Insect mouthparts

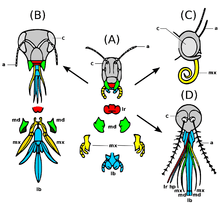

Insects exhibit a range of mouthparts, adapted to particular modes of feeding. The earliest insects had chewing mouthparts. Specialization has mostly been for piercing and sucking, although a range of specializations exist, as these modes of feeding have evolved a number of times (for example, mosquitoes (which are flies) and aphids (which are true bugs) both pierce and suck, however female mosquitoes feed on animal blood whereas aphids feed on plant fluids). In this page, the individual mouthparts are introduced for chewing insects. Specializations are generally described thereafter.

Evolution

Like most external features of arthropods, the mouthparts of hexapoda are highly derived. Insect mouthparts show a multitude of different functional mechanisms across the wide diversity of species considered insects. Significant homology is conserved, with structures being formed from the same basal cell lines, and having the same evolutionary origin. On the other hand, even analogous structures may not share true homology, and are only easily comparable due to convergent evolution.

Chewing insects

Examples of chewing insects include dragonflies, grasshoppers and beetles. Some insects do not have chewing mouthparts as adults but do as larvae, such as moths and butterflies.

Mandible

_lapping_mouthparts%2C_showing_labium_and_maxillae..jpg)

Chewing insects have two mandibles, one on each side of the head. The mandibles are positioned between the labrum and maxillae. They are typically the largest mouthparts of chewing insects, being used to masticate (cut, tear, crush, chew) food items. They open outwards (to the sides of the head) and come together medially. In carnivorous chewing insects, the mandibles can be modified to be more knife-like, whereas in herbivorous chewing insects, they are more typically broad and flat on their opposing faces (e.g., caterpillars). Mandibles are moved by two sets of muscles known as the adductor muscles and abductor muscles.

In male stag beetles, the mandibles are modified to such an extent that they do not serve any feeding function, but are instead used to defend mating sites from other males. In ants, the mandibles also serve a defensive function (particularly in soldier castes). In bull ants, the mandibles are elongate and toothed, used as hunting (and defensive) appendages. In bees, which feed primarily by use of a proboscis, the primary use of the mandibles is to manipulate and shape wax, and many wasps have mandibles adapted to scraping and ingesting wood fibres.

Maxilla

Situated beneath the mandibles, paired maxillae manipulate food during mastication. Each maxilla consists of two parts as, proximal cardo, and more distal stipes. At the apex of the stipes, two lobes can be found, which are called inner lacinia and outer galea. Maxillae can have hairs and "teeth" along their inner margins. At the outer margin, the galea is a cupped or scoop-like structure, which sits over the outer edge of the labium. They also have palps placed laterally on the stipes, which are used to sense the characteristics of potential foods.

There are muscles which extends from cranium to the base of the stipes and cardo. These are responsible for the movement of the maxilla in right angled way to the head. Maxilla can also functions like mandibles or jaws even though they are not heavily sclerotized. Galea, lacinia and palps are also moveble up to some extent. Maxillae are also innervated by the sub-esopharyngeal ganglia like the mandible.

Labium

The labium is a quadrupedal structure, although it is formed from two fused secondary maxillae. It can be described as the floor of the mouth. With the maxillae, it assists manipulation of food during mastication or chewing or, in the unusual case of the dragonfly nymph, extends out to snatch prey back to the head where mandibles can eat it.[1]

Labium is located at the rear end of the structure called cibarium. The broad basal portion of labium is divided into submentum, mentum, and prementum. The prementum gives rise to a structure called legula. This consists of a inner pair of lobes called glossae and a lateral pair called paraglossae. These structures are equivalent to lacinia and galea of maxillae. The labial palps present on the sides of labium are the counterparts of maxillary palps. These are also aids in sensory function. The muscular supply to the labium is much complex, where the legula, palp and prementum can all be moved independently. The labium is innervated by the sub-esophageal ganglia.[2][3][4]

In the honey bee, the labium is elongated to form a tube and tongue, and these insects are classified as having chewing and lapping mouthparts. [5]

Hypopharynx

The hypopharynx is a somewhat globular structure, located medially to the mandibles and the maxillae. It is mostly membranous and associated with salivary glands. It assists swallowing the food. Hypopharynx divides the oral cavity in to two parts as cibarium or dorsal food pouch and ventral salivarium in to which the salivary duct opens.

Siphoning insects

This section deals only with sucking insects, not those that pierce prior to sucking. The typical example is the moths and butterflies, although as is always the case with insects, there are variations. Some moths have no mouthparts at all. All but a few adult Lepidoptera lack mandibles (the mandibulate moths have fully developed mandibles as adults), with the remaining mouthparts forming an elongated sucking tube, the proboscis.

Proboscis

One of the more defining characteristics of lepidopterans is their coiled proboscis. It is held coiled under the head when not in use. During feeding, however, it is extended to reach the nectar of flowers. The proboscis is a long tube that is formed by heavily modified maxillae, specifically the galea.

Piercing and sucking insects

A number of insect orders (or more precisely families within them) have mouthparts that pierce food items to enable sucking of internal fluids. Some are herbivorous, like aphids and leafhoppers, while others are insectivorous, like assassin bugs and mosquitoes (females only).

Proboscis

The defining feature of the order Hemiptera is the possession of mouthparts where the mandibles and maxillae are modified into a proboscis, sheathed within a modified labium, which is capable of piercing tissues and sucking out the liquids. For example, true bugs, such as shield bugs, feed on the fluids of plants. Predatory bugs such as assassin bugs have the same mouthparts, but they are used to pierce the cuticles of captured prey.

Stylet

In female mosquitoes, all mouthparts are elongated. The labium encloses all other mouthparts like a sheath. The labrum forms the main feeding tube, through which blood is sucked. Paired mandibles and maxillae are present, together forming the stylet, which is used to pierce an animal's skin. During piercing, the labium remains outside the food item's skin, folding away from the stylet. Saliva containing anticoagulants, is injected into the food item and blood sucked out, each through different tubes.

Sponging insects

Labellum

The housefly is the typical sponging insect. The labium gives the description, being articulate and possessing at its end a sponge-like labellum. Paired mandibles and maxillae are present, but much reduced and non-functional. The labium forms a proboscis which is used to channel liquid food to the oesophagus. The housefly is able to eat solid food by secreting saliva and dabbing it over the food item. As the saliva dissolves the food, the solution is then drawn up into the mouth as a liquid.

The labellum's surface is covered by minute food channels, formed by the interlocking elongate hypopharynx and epipharynx, which form a tube leading to the oesophagus. The food channel draws liquid and liquified food to the oesophagus by capillary action.