1976 Summer Olympics

| |

| Host city | Montreal, Quebec, Canada |

|---|---|

| Nations participating | 92 |

| Athletes participating | 6,084 (4,824 men, 1,260 women) |

| Events | 198 in 21 sports |

| Opening ceremony | July 17 |

| Closing ceremony | August 1 |

| Officially opened by | Queen Elizabeth II |

| Athlete's Oath | Pierre St.-Jean |

| Judge's Oath | Maurice Fauget |

| Olympic Torch |

Stéphane Préfontaine Sandra Henderson |

| Stadium | Olympic Stadium |

The 1976 Summer Olympics, officially called the Games of the XXI Olympiad (French: Les XXIes olympiques d'été), was an international multi-sport event in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, in 1976; the first Olympic Games hosted by Canada. Montreal was awarded the rights to the 1976 Games on May 12, 1970, at the 69th IOC Session in Amsterdam, over the bids of Moscow and Los Angeles. Calgary and Vancouver would later host Winter Olympic Games in Canada. It is so far the only Summer Olympic Games to be held in Canada.

Most sovereign African, and a few other, nations boycotted the Montreal Games when the International Olympic Committee (IOC) would not support, as had other international sporting organizations, the banning from competition of those countries whose athletes had participated in sporting events in South Africa as long as apartheid continued. The New Zealand rugby team had been touring South Africa during apartheid and were excluded from international sporting events due to implementation of the anti-apartheid policy.

Host city selection

The vote occurred on May 12, 1970, at the 69th IOC Session in Amsterdam, Netherlands. While Los Angeles and Moscow were viewed as the favorites given that they represented the world's two main powers, many of the smaller countries supported Montreal as an underdog and as a politically neutral site for the games. Los Angeles was eliminated after the first round and Montreal won in the second round. Moscow would go on to host the 1980 Summer Olympics and Los Angeles the 1984 Summer Olympics. One blank vote was cast in the second and final round.[1][2][3]

Toronto made a third attempt for the Olympics and failed to get the support of the Canadian Olympic Committee, who selected Montreal instead.[4]

| 1976 Summer Olympics bidding results[3] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | Country | Round 1 | Round 2 | |||

| Montreal | | 25 | 41 | |||

| Moscow | | 28 | 28 | |||

| Los Angeles | | 17 | — | |||

Organization

Robert Bourassa, then the Premier of Quebec, first asked Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau to advise Canada's monarch, Elizabeth II, to attend the opening of the games. However, Bourassa later became unsettled about how unpopular the move might be with sovereigntists in the province, annoying Trudeau, who had already made arrangements.[5] The leader of the Parti Québécois at the time, René Lévesque, sent his own letter to Buckingham Palace, asking the Queen to refuse her prime minister's request, though she did not oblige Lévesque as he was out of his jurisdiction in offering advice to the Sovereign.[6]

Opening Ceremony

The Opening Ceremony of the 1976 Summer Olympic Games was held on Saturday, July 17, 1976 at the Olympic Stadium in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, in front of an audience of some 73,000 in the stadium, and an estimated half billion watching on television.[7]

The ceremony marked the opening of the Games of the XXI Olympiad, the first Olympics ever held in Canada (the country would later host the 1988 Olympic Winter Games in Calgary and the 2010 Olympic Winter Games in Vancouver).

Following an air show by the Royal Canadian Air Force’s Snowbirds flying squad in the sunny skies above the stadium, the ceremony officially began at 3:00 pm with a trumpet fanfare and the arrival of Queen Elizabeth II, Queen of Canada.[8] The Queen was accompanied by Michael Morris, Lord Killanin, President of the International Olympic Committee, and was greeted to an orchestral rendition of ‘O Canada’, an arrangement that for many years later would be used in schools across the country as well as in the daily sign off of the CBC’s broadcast.[9]

The Queen also entered the Royal Box with her consort, Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, and her son, Prince Andrew (her daughter, Princess Anne, was a competitor for the team from Great Britain). She joined a number of Canadian and Olympic dignitaries, including: Jules Léger, Governor General of Canada, and his wife, Gabrielle; Canadian Prime Minister, Pierre Trudeau and wife, Margaret; Robert Bourassa, Premier of the Province of Quebec; Roger Rousseau, chief of the Montreal Olympic Organizing Committee (COJO); Sheila Dunlop, Lady Killanin, wife of the IOC President; Mayor of Montreal, Jean Drapeau, and his wife, Marie-Claire.

The parade of athletes began moments later with the arrival of the Greek team and concluded with the entrance of the Canadian team some time later. All other teams entered the stadium according to French alphabetical order. Although they would eventually boycott the Games in the days to follow, a number of African delegations did march in the parade. Much of the music performed for the parade was arranged by Vic Vogel and was inspired by late Quebec composer, André Mathieu.[10]

Immediately following the parade, a troupe of 80 women dancers dressed in white (representing the 80th anniversary of the revival of the Olympic Games) performed a brief dance in the outline of the Olympic rings.

Following that came the official speeches, first by Roger Rousseau, head of the Montreal Olympic organizing committee, and Lord Killanin. Her Majesty was then invited to proclaim the Games open, which she did, first in French, then in English.

Accompanied by the Olympic Hymn, the Olympic flag was carried into the stadium and hoisted at the west end of the stadium. The flag was carried by eight men and hoisted by four women, representing the ten provinces and two territories (at the time) of Canada. As the flag was hoisted, an all-male choir performed an a cappella version of the Olympic Hymn.

Once the flag was unfurled, a troupe of Bavarian dancers, representing Munich, host of the previous Summer Olympics, entered the stadium with the Antwerp Flag. Following a brief dance, that flag was then passed from the Mayor of Munich to the IOC President and then to the Mayor of Montreal. Next came a presentation of traditional Québécois folk dancers. The two troupes merged in dance together to the strains of “Vive le Compagnie” and exited the stadium with the Antwerp Flag, which would be displayed at Montreal City Hall until the opening of the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow.

Three cannons were then fired, as the 80-member troupe of female dancers unfolded special crates that released doves and ribbons in the five Olympic colours.

Another trumpet fanfare announced the arrival of the Olympic Flame. The torch was carried by two 15-year-olds, Stéphane Préfontaine and Sandra Henderson, chosen as representatives of the unity within Canada’s linguistic heritage. This would also be the first time two people would light the Olympic flame, and Henderson would become only the second woman to do the honours. The duo would make a lap of the stadium and then climbed a staircase on a special dais at the center of the stadium to set the Olympic flame alight in a temporary white aluminum cauldron. The flame was later transported to a more permanent cauldron just outside the running track to burn throughout the duration of the Games. A choir then performed the Olympic Cantata as onlookers admired the Olympic flame.

Then, the ‘Youth of Canada’ took to the track to perform a colourful choreographed segment with flags, ribbons and a variety of rhythmic gymnast performers.

The flag bearers of each team then circled around the speaker’s dais as Pierre St-Jean recited the Athletes’ Oath and Maurice Forget recited the Judges’ Oath, in English and in French, with right hand over the heart and the Canadian flag clutched in the left.

Finally, a choral performance of ‘O Canada’ in both French and English marked the close of the Opening Ceremony, as the announcers concluded with a declaration of ‘Vive les Jeux de Montreal! Long Live the Montreal Games’.

The Montreal ceremony would be the last of its kind, as future Olympic ceremonies, beginning with the 1980 Moscow Games, would become more focused on theatrical, cultural and artistic presentations and less on formality and protocol.

Highlights

- At age 14, gymnast Nadia Comăneci of Romania scored seven perfect 10.0 and won three gold medals, including the prestigious All-Around. The score board could hold only 3 digits and the score was shown as 1.00. In women's gymnastics three gold medals were also won by Nellie Kim of the Soviet Union. Nikolai Andrianov of the USSR won four gold medals, including All Around, in men's gymnastics.

- Taro Aso was a member of the Japanese shooting team. 32 years later, he would be elected as the prime minister of Japan.

- The Games were opened by Elizabeth II, as head of state of Canada, and several members of the Royal Family attended the opening ceremonies. This was particularly significant, as these were the first Olympic games hosted on Canadian soil. The Queen's daughter, Princess Anne, also competed in the games as part of the British riding team.

- After a rainstorm doused the Olympic Flame a few days after the games had opened, an official relit the flame using his cigarette lighter. Organizers quickly doused it again and relit it using a backup of the original flame.

- The Israeli team walked into the stadium at the Opening Ceremonies march, wearing in their white suit like the national flag a black ribbon in commemoration of the 1972 Munich massacre.[11]

- Women's events were introduced in basketball, handball and rowing.

- Canada, the host country, finished with five silver and six bronze medals. This was the first time that the host country of the Summer Games had not won any gold medals. This feat had occurred previously only in the Winter Games – 1924 in Chamonix, France and 1928 in St. Moritz, Switzerland. This later occurred at the 1984 Winter Games in Sarajevo, Yugoslavia, and again at the 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary, Canada.

- Because of the Munich massacre, security at these games was visible, as it had been earlier in the year at the Winter games in Innsbruck, Austria.

- Viktor Saneyev of the Soviet Union won his third consecutive triple jump gold medal, while Klaus Dibiasi of Italy did the same in the platform diving event.

- Alberto Juantorena of Cuba became the first man to win both the 400 m and 800 m at the same Olympics.

- Finland's Lasse Virén repeated his 1972 double win in the 5,000 and 10,000 m runs, the first and to date only runner to successfully defend a 5,000 m win. Virén finished 5th in the marathon, thereby failing to equal Emil Zátopek's 1952 achievements.

- Hasley Crawford wins Trinidad and Tobago's first gold medal in the 100 meter dash

- Boris Onishchenko, a member of the Soviet Union's modern pentathlon team, was disqualified after it was discovered that he had rigged his épée to register a hit when there wasn't one. Because of this, the USSR modern pentathlon team was disqualified. Onischenko earned the enmity of other Soviet Olympic team members: for example, USSR volleyball team members threatened to throw him out of the hotel's window if they met him. Due to his disqualification, it was suggested that he earned the nickname of "Boris DISonish-chenko".

- Five American boxers – Sugar Ray Leonard, Leon Spinks, Michael Spinks, Leo Randolph and Howard Davis Jr. won gold medals in boxing. This has been often called the greatest Olympic boxing team the United States ever had, and, out of the five American gold medalists in boxing, all but Davis went on to become professional world champions.

- Princess Anne of the United Kingdom was the only female competitor not to have to submit to a sex test.[12] She was a member of her country's equestrian team.

- Japanese gymnast Shun Fujimoto performed on a broken right knee, and helped the Japanese team win the gold medal for the team championship. Fujimoto broke his leg on the floor exercise, and due to the closeness in the overall standings with the USSR, he hid the extent of the injury. With a broken knee, Fujimoto was able to complete his event on the rings, performing a perfect triple somersault dismount, maintaining perfect posture. He scored a 9.7 thus securing gold for Japan. Years later, when asked if he would do it again, he stated bluntly "No, I would not."[13]

- The East German women's swimming team won all but two gold medals.

- The U.S. men's swimming team won all but one gold medal.

- Luann Ryon won the women's Archery gold for the USA; Ryon had never before competed at the international level.

- U.S. track and field athlete Bruce Jenner won the gold medal for decathlon, setting a world record of 8,634 points.

- Alex Oakley, the Canadian race walker, became the oldest track and field athlete to compete at the Olympic Games. He was aged 50, and taking part in his fifth Olympics.

- The New Zealand men's national field hockey team beat Australia to win gold, becoming the first non-Asian/European team to win the gold medal in hockey. It is also the first Olympic games in which hockey was played on artificial turf.

- American George Mount placed 6th in the cycling road race. It was the best result in Olympic cycling for America since WW II. Mount's result helped America's revitalisation in international cycling competition.

- The Polish Men's Volleyball team came back from being down 2 sets against the USSR to win the Olympic Gold Medal

- Twenty-year-old Morehouse College student Edwin Moses sets a new world record in the 400m hurdles, less than a year after taking up the event. He is also America's only male individual track gold medalist.

- Thomas Bach of West Germany won a gold medal in the team foil event in fencing. He would later become IOC President.

Venues

Montreal Olympic Park

- Olympic Stadium – Opening/Closing ceremonies, Athletics, Football (final), Equestrian (jumping team final)

- Olympic Pool – Diving, Modern pentathlon (swimming), Swimming, Water polo (final)

- Olympic Velodrome – Cycling (track), Judo

- Montreal Botanical Garden – Athletics (20 km walk), Modern pentathlon (running)

- Maurice Richard Arena – Boxing, Wrestling

- Centre Pierre Charbonneau – Wrestling

- Olympic Village – Athletes' residence

Venues in Greater Montreal

- Olympic Basin, Île Notre-Dame – Canoeing, Rowing

- Claude Robillard Centre – Handball, Water polo

- Centre Étienne Desmarteau – Basketball

- St. Michel Arena – Weightlifting

- Paul Sauvé Centre – Volleyball

- Montreal Forum – Basketball (final), Boxing, Gymnastics, Handball, Volleyball

- Mount Royal Park – Cycling (individual road race)

- Quebec Autoroute 40 – Cycling (road team time trial)

- Streets of Montreal – Athletics (marathon)

- Winter Stadium, Université de Montréal – Fencing, Modern pentathlon (fencing)

- Molson Stadium, McGill University – Field hockey

Venues outside Montreal

- Olympic Shooting Range, L'Acadie – Modern pentathlon (shooting), Shooting

- Olympic Archery Field, Joliette – Archery

- Olympic Equestrian Centre, Bromont – Equestrian (all but jumping team), Modern pentathlon (riding)

- Pavilion de l'éducation physique et des sports de l'Université Laval, Quebec City, Quebec – Handball preliminaries

- Sherbrooke Stadium, Sherbrooke, Quebec – Football preliminaries

- Sherbrooke Sports Palace, Sherbrooke, Quebec – Handball preliminaries

- Portsmouth Olympic Harbour, Kingston, Ontario – Sailing

- Varsity Stadium, Toronto, Ontario – Football preliminaries

- Lansdowne Park, Ottawa, Ontario – Football preliminaries

Medals awarded

The 1976 Summer Olympic programme featured 198 events in the following 21 sports:

|

|

Calendar

- All times are in Eastern Daylight Time (UTC-4)

| ● | Opening ceremony | Event competitions | ● | Event finals | ● | Closing ceremony |

| Date | July | August | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17th Sat | 18th Sun | 19th Mon | 20th Tue | 21st Wed | 22nd Thu | 23rd Fri | 24th Sat | 25th Sun | 26th Mon | 27th Tue | 28th Wed | 29th Thu | 30th Fri | 31st Sat | 1st Sun | |

| Archery | ● ● | |||||||||||||||

| Athletics | ● ● | ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● |

||||||||

| Basketball | ● | ● | ||||||||||||||

| Boxing | ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● |

|||||||||||||||

| Canoeing | ● ● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● |

||||||||||||||

| Cycling | ● | ● | ● | ● ● | ● | |||||||||||

| Diving | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||||

| Equestrian | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||||

| Fencing | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||

| Field hockey | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Football (soccer) | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Gymnastics | ● | ● | ● ● | ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● ● |

|||||||||||

| Handball | ● ● | |||||||||||||||

| Judo | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||

| Modern pentathlon | ● ● | |||||||||||||||

| Rowing | ● ● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● |

||||||||||||||

| Sailing | ● ● ● ● ● |

● | ||||||||||||||

| Shooting | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● ● | ● | ||||||||||

| Swimming | ● ● | ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● |

● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● |

|||||||||

| Volleyball | ● ● | |||||||||||||||

| Water polo | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Weightlifting | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||

| Wrestling | ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● |

||||||||||||||

| Total gold medals | 4 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 14 | 11 | 26 | 21 | 10 | 12 | 11 | 8 | 17 | 36 | 1 | |

| Ceremonies | ● | ● | ||||||||||||||

| Date | 17th Sat | 18th Sun | 19th Mon | 20th Tue | 21st Wed | 22nd Thu | 23rd Fri | 24th Sat | 25th Sun | 26th Mon | 27th Tue | 28th Wed | 29th Thu | 30th Fri | 31st Sat | 1st Sun |

| July | August | |||||||||||||||

Medal count

These are the top ten nations that won medals at the 1976 Games. Canada placed 27th with only 11 medals in total — none of them being gold. Canada remains the only host nation of a Summer Olympics that did not win at least one gold medal in its own games. It also did not win any gold medals at the 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary. However, Canada went on to win the most gold medals at the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver.

East Germany, surpassed all expectations for a middle-sized nation by finishing 2nd. However, the GDR’s achievements were later fundamentally undermined by the expose of a serious and systematic scheme of doping by the East German sporting authorities.[14] The GDR’s medals tally would have been much smaller without this planned, state-led programme of cheating.

| Rank | Nation | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | | 49 | 41 | 35 | 125 |

| 2 | | 40 | 25 | 25 | 90 |

| 3 | | 34 | 35 | 25 | 94 |

| 4 | | 10 | 12 | 17 | 39 |

| 5 | | 9 | 6 | 10 | 25 |

| 6 | | 7 | 6 | 13 | 26 |

| 7 | | 6 | 9 | 7 | 22 |

| 8 | | 6 | 4 | 3 | 13 |

| 9 | | 4 | 9 | 14 | 27 |

| 10 | | 4 | 5 | 13 | 22 |

| 27 | | 0 | 5 | 6 | 11 |

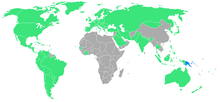

Participating National Olympic Committees

Four nations made their first Summer Olympic appearance in Montreal: Andorra (which had its overall Olympic debut a few months before in Innsbruck Winter Olympics), Antigua and Barbuda (as Antigua), Cayman Islands, and Papua New Guinea.

Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of athletes from each nation that competed at the Games.

-

Guyana,

Guyana,  Mali and

Mali and  Swaziland also took part in the Opening Ceremony, but later join to the Congolese-led boycott and withdrew from competition.[15]

Swaziland also took part in the Opening Ceremony, but later join to the Congolese-led boycott and withdrew from competition.[15]

Non-participating National Olympic Committees

Twenty-eight countries boycotted the Games[16] due to the refusal of the IOC to ban New Zealand, after the New Zealand national rugby union team had toured South Africa earlier in 1976.[17][18] The boycott was led by Congo’s official Jean Claude Ganga. Some of the boycotting nations (including Morocco, Cameroon and Egypt) had already participated, however, the teams withdrew after the first day. Senegal and Ivory Coast were the only sovereign countries in Africa that did not boycott the event. Elsewhere, both Iraq and Guyana also opted to join the Congolese-led boycott. South Africa had been banned from the Olympics since 1964 due to its apartheid policies.

Republic of China boycott

An unrelated boycott of the Montreal Games was the name issue between the Republic of China (ROC) and the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The ROC team withdrew from the games when Canada's Liberal government under Pierre Elliott Trudeau told it that the name "Republic of China" was not permissible at the Games because Canada had officially recognized the PRC. Canada attempted a compromise by allowing the ROC the continued use of its national flag and anthem in the Montreal Olympic activities; the ROC refused. Later in November 1976, the IOC recognized the PRC as the only recognized name of any Olympic activities representative of any Chinese government. In 1979 the IOC established in the Nagoya Resolution that the PRC agreed to participate in IOC activities if the Republic of China was referred to as "Chinese Taipei". Another boycott would occur before the ROC would accept the provisions of the 1979 Resolution although the reason that so many other countries boycotted were not all the same as the ROC.

| Non-participating National Olympic Committees |

|---|

Legacy

The legacy of the Montreal Olympics is complex. Many citizens regard the Olympiad as a financial disaster for the city as it faced debts for 30 years after the Games had finished. The retractable roof of the Olympic Stadium never properly worked and on several occasions has torn, prompting the stadium to be closed for extended periods of time for repairs. The failure of the Montreal Expos baseball club is largely blamed on the failure of the Olympic Stadium to transition into an effective and popular venue for the club - given the massive capacity of the stadium, it often looked unimpressive even with regular crowds in excess of 20,000 spectators.

1976 also marks the year the Parti Québécois was elected, driving inter-provincial migration out of the province and coinciding with the beginning of a significant era of depopulation in the city of Montreal coupled with loss of economic prominence to Toronto.

Montreal’s economy was also changing much like other industrial cities in the Great Lakes and Saint Lawrence River region of North America. In sum, numerous political, socio-cultural and economic changes affected the city at around the same time as the Olympics that would result in stalled growth and give the appearance of decline. That said, many of these factors existed prior to the Olympics and continued to have an effect on Montreal’s growth and relative importance many years afterwards. It’s not definitively proven that the Montreal Olympics played a specific role in that decline.

The relative benefits of the Olympics were defined differently to the Olympics of the 21st century, as was the method they were financed and presented to the public.

The Quebec provincial government took over construction when it became evident in 1975 that work had fallen far behind schedule. Work was still ongoing just weeks before the opening date, and the tower was not built. Mayor Jean Drapeau had confidently predicted in 1970 that “the Olympics can no more have a deficit than a man can have a baby”, but the debt racked up to a billion dollars that the Quebec government mandated the city pay in full. This would prompt cartoonist Aislin to draw a pregnant Drapeau on the telephone saying, "Allo, Morgentaler?" in reference to a Montreal abortion provider.

The Olympic Stadium was designed by French architect Roger Taillibert. It is often nicknamed “The Big O” as a reference to both its name and to the doughnut-shape of the permanent component of the stadium’s roof, though “The Big Owe” has been used to reference the astronomical cost of the stadium and the 1976 Olympics as a whole. It has never had an effective retractable roof, and the tower (called the Montreal Tower) was completed only after the Olympic Games were over. In December 2006 the stadium’s costs were finally paid in full.[19] The total expenditure (including repairs, renovations, construction, interest, and inflation) amounted to C$1.61 billion. Today, despite its huge cost, the stadium is devoid of a major tenant, after the Montreal Alouettes left in 1998 and the Montreal Expos moved in 2005.

One of the streets surrounding the Olympic Stadium was renamed to honor Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the Olympics.

The boycott by African nations over the inclusion of New Zealand, whose rugby team had played in South Africa that year, was a contributing factor in the massive protests and civil disobedience that occurred during the 1981 Springbok Tour of New Zealand. Official sporting contacts between South Africa and New Zealand did not occur again until after the fall of apartheid.

Australia’s failure to win a gold medal led the country to create the Australian Institute of Sport.

With Montreal’s own Canadiens winning the Stanley Cup the following year, Canada hosting an Olympics has been seen as a good omen to the NHL team in the host city the following year.[20] A year after Calgary hosted the 1988 Winter Olympics, their Flames won the Stanley Cup.[20] The Vancouver Canucks hoped to continue this in the 2011 Stanley Cup Finals, a year after Vancouver hosted the 2010 Winter Olympics.[20][21] However, they ended up losing to the Boston Bruins.[22]

See also

- 1976 Summer Paralympics

- 1976 Winter Paralympics

- 1976 Winter Olympics

- Olympic Games celebrated in Canada

- Olympic Games with significant boycotts

- 1976 Summer Olympics – Montreal – African boycott

- 1980 Summer Olympics – Moscow – United States-led boycott

- 1984 Summer Olympics – Los Angeles – Soviet-led boycott

- Summer Olympic Games

- Olympic Games

- International Olympic Committee

- List of IOC country codes

- Use of performance-enhancing drugs in the Olympic Games — 1976 Montreal

- Corridart

Notes

- ↑ http://www.aldaver.com/votes.html

- ↑ Stuart, Charles Edward (2005). Never Trust a Local: Inside the Nixon White House. Algora Publishing. p. 160.

- 1 2 "Past Olympic host city election results". GamesBids. Archived from the original on March 17, 2011. Retrieved March 17, 2011.

- ↑ http://www.thestar.com/news/gta/2015/07/24/toronto-has-made-5-attempts-to-host-the-olympics-could-the-sixth-be-the-winner.html

- ↑ Heinricks, Geoff (2000). "Trudeau and the Monarchy". Canadian Monarchist News. Winter/Spring 2000–01 (Toronto: Monarchist League of Canada, published 2001).

- ↑ "Politics > Parties & Leaders > René Lévesque's Separatist Fight > René, The Queen and the FLQ". CBC. Retrieved July 5, 2009.

- ↑ City of Montreal website (in French) http://ville.montreal.qc.ca/portal/page?_pageid=3056,3514006&_dad=portal&_schema=PORTAL

- ↑ Video of the ceremony http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ZqPL9FOHI0

- ↑ CBC sign-on, sign-off video from 1987 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qqmXyWbrD0I

- ↑ Arthur Takacs’ published memoirs http://www.montrealolympics.com/takac.php

- ↑ Video on YouTube

- ↑ This has often been reported as fact as early as 1977, but never verified by the Olympics authorities. For example, see Young, Dick. "THE BARBIE DOLL SOAP OPERA". New York Daily News. reprinted in Best Sports Stories 1977. p. 47. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

I have it on the strongest authority that Princess Anne did not have to submit to a sex test to compete in the Olympic Equestrian events.

- ↑ "Fujimoto caps Japanese success", BBC, September 29, 2000

- ↑ "Doping Scandal of East Germany in the 1970s". YouTube.

- ↑ Complete official IOC report. Part I (PDF). Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ↑ "Africa and the XXIst Olympiad" (PDF). Olympic Review. IOC. 1976. Retrieved April 3, 2006.

- ↑ "The Montreal Olympics boycott | NZHistory.net.nz, New Zealand history online". Nzhistory.net.nz. Archived from the original on 16 October 2008. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ↑ "BBC ON THIS DAY | 17 | 1976: African countries boycott Olympics". London: News.bbc.co.uk. July 17, 1976. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ↑ CBC News (December 19, 2006). "Quebec’s Big Owe stadium debt is over". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- 1 2 3 "Olympic history in Canucks' corner". NHL.com. National Hockey League. May 28, 2011. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- ↑ Morris, Jim (April 10, 2011). "Canucks look to re-write playoff history". Yahoo! Sports. Canadian Press. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ↑ cbc.ca

References

- "Montreal 1976". Olympic.org. International Olympic Committee.

- "Results and Medalists". Olympic.org. International Olympic Committee.

Further reading

- Paul Charles Howell. The Montreal Olympics: An Insider's View of Organizing a Self-Financing Games (2009)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 1976 Summer Olympics. |

- "Montreal 1976". Olympic.org. International Olympic Committee.

- 1976: African countries boycott Olympics

- Official site by senior members of the Montreal Games Organizing Committee

| Preceded by Munich |

Summer Olympic Games Montreal XXI Olympiad (1976) |

Succeeded by Moscow |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|