Second-harmonic generation

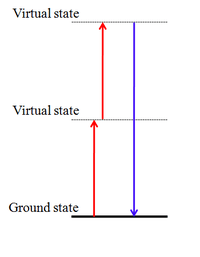

Second harmonic generation (also called frequency doubling or abbreviated SHG) is a nonlinear optical process, in which photons with the same frequency interacting with a nonlinear material are effectively "combined" to generate new photons with twice the energy, and therefore twice the frequency and half the wavelength of the initial photons. Second harmonic generation, as an even-order nonlinear optical effect, is only allowed in mediums without inversion symmetry. It is a special case of sum frequency generation.

Second harmonic generation was first demonstrated by Peter Franken, A. E. Hill, C. W. Peters, and G. Weinreich at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, in 1961.[1] The demonstration was made possible by the invention of the laser, which created the required high intensity coherent light. They focused a ruby laser with a wavelength of 694 nm into a quartz sample. They sent the output light through a spectrometer, recording the spectrum on photographic paper, which indicated the production of light at 347 nm. Famously, when published in the journal Physical Review Letters,[1] the copy editor mistook the dim spot (at 347 nm) on the photographic paper as a speck of dirt and removed it from the publication.[2] The formulation of SHG was initially described by N. Bloembergen and P. S. Pershan at Harvard in 1962.[3] In their extensive evaluation of Maxwell's equations at the planar interface between a linear and nonlinear medium, several rules for the interaction of light in non-linear mediums were elucidated.

Generating the second harmonic, often called frequency doubling, is also a process in radio communication; it was developed early in the 20th century, and has been used with frequencies in the megahertz range. It is a special case of frequency multiplication.

Types of SHG in crystals

Second harmonic generation occurs in three types, denoted 0, I and II. In Type 0 SHG two photons having extraordinary polarization with respect to the crystal will combine to form a single photon with double the frequency/energy and extraordinary polarization. In Type I SHG two photons having ordinary polarization with respect to the crystal will combine to form one photon with double the frequency and extraordinary polarization. In Type II SHG, two photons having orthogonal polarizations will combine to form one photon with double the frequency and extraordinary polarization. For a given crystal orientation, only one of these types of SHG occurs. In general to utilise Type 0 interactions a quasi-phase-matching crystal type will be required, for example periodically poled lithium niobate (PPLN).

Optical second harmonic generation

Since media with inversion symmetry are forbidden from generating second harmonic light, surfaces and interfaces make interesting subjects for study with SHG. In fact, second harmonic generation and sum frequency generation discriminate against signals from the bulk, implicitly labeling them as surface specific techniques. In 1982, T. F. Heinz and Y. R. Shen explicitly demonstrated for the first time that SHG could be used as a spectroscopic technique to probe molecular monolayers adsorbed to surfaces.[4] Heinz and Shen adsorbed monolayers of laser dye rhodamine to a planar fused silica surface; the coated surface was then pumped by a nanosecond ultra-fast laser. SH light with characteristic spectra of the adsorbed molecule and its electronic transitions were measured as reflection from the surface and demonstrated a quadratic power dependence on the pump laser power.

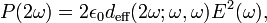

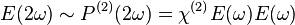

In SHG spectroscopy, one focuses on measuring twice the incident frequency 2ω given an incoming electric field  in order to reveal information about a surface. Simply (for a more in-depth derivation see below), the induced second-harmonic dipole per unit volume,

in order to reveal information about a surface. Simply (for a more in-depth derivation see below), the induced second-harmonic dipole per unit volume,  , can be written as

, can be written as

where  is known as the nonlinear susceptibility tensor and is a characteristic to the materials at the interface of study.[5] The generated

is known as the nonlinear susceptibility tensor and is a characteristic to the materials at the interface of study.[5] The generated  and corresponding

and corresponding  have been shown to reveal information about the orientation of molecules at a surface/interface, the interfacial analytical chemistry of surfaces, and chemical reactions at interfaces.

have been shown to reveal information about the orientation of molecules at a surface/interface, the interfacial analytical chemistry of surfaces, and chemical reactions at interfaces.

SHG from planar surfaces

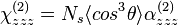

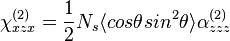

Early experiments in the field demonstrated second harmonic generation from metal surfaces.[6] Eventually, SHG was used to probe the air-water interface, allowing for detailed information about molecular orientation and ordering at one of the most ubiquitous of surfaces.[7] It can be shown that the specific elements of  :

:

where Ns is the adsorbate density, θ is the angle that the molecular axis z makes with the surface normal Z, and  is the dominating element of the nonlinear polarizability of a molecule at an interface, allow one to determine θ, given laboratory coordinates (x, y, z).[8] Using an interference SHG method to determine these elements of χ(2), the first molecular orientation measurement showed that the hydroxyl group of phenol pointed downwards into the water at the air-water interface (as expected due to the potential of hydroxyl groups to form hydrogen bonds). Additionally SHG at planar surfaces has revealed differences in pKa and rotational motions of molecules at interfaces.

is the dominating element of the nonlinear polarizability of a molecule at an interface, allow one to determine θ, given laboratory coordinates (x, y, z).[8] Using an interference SHG method to determine these elements of χ(2), the first molecular orientation measurement showed that the hydroxyl group of phenol pointed downwards into the water at the air-water interface (as expected due to the potential of hydroxyl groups to form hydrogen bonds). Additionally SHG at planar surfaces has revealed differences in pKa and rotational motions of molecules at interfaces.

SHG from non-planar surfaces

Second harmonic light can also be generated from surfaces that are ‘locally’ planar, but may have inversion symmetry (centrosymmetric) on a larger scale. Specifically, recent theory has demonstrated that SHG from small spherical particles (micro- and nanometer scale) is allowed by proper treatment of Rayleigh scattering.[9] At the surface of a small sphere, inversion symmetry is broken, allowing for SHG and other even order harmonics to occur.

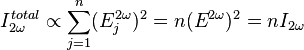

For a colloidal system of microparticles at relatively low concentrations, the total SH signal  , is given by:

, is given by:

where  is the SH electric field generated by the jth particle, and n the density of particles.[10] The SH light generated from each particle is coherent, but adds incoherently to the SH light generated by others (as long as density is low enough). Thus, SH light is only generated from the interfaces of the spheres and their environment and is independent of particle-particle interactions. It has also been shown that the second harmonic electric field

is the SH electric field generated by the jth particle, and n the density of particles.[10] The SH light generated from each particle is coherent, but adds incoherently to the SH light generated by others (as long as density is low enough). Thus, SH light is only generated from the interfaces of the spheres and their environment and is independent of particle-particle interactions. It has also been shown that the second harmonic electric field  scales with the radius of the particle cubed, a3.

scales with the radius of the particle cubed, a3.

Besides spheres, other small particles like rods have been studied similarly by SHG.[11] Both immobilized and colloidal systems of small particles can be investigated. Recent experiments using second harmonic generation of non-planar systems include transport kinetics across living cell membranes[12] and demonstrations of SHG in complex nanomaterials.[13]

Second harmonic generation microscopy

In biological and medical science, the effect of second harmonic generation is used for high-resolution optical microscopy. Because of the non-zero second harmonic coefficient, only non-centrosymmetric structures are capable of emitting SHG light. One such structure is collagen, which is found in most load-bearing tissues. Using a short-pulse laser such as a femtosecond laser and a set of appropriate filters the excitation light can be easily separated from the emitted, frequency-doubled SHG signal. This allows for very high axial and lateral resolution comparable to that of confocal microscopy without having to use pinholes. SHG microscopy has been used for extensive studies of the cornea[14] and lamina cribrosa sclerae,[15] both of which consist primarily of collagen.

Commercial uses

Second harmonic generation is used by the laser industry to make green 532 nm lasers from a 1064 nm source. The 1064 nm light is fed through a bulk KDP crystal. In high-quality diode lasers the crystal is coated on the output side with an infrared filter to prevent leakage of intense 1064 nm or 808 nm infrared light into the beam. Both of these wavelengths are invisible and do not trigger the defensive "blink-reflex" reaction in the eye and can therefore be a special hazard to the human eyes. Furthermore, some laser safety eyewear intended for argon or other green lasers may filter out the green component (giving a false sense of safety), but transmit the infrared. Nevertheless, some "green laser pointer" products have become available on the market which omit the expensive infrared filter, often without warning.[16] Second harmonic generation is also used for measuring ultra short pulse width by means of intensity auto-correlation.

Derivation of second harmonic generation

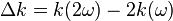

The simplest case for analysis of second harmonic generation is a plane wave of amplitude E(ω) traveling in a nonlinear medium in the direction of its k vector. A polarization is generated at the second harmonic frequency

The wave equation at 2ω (assuming negligible loss and asserting the slowly varying envelope approximation) is

where  .

.

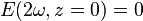

At low conversion efficiency (E(2ω) << E(ω)) the amplitude  remains essentially constant over the interaction length,

remains essentially constant over the interaction length,  . Then, with the boundary condition

. Then, with the boundary condition  we obtain

we obtain

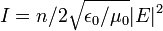

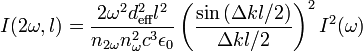

In terms of the optical intensity,  , this is,

, this is,

This intensity is maximized for the phase matched condition Δk = 0. If the process is not phase matched, the driving polarization at 2ω goes in and out of phase with generated wave E(2ω) and conversion oscillates as sin(Δkl/2). The coherence length is defined as  . It does not pay to use a nonlinear crystal much longer than the coherence length. (Periodic poling and quasi-phase-matching provide another approach to this problem.)

. It does not pay to use a nonlinear crystal much longer than the coherence length. (Periodic poling and quasi-phase-matching provide another approach to this problem.)

Second harmonic generation with depletion

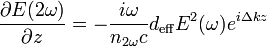

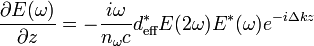

When the conversion to 2nd harmonic becomes significant it becomes necessary to include depletion of the fundamental. One then has the coupled equations:

,

,

,

,

where  denotes the complex conjugate. For simplicity, assume phase matched generation (

denotes the complex conjugate. For simplicity, assume phase matched generation ( ). Then, energy conservation requires that

). Then, energy conservation requires that

![n_{2\omega}[E^*(2\omega)\frac{\partial E(2\omega)}{\partial z}+c.c.]=-n_\omega[E(\omega)\frac{\partial E^*(\omega)}{\partial z} + c.c.]](../I/m/a2ea209f4f24fcb0a41653d87abc7b79.png)

where  is the complex conjugate of the other term, or

is the complex conjugate of the other term, or

.

.

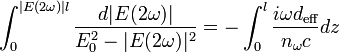

Now we solve the equations with the premise

and obtain

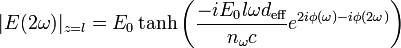

![\frac{d|E(2\omega)|}{dz} = - \frac{i\omega d_{\text{eff}}}{n_\omega c}\left[E_0^2-|E(2\omega)|^2\right]e^{2i\phi(\omega) - i\phi(2\omega)}](../I/m/305d0101e09d176f85fdeec54e7e0814.png)

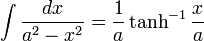

Using

we get

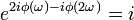

If we assume a real  , the relative phases for real harmonic growth must be such that

, the relative phases for real harmonic growth must be such that  . Then

. Then

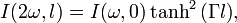

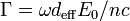

or

where  . From

. From  , it also follows that

, it also follows that

References

- 1 2 Franken, P.; Hill, A.; Peters, C.; Weinreich, G. (1961). "Generation of Optical Harmonics". Physical Review Letters 7 (4): 118–119. Bibcode:1961PhRvL...7..118F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.7.118.

- ↑ Haroche, Serge (October 17, 2008). "Essay: Fifty Years of Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics in Physical Review Letters". Physical Review Letters 101 (16). Bibcode:2008PhRvL.101p0001H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.160001.

- ↑ Bloembergen, N.; Pershan, P. S. (1962). "Light Waves at Boundary of Nonlinear Media". Physical Review 128 (2): 606–622. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.128.606.

- ↑ Heinz, T. F.; et al. (1982). "Spectroscopy of Molecular Monolayers by Resonant 2nd-Harmonic Generation". Physical Review Letters 48 (7): 478–81. Bibcode:1982PhRvL..48..478H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.48.478.

- ↑ Shen, Y. R. (1989). "Surface-Properties Probed by 2nd-Harmonic and Sum-Frequency Generation". Nature 337 (6207): 519–25. doi:10.1038/337519a0.

- ↑ Brown, F.; Matsuoka, M. (1969). "Effect of Adsorbed Surface Layers on Second-Harmonic Light from Silver". Physical Review 185 (3): 985–987. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.185.985.

- ↑ Eisenthal, K. B. (1992). "Equilibrium and Dynamic Processes at Interfaces by 2nd Harmonic and Sum Frequency Generation". Annual Review of Physical Chemistry 43 (1): 627–61. doi:10.1146/annurev.physchem.43.1.627.

- ↑ Kemnitz, K.; et al. (1986). "The Phase of 2nd-Harmonic Light Generated at an Interface and Its Relation to Absolute Molecular-Orientation". Chemical Physics Letters 131 (4-5): 285–90. doi:10.1016/0009-2614(86)87152-4.

- ↑ Dadap, J. I.; Shan, J.; Heinz, T. F. (2004). "Theory of Optical Second-Harmonic Generation from a Sphere of Centrosymmetric Material: Small-Particle Limit". Journal of the Optical Society of America B-Optical Physics 21 (7): 1328–47. doi:10.1364/JOSAB.21.001328.

- ↑ Eisenthal, K. B. (2006). "Second Harmonic Spectroscopy of Aqueous Nano- and Microparticle Interfaces". Chemical Reviews 106 (4): 1462–77. doi:10.1021/cr0403685.

- ↑ Chan, S. W.; et al. (2006). "Second Harmonic Generation in Zinc Oxide Nanorods". Applied Physics B-Lasers and Optics 84 (1-2): 351–55. doi:10.1007/s00340-006-2292-0.

- ↑ Zeng, Jia; et al. (2013). "Time-Resolved Molecular Transport across Living Cell Membranes". Biophysical Journal 104 (1): 139–45. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2012.11.3814.

- ↑ Fan, W.; et al. (2006). "Second Harmonic Generation from a Nanopatterned Isotropic Nonlinear Material". Nano Letters 6 (5): 1027–30. doi:10.1021/nl0604457.

- ↑ Han, M; Giese, G; Bille, J (2005). "Second harmonic generation imaging of collagen fibrils in cornea and sclera". Optics Express 13 (15): 5791–7. Bibcode:2005OExpr..13.5791H. doi:10.1364/OPEX.13.005791. PMID 19498583.

- ↑ Brown, Donald J.; Morishige, Naoyuki; Neekhra, Aneesh; Minckler, Don S.; Jester, James V. (2007). "Application of second harmonic imaging microscopy to assess structural changes in optic nerve head structure ex vivo". Journal of Biomedical Optics 12 (2): 024029. Bibcode:2007JBO....12b4029B. doi:10.1117/1.2717540. PMID 17477744.

- ↑ A warning about IR in green cheap green laser pointers

External links

Articles on second harmonic generation

- Parameswaran, K. R., Kurz, J. R., Roussev, M. M. & Fejer, "Observation of 99% pump depletion in single-pass second-harmonic generation in a periodically poled lithium niobate waveguide", Optics Letters, 27, p. 43-45 (January 2002).

- "Frequency doubling". Encyclopedia of laser physics and technology. Retrieved 2006-11-04.