Old Swiss Confederacy

| Republic of the Swiss | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eidgenossenschaft République des Suisses Republica Helvetiorum | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

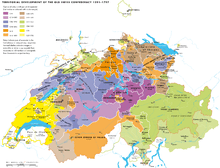

The Old Swiss Confederacy in the 18th century | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | see Vorort[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | Middle French / French, Alemannic German, Lombard, Rhaeto-Romansh | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political structure | Confederation | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Tagsatzung | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | Death of Rudolf I | 15 July 1291 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | Rütlischwur, Burgenbruch | 1307/1291 (traditional dates) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | Charles IV's Golden Bull | 1356 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | Battle of Marignano | 13–14 September 1515 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | Wars of Kappel | 1529 and 1531 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | Formal independence from the HRE | 15 May/24 October 1648 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | Swiss peasant war | January–June 1653 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | Collapse | 5 March 1798 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Switzerland |

.svg.png) |

| Early history |

| Old Swiss Confederacy |

|

| Transitional period |

|

| Modern history |

|

| Timeline |

| Topical |

| Switzerland portal |

The Old Swiss Confederacy (Modern German: Alte Eidgenossenschaft; historically Eidgenossenschaft, after the Reformation République des Suisses, Republica Helvetiorum "Republic of the Swiss") was a precursor of the modern state of Switzerland.

It was a loose confederation of independent small states (lieus, later cantons) which formed during the 14th century. From a nucleus in what is now Central Switzerland, the confederacy expanded to include the cities of Zurich and Berne by the middle of the century. This formed a rare union of rural and urban communes, all of which enjoyed imperial immediacy in the Holy Roman Empire.

This confederation of eight lieus (Acht Orte) was politically and militarily successful for more than a century, culminating in the Burgundy Wars of the 1470s which established it as a power in the complicated political landscape dominated by France and the Habsburgs. Its success resulted in the addition of more confederates, increasing the number of lieus to thirteen (Dreizehn Orte) by 1513. The confederacy pledged neutrality in 1515 and 1647 (under the threat of the Thirty Years' War), although many Swiss served privately as mercenaries in the Italian Wars and during the Early Modern period.

After the Swabian War of 1499 the confederacy was a de facto independent state throughout the early modern period, although still nominally part of the Holy Roman Empire until 1648. The Swiss Reformation divided the confederates into Reformed and Catholic parties, resulting in internal conflict from the 16th to the 18th centuries; as a result, the federal diet (Tagsatzung) was often paralysed by hostility between the factions. The Swiss Confederacy fell to invasion by the French Revolutionary Army in 1798, after which it became the short-lived Helvetic Republic.

Name

The adjective “old” was introduced after the Napoleonic era with Ancien Régime, retronyms distinguishing the pre-Napoleonic from the restored confederation. During its existence the confederacy was known as Eidgenossenschaft or Eydtgnoschafft ("oath fellowship"), in reference to treaties among cantons; this term was first used in the 1370 Pfaffenbrief. Territories of the confederacy came to be known collectively as Schweiz or Schweizerland (Schwytzerland in contemporary spelling), with the English Switzerland beginning during the mid-16th century. From that time the Confederacy was seen as a single state, also known as the Swiss Republic (Republic der Schweitzer, République des Suisses and Republica Helvetiorum by Josias Simmler in 1576) after the fashion of calling individual urban cantons republics (such as the Republics of Zürich, Berne and Basel).

History

Foundation

The nucleus of the Old Swiss Confederacy was an alliance among the valley communities of the central Alps to facilitate management of common interests (such as trade) and ensure peace along trade routes through the mountains. The foundation of the Confederacy is marked by the Rütlischwur (dated to 1307 by Aegidius Tschudi) or the 1315 Pact of Brunnen. Since 1889, the Federal Charter of 1291 among the rural communes of Uri, Schwyz, and Unterwalden has been considered the founding document of the confederacy.[2]

Federation growth

The initial pact was augmented by pacts with the cities of Lucerne, Zürich, and Berne. This union of rural and urban communes, which enjoyed the status of imperial immediacy within the Holy Roman Empire, was engendered by pressure from Habsburg dukes and kings who had ruled much of the land. In several battles with Habsburg armies, the Swiss were victorious; they conquered the rural areas of Glarus and Zug, which became members of the confederacy.[2]

From 1353 to 1481, the federation of eight cantons—known in German as the Acht Orte (Eight Lieus)—consolidated its position. The members (especially the cities) enlarged their territory at the expense of local counts—primarily by buying judicial rights, but sometimes by force. The Eidgenossenschaft, as a whole, expanded through military conquest: the Aargau was conquered in 1415 and the Thurgau in 1460. In both cases, the Swiss profited from weakness in the Habsburg dukes. In the south, Uri led a military territorial expansion that (after many setbacks) would by 1515 lead to the conquest of the Ticino. None of these territories became members of the confederacy; they had the status of condominiums (regions administered by several cantons).

At this time, the eight cantons gradually increased their influence on neighbouring cities and regions through additional alliances. Individual cantons concluded pacts with Fribourg, Appenzell, Schaffhausen, the abbot and the city of St. Gallen, Biel, Rottweil, Mulhouse and others. These allies (known as the Zugewandte Orte) became closely associated with the confederacy, but were not accepted as full members.

The Burgundy Wars prompted a further enlargement of the confederacy; Fribourg and Solothurn were accepted in 1481. In the Swabian War against Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, the Swiss were victorious and exempted from imperial legislation. The associated cities of Basel and Schaffhausen joined the confederacy as a result of that conflict, and Appenzell followed suit in 1513 as the thirteenth member. The federation of thirteen cantons (Dreizehn Orte) constituted the Old Swiss Confederacy until its demise in 1798.

The expansion of the confederacy was stopped by the Swiss defeat in the 1515 Battle of Marignano. Only Berne and Fribourg were still able to conquer the Vaud in 1536; the latter primarily became part of the canton of Berne, with a small portion under the jurisdiction of Fribourg.

Reformation

The Reformation in Switzerland led to doctrinal division amongst the cantons.[2] Zürich, Berne, Basel, Schaffhausen and associates Biel, Mulhouse, Neuchâtel, Geneva and the city of St. Gallen became Protestant; other members of the confederation and the Valais remained Catholic. In Glarus, Appenzell, in the Grisons and in most condominiums both religions coexisted; Appenzell split in 1597 into a Catholic Appenzell Inner Rhodes and a Protestant Appenzell Outer Rhodes.

The division led to civil war (the Wars of Kappel) and separate alliances with foreign powers by the Catholic and Protestant factions, but the confederacy as a whole continued to exist. A common foreign policy was blocked, however, by the impasse. During the Thirty Years' War, religious disagreements among the cantons kept the confederacy neutral and spared it from belligerents. At the Peace of Westphalia, the Swiss delegation was granted formal recognition of the confederacy as a state independent of the Holy Roman Empire.

Early modern period

Growing social differences and an increasing absolutism in the city cantons during the Ancien Régime led to local popular revolts. An uprising during the post-war depression after the Thirty Years' War escalated to the Swiss peasant war of 1653 in Lucerne, Berne, Basel, Solothurn and the Aargau. The revolt was put down by force with the aid of other cantons.

Religious differences were accentuated by a growing economic discrepancy. The Catholic, predominantly rural central-Swiss cantons were surrounded by Protestant cantons with increasingly commercial economies. The politically dominant cantons were Zürich and Berne (both Protestant), but the Catholic cantons were influential since the Second War of Kappel in 1531. A 1655 attempt (led by Zürich) to restructure the federation was blocked by Catholic opposition, which led to the first battle of Villmergen in 1656; the Catholic party won, cementing the status quo. The problems remained unsolved, erupting again in 1712 with the second battle of Villmergen. This time the Protestant cantons won, dominating the confederation. True reform, however, was impossible; the individual interests of the thirteen members were too diverse, and the absolutist cantonal governments resisted all attempts at confederation-wide administration. Foreign policy remained fragmented.

Collapse

Attempting to gain control of key Alpine passes and establish a buffer against hostile monarchies, France first invaded associates of the Swiss Confederation; part of the bishopric of Basel was absorbed by France in 1793. In 1797, Napoleon annexed the Valtellina (on the border with Graubünden) into the new Cisalpine Republic in northern Italy and invaded the southern remainder of the bishopric of Basel.[3][4]

In 1798 the confederacy was invaded by the French Revolutionary Army at the invitation of the Republican faction in Vaud, led by Frédéric-César de La Harpe. Vaud was under Bernese control, but chafed under a government with a different language and culture. The ideals of the French Revolution found a receptive audience in Vaud, and when Vaud declared itself a republic the French had a pretext to invade the confederation.

The invasion was largely peaceful (since the Swiss people failed to respond to political calls to take up arms), and the collapse of the confederacy was due more to internal strife than external pressure. Only Bern put up an effective resistance, but after its defeat in the March Battle of Grauholz it capitulated. The canton of Bern was divided into the canton of Oberland (with Thun as its capital) and the canton of Léman (with Lausanne as its capital).

The Helvetic Republic was proclaimed on 12 April 1798 as "one and indivisible", abolishing cantonal sovereignty and feudal rights and reducing the cantons to administrative districts. This system was unstable due to widespread opposition, and the Helvetic Republic collapsed as a result of the Stecklikrieg. A federalist compromise solution was attempted, but conflict between the federalist elite and republican subjects persisted until the formation of the federal state in 1848.

Structure

The (Alte) Eidgenossenschaft was initially united not by a single pact, but by overlapping pacts and bilateral treaties between members.[5] The parties generally agreed to preserve the peace, aid in military endeavours and arbitrate disputes. Slowly, the members began to see the confederation as a unifying entity. In the Pfaffenbrief, a treaty of 1370 among six of the eight members (Glarus and Berne did not participate) forbidding feuds and denying clerical courts jurisdiction over the confederacy, the cantons for the first time used the term Eidgenossenschaft. The first treaty uniting the eight members of the confederacy was the Sempacherbrief of 1393, concluded after victories over the Habsburgs at Sempach in 1386 and Näfels in 1388, which forbade a member from unilaterally beginning a war without the consent of the other cantons. A federal diet, the Tagsatzung, developed during the 15th century.

Pacts and renewals (or modernizations) of earlier alliances reinforced the confederacy. The individual interests of the cantons clashed in the Old Zürich War (1436–1450), caused by territorial conflict among Zürich and the central Swiss cantons over the succession of the Count of Toggenburg. Although Zürich entered an alliance with the Habsburg dukes, it then rejoined the confederacy. The confederation had become so close a political alliance that it no longer tolerated separatist tendencies in its members.

The Tagsatzung was the confederation council, typically meeting several times a year. Each canton delegated two representatives (including the associate states, which had no vote). The canton where the delegates met initially chaired the gathering, but during the 16th century Zürich permanently assumed the chair (Vorort) and Baden became the seat. The Tagsatzung dealt with inter-cantonal affairs and was the court of last resort in disputes between member states, imposing sanctions on dissenting members. It also administered the condominiums; the reeves were delegated for two years, each time by a different canton.[6]

A unifying treaty of the Old Swiss Confederacy was the Stanser Verkommnis of 1481. Conflicts between rural and urban cantons and disagreements over the bounty of the Burgundian Wars had led to skirmishes. The city-states of Fribourg and Solothurn wanted to join the confederacy, but were distrusted by the central Swiss rural cantons. The compromise by the Tagsatzung in the Stanser Verkommnis restored order and assuaged the rural cantons' complaints, with Fribourg and Solothurn accepted into the confederation. While the treaty restricted freedom of assembly (many skirmishes arose from unauthorised expeditions by soldiers from the Burgundian Wars), it reinforced agreements amongst the cantons in the earlier Sempacherbrief and Pfaffenbrief.

The civil war during the Reformation ended in a stalemate. The Catholic cantons could block council decisions but, due to geographic and economic factors, could not prevail over the Protestant cantons. Both factions began to hold separate councils, still meeting at a common Tagsatzung (although the common council was deadlocked by disagreements between both factions until 1712, when the Protestant cantons gained power after their victory in the second war of Villmergen). The Catholic cantons were excluded from administering the condominiums in the Aargau, the Thurgau and the Rhine valley; in their place, Berne became co-sovereign of these regions.

Territories

Cantons

The confederation expanded in several stages: first to the Eight Cantons (Acht Orte), in 1481 to ten, in 1501 to twelve and finally to thirteen cantons (Dreizehn Orte).[7] The founding cantons (Urkantone) were:

- Uri, founding canton named in the Federal Charter of 1291

- Schwyz, founding canton named in the Federal Charter of 1291

- Unterwalden, founding canton named in the Federal Charter of 1291

The 14th century saw expansion to the Achtörtige Eidgenossenschaft following the battles of Morgarten and Laupen:

- Lucerne, city canton since 1332

- Zürich, city canton since 1351

- Glarus, rural canton since 1352

- Zug, city canton since 1352

- Berne, city canton since 1353 (associate since 1323)

The 15th century was marked by expansion to the Zehnörtige Eidgenossenschaft after the Burgundian Wars:

- Fribourg, city canton since 1481 (associate since 1454)

- Solothurn, city canton since 1481 (associate since 1353)

The 16th-century expansion to the Dreizehnörtige Eidgenossenschaft followed the Swabian War:

- Basel, city canton since 1501

- Schaffhausen, city canton since 1501 (associate since 1454)

- Appenzell, rural canton since 1513 (associate since 1411)

Associates

Associates (Zugewandte Orte) were close allies of the Old Swiss Confederacy, connected to the union by treaties with all (or some) of the members of the confederacy.

Close associates

Three of the associates were known as Engere Zugewandte:

- Biel – 1344–82 treaties with Fribourg, Berne and Solothurn. Nominally, Biel was subject to the Bishopric of Basel.

- Imperial Abbey of St. Gallen – 1451 treaty with Schwyz, Lucerne, Zürich and Glarus, renewed in 1479 and 1490 (also a protectorate)

- Imperial City of St. Gallen – 1454 treaty with Schwyz, Lucerne, Zürich, Glarus, Zug and Berne

Eternal associates

Two federations were known as Ewige Mitverbündete:

- Sieben Zenden, an independent federation in the Valais – Became a Zugewandter Ort in 1416 through an alliance with Uri, Unterwalden and Lucerne, followed by a treaty with Berne in 1446.

- The Three Leagues were independent federations in the Grisons which became associated with the Old Swiss Confederacy in 1497–98 with the Swabian War. The Three Leagues concluded an alliance with Berne in 1602.

- The Grey League (which was allied with Glarus, Uri and Obwalden by pacts in 1400, 1407 and 1419) entered an alliance with seven of the old eight cantons (the Acht Orte, excluding Berne) in 1497.

- The League of God's House (Gotteshausbund) followed suit a year later.

- The League of the Ten Jurisdictions, the third of the leagues, entered an alliance with Zürich and Glarus in 1590.

Protestant associates

There were two Evangelische Zugewandte:

- Imperial City of Mulhouse – Concluded a treaty with several cantons in 1466; became an associate in 1515 through a treaty with all 13 members of the Confederacy, remaining so until the French Revolutionary Wars in 1797.

- Imperial City of Geneva – 1536 treaty with Berne and 1584 treaty with Zürich and Berne

Remaining associates

- County of Neuchâtel – 1406 and 1526 treaties with Berne and Solothurn, 1495 treaty with Fribourg and 1501 treaty with Lucerne

- Imperial Valley of Urseren – 1317 treaty with Uri; annexed by Uri in 1410.

- Weggis – 1332–1380 by treaties with Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden and Lucerne; annexed by Lucerne in 1480.

- Murten – 1353 treaty with Berne; became a confederal condominium in 1475.

- Payerne – 1353 treaty with Berne; annexed by Berne in 1536.

- Vogtei of Bellinzona – 1407 treaty with Uri and Obwalden; became confederal condominium in 1419–22.

- County of Sargans – 1437 treaty with Glarus and Schwyz; became confederal condominium in 1483.

- Barony of Sax-Forstegg – 1458 treaty with Zürich; annexed by Zürich in 1615.

- Stein am Rhein – 1459 by treaty with Zürich and Schaffhausen; annexed by Zürich in 1484.

- County of Gruyère – allied with Fribourg and Berne since the early 14th century; became full associate of the Confederation in 1548. When the counts fell into bankruptcy in 1555, the county was partitioned into:[8]

- Lower Gruyère – 1475 treaty with Fribourg

- Upper Gruyère – 1403 treaty with Berne; annexed by Berne in 1555:

- County of Werdenberg – 1493 treaty with Lucerne; annexed by Glarus in 1517.

- Imperial City of Rottweil – 1519–1632 through treaties with all 13 members; a first treaty (on military cooperation) had been concluded in 1463. In 1632 the treaty was renewed with Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden, Zug, Solothurn and Fribourg.

- Bishopric of Basel – 1579–1735 by treaty with Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden, Zug, Solothurn and Fribourg

Condominiums

Condominiums (German: Gemeine Herrschaften) were territories under the administration of several cantons. They were governed by reeves (Vögte) delegated for two years, each time from a different responsible canton. Berne initially did not participate in the administration of some of the eastern condominiums, since it had no part in their conquest and its interests were focused on the western border. In 1712 Berne replaced the Catholic cantons in the administration of the Freie Ämter (Free Districts), the Thurgau, the Rhine valley, and Sargans, and the Catholic cantons were excluded from administering of the County of Baden.[5]

German territories

The German territories (German: Deutsche Gemeine Vogteien, Gemeine Herrschaften) were generally governed by the Acht Orte (apart from Bern) until 1712, when Bern joined the sovereign powers:

- Freie Ämter – conquered in 1415; partitioned in 1712 into:

- Upper Freiamt, governed by the Acht Orte

- Lower Freiamt, governed by Zürich, Bern and Glarus

- County of Baden – conquered 1415; after 1712 governed by Zürich, Bern and Glarus

- County of Sargans – 1460–83

- Landgraviate of Thurgau – 1460

- Vogtei of Rheintal – 1490 by the Acht Orte (except Bern), with the Imperial Abbey of St Gall. Appenzell added in 1500; Bern added in 1712.

Italian territories

Several territories (Vogteien) were known as "transmontane territories" (German: Ennetbergische Vogteien, Italian: Baliaggi Ultramontani). In 1440, Uri conquered the Leventina Valley from the Visconti (dukes of Milan). Some of this territory had previously been annexed between 1403 and 1422. Further territories were acquired in 1500.

Three territories, all now in the Ticino, were condominiums of the forest cantons of Uri, Schwyz and Nidwalden:

- Vogtei of Blenio – 1477–80 and after 1495

- Vogtei of Rivera – 1403–22 and after 1495

- Vogtei of Bellinzona – after 1500

Four other Ticinese territories were condominiums of the Zwölf Orte (the original 13 cantons, minus Appenzell) after 1512:

Another three territories were condominiums of the Zwölf Orte after 1512, but were lost from the confederacy three years later and are now comuni of Lombardy and Piedmont:

- Travaglia

- Cuvio

- Eschental (now Ossola)

Two-party condominiums

Vogteien of Bern and Fribourg

- County of Grasburg-Schwarzenburg – after 1423

- Murten – after 1475

- Grandson – after 1475

- Orbe and Echallens – after 1475

Vogteien of Glarus and Schwyz

- County of Uznach – 1437

- Lordship of Windegg-Gaster – 1438

- Lordship of Hohensax-Gams – 1497

Third-party condominium

- Shire of Tessenberg – 1388 (between Bern and the Bishopric of Basel)

Protectorates

- Bellelay Abbey – protectorate of Bern, Biel and Solothurn after 1414; nominally under the jurisdiction of the Bishopric of Basel

- Einsiedeln Abbey – protectorate of Schwyz after 1357

- Engelberg Abbey – protectorate of Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz and Unterwalden after 1425

- Erguel – protectorate of Biel/Bienne under military jurisdiction after 1335; also subject to the Bishopric of Basel

- Imperial Abbey of St. Gallen – protectorate of Schwyz, Lucerne, Zürich and Glarus after 1451 (also a Zugewandter Ort)

- Republic of Gersau, an independent village – allied with Schwyz after 1332; Lucerne, Uri and Unterwalden were also protecting powers.

- Moutier-Grandval Abbey – protectorate of Bern after 1486; also subject to the Bishopric of Basel and (until 1797) the Holy Roman Empire

- La Neuveville – protectorate of Bern after 1388; also subject to the Bishopric of Basel

- Pfäfers Abbey – protectorate of the Acht Orte (minus Berne) after 1460; annexed to County of Sargans 1483

- Rapperswil – protectorate of Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden and Glarus after 1464, of Zürich, Berne and Glarus after 1712

- County of Toggenburg – protectorate of Schwyz and Glarus after 1436, and of Zürich and Bern after 1718; also subject to St. Gallen Abbey

Separate subjects

Some territories were subjects of the following cantons or associates (German: Einzelörtische Untertanen von Länderorten und Zugewandten):

Uri

Schwyz

- Küssnacht (1402)

- Einsiedeln Abbey (1397–1424)

- March (1405–36)

- Höfe (1440)

Glarus

- County of Werdenberg (1485–1517); annexed by Lucerne 1485, by Glarus 1517

Republic of Valais

- St-Maurice (1475–77)

- Monthey (1536)

- Nendaz-Hérémence (1475–77)

- Port Valais-Vionnaz

- Lötschental (15th century): the five upper Zenden

Three Leagues

- Bormio (1512)

- Chiavenna (1512)

- Valtellina (1512)

- Drei Pleven (1512–26)

- Maienfeld (Bündner Herrschaft) (1509–1790); also member of the League of the Ten Jurisdictions

Notes and references

- ↑ the Swiss diet was presided de facto by Zurich during most of the 15th century. After the Reformation in Switzerland, the system of administration became more multipolar, with Lucerne and Berne playing an important role besides Zürich.Vorort in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- 1 2 3 Schwabe & Co.: Geschichte der Schweiz und der Schweizer, Schwabe & Co 1986/2004. ISBN 3-7965-2067-7 (German)

- ↑ Swissworld.org accessed 1 February 2013

- ↑ French Invasion in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- 1 2 Würgler, A.: Eidgenossenschaft in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland, 8 September 2004.

- ↑ Im Hof, U.. Geschichte der Schweiz, 7th ed., Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer, 1974/2001. ISBN 3-17-017051-1. (German)

- ↑ Boschetti-Maradi, A.: County of Gruyère in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland, 28 June 2004.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alte Eidgenossenschaft. |

- Aubert, J.-F.: Petite histoire constitutionnelle de la Suisse, 2nd ed.; Francke Editions, Bern, 1974. (French)

- Peyer, H.C.: Verfassungsgeschichte der alten Schweiz, Schulthess Polygraphischer Verlag, Zürich 1978. ISBN 3-7255-1880-7. (German)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||