Charles George Gordon

| Charles George Gordon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s) | Chinese Gordon, Gordon Pasha, Gordon of Khartoum |

| Born |

28 January 1833 London, England |

| Died |

26 January 1885 (aged 51) Khartoum, Sudan |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1852–1885 |

| Rank | Major General |

| Commands held | Governor-General of the Sudan |

| Battles/wars |

Crimean War Siege of Sevastopol Battle of Kinburn Second Opium War Taiping Rebellion Battle of Cixi Battle of Changzhou Mahdist War Siege of Khartoum |

| Awards |

Order of the Double Dragon |

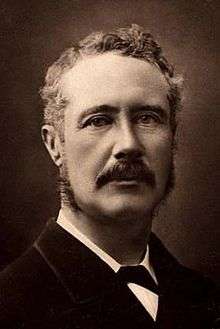

Major-General Charles George Gordon, CB (28 January 1833 – 26 January 1885), also known as Chinese Gordon, Gordon Pasha, and Gordon of Khartoum, was a British Army officer and administrator.

He saw action in the Crimean War as an officer in the British Army. But he made his military reputation in China, where he was placed in command of the "Ever Victorious Army," a force of Chinese soldiers led by European officers. In the early 1860s, Gordon and his men were instrumental in putting down the Taiping Rebellion, regularly defeating much larger forces. For these accomplishments, he was given the nickname "Chinese" Gordon and honours from both the Emperor of China and the British.

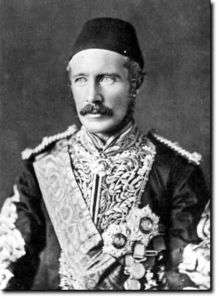

He entered the service of the Khedive in 1873 (with British government approval) and later became the Governor-General of the Sudan, where he did much to suppress revolts and the slave trade. Exhausted, he resigned and returned to Europe in 1880.

A serious revolt then broke out in the Sudan, led by a Muslim religious leader and self-proclaimed Mahdi, Muhammad Ahmad. Gordon had been sent to Khartoum with instructions to secure the evacuation of loyal soldiers and civilians and to depart with them. However, after evacuating about 2,500 British civilians, in defiance of those instructions, he retained a smaller group of soldiers and non-military men. In the buildup to battle, the two leaders corresponded, each attempting to convert the other to his faith, but neither would accede. Besieged by the Mahdi's forces, Gordon organized a city-wide defence lasting almost a year that gained him the admiration of the British public, but not of the government, which had wished him not to become entrenched. Only when public pressure to act had become irresistible did the government, with reluctance, send a relief force. It arrived two days after the city had fallen and Gordon had been killed.

Early life

Gordon was born in Woolwich, London, a son of Major-General Henry William Gordon (1786–1865) and Elizabeth (Enderby) Gordon (1792–1873). He was educated at Fullands School in Taunton, Somerset, Taunton School, and the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich. In 1852, he was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Royal Engineers, completing his training at Chatham, and in 1854 he was promoted to full lieutenant.

Gordon was first assigned to construct fortifications at Milford Haven, Pembrokeshire, Wales. When the Crimean War began, he was sent to the Russian Empire, arriving at Balaklava in January 1855. He was put to work in the Siege of Sevastopol and took part in the assault of the Redan from 18 June to 8 September. Gordon took part in the expedition to Kinburn, and returned to Sevastopol at the war's end. For his services in the Crimea, he received the Crimean war medal and clasp.[1] For the same services he was appointed a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour by the Government of France on 16 July 1856.[2][3]

Following the peace, he was attached to an international commission to mark the new border between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire in Bessarabia. He continued surveying, marking off the boundary into Asia Minor. Gordon returned to Britain in late 1858, and was appointed as an instructor at Chatham. He was promoted to captain in April 1859.[1]

China

In 1860 General Gordon volunteered to serve in China.[4] He arrived at Tianjin in September 1859. He was present at the occupation of Beijing and at the destruction of the Summer Palace. The British forces occupied northern China until April 1862, then under General Charles William Dunbar Staveley, withdrew to Shanghai to protect the European settlement from the rebel Taiping army.

Following the successes in the 1850s in the provinces of Guangxi, Hunan and Hubei, and the capture of Nanjing in 1853 the rebel advance had slowed. For some years, the Taipings gradually advanced eastwards, but eventually they came close enough to Shanghai to alarm the European inhabitants. A militia of Europeans and Asians was raised for the defence of the city and placed under the command of an American, Frederick Townsend Ward, and occupied the country to the west of Shanghai.[5]

The British arrived at a crucial time. Staveley decided to clear the rebels within 30 miles (48 km) of Shanghai in cooperation with Ward and a small French force.[5] Gordon was attached to his staff as engineer officer. Jiading, northwest suburb of present Shanghai, Qingpu and other towns were occupied, and the area was fairly cleared of rebels by the end of 1862.[5]

Ward was killed in the Battle of Cixi and his successor H. A. Burgevine, an American was disliked by the Imperial Chinese authorities.[6] Li Hongzhang, the governor of the Jiangsu province, requested Staveley to appoint a British officer to command the contingent. Staveley selected Gordon, who had been made a brevet major in December 1862 and the nomination was approved by the British government.[6] In March 1863 Gordon took command of the force at Songjiang, which had received the name of "Ever Victorious Army."[6] Without waiting to reorganize his troops, Gordon led them at once to the relief of Chansu, a town 40 miles northwest of Shanghai. The relief was successfully accomplished and Gordon quickly won the respect of his troops. His task was made easier by innovative military ideas Ward had implemented in the Ever Victorious Army.

Gordon then reorganized his force and advanced against Kunshan, which was captured at considerable loss. Gordon then took his force through the country, seizing towns until, with the aid of Imperial troops, the city of Suzhou was captured in November.[6] Following a dispute with Li Hongzhang over the execution of rebel leaders, Gordon withdrew his force from Suzhou and remained inactive at Kunshan until February 1864.[6] Gordon then made a rapprochement with Li and visited him in order to arrange for further operations. The "Ever-Victorious Army" resumed its high tempo advance, leading to the Battle of Changzhou, and culminating in the capture of Changzhou Fu, the principal military base of the Taipings in the region. Gordon then returned to Kunshan and disbanded his army.

The Emperor promoted Gordon to the rank of tidu (提督: "Chief commander of Jiangsu province"), decorated him with the imperial yellow jacket, and raised him to Qing's Viscount first class but Gordon declined an additional gift of 10,000 taels of silver from the imperial treasury.[7] The British Army promoted Gordon to lieutenant-colonel and he was made a Companion of the Order of the Bath. He also gained the popular nickname "Chinese" Gordon.

Service with the Khedive

Gordon returned to Britain and commanded the Royal Engineers' efforts around Gravesend, Kent to erect forts for the defence of the River Thames. Following the death of his father he undertook extensive social work in the town including teaching at the local ragged school [8] and donated the gardens of his official residence Fort House (now a museum) to the town. In October 1871, he was appointed British representative on the international commission to maintain the navigation of the mouth of the River Danube, with headquarters at Galatz. In 1872, Gordon was sent to inspect the British military cemeteries in the Crimea, and when passing through Constantinople he made the acquaintance of the Prime Minister of Egypt, who opened negotiations for Gordon to serve under the Khedive, Ismail Pasha. In 1873, Gordon received a definite offer from the Khedive, which he accepted with the consent of the British government, and proceeded to Egypt early in 1874. Gordon was made a colonel in the Egyptian army. The Egyptian authorities had been extending their control southwards since the 1820s. An expedition was sent up the White Nile, under Sir Samuel Baker, which reached Khartoum in February 1870 and Gondokoro in June 1871. Baker met with great difficulties and managed little beyond establishing a few posts along the Nile. The Khedive asked for Gordon to succeed Baker as governor of the region. After a short stay in Cairo, Gordon proceeded to Khartoum via Suakin and Berber. From Khartoum, he proceeded up the White Nile to Gondokoro.

Gordon remained in the Gondokoro provinces until October 1876. He had succeeded in establishing a line of way stations from the Sobat confluence on the White Nile to the frontier of Uganda, where he proposed to open a route from Mombasa. In 1874 he built the station at Dufile on the Albert Nile to reassemble steamers carried there past rapids for the exploration of Lake Albert. Moreover, considerable progress was made in the suppression of the slave trade.[9] However, Gordon had come into conflict with the Egyptian governor of Khartoum and Sudan. The clash led to Gordon informing the Khedive that he did not wish to return to the Sudan, and he left for London. Ismail Pasha wrote to him saying that he had promised to return, and that he expected him to keep his word. Gordon agreed to return to Cairo, and was asked to take the position of Governor-General of the entire Sudan, which he accepted. He thereafter received the honorific rank and title of a pasha in the local aristocracy.

Governor-General of the Sudan

As governor, Gordon faced a variety of challenges. During the 1870s, European initiatives against the slave trade caused an economic crisis in northern Sudan, precipitating increasing unrest. Relations between Egypt and Abyssinia (later renamed Ethiopia) had become strained due to a dispute over the district of Bogos, and war broke out in 1875. An Egyptian expedition was completely defeated near Gundet. A second and larger expedition under Prince Hassan was sent the following year and was routed at Gura. Matters then remained quiet until March 1877, when Gordon proceeded to Massawa, hoping to make peace with the Abyssinians. He went up to Bogos and wrote to the king proposing terms. However, he received no reply as the king had gone southwards to fight with the Shoa. Gordon, seeing that the Abyssinian difficulty could wait, proceeded to Khartoum.

An insurrection had broken out in Darfur and Gordon went to deal with it. The insurgents were numerous, and he saw that diplomacy had a better chance of success. Gordon, accompanied only by an interpreter, rode into the enemy camp to discuss the situation. This bold move proved successful, as many of the insurgents joined him, though the remainder retreated to the south. Gordon visited the provinces of Berber and Dongola, and then returned to the Abyssinian frontier, before ending up back in Khartoum in January 1878. Gordon was summoned to Cairo, and arrived in March to be appointed president of a commission. The Khedive was deposed in 1879 in favor of his son.

Gordon returned south and proceeded to Harrar, south of Abyssinia, and, finding the administration in poor standing, dismissed the governor. He then returned to Khartoum, and went again into Darfur to suppress the slave traders. His subordinate, Gessi Pasha, fought with great success in the Bahr-el-Ghazal district in putting an end to the revolt there. Gordon then tried another peace mission to Abyssinia. The matter ended with Gordon's imprisonment and transfer to Massawa. Thence he returned to Cairo and resigned his Sudan appointment. He was exhausted by years of incessant work.

In March 1880, he recovered for a couple of weeks in the Hotel du Faucon in Lausanne, 3 Rue St Pierre, famous for its views on Lake Geneva and because several celebrities had stayed there, such as Giuseppe Garibaldi, one of Gordon's heroes,[10] and possibly one of the reasons Gordon had chosen this hotel. In the hotel's restaurant, now a pub called Happy Days, he met another guest from England, the reverend R.H. Barnes, vicar of Heavitree near Exeter, who became a good friend. After Gordon's death Barnes co-authored Charles George Gordon: A Sketch (1885), which begins with the meeting at the hotel in Lausanne.

Other offers

On 2 March 1880, on his way from London to Switzerland, Gordon had visited King Leopold II of Belgium in Brussels and was invited to take charge of the Congo Free State. In April, the government of the Cape Colony offered him the position of commandant of the Cape local forces. In May, the Marquess of Ripon, who had been given the post of Governor-General of India, asked Gordon to go with him as private secretary. Gordon accepted the offer, but shortly after arriving in India, he resigned.

Hardly had he resigned when he was invited by Sir Robert Hart, inspector-general of customs in China, to Beijing. He arrived in China in July and met Li Hongzhang, and learned that there was risk of war with Russia. Gordon proceeded to Beijing and used all his influence to ensure peace.

Gordon returned to Britain and rented an apartment on 8 Victoria Grove in London. But in April 1881 he left for Mauritius as Commander, Royal Engineers. He remained in Mauritius until March 1882, when he was promoted to major-general. He was sent to the Cape to aid in settling affairs in Basutoland, but he returned to the United Kingdom after only a few months.

Being unemployed, Gordon decided to go to Palestine,[11] a region he had long desired to visit, where he would remain for a year (1882–83). After his visit, Gordon suggested in his book Reflections in Palestine a different location for Golgotha, the site of Christ's crucifixion. The site lies north of the traditional site at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and is now known as "The Garden Tomb," or sometimes as "Gordon's Calvary." Gordon's interest was prompted by his religious beliefs, as he had become an evangelical Christian in 1854.[12]

King Leopold II then asked him again to take charge of the Congo Free State. He accepted and returned to London to make preparations, but soon after his arrival the British requested that he proceed immediately to the Sudan, where the situation had deteriorated badly after his departure—another revolt had arisen, led by the self-proclaimed Mahdi, Mohammed Ahmed.

Mahdist uprising

_Major-General_Charles_George_Gordon_greeting_reinforcements_at_Khartoum_in_1885-_TIMEA.jpg)

The Egyptian forces in the Sudan were insufficient to cope with the rebels, and the northern government was occupied in the suppression of the Urabi Revolt. By September 1882, the Sudanese position had grown perilous. In December 1883, the British government ordered Egypt to abandon the Sudan, but that was difficult to carry out, as it involved the withdrawal of thousands of Egyptian soldiers, civilian employees, and their families. The British government asked Gordon to proceed to Khartoum to report on the best method of carrying out the evacuation.

Gordon started for Cairo in January 1884, accompanied by Lt. Col. J. D. H. Stewart. At Cairo, he received further instructions from Sir Evelyn Baring, and was appointed governor-general with executive powers. Traveling through Korosko and Berber, he arrived at Khartoum on 18 February, where he offered his earlier foe, the slaver-king Sebehr Rahma, release from prison in exchange for leading troops against Ahmed.[14] Gordon commenced the task of sending the women and children and the sick and wounded to Egypt, and about 2,500 had been removed before the Mahdi's forces closed in. Gordon hoped to have the influential local leader Sebehr Rahma appointed to take control of Sudan, but the British government refused to support a former slaver.

The advance of the rebels against Khartoum was combined with a revolt in the eastern Sudan. Because the Egyptian troops at Suakin were repeatedly defeated, a British force was sent to Suakin under General Sir Gerald Graham, which drove the rebels away in several hard-fought actions. Gordon urged that the road from Suakin to Berber be opened, but his request was refused by the government in London, and in April Graham and his forces were withdrawn and Gordon and the Sudan were abandoned. The garrison at Berber surrendered in May, and Khartoum was completely isolated.

Gordon energetically organized the defence of Khartoum. A siege by the Mahdist forces started on 18 March 1884. The British had decided to abandon the Sudan, but it was clear that Gordon had other plans, and the public increasingly called for a relief expedition. It was not until August that the government decided to take steps to relieve Gordon, and only by November was the British relief force, called the Nile Expedition, or, more popularly, the Khartoum Relief Expedition or Gordon Relief Expedition (a title that Gordon strongly deprecated), under the command of Field Marshal Garnet Wolseley, ready.

The force consisted of two groups, a "flying column" of camel-borne troops from Wadi Halfa. The troops reached Korti towards the end of December, and arrived at Metemma on 20 January 1885. There they found four gunboats which had been sent north by Gordon four months earlier, and prepared them for the trip back up the Nile. On 24 January two of the steamers, carrying 20 soldiers of the Sussex Regiment wearing red tunics to clearly identify them as British, were sent on a reconnaissance mission to Khartoum, with orders from Wolseley not to attempt to rescue Gordon or bring him ammunition or food.[15] On arriving at Khartoum on 28 January, they found that the city had been captured and Gordon had been killed just two days before, coincidentally, two days before his 52nd birthday. Under heavy fire from Dervish warriors on the bank, the two steamers turned back up-river.

The British press criticized the relief force for arriving two days late, but it was later argued that the Mahdi's forces had good intelligence, and if the camel corps had advanced earlier, the final attack on Khartoum would also have come earlier. Finally, the boats sent were not there to relieve Gordon, who was not expected to agree to abandon the city, and the small force and limited supplies on board could have offered scant military support for the besieged in any case.[15]

Death

The manner of his death is uncertain, but it was romanticized in a popular painting by George William Joy - General Gordon's Last Stand (1885, currently in the Leeds City Art Gallery), and again in the film Khartoum (1966) with Charlton Heston as Gordon.

Gordon was apparently killed at the Governor-General's palace about an hour before dawn. As recounted in Bernard M. Allen’s article "How Khartoum Fell" (1941), the Mahdi had given strict orders to his three Khalifas not to kill Gordon. However, the orders were not obeyed. Gordon died on the steps of a stairway in the northwestern corner of the palace, where he and his personal bodyguard, Agha Khalil Orphali, had been firing at the enemy. Orphali was knocked unconscious and did not see Gordon die. When he woke up again that afternoon, he found Gordon's body covered with flies and the head cut off.[16] A merchant, Bordeini Bey, glimpsed Gordon standing on the palace steps in a white uniform looking into the darkness. Reference is made to an 1889 account of the General surrendering his sword to a senior Mahdist officer, then being struck and subsequently speared in the side as he rolled down the staircase.[17] When Gordon's head was unwrapped at the Mahdi's feet, he ordered the head transfixed between the branches of a tree ". . . where all who passed it could look in disdain, children could throw stones at it and the hawks of the desert could sweep and circle above." His body was desecrated and thrown down a well.[18] After the reconquest of the Sudan, in 1898, several attempts were made to locate Gordon's remains, but in vain.

In the hours following Gordon's death an estimated 10,000 civilians and members of the garrison were killed in Khartoum.[18] The massacre was finally halted by orders of the Mahdi.

Many of Gordon's papers were saved and collected by two of his sisters, Helen Clark Gordon, who married Gordon's medical colleague in China, Dr. Moffit, and Mary, who married Gerald Henry Blunt. Gordon's papers, as well as some of his grandfather's (Samuel Enderby III), were accepted by the British Library around 1937.

The failure to rescue General Gordon's force in Sudan was a major blow to Prime Minister Gladstone's popularity. Queen Victoria sent him a telegram of rebuke which found its way into the press. Critics said Gladstone had neglected military affairs and had not acted promptly enough to save the besieged Gordon. Critics inverted his acronym, "G.O.M." (for "Grand Old Man"), to "M.O.G." (for "Murderer of Gordon"). He resigned later that year and his party was defeated in the subsequent general election.

Memorials

News of Gordon's death led to an "unprecedented wave of public grief across Britain." A memorial service, conducted by the Bishop of Newcastle, was held at St. Paul's Cathedral on 14 March. The Lord Mayor of London opened a public subscription to raise funds for a permanent memorial to Gordon; this eventually materialized as the Gordon Boys Home, now Gordon's School, in West End, Woking.[19][20]

Statues were erected in Trafalgar Square, London, in Chatham, Gravesend, Melbourne (Australia), and Khartoum. Southampton, where Gordon had stayed with his sister, Augusta, in Rockstone Place before his departure to the Sudan, erected a memorial in Porter's Mead, now Queen's Park, near the town's docks.[19] On 16 October 1885, the "light and elegant structure" was unveiled; it comprises a stone base on which there are four polished red Aberdeen granite columns, about twenty feet high. The columns are surmounted by carved capitals supporting a cross. The pedestal bears the arms of the Gordon clan and of the borough of Southampton, and also Gordon’s name in Chinese. Around the base is an inscription referring to Gordon as a soldier, philanthropist and administrator and mentions those parts of the world in which he served, closing with a quotation from his last letter to his sisters: "I am quite happy, thank God! and, like Lawrence, I have tried to do my duty."[21] The memorial is a Grade II listed building.[22]

Gordon Lodge, close to Queen Victoria's Osborne House on the Isle of Wight, was demolished in the 1980s to be replaced by a retirement complex of the same name.

Gordon's memory, as well as his work in supervising the town's riverside fortifications, is commemorated in Gravesend; the embankment of the Riverside Leisure Area is known as the Gordon Promenade, while Khartoum Place lies just to the south. Located in the town centre of his birthplace of Woolwich is General Gordon Square, formerly known as General Gordon Place until a major urban landscaped area was developed and the road name changed. In addition, one of the first Woolwich Free Ferry vessels was named Gordon in his memory.[23]

In 1888 a statue of Gordon by Hamo Thornycroft was erected in Trafalgar Square, London, exactly halfway between the two fountains. It was removed in 1943. In a House of Commons speech on 5 May 1948, then opposition leader Winston Churchill spoke out in favour of the statue's return to its original location: "Is the right honorable Gentleman [the Minister of Works] aware that General Gordon was not only a military commander, who gave his life for his country, but, in addition, was considered very widely throughout this country as a model of a Christian hero, and that very many cherished ideals are associated with his name? Would not the right honorable Gentleman consider whether this statue [...] might not receive special consideration [...]? General Gordon was a figure outside and above the ranks of military and naval commanders." However, in 1953 the statue minus a large slice of its pedestal was reinstalled on the Victoria Embankment, in front of the newly built Ministry of Defence main buildings. An identical statue by Thornycroft—but with the pedestal intact—is located in a small park called Gordon Reserve, near Parliament House in Melbourne, Australia (a statue of the unrelated poet, Adam Lindsay Gordon, lies in the same reserve). Funded by donations from 100,000 citizens, it was unveiled in 1889.

The Corps of Royal Engineers, Gordon's own Corps, commissioned a statue of Gordon on a camel. It was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1890 and then erected in Brompton Barracks, Chatham, the home of the Royal School of Military Engineering, where it still stands. Much later a second casting was made. In 1902 it was placed at the junction of St Martin's Lane and Charing Cross Road in London. In 1904 it was moved to Khartoum, where it stood at the intersection of Gordon Avenue and Victoria Avenue, 200 meters south of the new palace that had been built in 1899. It was removed in 1958, shortly after the Sudan became independent. This is the figure which, since 1960, stands at the Gordon's School in Woking. The Royal Engineers Museum adjoining the barracks has many artifacts relating to Gordon including personal possessions. There are also memorials to Gordon in the nearby Rochester Cathedral.

A statue of General Gordon can be found in Aberdeen outside the main gates of Robert Gordon's College, a city-based independent school.

In St Paul's Cathedral, London, a slightly larger than life-size effigy of Gordon is flanked by a relief commemorating general Herbert Stewart (1843–1885), who had commanded the "flying column" of camel-borne troops, and who was mortally wounded on 19 January 1885. Stewart's grave can still be found at the Jakdul Wells in the Bayuda Desert. The commander of the Khartoum Relief Expedition 1884-1885, Sir Garnet Wolseley, lies buried beneath the effigies of Gordon and Stewart in the crypt of St Paul's.

There is a bust of Gordon in Westminster Abbey, just to the left of the main entrance when entering the building, above a doorway.

A rather fine stained-glass portrait is to be found on the main stairs of the Booloominbah building at the University of New England, in Armidale, New South Wales, Australia.

The Fairey Gordon Bomber, designed to act as part of the RAF's colonial 'aerial police force' in the Imperial territories that he helped conquer (India and North Africa), was named in his honor.

The City of Geelong, Australia, created a memorial in the form of the Gordon Technical College, which was later renamed the Gordon Institute of Technology. Part of the Institute continues under the name Gordon Institute of TAFE and the remainder was amalgamated with the Geelong State College to become Deakin University.

The suburbs of Gordon in northern Sydney and Gordon Park in northern Brisbane were named after General Gordon, as was the former Shire of Gordon in Victoria, Australia.

An elementary school in Vancouver, British Columbia, is named after General Gordon. Gordon Memorial College is a school in Khartoum. A grammar school in Medway, Kent, England, called Sir Joseph Williamson's Mathematical School, has a house named in honour of Charles George Gordon, called Gordon.

In Gloucester, there is a rugby union club called Gordon League which was formed in 1888 by Agnes Jane Waddy. The club plays in Western Counties North. The Gordon League Fishing Club uses the rugby club as its home. Gordon's Boys' Clubs were organized after General Gordon's death and the Gloucester Gordon League may be the last remaining example.

The Church Missionary Society (CMS) work in Sudan was undertaken under the name of the Gordon Memorial Mission. This was a very evangelical branch of CMS and was able to start work in Sudan in 1900 as soon as the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium took control after the fall of Khartoum in 1899. In 1885 at a meeting in London, £3,000 were allocated to a Gordon Memorial Mission in Sudan.[24]

In Khartoum, there is a small shrine to Gordon in the back of Republican Palace Museum. The museum was previously the city's largest Anglican Church, and is now dedicated primarily to gifts to Sudanese Heads of State. In the rear corner, there is a plaque commemorating those who fell with Gordon during the siege. Above is an encomium in brass letters, most of which have long since fallen off the wall leaving only silhouettes. It reads "Charles George Gordan [sic], Servant of Jesus Christ, Whose Labour Was Not in Vain with the Lord."

In the Presidential Palace in Khartoum (built in 1899), in the west wing on the ground floor, there is (or once was) a stone slab against the wall on the left side of the main corridor when coming from the main entrance with the text: "Charles George Gordon died—26 Jan 1885," on the spot where Gordon was killed, at the foot of the stairs in the old Governor-General's Palace (built around 1850).

Personality and beliefs

Gordon never married. The Rev. Reginald Barnes, who knew him well, describes him as "of the middle height, very strongly built."[25]

He was an ardent Christian cosmologist, who also believed that the Garden of Eden was on the island of Praslin in the Seychelles.[26]

Gordon believed in reincarnation. In 1877, he wrote in a letter: "This life is only one of a series of lives which our incarnated part has lived. I have little doubt of our having pre-existed; and that also in the time of our pre-existence we were actively employed. So, therefore, I believe in our active employment in a future life, and I like the thought."[27]

Media portrayals and legacy

Charlton Heston played Gordon in the 1966 epic film Khartoum, which deals with the siege of Khartoum. Laurence Olivier played Muhammad Ahmad.

Gordon's heroics have also been drawn on in the 2005 novel The Triumph of the Sun by Wilbur Smith.

The 2008 novel After Omdurman by John Ferry deals with the reconquest of the Sudan and highlights how the Anglo-Egyptian army was driven to avenge Gordon's death.

In the alternate history novel How Few Remain in which the South wins the American Civil War, Gordon, after serving in China and Sudan, raid the Montana Territory from Canada with his troops in 1882 during the Second Mexican War on behalf of Confederate allies against the Americans.

Many biographies have been written of Gordon, most of them of a highly hagiographic nature. By contrast, Gordon is one of the four subjects discussed critically in Eminent Victorians by Lytton Strachey, one of the first texts about Gordon that portrays some of his characteristics which Strachey regards as weaknesses. Notably, Strachey emphasizes the claims of Charles Chaillé-Long that Gordon was an alcoholic, an accusation dismissed by later writers like Alan Moorehead[28] and Charles Chenevix Trench.[29]

Another attempt to debunk Gordon was Anthony Nutting's Gordon, Martyr & Misfit (1966). In his Mission to Khartum—The Apotheosis of General Gordon (1969) John Marlowe portrays Gordon as "a colourful eccentric—a soldier of fortune, a skilled guerrilla leader, a religious crank, a minor philanthropist, a gadfly buzzing about on the outskirts of public life" who would have been no more than a footnote in today's history books, had it not been for "his mission to Khartoum and the manner of his death," which were elevated by the media "into a kind of contemporary Passion Play." More balanced biographies are Charley Gordon—An Eminent Victorian Reassessed (1978) by Charles Chenevix Trench and Gordon—the Man Behind the Legend (1988) by John Pollock.

In Khartoum—The Ultimate Imperial Adventure (2005), Michael Asher puts Gordon's works in the Sudan in a broad context. Asher concludes: "He did not save the country from invasion or disaster, but among the British heroes of all ages, there is perhaps no other who stands out so prominently as an individualist, a man ready to die for his principles. Here was one man among men who did not do what he was told, but what he believed to be right. In a world moving inexorably towards conformity, it would be well to remember Gordon of Khartoum."[30]

His legacy also lives on in Gordon's School, West End, near Woking in Surrey, England where the students learn about him and carry out parades. The students wear the traditional Gordon's tartan for these parades. There is also a statue there of General Gordon on a camel; in 2013 the statue was damaged and in 2014 renovation work started on it.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 "Gordon, Charles George". Dictionary of national biography 22: 169–176. 1890.

- ↑ London Gazette, Monday August 4th, 1858, No. 21909

- ↑ London Gazette, Friday May 1, 1857, No. 21996

- ↑ Ch'ing China: The Taiping Rebellion Archived 11 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 3 Platt, Part II "Order Rising"

- 1 2 3 4 5 Platt, Ch. 15

- ↑ Pollock, John (1993). Gordon: the Man behind the Legend. Lion Books. pp. 84–85.

- ↑ "Charles George Gordon (1833-1885): A Brief Biography". Victorianweb.org. 2010-06-09. Retrieved 2013-01-27.

- ↑ Slave trade in the Sudan in the nineteenth century and its suppression in the years 1877-80. Archived 3 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ MacGregor Hastie, p. 26

- ↑ "General Charles "Chinese" Gordon Reveals He is Going to Palestine". SMF Primary Source Documents. Shapell Manuscript Foundation.

- ↑ Mersh, Paul. "Charles Gordon's Charitable Works: An Appreciation".

- ↑ Cuhaj, George S., ed. (2009). Standard Catalog of World Paper Money Specialized Issues (11 ed.). Krause. pp. 1069–70. ISBN 978-1-4402-0450-0.

- ↑ Beresford, p 102–103

- 1 2 Pakenham, T. The Scramble for Africa 1876-1912, Random House (1991). p. 268

- ↑ Neufeld 1899, Appendix II, p. 332-337

- ↑ Latimer 1903

- 1 2 Pakenham, T. The Scramble for Africa 1876-1912, Random House (1991). p. 272

- 1 2 Taylor, Miles (October 2007). Southampton: Gateway to the British Empire. I.B.Tauris. pp. 83–92. ISBN 1845110323.

- ↑ "Gordon's School". Gordons.surrey.sch.uk. Retrieved 2013-01-27.

- ↑ Grant, James (1885). Cassell's history of the war in the Soudan. Cassell. p. 146. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- ↑ "Monument to General Gordon". The National Heritage List. English Heritage. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- ↑ Rogers, Robert. "Woolwich Ferry". The Newham Story. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ↑ The Sudan under Wingate: administration in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, 1899-1916 by Gabriel Warburg

- ↑ Barnes (1885) p. 1

- ↑ Linda Colley, Ghosts of Empire by Kwasi Kwarteng - review, The Guardian, 2 September 2011. Accessed 3 September 2011.

- ↑ Trench (1978) p. 128

- ↑ The White Nile, p. 179

- ↑ Charley Gordon-An Eminent Victorian Reassessed, p. 95

- ↑ Asher (2005), p. 413

References

- Allen, Bernard M. "How Khartoum Fell," Journal of the Royal African Society, Vol. 40, No. 161 (Oct., 1941), pp. 327–334.

- Asher, Michael. Khartoum—The Ultimate Imperial Adventure, (2005), 450 pp.

- Barnes, Reginald. Charles George Gordon—A Sketch, London: Macmillan & Co. (1885), 104 pp., available online

- Beresford, John. Storm and Peace, London: Cobden-Sanderson [1936] (1977), 269 pp.

- Charles George Gordon. Reflections in Palestine. London: Macmillan & Co. (1884).

- Churchill, Winston, Sir. The River War, New York: Carroll & Graf [1899]; Partridge Green: Biblios (2000), ISBN 0-7867-0751-8

- Faught, C. Brad. Gordon: Victorian Hero, Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books (2008), ISBN 978-1-59797-144-7

- Hill, George Birkbeck, ed. Colonel Gordon in Central Africa, 1874-1879] London: Thomas De La Rue and Co. (1881).

- Latimer, E.W. "Gordon and the Mahdi," in Europe in Africa in the Nineteenth Century, 4th Ed. A.C. McClurg, Chicago (1895, 1903).

- MacGregor-Hastie, Roy. Never to be Taken Alive—A Biography of General Gordon, (1985) ISBN 0-283-99184-4

- Neufeld, Charles. A Prisoner of the Khaleefa], London: Chapman & Hall (1899).

- Platt, Stephen R. Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom: China, the West, and the Epic Story of the Taiping Civil War, Knopf (2012), ISBN 978-0-307-95759-7

- Pollock, John. Gordon : the Man Behind the Legend, London: Constable (1993), ISBN 0-09-468560-6

- Smith, George Barnett. General Gordon The Christian Soldier and Hero, London: S.W. Partridge & Co. (1896), 160 pp.

- Strachey, G. Lytton. Eminent Victorians, Illustrated Ed., London: Bloomsbury [1918] (1988). ISBN 0-7475-0218-8, available online at http://www.bartleby.com/189/401.html

- Trench, Charles Chenevix. Charley Gordon, An Eminent Victorian Reassessed, London: Allan Lane [1978], 320 pp. ISBN 0-7139-0895-5,

- Wortham, Hugh Evelyn. Gordon : An Intimate Portrait, London: Harrap (1933), 342 pp.

- White, Adam. Hamo Thornycroft & the Martyr General, Leeds: The Henry Moore Centre for the Study of Sculpture (1991), 72 pp.

- Moorehead, Alan. The White Nile, London: Hamish Hamilton, (1960, rev. 1971), 366 pp.

- Gillmeister, Heiner. "The Maloja Mystery, or the Case of the Living Pictures," in ACD-The Journal of The Arthur Conan Doyle Society, Vol. 7 (1996/7), pp. 53–69.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles George Gordon. |

- Original Letters Written by Charles Gordon from the Near East Shapell Manuscript Foundation

- Chinese Gordon on the Soudan Gordon's famous interview to the Pall Mall Gazette, 1884

- Gordon's tactics: an alternative view analysis of Gordon's war strategy by Gary Brecher (the War Nerd)

- Charles G. Gordon Photograph part of the Nineteenth Century Notables Digital Collection at Gettysburg College

- The Journals of Major-Gen. C. G. Gordon, C.B., at Kartoum Project Gutenberg

| Government offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Abdallahi ibn Muhammad as Mahdi of Sudan |

Interim Governor-General of the Sudan 1880-1885 |

Succeeded by Mahdist State |

|

.jpg)