Galápagos fur seal

| Galápagos fur seal | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male, Santiago Island | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Pinnipedia |

| Family: | Otariidae |

| Subfamily: | Arctocephalinae |

| Genus: | Arctocephalus |

| Species: | A. galapagoensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Arctocephalus galapagoensis Heller, 1904 | |

| |

| Galápagos fur seal range | |

The Galápagos fur seal (Arctocephalus galapagoensis) breeds on the Galápagos Islands in the eastern Pacific, west of mainland Ecuador.

Description

Galápagos fur seals are the smallest of otariids. They have a grayish brown fur coat. The adult males of the species average 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) in length and 64 kg (141 lb) in mass. The females average 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in) in length and 28 kg (62 lb) in mass. They spend more time out of the water than almost any other seal. On average, 70% of their time is spent on land. Most seal species spend 50% of their time on land and 50% in the water.

Range and habitat

The Galápagos fur seal is endemic to the Galápagos Islands, with a single colony in northern Peru, according to the Organisation for Research and Conservation of Aquatic Animals; they live on the rocky shores of the islands, which tend to be on the west sides, leaving only to feed.

Reproduction

Galápagos fur seals live in large colonies on the rocky shores. These colonies are then divided into territories by the female seals during breeding season, which is mid-August to mid-November. Every mother seal claims a territory for herself and breeds her pup there.[2]

Maternal care

Galápagos fur seals have the lowest reproductive rate reported in seals, and it takes an unusually long time to raise seal pups to independence.[2] Females bear only one pup at a time, and she remains with her newborn for a week before leaving to feed. She then periodically returns to the pup and stays to suckle it for a few days before leaving on another hunting trip. Females recognize their own pups by smell and sound, and pups also learn to identify their mothers by the females’ “Pup Attraction Calls”.[3] Mother-pup recognition is crucial because females exclusively nurse their own pups, often violently rejecting strange pups that approach. Orphaned seal pups usually try to sneak up on sleeping or calling females to suckle, but stealing milk is not enough to sustain the pups, and they usually die within a month.[3]

Interbrood conflict

Fur seal pups rely on their mother’s milk for the first eighteen months, and weaning may be delayed for up to two or three years if conditions are poor. The result is that every year up to 23% of pups are born when an older sibling is still suckling.[4] Survival of the younger sibling greatly depends on the availability of resources. In years when there is abundant food, the mortality rate of second pups is as low as 5%, which is equivalent to the mortality rate of pups without siblings. In years when food is scarce, 80% of pups with suckling older siblings die within a month.[2] The younger sibling thus serves as an insurance in case the first sibling dies, and also provides extra reproductive value in case conditions prove better than expected. Such a bet-hedging strategy is particularly useful in Galapagos fur seals, since there is a great deal of maternal investment in raising a seal pup to independence in an environment that has great fluctuations in food.

The high level of resource uncertainty, late weaning, and potential overlap time of suckling young all lead to violent sibling rivalry and provide a good environment for studying parent-offspring conflict. From an offspring’s point of view, it would be most beneficial to continue suckling and receive more than its fair share of milk, but to the mother seal, it would pay to wean the older, more independent offspring in order to invest in the next pup.[4] Thus, studies show that 75% of mothers intervened, often aggressively, when the older sibling harassed the newborn pups. Mothers would bite or lift the older offspring roughly by its skin, which sometimes caused open wounds. Maternal aggression towards the older sibling diminishes with time after the second sibling’s birth. Even without direct aggression, older siblings may still indirectly harm their younger siblings by outcompeting them for milk. The older offspring usually suckles first and allows their younger sibling access to the mother only after it is satiated, resulting in very little milk left over for the younger pup. Thus, the younger siblings often die from starvation.[5]

During periods when there is very little prey, interbrood conflict increases. Galapagos fur seal population is drastically affected by El Nino, a period accompanied by high water temperatures and a deepening thermocline.[6] Food becomes scarce during El Nino, and thus older seals exhibit an intense aversion to weaning, causing the mother seal to neglect the younger sibling.

Feeding and predation

The Galápagos fur seal feeds primarily on fish and cephalopods. They feed relatively close to shore and near the surface, but have been seen at depths of 169 m (554 ft). They primarily feed at night because their prey is much easier to catch then.[7] During normal years, food is relatively plentiful. However, during an El Niño year, there can be fierce competition for food, and many young pups die during these years. The adult seals feed themselves before their young and during particularly rough El Niño years, most of the young seal populations will die.

The Galápagos fur seal has virtually no constant predators. Occasionally, sharks and orcas have been seen feeding on the seals, but this is very rare. Sharks and orcas are the main predator of most other seal species, but their migration paths do not usually pass the Galápagos.

Conservation

Galápagos fur seals have had a declining population since the 19th century. Thousands of these seals were killed for their fur in the 1800s by poachers. Starting in 1959, Ecuador established strict laws to protect these animals. The government of Ecuador declared the Galápagos Islands a national park, and since then no major poaching has occurred. Despite the laws, another tragic blow to their population occurred during the 1982–1983 El Niño weather event. Almost all of the seal pups died, and about 30% of the adult population was wiped out.

The population is relatively stable now and is on the rise. Since 1983 no major calamity has occurred to decrease their population significantly.

References

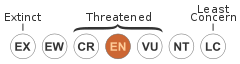

- ↑ Aurioles, D. & Trillmich, F. (IUCN SSC Pinniped Specialist Group) 2008. Arctocephalus galapagoensis. In: IUCN 2012. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.2.

- 1 2 3 Horning, M. and Trillmich, F. (1997). "Ontogeny of diving behaviour in the Galapagos fur seal". Behaviour 134 (15): 1211–1257. doi:10.1163/156853997X00133.

- 1 2 Trillmich, Fritz (1981). "Mutual Mother-Pup Recognition in Galápagos Fur Seals and Sea Lions: Cues Used and Functional Significance". Behaviour 78 (1/2): 21–42. doi:10.1163/156853981X00248.

- 1 2 Davies, N. and Krebs, J. and West, S. (2012). An Introduction to Behavioural Ecology (Fourth ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4443-3949-9.

- ↑ Trillmich, Fritz. and Wolf, Jochen (2008). "Parent–offspring and Sibling Conflict in Galápagos Fur Seals and Sea Lions". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 62 (3): 363–375. doi:10.1007/s00265-007-0423-1.

- ↑ Aurioles-Gamboa, D. and Schramm, Y. and Mesnick, S. (2004). "Galapagos Fur Seals, Arctocephalus Galapagoensis, in Mexico". Latin American Journal of Aquatic Mammals 3 (1): 77–80. doi:10.5597/lajam00051.

- ↑ Horning, M. and Trillmich, F. (1999). "Lunar Cycles in Diel Prey Migrations Exert a Stronger Effect on the Diving of Juveniles Than Adult Galapagos Fur Seals". Proceedings of the Royal Society B 266 (1424): 1127–1132. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0753.

Further reading

- MarineBio.(1999). Retrieved September 22, 2008, from http://marinebio.org/species.asp?id=293

- Randall R. Reeves, Brent S. Stewart, Phillip J. Clapham and James A. Powell (2002). National Audubon Society Guide to Marine Mammals of the World. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. ISBN 0375411410.