Gateway Project

| Gateway Project | |

|---|---|

| Overview | |

| Type | High-speed rail |

| Status | Proposed |

| Termini |

Newark, New Jersey New York City |

| Services | Northeast Corridor |

| Operation | |

| Planned opening | 2024 |

| Owner | Amtrak |

| Character | Underground, elevated |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge |

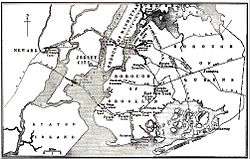

The Gateway Project is a proposed high-speed rail corridor to alleviate the bottleneck along the Northeast Corridor (NEC) between Newark, New Jersey, and New York City, New York. If constructed, the project would add 25 train slots during peak periods to the current system used by Amtrak (AMTK) and New Jersey Transit (NJT), which has reached full capacity. The planned right-of-way would parallel the current one between Newark Penn Station and New York Penn Station (NYP) in Midtown Manhattan. The project would build new rail bridges in the New Jersey Meadowlands, dig new tunnels under the Hudson Palisades and the Hudson River, convert parts of the James Farley Post Office into a rail station, and add a terminal annex to NY Penn. Some previously planned improvements already underway have also been incorporated into the Gateway plan.

The Gateway Project was unveiled in 2011, one year after the cancellation of the somewhat similar Access to the Region's Core (ARC) project, and was originally projected to cost $14.5 billion and take 14 years to build. In 2015, Amtrak reported that environmental and design work was underway, estimated the project's total cost at $20 billion, and said construction would start in 2019 or 2020 and last four to five years.[1]

The administration of U.S. president Barack Obama has called the Gateway Project the most vital piece of infrastructure that needs to be built in the United States. It remains unclear how or if it will be funded.[2] In September 2015 joint letter to Obama, New Jersey Governor Chris Christie and New York Governor Andrew Cuomo offered to pay half of the project’s cost if the federal government picks up the rest, but did not identify how they would fund it.[3][4][5] Port Authority of New York and New Jersey Chairman John J. Degnan said in May 2015 that the agency "would step up to the plate" with regard to funding the project.[6] The governors have asked the agency to oversee the project.[7]

In 2015, Amtrak said that damage done to the existing trans-Hudson tunnels by 2012's Hurricane Sandy had made their replacement urgent. Construction of a "tunnel box" that would preserve the right-of-way on Manhattan's West Side began in September 2013, using $185 million in Sandy recovery and resilience funding. In November 2015, it was announced by Amtrak, U.S. Senators Cory Booker and Charles Schumer, and Governers Christie and Cuomo that a new Gateway Development Corporation would be created to oversee the project with the federal government paying for 50% of its costs and the states sharing the rest.[8][9]

Announcement and initial phases

The Gateway Project was unveiled on February 7, 2011, by Boardman and New Jersey Senators Frank Lautenberg and Robert Menendez.[10][11][12][13] The announcement also included endorsements from New York Senator Charles Schumer and Amtrak's Board of Directors. Officials said Amtrak would take the lead in seeking financing; a list of potential sources included the states of New York and New Jersey, the City of New York, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANYNJ), and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) as well as private investors.[14][15][16]

As of late 2011, two parts of the project were underway: the replacement of the Portal Bridge over the Hackensack River and the development of Moynihan Station in Manhattan. Environmental impact statements are completed and the design and engineering of the new bridges has begun.[17][18][19][20][21] The ceremonial groundbreaking of the first phase of the conversion of the Farley P.O. to a new Moynihan Station took place in October 2010.[22] Some funding for the projects comes from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.[23][24][25][26]

Funding

In 2011, the project was projected to cost $13.5 billion and wrap up in 2020. In April 2011, Amtrak asked that $1.3 billion in USDOT funding for NEC rail corridor improvements be allocated to Gateway and related projects.[27][28] In November 2011, Congress allocated $15 million for engineering work.[29][30][31]

In 2012, revised projections put the cost at $14.5 billion and completion date at 2025.[32] In April 2012, the U.S. Senate appropriations subcommittee on transportation proposed to provide another $20 million; that awaits further congressional approval.[33][34]

While New Jersey officlals have said the state will pay its "fair share" of the project, they have committed to no specific dollar amount.[35] In 2013, it was estimated NJ's contribution would be between $3–5 billion.[36] The source of further funding remains unclear. The state had planned to spend some $600 million on ARC;[37] some of the completed design and engineering work has been used by Amtrak to develop the Gateway Project.[38]

In September 2012, Schumer estimated that the project would need $20 million in 2013 and $100 million in 2014 to keep it from dying.[39]

In December 2012, Amtrak requested $276 million from Congress to upgrade infrastructure damaged by Hurricane Sandy that would also eventually support trains run along the new Gateway Project right-of-way.[40][41][42] That funding, which had been revised to $188 million, was deleted from the legislation.[43] In 2013, an additional $185 million in funding for the "tunnel box" was provided as a relief and resiliency project in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy. Additional funding has not been identified.[44]

Port Authority of New York and New Jersey Chairman John J. Degnan said in May 2015 that the agency "would step up to the plate" with regard to funding the project.[6]

Gateway Development Corporation

The Gateway Development Corporation will be formed under the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. PANYNJ board members form both states, the USDOT and Amtrak will comprise the corporation' board. staff will be provided by the PANYNJ and Amtrak. The corporation will oversee planning, environmental, design, engineering and construction work. It would also seek federal grants and apply for loans.[45] It remains unclear how the money will be raised.[46]

Background

Right-of-way

The right-of-way was originally developed by the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR)[47] in conjunction with the 1910 opening of Pennsylvania Station (New York City) which required the construction of the Portal Bridge over the Hackensack River and the North River Tunnels under the Hudson Palisades and Hudson River. The following year the Manhattan Transfer was opened in the Kearny Meadows to allow changes between steam and electric locomotives. This also provided for passenger transfers to/from its former main terminal at Exchange Place in Jersey City or the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad (H&M), the forerunner of today's Port Authority Trans Hudson (PATH).[48] The Dock Bridge over the Passaic River was opened in conjunction with adjacent new Pennsylvania Station (Newark) in 1935.[49][50] In 1937, the H&M was extended over a second span, making the transfer in the meadows redundant.[51]

In 1949, the PRR discontinued its ferry system on the Hudson and in 1961 closed its Exchange Place station.[52] In 1962, it agreed to the demolition of its Manhattan station in exchange for a smaller one under a new Madison Square Garden.[53] In 1967, the Aldene Plan was implemented, requiring the floundering Central Railroad of New Jersey (CNJ), Reading (RDG), and Lehigh Valley (LV) railroads, to travel into Newark Penn with continuing service to New York Penn.[48][54] The following year the PRR merged with New York Central (NYC), but the new Penn Central (PC) declared bankruptcy on June 21, 1970. In 1976, its long distance service (including part of today's Northeast Corridor and Empire Corridor) was taken over by Amtrak, which had been founded in 1971.[55] Conrail was created in 1976 to bail out numerous Northeast railroads, including the commuter service on the CNJ and the LV.[56][57] In 1983, when the corporation divested its passenger rail operations, they were taken over by New Jersey Transit (NJT), which had been created in 1979 to operate much of the state's bus system.[58]

In 1991, New Jersey Transit opened the Waterfront Connection, extending service on some non-electricfied trains which had previously terminated at Newark Penn Station to Hoboken.[59] In 1996, it began its Midtown Direct service, rerouting some trains from the west which previously terminated at Hoboken Terminal to New York Penn.[60][61] Secaucus Junction was opened in 2003, allowing passengers travelling from the north to transfer to Northeast Corridor Line, North Jersey Coast Line, or Midtown Direct trains, though not to Amtrak, which does not stop there. Between 1976 and 2010, the number of New Jersey Transit weekday trains crossing the Hudson using the North River Tunnels (under contract with Amtrak[62]) increased from 147 to 438.[12]

Trans-Hudson crossings

The other rail system crossing the Hudson was developed by the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad, partially in conjunction with the PRR,[63] and taken over by PANYNJ in 1962.[64] Direct trans-Hudson rail service to Lower Manhattan from Newark Penn is provided by Port Authority Trans Hudson (PATH), a rapid transit system with additional terminals at World Trade Center and Herald Square in Manhattan, and at Hoboken Terminal and Journal Square in Hudson County.[65]

There are three vehicular crossings of the lower Hudson River.[66] The Holland Tunnel, opened in 1927, is minimally used for public transportation. The George Washington Bridge, opened in 1931, is used by suburban buses to GWB Bus Terminal. Its lower level, opened in 1962, is the last new river crossing.[67] The Lincoln Tunnel, composed of three tubes opened in 1937, 1945 and 1954,[68] is one of the busiest tunnels in the world. Its eastern terminus is connected via ramps to the Port Authority Bus Terminal, the gateway for most NJT bus traffic entering Manhattan.[69] Despite the Lincoln Tunnel XBL (express bus lane) during the morning peak there are often long delays due to traffic congestion and the limited capacity of the bus terminal for deboarding passengers.[70][71][72] The PANYNJ 2007–2016 Capital Plan[73] included a new bus garage in Midtown, so empty buses could avoid unnecessarily returning through the tunnel but the agency scrapped this feature in October 2011.[74] More than 6,000 bus trips are made through the tunnel and bus terminal daily. In December 2011, the New Jersey Assembly passed a resolution calling upon the PANYNJ to address the issue of congestion.[75] In May 2012, the commissioner of NJDOT suggested that some NJT routes could originate/terminate at other Manhattan locations, notably the East Side. The arrangement would require the approval of the New York City Department of Transportation (NYCDOT) to use bus stops.[76]

Access to the Region's Core

Launched in 1995 by PANYNJ, NJT, and MTA, Access to the Region's Core (ARC) was a Major Investment Study that looked at public transportation ideas for the New York metropolitan area. It found that long-term goals would best be met by better connections to and in-between the region's major rail stations in Midtown Manhattan, Penn Station and Grand Central Terminal.[78] The East Side Access project, including tunnels under the East River and the East Side of Manhattan, which would divert some LIRR traffic to Grand Central, is expected to be completed in 2019.[79]

The Trans-Hudson Express Tunnel or THE Tunnel, which later took on the name of the study itself, was meant to address the western, or Hudson River, crossing. Engineering studies determined that structural interferences made a new terminal connected to Grand Central or the current Penn Station unfeasible and its final design involved boring under the current rail yard to a new deep cavern terminal station under 34th Street.[80][81] While Amtrak had acknowledged that the region represented a bottleneck in the national system and had originally planned to complete work by 2040,[82] its timetable for beginning the project was advanced in part due to the cancellation of ARC, a project similar in scope, but with differences in design.[83] That project, which did not include direct Amtrak participation,[82][84] was cancelled in October 2010 by New Jersey governor Chris Christie, who cited potential cost overruns.[85] Amtrak briefly engaged the governor in attempt to revive the ARC Tunnel and use preliminary work done for it, but those negotiations soon broke down.[15][82][84] Amtrak said it was not interested in purchasing any of the work.[86] Senator Menendez later said some preparatory work done for ARC may be used for the new project.[87] Costs for the project were $117 million for preliminary engineering, $126 million for final design, $15 million for construction and $178 million real estate property rights ($28 million in New Jersey and $150 million in New York City). Additionally, a $161 million partially refundable pre-payment of insurance premiums was also made.[37]

Existing and new infrastructure along right of way

The current route, about 11 miles (18 km) long, includes infrastructure that is more than 100 years old. The system operates at capacity during peak hours — 23 trains per hour — and limits speed for safety reasons. The new high-speed route would run parallel to the current right-of-way, enabling dispatching alternatives, potential speed increases, and up to 25 more trains per hour. There are no plans for Amtrak to stop at Secaucus Junction, the only intermediate station and a major interchange point in the NJT system.

Newark Penn, Dock Bridge, Harrison PATH Station

Six tracks connect Newark Penn Station and the adjacent Dock Bridge over the Passaic River at 40°44′05″N 74°9′51″W / 40.73472°N 74.16417°W. The station and the west span of the bridge, carrying three tracks, were built in 1935. The east span, opened in 1937, carries one outbound track, and the two Port Authority Trans Hudson (PATH) tracks entering and leaving the station. The bridge, owned by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANY/NJ), underwent repairs as recently as 2009.[88] To the northeast lies the Harrison PATH Station. Between the bridge and the station AMTK and NJT trains are aligned on three center tracks to pass through it, with the PATH using side platforms. While not part of the Gateway Project, the station itself is undergoing a $173 million reconstruction and expansion funded by the PANY/NJ which owns and operates the PATH rapid transit system. Passenger use is expected to grow as the area develops; it already includes the Red Bull Arena.[89] Maps for the Gateway Project indicate that an additional, or fourth track for the NEC will be added.[12]

Kearny Meadows – Sawtooth Bridge

At Kearny Junction at 40°44′37″N 74°07′36″W / 40.7435°N 74.1267°W, east of the former Manhattan Transfer, the rights-of-way of Amtrak, and PATH, and several NJT lines converge and run parallel to each other. While there is no junction with PATH, NJT trains can switch tracks, depending on their terminal of origination or destination, enabling Midtown Direct trains on the Morris and Essex Lines to join or depart the Northeast Corridor.[60][61] The single track limited-use Waterfront Connection connects some lines using diesel trains on Hoboken Terminal trips with the NEC to the west.[59] Currently the NEC runs on two tracks northeast of the junction. Plans call for expansion to four tracks, requiring the construction of bridges[12] in the Kearny Meadows at Newark Turnpike and Belleville Turnpike. Plans call for the replacement of the Sawtooth Bridge at 40°44′38″N 74°7′30″W / 40.74389°N 74.12500°W carrying the NEC over Hoboken Terminal lines.[90][91]

Portal Bridge

The 1910 Portal Bridge at 40°45′13″N 74°5′41″W / 40.75361°N 74.09472°W, a two-track, rail-only, 961-foot (293 m) swing bridge over the Hackensack River between Kearny and Secaucus, limits train speeds and crossings and requires frequent and costly maintenance.[18][92] Its lowest beams are 23 feet (7.0 m) above the water, so it opens regularly for shipping,[92] though not during weekday rush hours, when trains have priority.[93]

In December 2008, the Federal Railroad Administration approved a $1.34 billion project to replace the Portal Bridge with two new bridges: a three-track bridge to the north, and a two-track bridge to the south.[18] In 2009, New Jersey applied for funding from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 and on January 28, 2010, received $38.5 million for design.[94] Current plans call for two two-track bridges.[12] Cycling advocates, with Lautenberg's support, are lobbying to include bike paths that would become part of the East Coast Greenway.[20][95] Construction on the new bridges had been scheduled to begin in 2010 and wrap up in 2017, at which time the Portal Bridge would have been dismantled.[11][12][17][18][83][96] In April 2011, Amtrak applied for $570 million for construction from US DOT. New Jersey was expected to contribute $150 million.[28]

In October 2015, $16 million TIGER grant was awarded and will be used to support early construction activities such as realignment of a 138kV transmission monopole, constructing a temporary fiber optic cable pole line, building a finger pier construction access structure, a service access road and a 560-foot retaining wall.[97][98]

Secaucus Junction – Bergen Loop

Opened on December 15, 2003, Secaucus Junction, at 40°45′42″N 74°04′30″W / 40.76161°N 74.074985°W, is an interchange station served by nine of New Jersey Transit's rail lines, and is sited where Hoboken Terminal trains intersect with those traveling along the Northeast Corridor. Passenger transfers are possible, but there is no rail junction. While the ARC had planned a loop to create a junction,[99] original plans for the Gateway Project did not. Amtrak trains pass through the station, but do not stop there, nor are there plans to include an Amtrak stop.[12] In April 2012, Amtrak announced that the Project might include a "Bergen Loop" connecting NJT's Main Line/Bergen County Line and Pascack Valley Line and Metro-North Railroad's (MTA) West of Hudson service[100]) to the NEC at Secaucus Junction.[101][102] MTA constituencies are encouraging the agency to include funding for the loop its capital plan.[103]

Gateway Tunnel

The current North River Tunnels allow a maximum of 23 one-way crossings per hour;[104] the Gateway proposal would allow an additional 25 trains per hour. In May 2014 Amtrak C.E.O. Joseph Boardman told the Regional Plan Association that there was something less than 20 years before one or both of the tunnels would have to be shut down.[105]

The ARC Tunnel was to be built in three sections: under the Hudson Palisades, under the Hudson River, and under the streets of Manhattan, where it would have dead-ended. The Gateway Tunnel will likely be built along the footprint of the Palisades and river sections, but will enable trains to join the current interlocking once it emerges. A flying junction is planned for later stages.[12] This will allow Amtrak and NJT to continue to use the East River Tunnels and Sunnyside Yards for staging, storage, and carrying Amtrak NEC trains.

In April 2011, $188 million in federal funding was requested for preliminary engineering studies and environmental analysis.[28][106]

Palisades Tunnel

A groundbreaking for ARC was held on June 8, 2009[107] for new underpass at 40°45′56″N 74°2′14″W / 40.76556°N 74.03722°W, under Tonnelle Avenue in North Bergen near the site western portal of the tunnel through Hudson Palisades just south of the North River Tunnels. The land, which cost $26.3 million, is owned by NJT.[108] A tunneling contract for the Palisades Tunnel was awarded on May 5, 2010 to Skanska.[109][110] Maps indicate this part of the Gateway Tunnel would follow a route to the Weehawken-Hoboken border.[12] In October 2012, in an eminent domain case for a property in Weehawken New Jersey Transit acquired a parcel in the path of the tunnel for $8.5 million.[111]

Hudson River Tunnel

The Gateway Hudson River tunnel, one point of which would be at 40°45′17″N 74°01′00″W / 40.75479°N 74.01677°W, will travel from a point at Weehawken Cove under the Hudson River and its eastern portal south of West Side Yard in Manhattan.[12] Engineering studies for ARC along this route had been deemed unfeasible.[112] Surveys of properties which would or would not be affected by underground construction at underground eastern end of the ARC Tunnel had been completed.[113]

Hudson Yards "tunnel box"

The West Side Yard is to be developed as a residential and commercial district on a platform constructed over them as part of the Hudson Yards project.[114][115] According to Schumer, the only place for an Amtrak portal in Manhattan is in the West Side Yard. That might conflict with the Hudson Yards project, which broke ground in late 2012.[39] In February 2013, Amtrak officials said they would commission a project to preserve a right-of-way for future use to be built with $120 million to $150 million in federal funds.[116][117][118] in June 2013 it was announced that $183 million had been dedicated to the "tunnel box" as part of Hurricane Sandy recovery funding.[36][119][120] Construction began in September 2013 at 40°45′17″N 74°00′14″W / 40.754661°N 74.003783°W and is expected to take two years.[121] The underground concrete casing is 800 ft (240 m) long, 50 ft (15 m) wide, and approximately 35 ft (11 m) tall.[122] Amtrak awarded Tutor Perini a $133m contract to build a section of box tunnel.[123]

Amtrak, NJ Transit, and the MTA have applied to the Federal Transit Administration for a $65 million matching grant for another 105 ft (32 m) long structure to preserve the right-of-way at 11th Avenue in Manhattan[124][125] under a viaduct that was rehabilitated in 2009–2011.[126][127]

New York Penn Station

The original Pennsylvania Station in New York was completed in 1910. The station's air rights were optioned in the 1950s and called for the razing of the head-house and train shed, while the tracks, well below street level, would remain. Demolition began in October 1963. The current Penn Station, part of the Pennsylvania Plaza complex which includes Madison Square Garden (MSG), was completed in 1968.[53] On July 24, 2013, the New York City Council voted to extend the MSG lease just ten years, in an effort to have the arena move to a different location so that a new station structure can be built in its place.[128][129][130]

Penn Station, at 40°45′02″N 73°59′38″W / 40.750638°N 73.993899°W, is quoted to be as the "busiest, most congested, passenger transportation facility in North America on a daily basis",[131] used by Amtrak, New Jersey Transit, and the Long Island Railroad (LIRR), and served by several New York City Subway lines. Between 1976 and 2010 weekday train movements increased 89%, from 661 to 1,248, reaching what is considered to be capacity.[12] In 2010, the station saw 550,000 daily boardings/alightings.[16][132][133]

Moynihan Station

In the early 1990s, then-New York Senator Daniel Moynihan announced plans to convert portions of the James Farley Post Office, at 40°45′4.4″N 73°59′42.64″W / 40.751222°N 73.9951778°W, to a train station.[132][134] Opened in 1912, soon after the original Pennsylvania Station, the landmark building is the city's main post office. It stands across from Penn Plaza and is built over tracks approaching the station from the west.[135][136]

The project languished for almost two decades, until the final chunk of the $267 million in funding for the first phase of the conversion was secured in early 2010. The phase will expand and improve the 33rd Street Connector between Penn Station and its West End Concourse. Located under the grand staircase of the post office, the concourse will be widened to serve nine of Pennsylvania Station's 11 platforms, and new street entrances will be opened from the southeast and northeast corners of the Farley building.[137] Some $169 million provided by federal and state sources was already in place[138] when a Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery (TIGER) Grant arrived in early 2010.[21] A ceremonial groundbreaking and signing for the $83 million in funds took place in October.[22]

No timetable has been set for further phases, which may include public-private partnerships.[139] In April 2011 New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced that the state had applied for $49.8 million in federal funding for the final design of Phase 2 of the station's conversion,[140] but was not honored.[131]

The Gateway Project will have little effect on the first phase of the Farley conversion.[12] The second phase of the renovation is planned to make the post office Amtrak's New York Gateway, though in December 2011 it said that it would likely be unable to afford increased operating costs if it should re-locate. The unsuccessful application leaves the project unfunded. The agency redeveloping the building is being folded into the PANYNJ in the belief that it can better handle and oversee reconstruction as well as provide or secure monies.[131] In May 2012, the PANYNJ announced that a $270 million contract for the first phase, including that the concourse expansion under 8th Avenue had been awarded. Completion is expected sometime in 2016.[141][142]

Penn Station South

Plans call for Penn Station South to be located on the block south of the current New York Penn Station at 31st Street and diagonally across Eighth Avenue from the post office, on land which is currently privately held.[144] While the PANYNJ had been acquiring land for ARC along its route, acquisition south of the station has not begun.[13] It is likely the entire block would be razed and made available for highrise construction after completion of the station.[145] Plans call for seven tracks served by four platforms in what will be a terminal annex to the entire station complex.[12] In April 2011 Amtrak requested $50 million in federal funding for preliminary engineering and environmental analysis.[28][106]

In 2014 it was estimated that would cost $404 million to purchase 35 properties in order to build a new terminal at the location.[146] Based on development guidelines from the New York City Planning Commission, it is estimated at that 2015 prices it would cost between $769 million to $1.3 billion just to buy the block bounded to the north and south by 31st and 30th streets, and to the east and west by Seventh and Eighth avenues. Real estate prices are 2½ times higher now than they were in 2012 according to prominent real estate firm Cushman & Wakefield.[147][148]

Related projects

Other projects in the New York metropolitan area are planned as part of the NEC Next Generation High Speed Rail, including the northern and southern approaches to the Gateway Project.[149]

New Brunswick-Trenton high-speed upgrade

In May 2011, $450 million was dedicated to increase capacity on one of the NEC's busiest segments, a 24-mile (39 km) section between New Brunswick and Trenton. The planned six-year project will upgrade signals and electrical power systems, including catenary wires, to improve reliability, increase train speeds, and allow more frequent high-speed trains.[150][151][152] In July 2011, a bill passed by the House of Representatives threatened funding for the project and others announced at the same time,[153][154] but the money was released the following month.[155] The project, along with the purchase of new train sets, is expected to raise speeds on the segment to 180 mph (290 km/h).[155] In September 2012, Acela test trains hit 165 mph (266 km/h) over the segment.[156][157] (The 2012 tests did not break the longtime record on this stretch of track: 170 mph (270 km/h), set on December 20, 1967, by the U.S.-built UAC TurboTrain. This also stands as the record top speed for a North American train.[158][159][160]) The track work is one of several projects planned for the "New Jersey Speedway" section of the NEC, which include a new station at North Brunswick, the Mid-Line Loop (a flyover for reversing train direction), and the re-construction of County Yard, to be done in coordination with NJT.[161]

Harold Interlocking and Hutchinson River

Over 750 LIRR, NJT, and Amtrak trains travel through the Harold Interlocking every day, causing frequent conflicts and delays.[155] In May 2011, a $294.7 million federal grant was awarded to address congestion at the USA's busiest rail junction and part of the Sunnyside Yard in Queens. The work will allow for a dedicated track to the New York Connecting Railroad right of way for AMTK trains arriving from or bound for New England, thus avoiding NJT and LIRR traffic.[162][163][164] A new flyover will allow Amtrak trains to travel through the interlocking separately from LIRR trains, and NJ TRANSIT trains on their way to Sunnyside.[155] Financing for the project was placed in jeopardy by House of Representatives in July 2011 which voted to divert the funding to unrelated projects.,[154] but was later obligated so that work on the project can begin in 2012.[155]

Amtrak has applied for $15 million for the environmental impact studies and preliminary engineering design to examine replacement options for the more than 100-year-old, low-level movable Pelham Bay Bridge over the Hutchinson River in The Bronx. The goal is for a new bridge to support expanded service and speeds up to 110 mph (177 km/h).[106]

Subway service

While not part of the Gateway Project, Amtrak's announcement included a proposal to extend the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) 7 Subway Extension three blocks east to New York Penn Station from the current station at 11th Avenue and 34th Street. This would provide service to the Javits Convention Center and a one-seat ride to Grand Central Terminal, the city's other major train terminal on the East Side of Manhattan at 42nd Street.[12] Shortly before the introduction of Gateway, the New York City Economic Development Corporation voted to budget up to $250,000 for a feasibility study of a Hudson River tunnel for an extension to Secaucus Junction awarded to Parsons Brinckerhoff, a major engineering firm that had been working on the ARC tunnel.[165][166] In October 2011, Bloomberg reiterated his support for the NJ extension, estimated to cost around $10 billion and take ten years to complete, indicating that he would give approval by the end of his third term in 2013. Environmental-impact studies and a full business plan are required before the proposal proceeds.[167] It was likely that the two projects – Gateway and the subway line – would have been in competition for funding.[168] In April 2012, citing budget considerations, the director of the MTA effectively scuttled the project and said that it was doubtful the extension would be built in the foreseeable future, suggesting that the Gateway Project was a much more likely solution to congestion at Hudson River crossings.[169] The report was released in April 2013.[170][171] In a November 2013 Daily News opinion article, the president of the Real Estate Board of New York and the chairman of Edison Properties called for the line to be extended to Secaucus in tunnels to be shared with the Gateway Project.[172] In November 2013 the New Jersey Assembly passed a Resolution 168[173] supporting the extension of the line to Hoboken and Secaucus.[174]

See also

References

- ↑ "Take a ride inside the aging Hudson River train tunnels that would cost billions to replace (VIDEO)". The Star-Ledger.

- ↑ McGeehan, Patrick (May 7, 2015). "Obama Administration Urges Fast Action on New Hudson River Rail Tunnels". The New York Times. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- ↑ HIggs, Larry (September 15, 2015). "Christie, Cuomo ask Obama for money to build new rail tunnel, pledge state funds". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ Fitzsimmons, Emma G. (September 16, 2015). "Cuomo and Christie Say States Can Pay Half of Hudson Rail Tunnel Project". The New York Times. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ Tangle, Andrew (September 15, 2015). "Christie, Cuomo Ask Obama to Split Hudson River Tunnel Costs". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- 1 2 Maag, Christopher (May 7, 2015). "Port Authority chairman pledges to back Amtrak’s Hudson River tunnel project". The Record. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ↑ "TRENTON, N.J.: Taxpayer price tag for transportation projects is unclear - Business". CentreDaily.com. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- ↑ http://www.northjersey.com/news/officials-corporation-will-oversee-new-hudson-rail-tunnel-feds-will-split-cost-1.1454035

- ↑ http://www.nj.com/traffic/index.ssf/2015/11/booker_brokers_deal_on_entity_to_oversee_gateway_t.html

- ↑ Rouse, Karen (February 8, 2011). "Amtrak president details Gateway Project at Rutgers lecture". Bergen Record. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- 1 2 Frassinelli, Mike (February 6, 2011). "N.J. senators, Amtrak official to announce new commuter train tunnel project across the Hudson". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "Gateway Project" (PDF). Amtrak. February 2011. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

- 1 2 McGeehan, Patrick (February 7, 2011). "With One Plan for a Hudson Tunnel Dead, Senators Offer Another Option". The New York Times. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- ↑ "Lautenberg, Menendez Join Amtrak to Announce New Trans-Hudson Gateway Tunnel Project" (Press release). Lautenberg/US Senate press release. February 7, 2011. Retrieved February 21, 2011.

- 1 2 Frassinelli, Mike (February 8, 2011). "Gov. Christie says new Gateway tunnel plan addresses his ARC project cost concerns". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- 1 2 Caruso, Lisa (February 7, 2011). "Amtrak Proposes $13.5 Billion New Jersey Rail Project". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- 1 2 "Portal Bridge Capacity Enhancement". Amtrak, New Jersey Transit, U.S Department of Transportation. Retrieved February 8, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Belsen, Ken (December 31, 2008). "Approval Given for New Jersey Rail Bridges". The New York Times. Retrieved February 8, 2011.

- ↑ Frassinelli, Mike (January 28, 2010). "NJ Transit announces $38.5M for Portal Bridge project, names executive director". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved February 8, 2011.

- 1 2 Whiten, Jon (February 8, 2010). "Advocates Want Bike/Ped Path as Part of Portal Bridge Project". Jersey City Independent. Retrieved February 8, 2011.

- 1 2 "TIGER grant provides final piece of the Moynihan Station funding puzzle". United States Department of Transportation. October 19, 2010. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- 1 2 Bagli, Charles (October 18, 2010). "A Ceremonial Start for Moynihan Station". The New York Times. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- ↑ "The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act" (PDF). Njtransit.com. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Tangel, Andrew (February 1, 2015). "Work on New Hudson Train Tunnels Chugs Along". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ↑ "Amtrak Seeks $1.3 billion for Gateway Project and Next-Generation High-Speed Rail on NEC". Amtrak. April 4, 2011. Retrieved April 8, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Jackson, Herb (April 4, 2011), "Amtrak seeking $1.3B for Hudson River tunnel planning, bridge replacement", The Record, retrieved April 10, 2011

- ↑ Frassinelli, Mike (November 18, 2011). "Engineering work to begin on Gateway train tunnel under Hudson River, Congress approves $15M for project". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved November 22, 2011.

- ↑ Boburg, Shawn (November 2, 2011). "Senate OKs $15M in design funds for NJ-NY tunnel". The Record. Retrieved November 2, 2011.

- ↑ "U.S. Senate Approves Funding For NJ-NY Rail Tunnel Design". NJToday.com. November 2, 2011. Retrieved November 2, 2011.

- ↑ "Senate Committee OKs $20 Million For Gateway Tunnel Project". CBS. April 4, 2012. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Lautenberg, Menendez Announce $20 Million For Gateway Tunnel Project Approved In Senate Committee" (Press release). Senate.gov. April 19, 2012. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ↑ "Senate Appropriations Committee approves $20 million for Gateway Tunnel", Hudson Reporter, April 20, 2012, retrieved July 23, 2012

- ↑ Nussbaum, Paul (May 13, 2012). "N.J. to contribute to proposed Amtrak tunnel". The Philadelphia Enquier. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- 1 2 Magyar, Mark J. (October 21, 2013). "NJ FACES HEFTY PRICETAG FOR RAIL TUNNEL, TRANSPORTATION PROJECTS". NJ Spotlight. Retrieved November 24, 2013.

- 1 2 Pillets, Jeff (February 28, 2011), "State wants refund for $161.9M tunnel insurance", The Record pages =, retrieved March 14, 2011

- ↑ Higgs, Larry (December 1, 2013). "@Issue: Sharing of rail tunnel design work to aid transition from ARC to Gateway project Sharing of rail tunnel design work to aid transition from ARC to Gateway project". Asbury Park Press. Retrieved March 20, 2014.

- 1 2 Marritz, Ilya (September 28, 2012). "Sen. Schumer: Fast Action Needed for New Amtrak Tunnel". Transportation Nation. Retrieved October 3, 2012.

- ↑ Rouse, Karen (December 6, 2012). "Amtrak asks Congress for emergency funding for flood protection". The Record. Retrieved November 12, 2012.

- ↑ Goldmark, Alex (December 13, 2012). "Amtrak asks for subsidies in wake of Hurricane Sandy". Transportation Nation. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Testimony of Joseph H. Boardman...Hearing "Superstorm Sandy: the Devasting Impact on the Nation's Largest Transportation Systems "" (PDF). Amtrak. December 6, 2012. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- ↑ "President Obama signs $50B Sandy relief bill". The Star-Ledger. Associated Press. January 29, 2013. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- ↑ "Construction begins to preserve possible pathway of new train tunnels into penn station new york" (PDF). Amtrak. September 13, 2013. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/12/nyregion/corporation-to-oversee-new-hudson-rail-tunnel-with-us-and-amtrak-financing-half.html?_r=0

- ↑ http://www.northjersey.com/news/latest-plan-for-hudson-rail-tunnel-draws-questions-about-cost-accountability-1.1454391

- ↑ Prout, H.G. (September 14, 1902). "The Pennsylvania's Great Hudson River Tunnel". The New York Times. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- 1 2 Cudahy, Brian J. (2002). Rails Under the Mighty Hudson (2nd ed.). New York: Fordham University Press. ISBN 0-8232-2190-3. OCLC 48376141.

- ↑ "Newark Adopts Plans for New Rail Station; How Newark Railroad Station Will Look". The New York Times. May 14, 1931. Retrieved February 21, 2011.

- ↑ "Newark Dedicates its New Terminal; Railroad Station, Centre Link in $42,000,000 Project, Is Opened to the Public". The New York Times. March 24, 1935. Retrieved February 21, 2011.

- ↑ "New Station Open for Hudson Tubes". The New York Times. June 20, 1937. p. 1. Retrieved February 18, 2011.

- ↑ Karnoutsos, Carmela; Shalhoub, Patrick (2007). "Exchange Place". Jersey City Past and Present. New Jersey City University. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- 1 2 "Penn Station". New York Architecture Images – gone. nyc-architecture.com. Retrieved February 18, 2011.

- ↑ French, Kenneth (2002). Images of America:Railroads of Hoboken and Jersey City. USA: Arcadia Publishing. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-7385-0966-2.

- ↑ Pinkston, Elizabeth (2003). "A Brief History of Amtrak." The Past and Future of U.S. Passenger Rail Service. (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Congressional Budget Office)

- ↑ "A Brief History of Conrail". Consolidated Rail Corporation. 2003. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ↑ "Conrail, The Consolidated Rail Corporation". American-Rails.com. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ↑ Pulley, Brett (February 10, 1996). "Crash on New Jersey Transit;Agency Had Enviable Safety Record". The New York Times. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- 1 2 Hanley, Robert (September 10, 1991). "Hoboken-Newark Rail Link Opens as Part of Multimillion-Dollar Expansion". The New York Times. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- 1 2 Chen, David W. (December 8, 1996). "All Aboard for New York, if There's Parking Near the Train". The New York Times. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- 1 2 Hanley, Robert (May 1, 1991). "New Jersey to Add Trains to Midtown". The New York Times. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ↑ Sullivan, John (June 2, 2002). "New Jersey's Amtrak Blues". The New York Times. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ↑ "By Way of Jersey". The New York Times. September 4, 1910. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ↑ "PATH Rail History". Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ↑ "PATH map". Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ↑ Editorial (November 17, 2007). "Time to Move on Hudson Tunnel". The New York Times. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ↑ "Transit Friendly Development". Voorhees Transportation Center/Rutgers University. May 2009. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ↑ PANYNJ, "History Across the Hudson", The Star Ledger, retrieved March 15, 2011

- ↑ "Port Authority Bus Terminal History". Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ↑ "New Report and Website Offer Speedier Bus Commute Across the Hudson River Report calls for Port Authority to prioritize bus trips for 100 million annual passengers". Tri-state Transportation Campaign. May 14, 2009. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ↑ Chernetz, Janna (April 28, 2011). "NJ Transportation Funding Plan Would Shortchange Bus Riders". Mobilizing the Region. Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- ↑ Grossman, Andrew (April 19, 2011), "Bus Terminal Hits Limit", The Wall Street Journal, retrieved April 29, 2011

- ↑ Duane, Tom (January 20, 2011), letter to Christopher Ward, Director PANYNJ, retrieved December 3, 2011

- ↑ Boburg, Shawn; Rouse, Karen (October 2, 2011), "Cut in toll hike killed funds for $800M garage, PA says", The Record, retrieved December 3, 2011

- ↑ Boburg, Shawn (December 7, 2011), "Lawmakers urge PA to reduce bus delays", The Record, retrieved December 14, 2011

- ↑ Rouse, Karen (May 9, 2012), "NJ DOT commissioner proposes bypassing Manhattan bus terminal for some routes", The Record, retrieved May 9, 2012

- ↑ Wilshe, Brett (November 1, 2010). "With ARC tunnel scrapped, NJ Transit officials wonder what to do with $26.3 million worth of North Bergen property". NJ.com. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ↑ "Access to the Region's Core Major Investment Study Summary Report 2003" (PDF). arctunnel.com. 2003. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ↑ "MTA Pushes Back Completion of East Side Access Project until 2019". NY1. May 9, 2012. Retrieved May 9, 2012.

- ↑ New Jersey Transit (October 2008). Newark, NJ. "Access to the Region's Core: Final Environmental Impact Study." Executive Summary.

- ↑ Rassmussen, Ian (December 15, 2010). "When an Environmental Impact Statement takes a lifetime". New Urban News. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

The story of ARC began in 1995 with the start of a "Major Investment Study" that reviewed 137 alternative transportation improvements that would get commuters from central and northern New Jersey out of their cars, and into Manhattan faster, cheaper, and with less harm to the environment. After four years of study, the list was narrowed down to a few finalists in 1999. From 1999 to 2003, the feasibility of each of those plans (exactly where the tracks would be laid, and how they would connect to Penn Station) was studied, and the ultimate plan ironed out. From 2003 to 2009, the final plan — two new rail tunnels leading to a new lower level of Penn Station — was the subject of an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS).

- 1 2 3 Frassinelli, Mike (November 8, 2010). "Hudson River tunnel project proposed by Amtrak, NJ Transit would take decades to complete". The Star Ledger. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- 1 2 Fleisher, Liza; Grossman, Andrew (February 8, 2011), "Amtrak's Plan For New Tunnel Gains Support", The Wall Street Journal, retrieved February 8, 2011

- 1 2 "Amtrak, NJ Transit break off talks on reviving ARC Hudson River rail tunnel", The Star-Ledger, November 12, 2010, retrieved March 7, 2011

- ↑ McGeehan, Patrick (October 7, 2010). "Christie Halts Train Tunnel, Citing Its Cost". The New York Times. Retrieved October 8, 2010.

- ↑ "Amtrak: no interest in Hudson tunnel", The Star-Ledger, November 13, 2010, retrieved March 13, 2011

- ↑ Higgs, Larry (February 8, 2011). "Amtrak plans new tunnel under Hudson River". mycentraljersey.com. Retrieved February 21, 2011.

- ↑ "Rules and Regulation" (PDF). Federal Register 74 (101): 25448. May 28, 2009. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- ↑ "The Harrison PATH Station". Daily Harrison. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ↑ "NEC INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECTS OF RELEVANCE TO NEW JERSEY" (PDF). ARP. January 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ↑ http://blog.tstc.org/2016/02/01/gateway-project-timeline-released-but-cross-hudson-capacity-relief-still-a-long-way-off/comment-page-1/#comment-736765

- 1 2 Baldwin, Zoe (January 8, 2009). "Feds Open "Portal" to Expansion of NJ Transit's Network". Mobilizing the Region. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ↑ "Code of Federal Regulations, Title 33, Volume 1". Code of Federal Regulations. U.S. Government Printing Office. July 1, 2007. pp. 616–617. Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- ↑ "High-Speed Intercity Passenger Rail (HSIPR) Program" (PDF). gov. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ↑ Copeland, Denise; Betty the Bike (June 1, 2010). "Senator Lautenberg lends his support to bike and pedestrian access on the new Portal Bridge over the Hackensack". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- ↑ "AECOM JV Bags US$18 Mln Contract For New Jersey's Portal Bridge Replacement Project – Quick Facts". RTT News. January 5, 2010. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- ↑ CHRISTOPHER MAAG. "NJ Transit gets $16M grant for rail bridge replacement". NorthJersey.com. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ↑ "$16M federal grant will help replace Portal Bridge". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ↑ "ARC Access to the Region's Core". New Jersey Transit. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ↑ Bowen, Douglas John (June 19, 2013). "Secaucus Loop idea revived, tied to Gateway Tunnel". Railway Age. Retrieved November 24, 2013.

- ↑ Rouse, Karen (April 24, 2012), "Amtrak's Gateway Proposal includes "Bergen Loop" to NYV", The Record, retrieved April 30, 2012

- ↑ "Gateway Tunnel Could Bring Direct Train Service from North Jersey to NYC". NJ Today. April 26, 2012. Retrieved July 29, 2012.

- ↑ Rife, Judy (August 31, 2014). "MTA urged to back Amtrak project 1-seat trip for Port riders to Midtown seen". Times Herald-Record. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ↑ "NJ Transit’s Response to Shifting Travel Demand in the Aftermath of September 11, 2001" (PDF). Travel Trends (New Brunswick: The Alan M. Voorhees Transportation Center) 3. Fall 2006. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

NJ TRANSIT financed a new High Density Signal system in conjunction with the Kearny Connection, Montclair Connection and Secaucus Transfer projects that allowed the total number of NJ TRANSIT and Amtrak peak period trains operating in the heavily congested NewarkPSNY corridor to increase from 18 per hour to 23. The new signal system enabled NJ TRANSIT to substantially increase its share of peak hour trains, from 11 (of theprior capacity of 18) to 17 or 18, depending on the hour, of the 23 now available. (The "New Initiatives" agreement anticipated a capacity of 25 trains during the peak hour; however, NJ TRANSIT and Amtrak, through informal agreement, have limited the maximum number of hourly moves to 23 because of the continuing need to "reverse" trains out of New York back to New Jersey to make additional runs. These "reverse moves" cross the path of inbound trains and consume one or two precious peak slots per hour into New York.

- ↑ Rubinstein, Dana (May 5, 2014). "Clock ticking on Hudson crossings, Amtrak warns". Capital. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Amtak Seeks $1.3 billion for Gateway Project and Next-Generation High-Speed Rail on NEC". Amtrak. April 4, 2011. Retrieved April 8, 2011.

- ↑ "New Jersey Breaks Ground on Nation's Largest Transit Project" (Press release). New Jersey Transit. June 8, 2009. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ↑ Wilshe, Brett (October 31, 2010). "With ARC tunnel scrapped, NJ Transit officials wonder what to do with $26.3 million worth of North Bergen property". The Jersey Journal. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ↑ Skanska to Construct Rail Tunnel in New York for USD 52 M, Approximately SEK 380 M, May 18, 2010

- ↑ Finkelstein, Alex (May 18, 2010). "Skanska Constructing $258 Million Palisades Tunnel for New Jersey Transit". Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- ↑ Frassinelli, Mike (October 16, 2012). "NJ Transit still paying price for canceled Hudson River rail tunnel". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved March 30, 2013.

- ↑ Barbara, Philip (April 26, 2009), "Planned Hudson River rail tunnel isn't perfect, but it's good", The Star-Ledger, retrieved March 6, 2011,

One previous ARC design had a new NJ Transit station below Penn Station, which would enable all train platforms to be under one roof. But geologists found softer rock formations from an ancient stream bed that would not provide the necessary structural integrity required of new construction.....But planners found they could not repeat in a built-up city what the Pennsylvania Railroad did when it built the existing tunnel 100 years ago by digging a wide trench through the west side of Manhattan. The only solution was to dig deep – low enough to avoid the historic 90-foot-deep shoreline bulkhead and the New York Subway No. 7 line's extension. From that depth and in a short distance, trains can't reliably rise to make it into Penn Station. After repeated review, it was concluded a spur from the new tunnel was impossible.

- ↑ "New York Property Information". Access to the Region's Core. PANYNJ/NJT. 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ↑ Bagli, Charles V. (December 21, 2009). "Rezoning Will Allow Railyard Project to Advance". The New York Times. Retrieved December 22, 2009.

- ↑ "MTA Finalizes Hudson Yards Deal". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. May 26, 2010. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- ↑ Sichert, Bill (March 5, 2013). "Amtrak to construct 'tunnel box' for Hudson River rail project to cross Manhattan development". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- ↑ Samtani, HIten (February 26, 2013). "Related, Amtrak to construct rail tunnel between Manhattan and NJ". The Real Deal. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- ↑ Cuozzo, Steve (February 26, 2013). "Fed money keeps rail tunnel alive". The New York Post. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- ↑ "Second Trans-Hudson Tunnel Gets Some Real Money". Transportation Nation. WNYC. May 30, 2013. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- ↑ Hawkins, Andrew (May 30, 2013). "Hudson train tunnel project gets kickstart". Crain's. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ↑

- ↑ Environmental Assessment for Construction of a Concrete Casing in the Hudson Yards, New York, New York, Federal Railroad Administration, March 2013

- ↑ "Contract awarded for New York rail tunnel". Construction Index. September 7, 2013. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- ↑ HIggs, Larry (September 1, 2014). "Amtrak: New tunnels needed after Sandy damage". Asbury Park Press. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ↑ Maag, Christopher (September 21, 2014). "Signs of life stir for rail tunnel under Hudson". The Record. Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- ↑ "11th Avenue viAduCt OveR LiRR YARd WeSt 30th tO WeSt 33Rd StReetS" (PDF). NYC DOT. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Rehabilitation of 11th Avenue Viaduct Over LIRR/Amtrak" (PDF). Mueser Rutledge Consulting Engineers. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ↑ Gould, Jessica (July 24, 2013). "City Council Limits Lease on Madison Square Garden, Makes Way for a New Penn Station". WNYC. Retrieved November 24, 2013.

- ↑ "Madison Square Garden told to move". The New York Times. July 25, 2013. Retrieved November 24, 2013.

- ↑ Smith, Stephen Jacob (August 13, 2013). "Vanity Project: Why Fancy Architecture Won’t Save Penn Station". The New York Observer. Retrieved November 24, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Jaffee, Eric (December 22, 2011), "Can Amtrak Afford Its New NYC Home?", Atlantic Monthly, retrieved December 28, 2011

- 1 2 Editorial (February 23, 2010). "Moynihan Station, Finally?". The New York Times. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- ↑ Grynbaum, Micheal M. (October 18, 2010). "The Joys and Woes of Penn Station at 100". The New York Times. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ↑ Blumenthal, Sidney (March 14, 1994). "To the Pennsylvania Station". The New York. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- ↑ Lueck, Thomas J. (November 11, 1999). "A $60 Million Step Forward In Rebuilding Penn Station". The New York Times. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- ↑ "No. 7 Subway Extension – Hudson Yards Rezoning and Development Program" (PDF). nyc.gov. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- ↑ "A Message from the President of Moynihan Station Development Corporation". Empire State Development. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- ↑ Michaelson, Juliette (February 16, 2010). "Moynihan Station Awarded Federal Grant" (PDF). Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- ↑ Smerd, Jeremy (October 11, 2010). "Hotel, big retail eyed for Moynihan Station". Crains New York. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- ↑ "Governor Cuomo Seeks Federal Funds for High-Speed Rail Projects" (Press release). Governor's Press Office. April 4, 2011. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- ↑ "Work to begin on massive Penn Station expansion". Long Island Business News. Associated Press. May 9, 2012. Retrieved May 9, 2012.

- ↑ Boburg, Shawn (May 8, 2012), "New Amtrak station to relieve rush-hour crowds at Penn Station in first phase of project", The Record, retrieved May 14, 2012

- ↑ "Pennsylvania Station, New York Terminal Service Plant, 250 West Thirty-first Street, New York, New York County, NY". HAER. Retrieved November 25, 2014.

…constructed as an integral component of the original Pennsylvania Station complex and served as a power generation and control center for the station, its tracks and signal systems. the facade was designed by McKim Mead & White to complement the exterior of the Pennsylvania Station. While much of the original service equipment has been dismantled or abandoned, some of the original power distribution equipment is still in use...

- ↑ "PENN 2023 Envisioning a new Penn Station, the next Madison Square Garden, and the future of west Midtown" (PDF). Regional Plan Association. October 17, 2013.

- ↑ "Midtown block would likely get razed for Gateway plan". Local news. February 17, 2011. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ↑ Higgs, Larry (October 7, 2014). "Why Amtrak would have to buy $400M in NYC real estate to build new Hudson tunnel". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ↑ Maag, Christopher (January 17, 2015). "Hudson River train tunnel hinges on pricey plan". The Record. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ↑ Maag, Christopher. "N.Y.C. shrine to saint complicates Amtrak station plan". NorthJersey.com.

- ↑ "Critical Infrastructure Needs on the Northeast Corridor" (PDF). Northeast Corridor Infrastructure and Operations Advisory Commission. January 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ↑ Frassinelli, Mike (May 9, 2011), "Feds steer $450M to N.J. for high-speed rail", The Star Ledger, retrieved May 13, 2011

- ↑ Thorbourne, Ken (May 9, 2011), "Amtrak to receive nearly $450 million in high speed rail funding", The Jersey Journal, retrieved May 13, 2011

- ↑ McGeehan, Patrick (May 9, 2011), "Florida's rejected rail funds flow north", The New York Times, retrieved May 13, 2011

- ↑ Frassinelli, Mike (July 16, 2011). "House passes bill that would divert money from electrical upgrades on N.J. Northeast". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved July 16, 2011.

- 1 2 "House Vote Jeopardizes Key Northeast Rail Projects". Back on Track: Northeast. The Business Alliance for Northeast Mobility. July 20, 2011. Retrieved July 21, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Schned, Dan (August 24, 2011). "U.S. DOT Obligates $745 Million to Northeast Corridor Rail Projects". America 2050. Retrieved November 24, 2011.

- ↑ Frassinelli, Mike (September 25, 2012). "Amtrak train looks to break U.S. speed record in Northeast Corridor test". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved December 17, 2012.

- ↑ Sheehan, Rebecca (September 26, 2013). "Amtrak tests of Acela express train at 165 mph will not affect commuters". New Jersey Newsroom. Retrieved November 24, 2013.

- ↑ "Dedication of plaque commemorating high speed rail in America" on the National Capital Land Transportation Committee's website

- ↑ Wong, Kevin (September 22, 2007). "High speed rail commemorative plaque in Princeton Junction station". Retrieved November 24, 2013.

- ↑ Paulsen, Monte (June 2009). "Off the Rails How Canada fell from leader to laggard in high-speed rail, and why that needs to change". The Walrus. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- ↑ Vantuono, William C (June 11, 2013). "Amtrak sprints toward a higher speed future". Railway Age. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- ↑ "HAROLD interlocking (New York City)". wikimapia.org. Retrieved May 13, 2011.

- ↑ "Maloney Hails Federal Grant to Ease Amtrak Delays in NYC, Spur High-Speed Rail in NE Corridor – $294.7 Million Grant to Improve "Harold Interlocking", a Delay-Plagued Junction For Trains in the NE Corridor". May 9, 2011. Retrieved May 13, 2011.

- ↑ Colvin, Jill (May 9, 2011). "New York Awarded $350 Million for High-Speed Rail Projects". DNAinfo.com. Retrieved May 13, 2011.

- ↑ Bernstein, Andrea (February 4, 2011). "City finally puts $$ behind subway to New Jersey". Transportation Nation. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

- ↑ New York City Economic Development Commission (February 2, 2011). "No. 7 Line Extension to Secaucus Consultant Services" (PDF). scribd.com. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

- ↑ "N.Y. mayor Bloomberg supports extending No. 7 subway into N.J.", The Star-Ledger, October 26, 2011, retrieved November 22, 2011

- ↑ Higgs, Larry (November 19, 2011), "Obama expected to OK $15M for tunnel project between Secaucus and New York – Amtrak tunnel vs. extended subway to Secaucus showdown likely", Asbury Park Press, retrieved November 23, 2011

- ↑ Haughney, Christine (April 3, 2012), "MTA Chief rules out subway line to New Jersey", The New York Times, retrieved April 4, 2012

- ↑ Frasinelli, Mike (April 10, 2013). "Plan to extend No. 7 subway from NYC to New Jersey could be back on track". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved April 10, 2013.

- ↑ Rouse, Karen (April 10, 2013). "Report: Extending NY No. 7 subway line to Secaucus would accommodate commuter demand". The Record. Retrieved April 10, 2013.

- ↑ Gottesman, Jerry; Spinola, Steven (November 4, 2013). "Let’s extend the 7 train to Secaucus After the far West Side, the next stop on the 7 should be across the river". Daily News. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ↑ "AN ASSEMBLY RESOLUTION supporting the extension of the New York City IRT Flushing Line into the State of New Jersey." (PDF). ASSEMBLY RESOLUTION No. 168 STATE OF NEW JERSEY 215th LEGISLATURE. New Jersey Legislature. May 13, 2013. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- ↑ Brenzel, Kathryn (November 26, 2013). "Committee green lights expansion of NYC subway to Hoboken". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

External links

- Project map on Flickr

- Track map of Gateway Project track connections in New York

- "Amtrak National Facts". Amtrak. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- "Amtrak Fact Sheet, Fiscal Year 2012 State of New Jersey" (PDF). Amtrak. Retrieved November 24, 2013.

- "Amtrak Fact Sheet, Fiscal Year 2012 State of New York" (PDF). Amtrak. Retrieved November 24, 2013.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||