Gauss circle problem

In mathematics, the Gauss circle problem is the problem of determining how many integer lattice points there are in a circle centred at the origin and with radius r. The first progress on a solution was made by Carl Friedrich Gauss, hence its name.

The problem

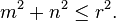

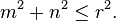

Consider a circle in R2 with centre at the origin and radius r ≥ 0. Gauss' circle problem asks how many points there are inside this circle of the form (m,n) where m and n are both integers. Since the equation of this circle is given in Cartesian coordinates by x2 + y2 = r2, the question is equivalently asking how many pairs of integers m and n there are such that

If the answer for a given r is denoted by N(r) then the following list shows the first few values of N(r) for r an integer between 0 and 12 followed by the list of values  rounded to the nearest integer:

rounded to the nearest integer:

- 1, 5, 13, 29, 49, 81, 113, 149, 197, 253, 317, 377, 441 (sequence A000328 in OEIS)

- 0, 3, 13, 28, 50, 79, 113, 154, 201, 254, 314, 380, 452 (sequence A075726 in OEIS)

Bounds on a solution and conjecture

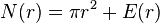

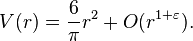

The area inside a circle of radius r is given by πr2, and since a square of area 1 in R2 contains one integer point,  can be expected to be roughly πr2. So it should be expected that

can be expected to be roughly πr2. So it should be expected that

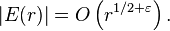

for some error term E(r) of relatively small absolute value. Finding a correct upper bound for |E(r)| is thus the form the problem has taken. Note that r need not be an integer. After  one has

one has  At these places

At these places  increases by

increases by  after which it decreases (at a rate of

after which it decreases (at a rate of  ) until the next time it increases.

) until the next time it increases.

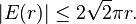

Gauss managed to prove[1] that

Hardy[2] and, independently, Landau found a lower bound by showing that

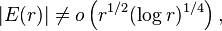

using the little o-notation. It is conjectured[3] that the correct bound is

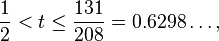

Writing |E(r)| ≤ Crt, the current bounds on t are

with the lower bound from Hardy and Landau in 1915, and the upper bound proved by Huxley in 2000.[4]

Exact forms

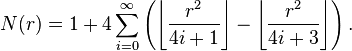

The value of N(r) can be given by several series. In terms of a sum involving the floor function it can be expressed as:[5]

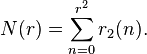

A much simpler sum appears if the sum of squares function r2(n) is defined as the number of ways of writing the number n as the sum of two squares. Then[1]

Generalisations

Although the original problem asks for integer lattice points in a circle, there is no reason not to consider other shapes or conics, indeed Dirichlet's divisor problem is the equivalent problem where the circle is replaced by the rectangular hyperbola.[3] Similarly one could extend the question from two dimensions to higher dimensions, and ask for integer points within a sphere or other objects. If one ignores the geometry and merely considers the problem an algebraic one of Diophantine inequalities then there one could increase the exponents appearing in the problem from squares to cubes, or higher.

The primitive circle problem

Another generalisation is to calculate the number of coprime integer solutions m, n to the equation

This problem is known as the primitive circle problem, as it involves searching for primitive solutions to the original circle problem.[6] If the number of such solutions is denoted V(r) then the values of V(r) for r taking small integer values are

Using the same ideas as the usual Gauss circle problem and the fact that the probability that two integers are coprime is 6/π2, it is relatively straightforward to show that

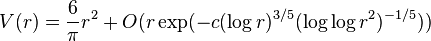

As with the usual circle problem, the problematic part of the primitive circle problem is reducing the exponent in the error term. At present the best known exponent is 221/304 + ε if one assumes the Riemann hypothesis.[6] Without assuming the Riemann hypothesis, the best known upper bound is

for a positive constant c.[6] In particular, no bound on the error term of the form 1 − ε for any ε > 0 is currently known that does not assume the Riemann Hypothesis.

Notes

- 1 2 G.H. Hardy, Ramanujan: Twelve Lectures on Subjects Suggested by His Life and Work, 3rd ed. New York: Chelsea, (1999), p.67.

- ↑ G.H. Hardy, On the Expression of a Number as the Sum of Two Squares, Quart. J. Math. 46, (1915), pp.263–283.

- 1 2 R.K. Guy, Unsolved problems in number theory, Third edition, Springer, (2004), pp.365–366.

- ↑ M.N. Huxley, Integer points, exponential sums and the Riemann zeta function, Number theory for the millennium, II (Urbana, IL, 2000) pp.275–290, A K Peters, Natick, MA, 2002, MR 1956254.

- ↑ D. Hilbert and S. Cohn-Vossen, Geometry and the Imagination, New York: Chelsea, (1999), pp.37–38.

- 1 2 3 J. Wu, On the primitive circle problem, Monatsh. Math. 135 (2002), pp.69–81.