Führer

Führer (German pronunciation: [ˈfyːʁɐ], spelled Fuehrer when the umlaut is not available) is a German title meaning leader or guide now most associated with Adolf Hitler. The word Führer in the sense of guide remains common in German, but because of its strong association with Nazi Germany, it comes with some stigma and negative connotations when used with the meaning of leader. The word Leiter is therefore used instead.

History

| Führer and Reich Chancellor of the German People Führer und Reichskanzler des deutschen Volkes | |

|---|---|

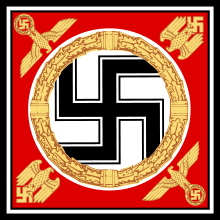

|

Hitler's Standard | |

| |

| Style | His Excellency , Mein Führer |

| Residence | Reich Chancellery |

| Appointer | Reichstag, Enabling Act of 1933 |

| Precursor |

Paul von Hindenburg (as president)[1][2] Himself (as chancellor) |

| Formation | 2 August 1934 |

| First holder | Adolf Hitler |

| Final holder | Adolf Hitler |

| Abolished | 23 May 1945 |

| Succession |

Karl Dönitz (as president) Joseph Goebbels (as chancellor) |

| Salary | 48,000 RM |

Origin of the title and its use as party leader

Führer was the unique name granted by Hitler to himself, in his function as Vorsitzender (chairman) of the Nazi Party. It was at the time common to refer to party leaders as "Führer", with an addition to indicate the leader of which party was meant. Hitler's adoption of the title was partly inspired by its earlier use by the Austrian Georg von Schönerer, a major exponent of pan-Germanism and German nationalism in Austria, whose followers also commonly referred to him as the Führer without qualification, and who also used the Sieg Heil-salute.[3] Hitler's choice for this political epithet was unprecedented in Germany. Like much of the early symbolism of Nazi Germany, it was modeled after Benito Mussolini's Italian Fascism. Mussolini's chosen epithet il Duce or "Dux" in Latin ('the Leader') was widely used, though, unlike Hitler, he never made it his official title. The Italian word Duce (unlike the German word Führer) is no longer used as a generic term for a leader, but almost always refers to Mussolini himself.

Hitler saw himself as the sole source of power in Germany, similar to the Roman emperors and German medieval leaders.[4] After the death of Paul Hindenburg in 1934, the Badonviller Marsch as well as the Personal standard of Adolf Hitler were used to evocate the presence of Hitler as leader and personification of the German state.[5]

As a political office

After Hitler's appointment as Reichskanzler (Chancellor of the Reich) the Reichstag passed the Enabling Act which allowed Hitler's cabinet to promulgate laws by decree.

One day before the death of Reichspräsident Paul von Hindenburg, Hitler and his cabinet decreed a law that merged the office of the president with that of Chancellor.[6] Hitler therefore assumed the President's powers without assuming the office itself – ostensibly out of respect for Hindenburg's achievements as a heroic figure in World War I. Though this law was in breach of the Enabling Act, which specifically precluded any laws concerning the Presidential office, it was approved by a referendum on 19 August.[1][2][7]

Hitler used the title Führer und Reichskanzler ("Leader and Chancellor"), highlighting the positions he already held in party and government, though in popular reception, the element Führer was increasingly understood not just in reference to the Nazi party but also in reference to the German people and the German state. Soldiers had to swear allegiance to Hitler as "Führer des deutschen Reiches und Volkes" (Leader of the German Reich and People) The title was changed on July 28, 1942 to "Führer des Großdeutschen Reiches" ("Leader of the Greater German Empire"). In his political testament, Hitler also refers to himself as Führer der Nation.[8]

Nazi Germany cultivated the Führerprinzip (leader principle),[9] and Hitler was generally known as just der Führer ("the Leader").

Ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Führer

One of the Nazis' most-repeated political slogans was Ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Führer – "One People, One Empire, One Leader". Bendersky says the slogan "left an indelible mark on the minds of most Germans who lived through the Nazi years. It appeared on countless posters and in publications; it was heard constantly in radio broadcasts and speeches." The slogan emphasized the absolute control of the party over practically every sector of German society and culture – with the churches the most notable exception. Hitler's word was absolute, but he had a narrow range of interest – mostly involving diplomacy and the military – and so his subordinates interpreted his will to fit their own interests.[10]

Military usage

According to the Constitution of Weimar, the President was Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces. Unlike “President”, Hitler did take this title (Oberbefehlshaber) for himself. When conscription was reintroduced in 1935, Hitler created the title of Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, a post held by the Minister for War. He retained the title of Supreme Commander for himself. Field Marshal Werner von Blomberg, then the Minister of War and one of those who created the Hitler oath, or the personal oath of loyalty of the military to Hitler became the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces while Hitler remained Supreme Commander. Following the Blomberg–Fritsch Affair in 1938, Hitler assumed the commander-in-chief's post as well and took personal command of the armed forces. However, he continued using the older formally higher title of Supreme Commander, which was thus filled with a somewhat new meaning. Combining it with "Führer", he used the style Führer und Oberster Befehlshaber der Wehrmacht ("Leader and Supreme Commander of the Wehrmacht"), yet a simple "Führer" since May 1942.

"Germanic" Führer

An additional title was adopted by Hitler on 23 June 1941, declaring himself the "Germanic Führer" (germanischer Führer) in addition to his duties as Führer of the German state and people.[11] This was done to emphasize Hitler's professed leadership of what the Nazis described as the "Nordic-Germanic master race", which peoples such as the Norwegians, Danes, Swedes, and Dutch, etc. were considered members of in addition to the Germans, and the intent to submerge these countries into Nazi Germany. Waffen-SS formations from these countries had to declare obedience to Hitler by addressing him in this fashion.[12] On 12 December 1941 the Dutch fascist Anton Mussert also addressed him as such when he proclaimed his allegiance to Hitler during a visit to the Reich Chancellery in Berlin.[13] He had wanted to address Hitler as Führer aller Germanen ("Führer of all Germanics"), but Hitler personally decreed the former style.[13] Historian Loe de Jong speculates on the difference between the two: Führer aller Germanen implied a position separate from Hitler's role as Führer und Reichskanzler des Grossdeutschen Reiches ("Führer and Reich Chancellor of the Greater German Empire"), while germanischer Führer served more as an attribute of that main function.[13] As late as 1944, however, occasional propaganda publications continued to refer to him by this unofficial title as well.[14]

Hitler's honorary titles

Nazi propaganda occasionally used a number of honorary titles when referencing Hitler.

- Supreme Judge of the German People (German: Oberster Richter des Deutschen Volkes) – Announced by Hitler on 30 June 1934 after the "Night of the Long Knives"[15]

- First Soldier of the German Reich (German: Erster Soldat des Deutschen Reiches) – This title was assumed by Hitler at the start of World War II on 1 September 1939. Addressing the Reichstag in the Kroll Opera House, Hitler appeared in a grey military uniform, declaring that he wanted "to be nothing but the first soldier of the German Reich", and pledging not to take it off until after victory had been achieved.[16]

- First Worker of the New Germany (German: Erster Arbeiter des neuen Deutschland).[17]

- Greatest Military Commander of All Time (German: Größter Feldherr aller Zeiten) – A title bestowed on Hitler by General Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel after the successful western campaign against France and the Low Countries in the summer of 1940.[18] Shortened derisively to "Gröfaz."

- Military Leader of Europe (German: Heerführer Europas) – Bestowed on Hitler after the start of Operation Barbarossa by the Nazi propaganda ministry in order to portray Hitler as the leader of a continental European struggle against Soviet Bolshevism.[19]

- High Protector of the Holy Mountain (German: Hoher Protektor des heiligen Berges) – After the Axis occupation of Greece in 1941, the monks of the Monastic State of Mount Athos asked Hitler to place the state under his personal protection, seeing him as a natural ally against the Bolsheviks and Jews. Hitler agreed, and the monks henceforth referred to him by this title until the authority of the Greek government was re-established near the end of the war.[20]

Military usage outside of Hitler

Führer has been used as a military title (compare Latin Dux) in Germany since at least the 18th century. The usage of the term "Führer" in the context of a company-sized military subunit in the German Army referred to a commander lacking the qualifications for permanent command. For example, the commanding officer of a company was (and is) titled "Kompaniechef" (literally, Company Chief), but if he did not have the requisite rank or experience, or was only temporarily assigned to command, he was officially titled "Kompanieführer". Thus operational commands of various military echelons were typically referred to by their formation title followed by the title Führer, in connection with mission-type tactics used by the German military forces. The term Führer was also used at lower levels, regardless of experience or rank; for example, a Gruppenführer was the leader of a squad of infantry (9 or 10 men).

Under the Nazis, the title Führer was also used in paramilitary titles (see Freikorps). Almost every Nazi paramilitary organization, in particular the SS and SA, had Nazi party paramilitary ranks incorporating the title of Führer. The SS including the Waffen-SS, like all paramilitary Nazi organisations, called all their members of any degree except the lowest Führer of something; thus confusingly, "Gruppenführer" was also an official rank title for a specific grade of general. The word Truppenführer was also a generic word referring to any commander or leader of troops, and could be applied to NCOs or officers at many different levels of command.

Modern German usage

In Germany, the isolated word Führer is usually avoided in political contexts, due to its intimate connection with Nazi institutions and with Hitler personally.

However, the term -führer is used in many compound words. Examples include Bergführer (mountain guide), Fremdenführer (tourist guide), Geschäftsführer (CEO or EO), Führerschein (driver's license), Führerstand or Führerhaus (driver's cab), Lok(omotiv)führer (train driver), Reiseführer (travel guide book), and Spielführer (team captain—also referred to as Mannschaftskapitän).

The use of alternate terms like "Chef" (a borrowing from the French, as is the English "chief", e.g. Chef des Bundeskanzleramtes) or Leiter, (often in compound words like Amtsleiter, Projektleiter or Referatsleiter) is usually not the result of replacing of the word "Führer", but rather using terminology that existed before the Nazis. The use of Führer to refer to a political party leader is rare today and Vorsitzender (chairman) is the more common term. However, the word Oppositionsführer ("leader of the (parliamentary) opposition") is more commonly used.

See also

Nazi German terminology derived from Führer

- Reichsführer-SS

- Reichsjugendführer

- Deputy Führer

- Oberster SA-Führer

- Führer Headquarters

- Führerbunker

- Führer Directives

- Führermuseum

- Führerprinzip

- Führerreserve

- Führerstadt

Other

References

- 1 2 Thamer, Hans-Ulrich (2003). "Beginn der nationalsozialistischen Herrschaft (Teil 2)". Nationalsozialismus I (in German). Bonn: Federal Agency for Civic Education. Archived from the original on February 8, 2008. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- 1 2 Winkler, Heinrich August. "The German Catastrophe 1933-1945". Germany: The Long Road West vol. 2: 1933-1990. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-0-19-926598-5. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ↑ Mitchell, Arthur H. (2007). Hitler's Mountain: The Führer, Obersalzberg, and the American Occupation of Berchtesgaden. Macfarland & Company Inc., Publishers, p. 15.

- ↑ Die Aussenpolitik des Dritten Reiches 1933-1939, Rainer F. Schmidt, Klett-Cotta, 2002

- ↑ Hitlers Tischgespräche im Führerhauptquartier Henry Picker, 05.03.2014

- ↑ Gesetz über das Staatsoberhaupt des Deutschen Reichs, 1 August 1934:

"§ 1 The office of the Reichspräsident is merged with that of the Reichskanzler. Therefore the previous rights of the Reichspräsident pass over to the Führer and Reichskanzler Adolf Hitler. He names his deputy." - ↑ Führer - Source

- ↑ Adolf Hitler - Politisches Testament 1945

- ↑ Nazi Conspiracy & Aggression Volume I Chapter VII

- ↑ Joseph W. Bendersky (2007). A Concise History of Nazi Germany: 1919-1945. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 105–6.

- ↑ De Jong, Louis (1974) (in Dutch). Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de tweede wereldoorlog: Maart '41 - Juli '42, p. 181. M. Nijhoff.

- ↑ Bramstedt, E. K. (2003). Dictatorship and Political Police: the Technique of Control by Fear, pp. 92-93. Routledge.

- 1 2 3 De Jong 1974, pp. 199-200.

- ↑ Adolf Hitler: Führer aller Germanen. Storm, 1944.

- ↑ Münchener Studien zur Politik, Nr. 9 1969

- ↑ Toland, John (1977). Adolf Hitler, pp. 569-570. Book Club Associates, Doubleday & Company, Inc.

- ↑ Kerschbaumer 1988, Faszination Drittes Reich: Kunst und Alltag der Kulturmetropole Salzburg, p. 53, ISBN 3-7013-0732-6

- ↑ Neumann, Bernhard Josef (2010) Däh, jetz ham mer den Kriech (da, jetzt haben wer den Krieg - 1939-1945), p. 401. Books on Demand GmbH, Norderstedt.

- ↑ Erdmann, Karl Dietrich (1978). Handbuch der deutschen Geschichte: Deutschland unter der Herrschaft des Nationalsozialismus, p. 541. Klett.

- ↑ The Hitler Icon: How Mount Athos Honored the Führer. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

External links

![]() The dictionary definition of Führer at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of Führer at Wiktionary

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||