Fugacity

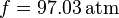

In chemical thermodynamics, the fugacity of a real gas is an effective partial pressure which replaces the mechanical partial pressure in an accurate computation of the chemical equilibrium constant. It is equal to the pressure of an ideal gas which has the same chemical potential as the real gas. For example, nitrogen gas (N2) at 0°C and a pressure of  has a fugacity of

has a fugacity of  .[1] This means that the chemical potential of real nitrogen at a pressure of 100 atm is less than if nitrogen were an ideal gas; the value of the chemical potential is that which nitrogen as an ideal gas would have at a pressure of 97.03 atm.

.[1] This means that the chemical potential of real nitrogen at a pressure of 100 atm is less than if nitrogen were an ideal gas; the value of the chemical potential is that which nitrogen as an ideal gas would have at a pressure of 97.03 atm.

Fugacities are determined experimentally or estimated from various models such as a Van der Waals gas that are closer to reality than an ideal gas. The ideal gas pressure and fugacity are related through the dimensionless fugacity coefficient  .[2]

.[2]

For nitrogen at 100 atm, the fugacity coefficient is 97.03 atm / 100 atm = 0.9703. For an ideal gas, fugacity and pressure are equal so  is 1.

is 1.

The contribution of nonideality to the chemical potential of a real gas is equal to RT ln  . Again for nitrogen at 100 atm, the chemical potential is μ = μid + RT ln 0.9703, which is less than the ideal value μid because of intermolecular attractive forces.

. Again for nitrogen at 100 atm, the chemical potential is μ = μid + RT ln 0.9703, which is less than the ideal value μid because of intermolecular attractive forces.

The fugacity is closely related to the thermodynamic activity. For a gas, the activity is simply the fugacity divided by a reference pressure to give a dimensionless quantity. This reference pressure is called the standard state and normally chosen as 1 atmosphere or 1 bar, Again using nitrogen at 100 atm as an example, since the fugacity is 97.03 atm, the activity is just 97.03 without units.

Accurate calculations of chemical equilibrium for real gases should use the fugacity rather than the pressure. The thermodynamic condition for chemical equilibrium is that the total chemical potential of reactants is equal to that of products. If the chemical potential of each gas is expressed as a function of fugacity, the equilibrium condition may be transformed into the familiar reaction quotient form (or law of mass action) except that the pressures are replaced by fugacities.

For a condensed phase (liquid or solid) in equilibrium with its vapor phase, the chemical potential is equal to that of the vapor, and therefore the fugacity is equal to the fugacity of the vapor. This fugacity is approximately equal to the vapor pressure when the vapor pressure is not too high.

The word "fugacity" is derived from the Latin for "fleetness", which is often interpreted as "the tendency to flee or escape". The concept of fugacity was introduced by American chemist Gilbert N. Lewis in 1901.[3]

Definition in terms of chemical potential

The fugacity of a real gas is formally defined by an equation analogous to the relation between the chemical potential and the pressure of an ideal gas.

or

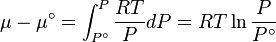

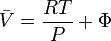

In general, the chemical potential (μ) is defined as the partial molar Gibbs free energy. However, for any pure substance it is equal to the molar Gibbs free energy, and its variation with temperature (T) and pressure (P) is given by  . At constant temperature, this expression can be integrated as a function of

. At constant temperature, this expression can be integrated as a function of  . We must also set a reference state. For an ideal gas the reference state depends only on pressure, and we set

. We must also set a reference state. For an ideal gas the reference state depends only on pressure, and we set  = 1 bar so that

= 1 bar so that

Now, for an ideal gas

Reordering, we get

This gives the chemical potential for an ideal gas in an isothermal process, with a reference state is  = 1 bar.

= 1 bar.

For a real gas, the integral  cannot be calculated because there isn't a simple expression for a real gas's molar volume. Even if using an approximate expression such as the van der Waals equation, the Redlich–Kwong or any other equation of state, it would depend on the substance being studied and would be therefore of very limited utility.

cannot be calculated because there isn't a simple expression for a real gas's molar volume. Even if using an approximate expression such as the van der Waals equation, the Redlich–Kwong or any other equation of state, it would depend on the substance being studied and would be therefore of very limited utility.

Additionally, chemical potential is not mathematically well behaved. It approaches negative infinity as pressure approaches zero and this creates problems in doing real calculations.

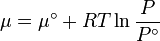

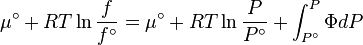

It is desirable that the expression for a real gas’ chemical potential to be similar to the one for an ideal gas. Therefore one can define a quantity, called fugacity, so that the chemical potential for a real gas becomes

with a given reference state to be discussed later. This is the usual form of the definition, but it may be solved for f to obtain the equivalent explicit form

Evaluation of fugacity for a real gas

Fugacity is used to better approximate the chemical potential of real gases than estimations made using the ideal gas law. Yet fugacity allows the use of many of the relationships developed for an idealized system.

In the real world, gases approach ideal gas behavior at low pressures and high temperatures; under such conditions the value of fugacity approaches the value of pressure. Yet no substance is truly ideal. At moderate pressures real gases have attractive interactions and at high pressures intermolecular repulsions become important. Both interactions result in a deviation from "ideal" behavior for which interactions between gas atoms or molecules are ignored.

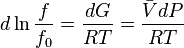

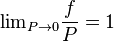

For a given temperature  , the fugacity

, the fugacity  satisfies the following differential relation:

satisfies the following differential relation:

where  is the Gibbs free energy,

is the Gibbs free energy,  is the gas constant,

is the gas constant,  is the fluid's molar volume, and

is the fluid's molar volume, and  is a reference fugacity which is generally taken as 1 bar. For an ideal gas, when

is a reference fugacity which is generally taken as 1 bar. For an ideal gas, when  , this equation reduces to the ideal gas law.

, this equation reduces to the ideal gas law.

Thus, for any two physical states at the same temperature, represented by subscripts 1 and 2, the ratio of the two fugacities is as follows:

For an ideal gas, this becomes simply  or

or

But for  , every gas is an ideal gas. Therefore, fugacity must obey the limit equation

, every gas is an ideal gas. Therefore, fugacity must obey the limit equation

We determine  by defining a new function

by defining a new function  , which is the difference between the actual molar volume and the ideal-gas molar volume:

, which is the difference between the actual molar volume and the ideal-gas molar volume:

We can obtain values for  experimentally easily by measuring

experimentally easily by measuring  ,

,  and

and  .

.

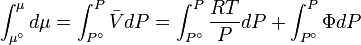

From the expression above we have

(It is more obvious here that  is the "extra" molar volume of a non-ideal gas.) We can then write

is the "extra" molar volume of a non-ideal gas.) We can then write

Where

Since the expression for an ideal gas was chosen to be  ,we must have

,we must have

Suppose we choose  . Since

. Since  , we obtain

, we obtain

The fugacity coefficient is defined as  = f/P (note that for an ideal gas,

= f/P (note that for an ideal gas,  = 1.0), and

it will then verify

= 1.0), and

it will then verify

The integral can be evaluated via graphical integration if we experimentally measure values for  while varying

while varying  .

.

We can then find the fugacity coefficient of a gas at a given pressure  and calculate

and calculate

.

The reference state for the expression of a real gas’ chemical potential is taken to be "ideal gas, at  = 1 bar and temperature

= 1 bar and temperature  ". Since in the reference state the gas is considered to be ideal (it is an hypothetical reference state), we can write that for the real gas

". Since in the reference state the gas is considered to be ideal (it is an hypothetical reference state), we can write that for the real gas

For a gas obeying the van der Waals equation, the explicit formula [4] for the fugacity is

This formula is difficult to use, since the pressure depends on the molar volume ![\bar{V}[p]](../I/m/3f126cb059fad8e3f4be3e744af34eeb.png) , so one must choose a volume, calculate the pressure, and then use these two values on the right-hand side of the equation.

, so one must choose a volume, calculate the pressure, and then use these two values on the right-hand side of the equation.

Fugacity of a pure liquid

For a pure fluid in vapor–liquid equilibrium, the vapor phase fugacity is equal to the liquid phase fugacity. At pressures above the saturation pressure, the liquid phase fugacity is:[5]

where  is the molar volume of the liquid.

is the molar volume of the liquid.

The fugacity correction factor for the vapor,  , should be evaluated at the saturation pressure and is unity when

, should be evaluated at the saturation pressure and is unity when  is low. The exponential term represents the Poynting correction factor and is usually near 1.0 unless pressures are very high. Frequently, the fugacity of the pure liquid is used as a reference state when defining and using mixture activity coefficients.

is low. The exponential term represents the Poynting correction factor and is usually near 1.0 unless pressures are very high. Frequently, the fugacity of the pure liquid is used as a reference state when defining and using mixture activity coefficients.

See also

- Activity (chemistry), the measure of the "effective concentration" of a species in a mixture

- Chemical equilibrium

- Electrochemical potential

- Excess chemical potential

- Partial molar property

- Thermodynamic equilibrium

- Fugacity capacity

- Multimedia fugacity model

References

- ↑ Peter Atkins and Julio de Paula, Atkins' Physical Chemistry (8th edn, W.H. Freeman 2006), p.112

- ↑ Atkins, Peter; John W. Locke (January 2002). Atkins' Physical Chemistry (7th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-879285-9.

- ↑ Lewis, Gilbert Newton (June 1901). "The Law of Physico-Chemical Change". Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 37 (4): 49–69. doi:10.2307/20021635.

- ↑ David, Carl W., "Fugacity Examples 2: The fugacity of a “hard-sphere” semi-ideal gas and the van der Waals gas" (2015). Chemistry Education Materials. Paper 91. http://digitalcommons.uconn.edu/chem_educ/91

- ↑ Prausnitz et al. Molecular Thermodynamics of Fluid Phase Equilibria 3ed. Prentice-Hall: 1999, pp.40-43.

External links

Video lectures

- Thermodynamics, University of Colorado-Boulder, 2011

![RT \ln \frac{f}{p}

=\frac{RTb}{\bar{V}[p]-b} - \frac{2a}{\bar{V}[p]}

- RT \ln

\left ( 1 - \frac{a(\bar{V}[p]-b)}{RT\bar{V}[p]^2}

\right )](../I/m/d28a564fa1ef9b097c33e2dd674ead3a.png)

![f^{\rm liq}(T, P)=\phi^{\rm sat}P^{\rm sat}{\rm exp}\left[\int_{P^{\rm sat}}^P{v_{\rm liq} \over RT}dP\right]](../I/m/e6ae566e9a8bd186d444dfc778f59a42.png)