Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (Middle English: Sir Gawayn and þe Grene Knyȝt) is a late 14th-century Middle English chivalric romance. It is one of the best known Arthurian stories, with its plot combining two types of folklore motifs, the beheading game and the exchange of winnings. The Green Knight is interpreted by some as a representation of the Green Man of folklore and by others as an allusion to Christ. Written in stanzas of alliterative verse, each of which ends in a rhyming bob and wheel,[1] it draws on Welsh, Irish and English stories, as well as the French chivalric tradition. It is an important poem in the romance genre, which typically involves a hero who goes on a quest which tests his prowess, and it remains popular to this day in modern English renderings from J. R. R. Tolkien, Simon Armitage and others, as well as through film and stage adaptations.

It describes how Sir Gawain, a knight of King Arthur's Round Table, accepts a challenge from a mysterious "Green Knight" who challenges any knight to strike him with his axe if he will take a return blow in a year and a day. Gawain accepts and beheads him with his blow, at which the Green Knight stands up, picks up his head and reminds Gawain of the appointed time. In his struggles to keep his bargain Gawain demonstrates chivalry and loyalty until his honour is called into question by a test involving Lady Bertilak, the lady of the Green Knight's castle.

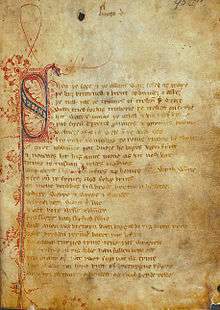

The poem survives in a single manuscript, the Cotton Nero A.x., which also includes three religious narrative poems: Pearl, Purity and Patience. All are thought to have been written by the same unknown author, dubbed the "Pearl Poet" or "Gawain Poet", since all four are written in a North West Midland dialect of Middle English.[2][3]

Synopsis

In Camelot on New Year's Day, King Arthur's court is exchanging gifts and waiting for the feasting to start when the king asks first to see or hear of an exciting adventure. At this a gigantic figure, entirely green in appearance and riding a green horse, rides unexpectedly into the hall. He wears no armour but bears an axe in one hand and a holly bough in the other. Refusing to fight anyone there on the grounds that they are all too weak to take him on, he insists he has come for a friendly "Christmas game": someone is to strike him once with his axe on condition that the Green Knight may return the blow in a year and a day.[4] The splendid axe will belong to whomever takes him on. Arthur himself is prepared to accept the challenge when it appears no other knight will dare, but Sir Gawain, youngest of Arthur's knights and his nephew, begs for the honour instead. The giant bends and bares his neck before him and Gawain neatly beheads him in one stroke. However, the Green Knight neither falls nor falters, but instead reaches out, picks up his severed head and remounts, holding up his bleeding head to Queen Guinevere while its writhing lips remind Gawain that the two must meet again at the Green Chapel. He then rides away. Gawain and Arthur admire the axe, hang it up as a trophy and encourage Guinevere to treat the whole matter lightly.

As the date approaches, Sir Gawain sets off to find the Green Chapel and keep his side of the bargain. Many adventures and battles are alluded to (but not described) until Gawain comes across a splendid castle where he meets Bertilak de Hautdesert, the lord of the castle, and his beautiful wife, who are pleased to have such a renowned guest. Also present is an old and ugly lady, unnamed but treated with great honour by all. Gawain tells them of his New Year's appointment at the Green Chapel and that he only has a few days remaining. Bertilak laughs, explains that the Green Chapel is less than two miles away and proposes that Gawain rest at the castle till then. Relieved and grateful, Gawain agrees.

Before going hunting the next day Bertilak proposes a bargain: he will give Gawain whatever he catches on the condition that Gawain give him whatever he might gain during the day. Gawain accepts. After Bertilak leaves, Lady Bertilak visits Gawain's bedroom and behaves seductively, but despite her best efforts he yields nothing but a single kiss in his unwillingness to offend her. When Bertilak returns and gives Gawain the deer he has killed, his guest gives a kiss to Bertilak without divulging its source. The next day the lady comes again, Gawain again courteously foils her advances, and later that day there is a similar exchange of a hunted boar for two kisses. She comes once more on the third morning, this time offering Gawain a gold ring as a keepsake. He gently but steadfastly refuses but she pleads that he at least take her belt, a girdle of green and gold silk which, the lady assures him, is charmed and will keep him from all physical harm. Tempted, as he may otherwise die the next day, Gawain accepts it, and they exchange three kisses. That evening, Bertilak returns with a fox, which he exchanges with Gawain for the three kisses – but Gawain says nothing of the girdle.

The next day, Gawain leaves for the Green Chapel with the girdle wound twice around his waist. He finds the Green Knight sharpening an axe and, as promised, Gawain bends his bared neck to receive his blow. At the first swing Gawain flinches slightly and the Green Knight belittles him for it. Ashamed of himself, at the Green Knight's next swing Gawain does not flinch; but again the full force of the blow is withheld. The knight explains he was testing Gawain's nerve. Angrily Gawain tells him to deliver his blow and so the knight does, causing only a slight wound on Gawain's neck. The game is over. Gawain seizes his sword, helmet and shield, but the Green Knight, laughing, reveals himself to be the lord of the castle, Bertilak de Hautdesert, transformed by magic. He explains that the entire adventure was a trick of the 'elderly lady' Gawain saw at the castle, who is actually the sorceress Morgan le Fay, Arthur's sister, who intended to test Arthur's knights and frighten Guinevere to death.[5] Gawain is ashamed to have behaved deceitfully but the Green Knight laughs at his scruples and the two part on cordial terms. Gawain returns to Camelot wearing the girdle as a token of his failure to keep his promise. The Knights of the Round Table absolve him of blame and decide that henceforth that they will wear a green sash in recognition of Gawain's adventure.

"Pearl Poet"

Though the real name of "The Gawain Poet" (or poets) is unknown, some inferences about him or her can be drawn from an informed reading of his or her works. The manuscript of Gawain is known in academic circles as Cotton Nero A.x., following a naming system used by one of its owners, Robert Cotton, a collector of Medieval English texts.[3] Before the Gawain manuscript came into Cotton's possession, it was in the library of Henry Savile of Bank in Yorkshire.[6] Little is known about its previous ownership, and until 1824, when the manuscript was introduced to the academic community in a second edition of Thomas Warton's History edited by Richard Price, it was almost entirely unknown. Even then, the Gawain poem was not published in its entirety until 1839.[7][8] Now held in the British Library, it has been dated to the late 14th century, meaning the poet was a contemporary of Geoffrey Chaucer, author of The Canterbury Tales, though it is unlikely that they ever met.[9] The three other works found in the same manuscript as Gawain (commonly known as Pearl, Patience, and Purity or Cleanliness) are often considered to be written by the same author. However, the manuscript containing these poems was transcribed by a copyist and not by the original poet. Although nothing explicitly suggests that all four poems are by the same poet, comparative analysis of dialect, verse form, and diction have pointed towards single authorship.[10]

What is known today about the poet is largely general. As J. R. R. Tolkien and E. V. Gordon, after reviewing the text's allusions, style, and themes, concluded in 1925:

He was a man of serious and devout mind, though not without humour; he had an interest in theology, and some knowledge of it, though an amateur knowledge perhaps, rather than a professional; he had Latin and French and was well enough read in French books, both romantic and instructive; but his home was in the West Midlands of England; so much his language shows, and his metre, and his scenery.[11]

The most commonly suggested candidate for authorship is John Massey of Cotton, Cheshire.[12] He is known to have lived in the dialect region of the Pearl Poet and is thought to have written the poem St. Erkenwald, which some scholars argue bears stylistic similarities to Gawain. St. Erkenwald, however, has been dated by some scholars to a time outside the Gawain poet's era. Thus, ascribing authorship to John Massey is still controversial and most critics consider the Gawain poet an unknown.[10]

Verse form

The 2,530 lines and 101 stanzas that make up Sir Gawain and the Green Knight are written in what linguists call the "Alliterative Revival" style typical of the 14th century. Instead of focusing on a metrical syllabic count and rhyme, the alliterative form of this period usually relied on the agreement of a pair of stressed syllables at the beginning of the line and another pair at the end. Each line always includes a pause, called a caesura, at some point after the first two stresses, dividing it into two half-lines. Although he largely follows the form of his day, the Gawain poet was somewhat freer with convention than his or her predecessors. The poet broke the alliterative lines into variable-length groups and ended these nominal stanzas with a rhyming section of five lines known as the bob and wheel, in which the "bob" is a very short line, sometimes of only two syllables, followed by the "wheel," longer lines with internal rhyme.[2]

| Gawain | Translation | |

|---|---|---|

| (bob) ful clene |

(bob) |

Similar stories

The earliest known story to feature a beheading game is the 8th-century Middle Irish tale Bricriu's Feast. This story parallels Gawain in that, like the Green Knight, Cú Chulainn's antagonist feints three blows with the axe before letting his target depart without injury. A beheading exchange also appears in the late 12th-century Life of Caradoc, a Middle French narrative embedded in the anonymous First Continuation of Chrétien de Troyes' Perceval, the Story of the Grail. A notable difference in this story is that Caradoc's challenger is his father in disguise, come to test his honour. Lancelot is given a beheading challenge in the early 13th-century Perlesvaus, in which a knight begs him to chop off his head or else put his own in jeopardy. Lancelot reluctantly cuts it off, agreeing to come to the same place in a year to put his head in the same danger. When Lancelot arrives, the people of the town celebrate and announce that they have finally found a true knight, because many others had failed this test of chivalry.[14]

The stories The Girl with the Mule (alternately titled The Mule Without a Bridle) and Hunbaut feature Gawain in beheading game situations. In Hunbaut, Gawain cuts off a man's head and, before he can replace it, removes the magic cloak keeping the man alive, thus killing him. Several stories tell of knights who struggle to stave off the advances of voluptuous women sent by their lords as a test; these stories include Yder, the Lancelot-Grail, Hunbaut, and The Knight of the Sword. The last two involve Gawain specifically. Usually the temptress is the daughter or wife of a lord to whom the knight owes respect, and the knight is tested to see whether or not he will remain chaste in trying circumstances.[14]

In the first branch of the medieval Welsh collection of tales known as the Mabinogion, Pwyll exchanges places for a year with Arawn, the lord of Annwn (the Otherworld). Despite having his appearance changed to resemble Arawn exactly, Pwyll does not have sexual relations with Arawn's wife during this time, thus establishing a lasting friendship between the two men. This story may, then, provide a background Gawain's attempts to resist to the wife of the Green Knight; thus, the story of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight may be seen as a tale which combines elements of the Celtic beheading game and seduction test stories. Additionally, in both stories a year passes before the completion of the conclusion of the challenge or exchange is complete. Some scholars disagree with this interpretation, however, as Arawn seems to have accepted the notion that Pwyll may reciprocate with his wife, making it less of a "seduction test" per se, as seduction tests typically involve a Lord and Lady conspiring to seduce a knight, seemingly against the wishes of the Lord.[15]

After the writing of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, several similar stories followed. The Greene Knight (15th–17th century) is a rhymed retelling of nearly the same tale.[16] In it, the plot is simplified, motives are more fully explained, and some names are changed. Another story, The Turke and Gowin (15th century), begins with a Turk entering Arthur's court and asking, "Is there any will, as a brother, To give a buffett and take another?"[17] At the end of this poem the Turk, rather than buffeting Gawain back, asks the knight to cut off his head, which Gawain does. The Turk then praises Gawain and showers him with gifts. The Carle of Carlisle (17th century) also resembles Gawain in a scene in which the Carle (Churl), a lord, takes Sir Gawain to a chamber where two swords are hanging and orders Gawain to cut off his head or suffer his own to be cut off.[18] Gawain obliges and strikes, but the Carle rises, laughing and unharmed. Unlike the Gawain poem, no return blow is demanded or given.[14][15]

Themes

Temptation and testing

At the heart of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is the test of Gawain's adherence to the code of chivalry. The typical temptation fable of medieval literature presents a series of tribulations assembled as tests or "proofs" of moral virtue. The stories often describe several individuals' failures after which the main character is tested.[19] Success in the proofs will often bring immunity or good fortune. Gawain's ability to pass the tests of his host are of utmost importance to his survival, though he does not know it. It is only by fortuity or "instinctive-courtesy" that Sir Gawain is able to pass his test.[20]

In addition to the laws of chivalry, Gawain must respect another set of laws concerning courtly love. The knight's code of honour requires him to do whatever a damsel asks. Gawain must accept the girdle from the Lady, but he must also keep the promise he has made to his host that he will give whatever he gains that day. Gawain chooses to keep the girdle out of fear of death, thus breaking his promise to the host but honouring the lady. Upon learning that the Green Knight is actually his host (Bertilak), he realises that although he has completed his quest, he has failed to be virtuous. This test demonstrates the conflict between honour and knightly duties. In breaking his promise, Gawain believes he has lost his honour and failed in his duties.[21]

Hunting and seduction

Scholars have frequently noted the parallels between the three hunting scenes and the three seduction scenes in Gawain. They are generally agreed that the fox chase has significant parallels to the third seduction scene, in which Gawain accepts the girdle from Bertilak's wife. Gawain, like the fox, fears for his life and is looking for a way to avoid death from the Green Knight's axe. Like his counterpart, he resorts to trickery in order to save his skin. The fox uses tactics so unlike the first two animals, and so unexpectedly, that Bertilak has the hardest time hunting it. Similarly, Gawain finds the Lady's advances in the third seduction scene more unpredictable and challenging to resist than her previous attempts. She changes her evasive language, typical of courtly love relationships, to a more assertive style. Her dress, relatively modest in earlier scenes, is suddenly voluptuous and revealing.[22]

The deer- and fox-hunting scenes are less clearly connected, although scholars have attempted to link each animal to Gawain's reactions in the parallel seduction scene. Attempts to connect the deer hunt with the first seduction scene have unearthed a few parallels. Deer hunts of the time, like courtship, had to be done according to established rules. Women often favoured suitors who hunted well and skinned their animals, sometimes even watching while a deer was cleaned.[22][23] The sequence describing the deer hunt is relatively unspecific and nonviolent, with an air of relaxation and exhilaration. The first seduction scene follows in a similar vein, with no overt physical advances and no apparent danger; the entire exchange is humorously portrayed.[22]

The boar-hunting scene is, in contrast, laden with detail. Boars were (and are) much more difficult to hunt than deer; approaching one with only a sword was akin to challenging a knight to single combat. In the hunting sequence, the boar flees but is cornered before a ravine. He turns to face Bertilak with his back to the ravine, prepared to fight. Bertilak dismounts and in the ensuing fight kills the boar. He removes its head and displays it on a pike. In the seduction scene, Bertilak's wife, like the boar, is more forward, insisting that Gawain has a romantic reputation and that he must not disappoint her. Gawain, however, is successful in parrying her attacks, saying that surely she knows more than he about love. Both the boar hunt and the seduction scene can be seen as depictions of a moral victory: both Gawain and Bertilak face struggles alone and emerge triumphant.[22]

Nature and chivalry

Some argue that nature represents a chaotic, lawless order which is in direct confrontation with the civilisation of Camelot throughout Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. The green horse and rider that first invade Arthur’s peaceful halls are iconic representations of nature's disturbance.[24] Nature is presented throughout the poem as rough and indifferent, constantly threatening the order of men and courtly life. Nature invades and disrupts order in the major events of the narrative, both symbolically and through the inner nature of humanity. This element appears first with the disruption caused by the Green Knight, later when Gawain must fight off his natural lust for Bertilak’s wife, and again when Gawain breaks his vow to Bertilak by choosing to keep the green girdle, valuing survival over virtue. Represented by the sin-stained girdle, nature is an underlying force, forever within man and keeping him imperfect (in a chivalric sense).[25] In this view, Gawain is part of a wider conflict between nature and chivalry, an examination of the ability of man's order to overcome the chaos of nature.[26]

Several critics have made exactly the opposite interpretation, reading the poem as a comic critique of the Christianity of the time, particularly as embodied in the Christian chivalry of Arthur's court. In its zeal to extirpate all traces of paganism, Christianity had cut itself off from the sources of life in nature and the female. The green girdle represents all the pentangle lacks. The Arthurian enterprise is doomed unless it can acknowledge the unattainability of the ideals of the Round Table, and, for the sake of realism and wholeness, recognize and incorporate the pagan values represented by the Green Knight.[27]

Games

The word gomen (game) is found 18 times in Gawain. Its similarity to the word gome (man), which appears 21 times, has led some scholars to see men and games as centrally linked. Games at this time were seen as tests of worthiness, as when the Green Knight challenges the court's right to its good name in a "Christmas game".[28] The "game" of exchanging gifts was common in Germanic cultures. If a man received a gift, he was obliged to provide the giver with a better gift or risk losing his honour, almost like an exchange of blows in a fight (or in a "beheading game").[29] The poem revolves around two games: an exchange of beheading and an exchange of winnings. These appear at first to be unconnected. However, a victory in the first game will lead to a victory in the second. Elements of both games appear in other stories; however, the linkage of outcomes is unique to Gawain.[2][11]

Times and seasons

Times, dates, seasons, and cycles within Gawain are often noted by scholars because of their symbolic nature. The story starts on New Year's Eve with a beheading and culminates on the next New Year's Day. Gawain leaves Camelot on All Saints Day and arrives at Bertilak's castle on Christmas Eve. Furthermore, the Green Knight tells Gawain to meet him at the Green Chapel in "a year and a day"—a period of time seen often in medieval literature.[4] Some scholars interpret the yearly cycles, each beginning and ending in winter, as the poet's attempt to convey the inevitable fall of all things good and noble in the world. Such a theme is strengthened by the image of Troy, a powerful nation once thought to be invincible which, according to the Aeneid, fell to the Greeks due to pride and ignorance. The Trojan connection shows itself in the presence of two virtually identical descriptions of Troy's destruction. The poem's first line reads: "Since the siege and the assault were ceased at Troy" and the final stanzaic line (before the bob and wheel) is "After the siege and the assault were ceased at Troy".[30]

Symbolism

Significance of the color green

Given the varied and even contradictory interpretations of the color green, its precise meaning in the poem remains ambiguous. In English folklore and literature, green was traditionally used to symbolise nature and its associated attributes: fertility and rebirth. Stories of the medieval period also used it to allude to love and the base desires of man.[32][33] Because of its connection with faeries and spirits in early English folklore, green also signified witchcraft, devilry and evil. It can also represent decay and toxicity.[34] When combined with gold, as with the Green Knight and the girdle, green was often seen as representing youth's passing.[35] In Celtic mythology, green was associated with misfortune and death, and therefore avoided in clothing.[36] The green girdle, originally worn for protection, became a symbol of shame and cowardice; it is finally adopted as a symbol of honour by the knights of Camelot, signifying a transformation from good to evil and back again; this displays both the spoiling and regenerative connotations of the color green.[36]

The Green Knight

Scholars have puzzled over the Green Knight's symbolism since the discovery of the poem. He could be a version of the Green Man, a mythological being connected with nature in medieval art, a Christian symbol, or the Devil himself. British medieval scholar C. S. Lewis said the character was "as vivid and concrete as any image in literature" and J. R. R. Tolkien said he was the "most difficult character" to interpret in Sir Gawain. His major role in Arthurian literature is that of a judge and tester of knights, thus he is at once terrifying, friendly, and mysterious.[36] He appears in only two other poems: The Greene Knight and King Arthur and King Cornwall.[37][38] Scholars have attempted to connect him to other mythical characters, such as Jack in the green of English tradition and to Al-Khidr,[39] but no definitive connection has yet been established.[39][40]

However, there is a possibility, as Alice Buchanan has argued, that the colour green is erroneously attributed to the Green Knight due to the poet's mistranslation or misunderstanding of the Irish word glas, which could either mean grey or green. In the Death of Curoi (one of the Irish stories from Bricriu's Feast), Curoi stands in for Bercilak, and is often called "the man of the grey mantle". Though the words usually used for grey in the Death of Curoi are lachtna or odar, roughly meaning milk-coloured and shadowy respectively, in later works featuring a green knight, the word glas is used and may have been the basis of misunderstanding.[41]

Girdle

The girdle's symbolic meaning, in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, has been construed in a variety of ways. Interpretations range from sexual in nature to spiritual. Those who argue for the sexual inference view the girdle as a "trophy".[42] However, it is not entirely clear who the "winner" is: Sir Gawain or Lady Bertilak. The girdle is given to Gawain by Lady Bertilak in order to keep him safe when he confronts the Green Knight. When Lord Bertilak returns home from his hunting trip, Gawain does not reveal the girdle to his host but, instead, hides it. This introduces the spiritual interpretation, that Gawain’s acceptance of the girdle is a sign of his faltering faith in God, at least in the face of death.[43] To some, the Green Knight is Christ, who overcomes death, while Gawain is the Every Christian, who in his struggles to follow Christ faithfully, chooses the easier path. In Sir Gawain, the easier choice is the girdle, which promises what Gawain most desires. Faith in God, alternatively, requires one’s acceptance that what one most desires does not always coincide with what God has planned. It is arguably best to view the girdle not as an either–or situation, but as a complex, multi-faceted symbol that acts to test Gawain in more ways than one. While Gawain is able to resist Bertilak’s wife’s sexual advances, he is unable to resist the powers of the girdle. Gawain is operating under the laws of chivalry which, evidently, have rules that can contradict each other. In the story of Sir Gawain, Gawain finds himself torn between doing what a damsel asks (accepting the girdle) and keeping his promise (returning anything given to him while his host is away).[44]

Pentangle

The pentangle on Gawain's shield is seen by many critics as signifying Gawain's perfection and power over evil.[45] The poem contains the only representation of such a symbol on Gawain's shield in the Gawain literature. What is more, the poet uses a total of 46 lines to describe the meaning of the pentangle; no other symbol in the poem receives as much attention or is described in such detail.[46] The poem describes the pentangle as a symbol of faithfulness and an "endless knot". In line 625, it is described as "a sign by Solomon". Solomon, the third king of Israel, in the 10th century BC, was said to have the mark of the pentagram on his ring, which he received from the archangel Michael. The pentagram seal on this ring was said to give Solomon power over demons.[47]

Along these lines, some academics link the Gawain pentangle to magical traditions. In Germany, the symbol was called a Drudenfuß and was placed on household objects to keep out evil.[48] The symbol was also associated with magical charms that, if recited or written on a weapon, would call forth magical forces. However, concrete evidence tying the magical pentagram to Gawain's pentangle is scarce.[48][49]

Gawain’s pentangle also symbolises the "phenomenon of physically endless objects signifying a temporally endless quality."[50] Many poets use the symbol of the circle to show infinity or endlessness, but Gawain’s poet insisted on using something more complex. In medieval number theory, the number five is considered a "circular number", since it "reproduces itself in its last digit when raised to its powers".[51] Furthermore, it replicates itself geometrically; that is, every pentangle has a smaller pentagon that allows a pentangle to be embedded in it and this "process may be repeated forever with decreasing pentangles".[51] Thus, by reproducing the number five, which in medieval number symbolism signified incorruptibility, Gawain's pentangle represents his eternal incorruptibility.[52]

The Lady's Ring

Gawain's refusal of the Lady Bertilak's ring has major implications for the remainder of the story. While the modern student may tend to pay more attention to the girdle as the eminent object offered by the lady, readers in the time of Gawain would have noticed the significance of the offer of the ring as they believed that rings, and especially the embedded gems, had talismanic properties.[53] This is especially true of the lady's ring as scholars believe it to be a ruby or carbuncle, indicated when the Gawain-Poet describes it as a "brygt sunne" (line 1819),[54] a "fiery sun."[55] Given the importance of magic rings in Arthurian romance, this remarkable ring would also have been believed to protect the wearer from harm.[56]

Numbers

The poet highlights number symbolism to add symmetry and meaning to the poem. For example, three kisses are exchanged between Gawain and Bertilak's wife; Gawain is tempted by her on three separate days; Bertilak goes hunting three times, and the Green Knight swings at Gawain three times with his axe. The number two also appears repeatedly, as in the two beheading scenes, two confession scenes, and two castles.[57] The five points of the pentangle, the poet adds, represent Gawain's virtues, for he is "faithful five ways and five times each".[58] The poet goes on to list the ways in which Gawain is virtuous: all five of his senses are without fault; his five fingers never fail him, and he always remembers the five wounds of Christ, as well as the five joys of the Virgin Mary. The fifth five is Gawain himself, who embodies the five moral virtues of the code of chivalry: "friendship, generosity, chastity, courtesy, and piety".[59] All of these virtues reside, as the poet says, in the "Endless Knot" of the pentangle, which forever interlinks and is never broken.[60] This intimate relationship between symbol and faith allows for rigorous allegorical interpretation, especially in the physical role that the shield plays in Gawain's quest.[61] Thus, the poet makes Gawain the epitome of perfection in knighthood through number symbolism.[62]

The number five is also found in the structure of the poem itself. Sir Gawain is 101 stanzas long, traditionally organised into four 'Fitts' of 21, 24, 34, and 22 stanzas. These divisions, however, have since been disputed; scholars have begun to believe that they are the work of the copyist and not of the poet. The original manuscript features a series of capital letters added after the fact by another scribe, and some scholars argue that these additions were an attempt to restore the original divisions. These letters divide the manuscript into nine parts. The first and last parts are 22 stanzas long. The second and second-to-last parts are only one stanza long, and the middle five parts are eleven stanzas long. The number eleven is associated with transgression in other medieval literature (being one more than ten, a number associated with the Ten Commandments). Thus, this set of five elevens (55 stanzas) creates the perfect mix of transgression and incorruption, suggesting that Gawain is faultless in his faults.[62]

Wounds

At the story's climax, Gawain is wounded superficially in the neck by the Green Knight's axe. During the medieval period, the body and the soul were believed to be so intimately connected that wounds were considered an outward sign of inward sin. The neck, specifically, was believed to correlate with the part of the soul related to will, connecting the reasoning part (the head) and the courageous part (the heart). Gawain's sin resulted from using his will to separate reasoning from courage. By accepting the girdle from the lady, he employs reason to do something less than courageous—evade death in a dishonest way. Gawain's wound is thus an outward sign of an internal wound. The Green Knight's series of tests shows Gawain the weakness that has been in him all along: the desire to use his will pridefully for personal gain, rather than submitting his will in humility to God. The Green Knight, by engaging with the greatest knight of Camelot, also reveals the moral weakness of pride in all of Camelot, and therefore all of humanity. However, the wounds of Christ, believed to offer healing to wounded souls and bodies, are mentioned throughout the poem in the hope that this sin of prideful "stiffneckedness" will be healed among fallen mortals.[63][64]

Interpretations

Gawain as medieval romance

Many critics argue that Sir Gawain and the Green Knight should be viewed, above all, as a romance. Medieval romances typically recount the marvellous adventures of a chivalrous, heroic knight, often of super-human ability, who abides by chivalry's strict codes of honour and demeanour, embarks upon a quest and defeats monsters, thereby winning the favour of a lady. Thus, medieval romances focus not on love and sentiment (as the term "romance" implies today), but on adventure.[65]

Gawain's function, as medieval scholar Alan Markman says, "is the function of the romance hero … to stand as the champion of the human race, and by submitting to strange and severe tests, to demonstrate human capabilities for good or bad action."[66] Through Gawain's adventure, it becomes clear that he is merely human. The reader becomes attached to this human view in the midst of the poem's romanticism, relating to Gawain's humanity while respecting his knightly qualities. Gawain "shows us what moral conduct is. We shall probably not equal his behaviour, but we admire him for pointing out the way."[66]

In viewing the poem as a chivalric romance, many scholars see it as intertwining chivalric and courtly love laws under the English Order of the Garter. The group's motto, 'honi soit qui mal y pense', or "Shamed be he who finds evil here," is written at the end of the poem. Some critics describe Gawain's peers wearing girdles of their own as evidence of the origin of the Order of the Garter. However, in the parallel poem The Greene Knight, the lace is white, not green, and is considered the origin of the collar worn by the knights of the Bath, not the Order of the Garter.[67] The motto on the poem was probably written by a copyist and not by the original author. Still, the connection made by the copyist to the Order is not extraordinary.[68]

Christian interpretations

The poem is in many ways deeply Christian, with frequent references to the fall of Adam and Eve and to Jesus Christ. Scholars have debated the depth of the Christian elements within the poem by looking at it in the context of the age in which it was written, coming up with varying views as to what represents a Christian element of the poem and what does not. For example, some critics compare Sir Gawain to the other three poems of the Gawain manuscript. Each has a heavily Christian theme, causing scholars to interpret Gawain similarly. Comparing it to the poem Cleanness (also known as Purity), for example, they see it as a story of the apocalyptic fall of a civilisation, in Gawain's case, Camelot. In this interpretation, Sir Gawain is like Noah, separated from his society and warned by the Green Knight (who is seen as God's representative) of the coming doom of Camelot. Gawain, judged worthy through his test, is spared the doom of the rest of Camelot. King Arthur and his knights, however, misunderstand Gawain's experience and wear garters themselves. In Cleanness the men who are saved are similarly helpless in warning their society of impending destruction.[30]

One of the key points stressed in this interpretation is that salvation is an individual experience difficult to communicate to outsiders. In his depiction of Camelot, the poet reveals a concern for his society, whose inevitable fall will bring about the ultimate destruction intended by God. Gawain was written around the time of the Black Death and Peasants' Revolt, events which convinced many people that their world was coming to an apocalyptic end and this belief was reflected in literature and culture.[30] However, other critics see weaknesses in this view, since the Green Knight is ultimately under the control of Morgan le Fay, usually viewed as a figure of evil in Camelot tales. This makes the knight's presence as a representative of God problematic.[28]

While the character of the Green Knight is usually not viewed as a representation of Christ in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, critics do acknowledge a parallel. Lawrence Besserman, a specialist in medieval literature, explains that "the Green Knight is not a figurative representative of Christ. But the idea of Christ's divine/human nature provides a medieval conceptual framework that supports the poet's serious/comic account of the Green Knight's supernatural/human qualities and actions." This duality exemplifies the influence and importance of Christian teachings and views of Christ in the era of the Gawain Poet.[36]

Furthermore, critics note the Christian reference to Christ's crown of thorns at the conclusion of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. After Gawain returns to Camelot and tells his story regarding the newly acquired green sash, the poem concludes with a brief prayer and a reference to "the thorn-crowned God".[69] Besserman theorises that "with these final words the poet redirects our attention from the circular girdle-turned-sash (a double image of Gawain's "yntrawpe/renoun") to the circular Crown of Thorns (a double image of Christ's humiliation turned triumph)."[36]

Throughout the poem, Gawain encounters numerous trials testing his devotion and faith in Christianity. When Gawain sets out on his journey to find the Green Chapel, he finds himself lost, and only after praying to the Virgin Mary does he find his way. As he continues his journey, Gawain once again faces anguish regarding his inevitable encounter with the Green Knight. Instead of praying to Mary, as before, Gawain places his faith in the girdle given to him by Bertilak's wife. From the Christian perspective, this leads to disastrous and embarrassing consequences for Gawain as he is forced to reevaluate his faith when the Green Knight points out his betrayal.[70] Another interpretation sees the work in terms of the perfection of virtue, with the pentangle representing the moral perfection of the connected virtues, the Green Knight as Christ exhibiting perfect fortitude, and Gawain as slightly imperfect in fortitude by virtue of flinching when under the threat of death. [71]

An analogy is also made between Gawain's trial and the Biblical test that Adam encounters in the Garden of Eden. Adam succumbs to Eve just as Gawain surrenders to Bertilak's wife by accepting the girdle.[70] Although Gawain sins by putting his faith in the girdle and not confessing when he is caught, the Green Knight pardons him, thereby allowing him to become a better Christian by learning from his mistakes.[72] Through the various games played and hardships endured, Gawain finds his place within the Christian world.

Feminist interpretations

Feminist literary critics see the poem as portraying women's ultimate power over men. Morgan le Fay and Bertilak's wife, for example, are the most powerful characters in the poem—Morgan especially, as she begins the game by enchanting the Green Knight. The girdle and Gawain's scar can be seen as symbols of feminine power, each of them diminishing Gawain's masculinity. Gawain's misogynist passage,[73] in which he blames all of his troubles on women and lists the many men who have fallen prey to women's wiles, further supports the feminist view of ultimate female power in the poem.[74]

In contrast, others argue that the poem focuses mostly on the opinions, actions, and abilities of men. For example, on the surface, it appears that Bertilak's wife is a strong leading character.[75] By adopting the masculine role, she appears to be an empowered individual, particularly in the bedroom scene. This is not entirely the case, however. While the Lady is being forward and outgoing, Gawain's feelings and emotions are the focus of the story, and Gawain stands to gain or lose the most.[76] The Lady "makes the first move", so to speak, but Gawain ultimately decides what is to become of those actions. He, therefore, is in charge of the situation and even the relationship.[76]

In the bedroom scene, both the negative and positive actions of the Lady are motivated by her desire.[77] Her feelings cause her to step out of the typical female role and into that of the male, thus becoming more empowered.[78] At the same time, those same actions make the Lady appear adulterous; some scholars compare her with Eve in the Bible.[79] By forcing Gawain to take her girdle, i.e. the apple, the pact made with Bertilak—and therefore the Green Knight—is broken.[80] In this sense, it is clear that at the hands of the Lady, Gawain is a "good man seduced".[80]

Postcolonial interpretations

From 1350 to 1400—the period in which the poem is thought to have been written—Wales experienced several raids at the hands of the English, who were attempting to colonise the area. The Gawain poet uses a North West Midlands dialect common on the Welsh–English border, potentially placing him in the midst of this conflict. Patricia Clare Ingham is credited with first viewing the poem through the lens of postcolonialism, and since then a great deal of dispute has emerged over the extent to which colonial differences play a role in the poem. Most critics agree that gender plays a role, but differ about whether gender supports the colonial ideals or replaces them as English and Welsh cultures interact in the poem.[81]

A large amount of critical debate also surrounds the poem as it relates to the bi-cultural political landscape of the time. Some argue that Bertilak is an example of the hybrid Anglo-Welsh culture found on the Welsh–English border. They therefore view the poem as a reflection of a hybrid culture that plays strong cultures off one another to create a new set of cultural rules and traditions. Other scholars, however, argue that historically much Welsh blood was shed well into the 14th century, creating a situation far removed from the more friendly hybridisation suggested by Ingham. To support this argument further, it is suggested that the poem creates an "us versus them" scenario contrasting the knowledgeable civilised English with the uncivilised borderlands that are home to Bertilak and the other monsters that Gawain encounters.[81]

In contrast to this perception of the colonial lands, others argue that the land of Hautdesert, Bertilak’s territory, has been misrepresented or ignored in modern criticism. They suggest that it is a land with its own moral agency, one that plays a central role in the story. Bonnie Lander, for example, argues that the denizens of Hautdesert are "intelligently immoral", choosing to follow certain codes and rejecting others, a position which creates a "distinction … of moral insight versus moral faith". Lander thinks that the border dwellers are more sophisticated because they do not unthinkingly embrace the chivalric codes but challenge them in a philosophical, and—in the case of Bertilak's appearance at Arthur’s court—literal sense. Lander’s argument about the superiority of the denizens of Hautdesert hinges on the lack of self-awareness present in Camelot, which leads to an unthinking populace that frowns on individualism. In this view, it is not Bertilak and his people, but Arthur and his court, who are the monsters.[82]

Gawain's journey

Several scholars have attempted to find a real-world correspondence for Gawain's journey to the Green Chapel. The Anglesey islands, for example, are mentioned in the poem. They exist today as a single island off the coast of Wales.[83] In line 700, Gawain is said to pass the "Holy Head", believed by many scholars to be either Holywell or the Cistercian abbey of Poulton in Pulford. Holywell is associated with the beheading of Saint Winifred. As the story goes, Winifred was a virgin who was beheaded by a local leader after she refused his sexual advances. Her uncle, another saint, put her head back in place and healed the wound, leaving only a white scar. The parallels between this story and Gawain's make this area a likely candidate for the journey.[84]

Gawain's trek leads him directly into the centre of the Pearl Poet's dialect region, where the candidates for the locations of the Castle at Hautdesert and the Green Chapel stand. Hautdesert is thought to be in the area of Swythamley in northwest Midland, as it lies in the writer's dialect area and matches the topographical features described in the poem. The area is also known to have housed all of the animals hunted by Bertilak (deer, boar, fox) in the 14th century.[85] The Green Chapel is thought to be in either Lud's Church or Wetton Mill, as these areas closely match the descriptions given by the author.[86] Ralph Elliott located the chapel ("two myle henne" v1078) from the old manor house at Swythamley Park at the bottom of a valley ("bothm of the brem valay" v2145) on a hillside ("loke a littel on the launde, on thi lyfte honde" v2147) in an enormous fissure ("an olde caue,/or a creuisse of an olde cragge" v2182-83).[87]

Homoerotic Interpretations

According to medieval scholar Richard Zeikowitz, the Green Knight represents a threat to homosocial friendship in his medieval world. Zeikowitz argues that the narrator of the poem seems entranced by the Knight's beauty, homoeroticising him in poetic form. The Green Knight's attractiveness challenges the homosocial rules of King Arthur's court and poses a threat to their way of life. Zeikowitz also states that Gawain seems to find Bertilak as attractive as the narrator finds the Green Knight. Bertilak, however, follows the homosocial code and develops a friendship with Gawain. Gawain's embracing and kissing Bertilak in several scenes thus represents not a homosexual but a homosocial expression. Men of the time often embraced and kissed and this was acceptable under the chivalric code. Nonetheless, the Green Knight blurs the lines between homosociality and homosexuality, representing the difficulty medieval writers sometimes had in separating the two.[88]

Carolyn Dinshaw argues that the poem may have been a response to accusations that Richard II had a male lover—an attempt to reestablish the idea that heterosexuality was the Christian norm. Around the time the poem was written, the Catholic Church was beginning to express concerns about kissing between males. Many religious figures were trying to make the distinction between strong trust and friendship between males and homosexuality. Still, the Pearl Poet seems to have been simultaneously entranced and repulsed by homosexual desire. In his other poem Cleanness, he points out several grievous sins, but spends lengthy passages describing them in minute detail. His obsession seems to carry into Gawain in his descriptions of the Green Knight.[89]

Beyond this, Dinshaw proposes that Gawain can be read as a woman-like figure. He is the passive one in the advances of Lady Bertilak, as well as in his encounters with Lord Bertilak, where he acts the part of a woman in kissing the man. However, while the poem does have homosexual elements, these elements are brought up by the poet in order to establish heterosexuality as the normal lifestyle of Gawain's world. The poem does this by making the kisses between Lady Bertilak and Gawain sexual in nature, but rendering the kisses between Gawain and Lord Bertilak "unintelligible" to the medieval reader. In other words, the poet portrays kisses between a man and a woman as having the possibility of leading to sex, while in a heterosexual world kisses between a man and a man are portrayed as having no such possibility.[89]

Modern adaptations

Books

Though the surviving manuscript dates from the fourteenth century, the first published version of the poem did not appear until as late as 1839, when Sir Frederic Madden of the British Museum recognized the poem as worth reading.[90] Madden's scholarly, Middle English edition of the poem was followed in 1898 by the first Modern English translation – a prose version by literary scholar Jessie L. Weston.[90] In 1925, J.R.R. Tolkien and E.V. Gordon published a scholarly edition of the Middle English text of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight; a revised edition of this text was prepared by Norman Davis and published in 1967. The book, featuring a text in Middle English with extensive scholarly notes, is frequently confused with the translation into Modern English that Tolkien prepared, along with translations of Pearl and Sir Orfeo, late in his life.[91] Many editions of the latter work, first published in 1975, shortly after his death, list Tolkien on the cover as author rather than translator.[92]

For students, especially undergraduate students, the text is usually given in translation. Notable translators include Jessie Weston, whose 1898 prose translation and 1907 poetic translation took many liberties with the original; Theodore Banks, whose 1929 translation was praised for its adaptation of the language to modern usage;[93] and Marie Borroff, whose imitative translation was first published in 1967 and "entered the academic canon" in 1968, in the second edition of the Norton Anthology of English Literature. In 2010, her (slightly revised) translation was published as a Norton Critical Edition, with a foreword by Laura Howes.[94] In 2007, Simon Armitage, who grew up near the Gawain poet's purported residence, published a translation which attracted attention in the US and the United Kingdom,[95] and was published in the United States by Norton,[96] which replaced Borroff's translation with Armitage's for the ninth edition of the Norton Anthology of English Literature. Other modern translations include those by Brian Stone, James Winny, Helen Cooper, W. S. Merwin, Jacob Rosenberg, William Vantuono, Joseph Glaser, Bernard O'Donoghue, John Gardner, and Francis Ingledew.

In 2014, Zach Weiner published a children's book called Augie and the Green Knight that is a take on this tale. Though the protagonist of the book is a young, modern-day girl, the events of the book largely follow the Arthurian legend. In 1997, Gerald Morris published a version of the story called The Squire, His Knight, and His Lady.

Film and television

The poem has been adapted to film twice, on both occasions by writer-director Stephen Weeks: first as Gawain and the Green Knight in 1973[97] and again in 1984 as Sword of the Valiant: The Legend of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, featuring Miles O'Keeffe as Gawain and Sean Connery as the Green Knight.[98] Both films have been criticised for deviating from the plot. Gawain, for example, has an adventure in the 1973 version which is not a part of the poem between the time he leaves Camelot and the time he arrives at Bertilak's castle, in which he travels through New Earth to find his parents. Also, Bertilak and the Green Knight are never connected.[99] French/Australian director Martin Beilby directed a short (30') film adaptation in 2014.[100] There have been at least two television adaptations, Gawain and the Green Knight in 1991[101] and the animated Sir Gawain and the Green Knight in 2002.[102] The BBC broadcast a documentary presented by Simon Armitage in which the journey depicted in the poem is traced, utilising what are believed to be the actual locations.[103]

Theatre

The Tyneside Theatre company presented a stage version of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight at the University Theatre, Newcastle at Christmas 1971. It was directed by Michael Bogdanov and adapted for the stage from the translation by Brian Stone.[104] The music and lyrics were composed by Iwan Williams using medieval carols, such as the Boar's Head Carol, as inspiration and folk instruments such as the Northumbrian pipes, whistles and bhodran to create a "rough" feel. Stone had referred Bogdanov to Cuchulain and the Beheading Game, a sequence which is contained in The Grenoside Sword dance. Bogdanov found the pentangle theme to be contained in most sword dances, and so incorporated a long sword dance while Gawain lay tossing uneasily before getting up to go to the Green Chapel. The dancers made the knot of the pentangle around his drowsing head with their swords. The interlacing of the hunting and wooing scenes was achieved by frequent cutting of the action from hunt to bed-chamber and back again, while the locale of both remained on-stage.

In 1992 Simon Corble created an adaptation with medieval songs and music for The Midsommer Actors' Company.[105] performed as walkabout productions in the summer 1992[106] at Thurstaston Common and Beeston Castle and in August 1995 at Brimham Rocks, North Yorkshire.[107] Corble later wrote a substantially revised version which was produced indoors at the O'Reilly Theatre, Oxford in February 2014.[108][109]

Opera

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight was first adapted as an opera in 1978 by the composer Richard Blackford on commission from the village of Blewbury, Oxfordshire. The libretto was written for the adaptation by the children's novelist John Emlyn Edwards. The "Opera in Six Scenes" was subsequently recorded by Decca between March and June 1979 and released on the Argo label[110] in November 1979.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight was adapted into an opera called Gawain by Harrison Birtwistle, first performed in 1991. Birtwistle's opera was praised for maintaining the complexity of the poem while translating it into lyric, musical form.[111] Another operatic adaptation is Lynne Plowman's Gwyneth and the Green Knight, first performed in 2002. This opera uses Sir Gawain as the backdrop but refocuses the story on Gawain's female squire, Gwyneth, who is trying to become a knight.[112] Plowman's version was praised for its approachability, as its target is the family audience and young children, but criticised for its use of modern language and occasional preachy nature.[113]

References

- ↑ Simpson, James. "A Note on Middle English Meter." In Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (A New Verse Translation) by Simon Armitage. Norton, 2008. p. 18.

- 1 2 3 The Norton Anthology of English Literature. Ed. Stephen Greenblatt. 8th ed. Vol. B. New York, London: W. W. Norton and Co., 2006. pp. 19–21 and 160–161. ISBN 0-393-92833-0

- 1 2 "Web Resources for Pearl-poet Study: A Vetted Selection". Univ. of Calgary. Retrieved 2007-04-01.

- 1 2 For reasons not entirely understood, the Celts used the phrase "a year and a day", to refer to exactly one year. See for example W. J. McGee's "The Beginning of Mathematics." American Anthropologist. (Oct 1899) Vol. 1 Iss. 4 pp. 646–674.

- ↑ Masters of British Literature Volume A. Pearson Longman. 2008. pp. 200–201. ISBN 9780321333995.

- ↑ "Pearl: Introduction". Medieval Institute Publications, Inc. 2001. Retrieved 2007-04-02.

- ↑ Turville-Petre, Thorlac. The Alliterative Revival. Woodbridge: Brewer etc., 1977. pp. 126–129. ISBN 0-85991-019-9

- ↑ Burrow, J. Ricardian Poetry. London: Routledge and K. Paul, 1971. ISBN 0-7100-7031-4 pp. 4–5

- ↑ "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight". The Broadview Anthology of British Literature: The Medieval Period, Vol. 1., ed. Joseph Black, et al. Toronto: Broadview Press, Introduction, p. 235. ISBN 1-55111-609-X

- 1 2 Nelles, William. "The Pearl-Poet". Cyclopedia of World Authors, Fourth Revised Edition Database: MagillOnLiterature Plus, 1958.

- 1 2 Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Edited J.R.R. Tolkien and E.V. Gordon, revised Norman Davis, 1925. introduction, xv. ASIN B000IPU84U

- ↑ Peterson, Clifford J (1974). "The Pearl-Poet and John Massey of Cotton, Cheshire". The Review of English Studies, New Series 25 (99): 257–266. doi:10.1093/res/xxv.99.257.

- 1 2 "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight". Representative Poetry Online. University of Toronto Libraries. 1 August 2002. Archived from the original on 19 January 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-20.

- 1 2 3 Brewer, Elisabeth. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Woodbridge: D.S. Brewer, 1992. ISBN 0-85991-359-7

- 1 2 Friedman, Albert B. "Morgan le Fay in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight." Speculum. Vol. 35, No. 2 (Apr 1960) pp. 260–274

- ↑ Hahn, Thomas. "The Greene Knight". In Sir Gawain: Eleven Romances and Tales. Western Michigan University Medieval Institute Publications, 2000. ISBN 1-879288-59-1. Full text: The Greene Knight

- ↑ Hahn, Thomas. "The Turke and Sir Gawain". In Sir Gawain: Eleven Romances and Tales. Western Michigan University Medieval Institute Publications, 2000. ISBN 1-879288-59-1. Online: The Turke and Sir Gawain.

- ↑ Hahn, Thomas. "The Carle of Carlisle", in Sir Gawain: Eleven Romances and Tales. Western Michigan University Medieval Institute Publications, 2000. ISBN 1-879288-59-1. Online: The Carle of Carlisle.

- ↑ Kittredge, George Lyman. A Study of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Harvard University Press, 1960. p. 76. ASIN B0006AWBXS

- ↑ Kittredge, p. 83

- ↑ Burrow, J.A. A Reading of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. London: Kegan Paul Ltd., 1965. p. 162. ISBN 0-7100-8695-4

- 1 2 3 4 Burnley, J.D. (1973). "The Hunting Scenes in 'Sir Gawain and the Green Knight' ".". The Yearbook of English Studies 3: 1–9. doi:10.2307/3506850.

- ↑ The "hyndez" (hinds) first described in the poem are probably from red deer, a species with large antlers like the American elk, while the subsequent "dos and of oþer dere" (does and other deer) likely refer to the smaller fallow deer. (Ong, Walter J. "The Green Knight's Harts and Bucks". Modern Language Notes. (December 1950) 65.8 pp. 536–539.)

- ↑ Cawley, A. C. 'Pearl, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight':"...the Green Knight, alias Sir Bertilak, is an immensely vital person who is closely associated with the life of nature: his greenness, the birds and flies of his decorative embroidery, his beard as great as a bush, the holly branch in his hand, the energy he displays as a huntsman-all give him kinship with the physical world outside the castle."

- ↑ Woods, William F. "Nature and the Inner Man in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight". The Chaucer Review, Vol. 36, No. 3, 2002, pp. 209–227.

- ↑ Green, Richard Hamilton. "Gawain's Shield and the Quest for Perfection". ELH. (June 1962) 29.2 pp. 121–139.

- ↑ This interpretation was first advanced by John Speirs in Scrutiny, vol.XVI, iv, 1949 (incorporated in his Medieval English Poetry: The Non-Chaucerian Tradition, rev.ed. 1962. Similar interpretations were later offered by Francis Berry in The Pelican Guide to English Literature: The Age of Chaucer, 1954; Goldhurst, "The Green and the Gold: The Major Theme of Sit Gawain and the Green Knight, College English, Nov. 1958; A.C, Spearing, The Gawain-Poet: A Critical Study, 1970; W. A. Davenport, The Art of the Gawain-Poet, 1978; J. Tambling, "A More Powerful Life: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight", Haltwhistle Quarterly 9, 1981; and K. Sagar, "Sir Gawain and the Green Girdle", in his Literature and the Crime Against Nature, 2005.

- 1 2 Goodlad, Lauren M. (1987) "The Gamnes of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight", Comitatus: A Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies, Vol. 18, Article 4.

- ↑ Harwood, Britton J (1991). "Gawain and the Gift". PMLA 106 (3): 483–99. doi:10.2307/462781.

- 1 2 3 Clark, S. L.; Wasserman, Julian N. (1986). "The Passing of the Seasons and the Apocalyptic in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight". South Central Review 3 (1): 5–22. doi:10.2307/3189122.

- ↑ Robertson, D.W. Jr. "Why the Devil Wears Green". Modern Language Notes. (November 1954) 69.7 pp. 470–472.

- ↑ Chamberlin, Vernon A. "Symbolic Green: A Time-Honored Characterizing Device in Spanish Literature". Hispania. (March 1968) 51.1 pp. 29–37

- ↑ Goldhurst, William. "The Green and the Gold: The Major Theme of Gawain and the Green Knight". College English. (November 1958) 20.2 pp. 61–65. doi:10.2307/372161

- ↑ Williams, Margaret. The Pearl Poet, His Complete Works. Random House, 1967. ASIN B0006BQEJY

- ↑ Lewis, John S. "Gawain and the Green Knight". College English. (October 1959) 21.1 pp. 50–51

- 1 2 3 4 5 Besserman, Lawrence. "The Idea of the Green Knight". ELH. (Summer 1986) 53.2 The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 219–239.

- ↑ Hahn, Thomas. "The Greene Knight". In Sir Gawain: Eleven Romances and Tales. Western Michigan University Medieval Institute Publications, 2000 p. 314. ISBN 1-879288-59-1

- ↑ Hahn, Thomas. "King Arthur and King Cornwall". In Sir Gawain: Eleven Romances and Tales. Western Michigan University Medieval Institute Publications, 2000. p. 427. ISBN 1-879288-59-1

- 1 2 Lasater, Alice E. Spain to England: A Comparative Study of Arabic, European, and English Literature of the Middle Ages. University Press of Mississippi, 1974. ISBN 0-87805-056-6

- ↑ Rix, Michael M. "A Re-Examination of the Castleton Garlanding". Folklore. (June 1953) 64.2 pp. 342–344

- ↑ Buchanan, Alice (June 1932). "The Irish Framework of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight". PLMA 47 (2): 315–338. doi:10.2307/457878.

- ↑ . Friedman, Albert B. Morgan le Fay in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Medieval Academy of America. Speculum, Vol. 35, No. 2, 1960

- ↑ Berger, Sidney E. "Gawain's Departure from the Peregrinatio". Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 1985.

- ↑ Burrow, J.A. A Reading of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. London: Kegan Paul Ltd., 1965

- ↑ The poem contains the first recorded use of the word pentangle in English (Oxford English Dictionary Online).

- ↑ Arthur, Ross G. Medieval Sign Theory and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987. pp. 22, 26. ISBN 0-8020-5717-9

- ↑ LaBossière, Camille R., and Gladson, Jerry A. "Solomon", in A Dictionary of Biblical Tradition in English Literature. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1992 p. 722.

- 1 2 Hulbert, J. R. "Syr Gawayn and the Grene Knyzt (Concluded)". Modern Philology. (April 1916) 13.12 pp. 689–730.

- ↑ Jackson, I. "Sir Gawain's Coat of Arms." The Modern Language Review. (January 1920) 15.1 pp. 77–79.

- ↑ Arthur, pp. 33–34.

- 1 2 Arthur, p. 34.

- ↑ Arthur, p. 35.

- ↑ Cooke, Jessica (1998). "The Lady's 'Blushing' Ring in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight". The Review of English Studies 49 (193): 1–8. doi:10.1093/res/49.193.1.

- ↑ Andrew, Malcolm; Ronald Waldron (1996). The Poems of the Pearl Manuscript. Exeter: University of Exeter Press. p. 273. ISBN 0-85989-514-9.

- ↑ Borroff, Marie (2001). Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Patience, Pearl: Verse Translations. New York: Norton. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-393-97658-8.

- ↑ Cooke, "The Lady's 'Blushing,'" 2,5.

- ↑ Howard, Donald R. "Structure and Symmetry in Sir Gawain". Speculum. (July 1964) 39.3 pp. 425–433.

- ↑ Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Book 2, Stanza 27.

- ↑ Kittredge, p. 93.

- ↑ Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Book 2, Stanza 28.

- ↑ Mills, M. "Christian Significance and Roman Tradition in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight." Critical Studies of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Eds. Donald R. Howard & Christian Zacher. 2nd ed. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 1970. 85–105.

- 1 2 Robertson, Michael. "Stanzaic Symmetry in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight". Speculum. (October 1982) 57.4 pp. 779–785.

- ↑ Reichardt, Paul F. (1984). "Gawain and the Image of the Wound". PMLA 99 (2): 154–61. doi:10.2307/462158. JSTOR 462158.

- ↑ Arthur, pp. 121–123.

- ↑ Frye, Northrop. Anatomy of Criticism, p. 186. ISBN 0-691-01298-9

- 1 2 Markman, Alan M. "The Meaning of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight". PMLA. (September 1957) 72.4 pp. 574–586

- ↑ Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, second edition. Ed. J.R.R. Tolkien and E.V. Gordon, 1925, note to lines 2514ff. ASIN B000IPU84U

- ↑ The Norton Anthology of English Literature, eighth edition, Vol. BEd Stephen Greenblatt. New York, London: W. W. Norton and Co., 2006, p. 213 (footnote). ISBN 0-393-92833-0

- ↑ Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, line 2529.

- 1 2 Cox, Catherine. "Genesis and Gender in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight", The Chaucer Review. (2001) 35.4 pp. 379–390. Retrieved on 22 September 2007.

- ↑ Beauregard,David. “Moral Theology in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: The Pentangle, the Green Knight, and the Perfection of Virtue,” Renascence XLV.3 (2013), 146-62.

- ↑ Pugh, Tison. "Gawain and the Godgames". Christianity and Literature. (2002) 51.4 pp. 526–551. Retrieved on 30 September 2007, from Saint Louis University

- ↑ Mills, David (1970). "The Rhetorical Function of Gawain's Antifeminism?". Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 71: 635–4.

- ↑ Heng, Geraldine (1991). "Feminine Knots and the Other Sir Gawain and the Green Knight". PMLA 106 (3): 500–514. doi:10.2307/462782.

- ↑ Burns, E. Jane. "Courtly Love: Who Needs It? Recent Feminist Work in the Medieval Tradition". Signs. (Autumn 2001) 27.1 pp. 23–57. Retrieved on 7 September 2007 from JSTOR

- 1 2 Burns, p. 24

- ↑ Rowley, Sharon M (2003). "Textual Studies, Feminism, and Performance in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight". The Chaucer Review 38: 158–177. doi:10.1353/cr.2003.0022.

- ↑ Rowley, p. 161

- ↑ Cox, p. 378

- 1 2 Cox, p. 379

- 1 2 Arner, Lynn (Summer 2006). "The Ends of Enchantment: Colonialism and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight". Texas Studies in Literature and Language 48 (2): 79–101. doi:10.1353/tsl.2006.0006.

- ↑ Lander, Bonnie (2007). "The Convention of Innocence and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight's Literary Sophisticates". Parergon 24 (1): 41–66. doi:10.1353/pgn.2007.0046.

- ↑ Twomey, Michael. "Anglesey and North Wales". Travels With Sir Gawain. Ithaca Univ. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

- ↑ Twomey, Michael. "The Holy Head and the Wirral". Travels With Sir Gawain. Ithaca Univ. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

- ↑ Twomey, Michael. "Hautdesert". Travels With Sir Gawain. Ithaca Univ. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

- ↑ Twomey, Michael. "The Green Chapel". Travels With Sir Gawain. Ithaca Univ. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

- ↑ RWV Elliott. "Searching for the Green Chapel" in JK Lloyd Jones (ed). Chaucer's Landscapes and Other Essays. Aust. Scholarly Publishing. Melbourne (2010) pp 293–303 at p300.

- ↑ Zeikowitz, Richard E. "Befriending the Medieval Queer: A Pedagogy for Literature Classes." College English: Special Issue: Lesbian and Gay Studies/Queer Pedagogies. Vol. 65 No. 1 (Sep 2002) pp. 67–80

- 1 2 Dinshaw, Carolyn. "A Kiss Is Just a Kiss: Heterosexuality and Its Consolations in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight." Diacritics. Vol. 24 No. 2/3 (Summer 1994) pp. 204–226

- 1 2 Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, ed. Marie Borroff and Laura Howes, New York: Norton, 2010, pg. vii

- ↑ Tolkien, J.R.R. (1980). Christopher Tolkien, ed. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Pearl, and Sir Orfeo. Random House. ISBN 978-0-345-27760-2.

- ↑ White, Michael (2003). Tolkien: A Biography. New American Library. ISBN 0-451-21242-8.

- ↑ Farley, Frank E. (1930). "Rev. of Banks, Sir Gawain, and Andrew, Sir Gawain". Speculum 5 (2): 222–24. doi:10.2307/2847870. JSTOR 2847870.

- ↑ Baragona, Alan (2012). "Rev. of Howes, Borroff, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight". Journal of English and Germanic Philology 111 (4): 535–38. doi:10.5406/jenglgermphil.111.4.0535.

- ↑ Hirsch, Edward (16 December 2007). "A Stranger in Camelot". The New York Times. p. 7.1. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ↑ Armitage, Simon (2007). Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: A New Verse Translation. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-06048-5.

- ↑ "Gawain and the Green Knight (1973)". imdb. Retrieved 2007-04-13.

- ↑ "Sword of the Valiant: The Legend of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (1984)". imdb. Retrieved 2007-04-13.

- ↑ Mills, Maldwyn (1991). "Review". The Yearbook of English Studies 21: 336–337.

- ↑ "Sire Gauvain et le Chevalier Vert". IMDB.

- ↑ "Gawain and the Green Knight (1991) (TV)". imdb. Retrieved 2007-04-13.

- ↑ "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (2002) (TV)". imdb. Retrieved 2007-04-13.

- ↑ "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight". BBC Four. 17 August 2010. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ↑ Stone, Brian (1974). Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Penguin. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-140-44092-8.

- ↑ http://www.corble.co.uk/page_1212407743203.html

- ↑ Turner, Francesca (7 July 1992). "Gawayne and the Green Knight". The Guardian.

- ↑ photos from Midsommer Actors archive on flickr

- ↑ Nirula, Srishti (16 February 2014). "Sir Gawain pulls our strings". The Oxford Student. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ↑ Hopkins, Andrea (15 February 2014). "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight". Daily Info, Oxford. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ↑ Argo ZK 85: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight; an opera in six scenes by Richard Blackford. The Decca Record Company Ltd. Argo Division, 115 Fulham Road, London, SW3 6RR: 1979.

- ↑ Bye, Anthony (May 1991). "Birtwistle's Gawain". The Musical Times 132 (1779): 231–33. doi:10.2307/965691. JSTOR 965691.

- ↑ "Opera – Gwyneth and the Green Knight". lynneplowman.co.uk. Archived from the original on 14 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-03.

- ↑ Kimberley, Nick (11 May 2003). "Classical: The footstomping way to repay a sound investment". The Independent on Sunday. Retrieved 2008-01-26.

External links

- Online texts

- High-resolution, full-sized scan of entire manuscript

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight at Archive.org

- JRR Tolkien and EV Gordon's Edition

- The poem in Middle English

-

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight public domain audiobook at LibriVox - Google Books results

- General information

- The Gawain/Pearl Poet from the University of Calgary

- The Camelot Project Info on Sir Gawain

- Luminarium SGGK Website

- Oxford Bibliographies: Bibliography on Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

- BBC documentary tour of locations thought to be found in the poem... Holywell, the River Mersey, the 'Wild Wirral', the Peak District, the Roaches, and Lud Chapel

- Sir Gawain Introduction - Article introducing various translations and adaptations of Sir Gawain

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

|