charges, and later changed the family name to du Maurier. [1]

Du Maurier studied art in Paris, and moved to Antwerp, Belgium, where he lost vision in his left eye. He consulted an oculist in Düsseldorf, Germany, where he met his future wife, Emma Wightwick. He followed her family to London, where he married Emma in 1863. The couple settled in Hampstead around 1877, first in Church Row and later at New Grove House.[2] They had five children: Beatrix (known as Trixy), Guy, Sylvia, Marie Louise (known as May) and Gerald.

Career

Cartoonist

He became a member of the staff of the British satirical magazine Punch in 1865, drawing two cartoons a week. His most common targets were the affected manners of Victorian society, the bourgeoisie and members of Britain's growing Middle Class in particular. His most enduringly famous cartoon, True Humility, was the origin of the expressions "good in parts" and "a curate's egg". (In the caption, a bishop addresses a curate [a very humble class of clergyman] whom he has condescended to invite to breakfast: "I'm afraid you've got a bad egg, Mr. Jones. The curate replies, "Oh no, my Lord, I assure you – parts of it are excellent!") In an earlier (1884) cartoon, du Maurier had coined the expression "bedside manner" by which he satirized actual medical skill. Another of du Maurier's notable cartoons was of a videophone conversation in 1879, using a device he called "Edison's telephonoscope".

In addition to producing black-and-white drawings for Punch, du Maurier created illustrations for several other popular periodicals: Harper's, The Graphic, The Illustrated Times, The Cornhill Magazine, and the religious periodical Good Words.[3] Furthermore he did illustrations for the serialization of Charles Warren Adams's The Notting Hill Mystery, which is thought to be the first detective story of novel length to have appeared in English.[4] Among several other novels he illustrated was Misunderstood by Florence Montgomery in 1873.[5]

Writer

Owing to his deteriorating eyesight, du Maurier reduced his involvement with Punch in 1891 and settled in Hampstead, where he wrote three novels. His first, Peter Ibbetson, was a modest success at the time and later adapted to stage and screen, most notably in Peter Ibbetson, and as an opera.

His second novel Trilby, was published in 1894. It fitted into the gothic horror genre which was undergoing a revival during the fin de siècle, and the book was hugely popular. The story of the poor artist's model Trilby O'Ferrall, transformed into a diva under the spell of the evil musical genius Svengali, created a sensation. Soap, songs, dances, toothpaste, and even the city of Trilby in Florida, were all named for the heroine, and the variety of soft felt hat with an indented crown that was worn in the London stage dramatization of the novel, is known to this day as a trilby. The plot inspired Gaston Leroux's 1910 novel Phantom of the Opera and the innumerable works derived from it. Du Maurier eventually came to dislike the persistent attention given to his novel.

The third novel was a long, largely autobiographical work entitled The Martian, which was only published posthumously (1896).

Personal life and death

George du Maurier was a close friend of Henry James, the novelist; their relationship was fictionalised in David Lodge's Author, Author.

He was buried in St John-at-Hampstead churchyard in Hampstead parish in London.

Illustration by du Maurier for Punch magazine, 17 March 1866, parodying Pre-Raphaelitism.

Bibliography

- Peter Ibbetson (novel) – 1891, adapted in 1935 by Henry Hathaway, in a film starring Gary Cooper

- Trilby – 1894

- The Martian – 1897

- Social Pictorial Satire- 1898 (Harper's New Monthly Magazine)

References

- ↑ http://www.victorianweb.org/art/illustration/dumaurier/pva95.html

- ↑ Borer, Mary Cathcart. (1976) Hampstead and Highgate: The story of two hilltop villages. London: W.H. Allen, p. 169. ISBN 0491018274

- ↑ Souter, Nick and Tessa (2012). The Illustration Handbook: A guide to the world's greatest illustrators. Oceana. p. 32. ISBN 9781845734732.

- ↑ The original edition illustrated is available at the Internet Archive: Section 1 Retrieved 1 February 2013. Once a Week, Vol. 7, p. 617, 29 November 1862 and at weekly intervals.

- ↑ The Feminist Companion to Literature in English, eds Virginia Blain, Patricia Clements and Isobel Grundy (London: Batsford, 1990), p. 752.

Further reading

- Richard Kelly. George du Maurier. Twayne, 1983.

- Richard Kelly. The Art of George du Maurier. Scolar Press, 1996.

- Leonée Ormond. George du Maurier. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1969.

- "Du Maurier", a poem by Florence Earle Coates first published in 1898.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to George du Maurier. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: George du Maurier |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: George Du Maurier |

- A gallery of George du Maurier works for Punch magazine

- George du Maurier at The Victorian Web

- George du Maurier at Lambiek.net

- Works by George Du Maurier at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about George du Maurier at Internet Archive

- Works by George du Maurier at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- George du Maurier's cartoon Love-Agony satirizing the Aesthetic Movement and Oscar Wilde.

- George du Maurier cartoons at CartoonStock (Commercial site)

- Telephonoscope, a cartoon of a television/videophone in 1879

- Archival material relating to George du Maurier listed at the UK National Archives

- Portraits of George Louis Palmella Busson Du Maurier at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Blue Plaque at 91, Great Russell Street, Bloomsbury, London

|