Freer Gallery of Art

| |

Location in Washington, D.C. | |

| Established | 1923 |

|---|---|

| Location | 1050 Independence Avenue, Washington, D.C. |

| Coordinates | 38°53′17″N 77°01′39″W / 38.888135°N 77.02739°W |

| Director | Julian Raby |

| Public transit access |

|

| Website | |

|

Freer Gallery Of Art | |

| |

|

Front entrance to the Freer Gallery of Art | |

| Built | 1923 |

| Architect | Platt, Charles A. |

| Architectural style | Late 19th And 20th Century Revivals, Florentine Renaissance |

| NRHP Reference # | [1] |

| Added to NRHP | June 23, 1969 |

The Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery form the Smithsonian Institution's national museums of Asian art in the United States. The Freer and Sackler galleries house the largest Asian art research library in the country and contains art from East Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, the Islamic world, the ancient Near East, and ancient Egypt, as well as a significant collection of American art. The gallery is located on the south side of the National Mall in Washington, D.C., adjacent to the physically connected Sackler Gallery. The museum is open 364 days a year (being closed on Christmas), and is administered by a single staff with the Sackler Gallery. The galleries are among the most visited art museums in the world.

The Freer houses over 26,000 objects spanning 6,000 years of history from the Neolithic to modern eras. The collections include ancient Egyptian stone sculpture and wooden objects, ancient Near Eastern ceramics and metalware, Chinese paintings and ceramics, Korean pottery and porcelain, Japanese folding screens, Persian manuscripts, and Buddhist sculpture. In addition to Asian art, the Freer also contains the famous Peacock Room by American artist James McNeill Whistler which serves as the centerpiece to the Freer's American art collection.

The museum offers free tours to the public and presents a full schedule events for the public including films, lectures, symposia, concerts, performances, and discussions. Over 11,000 objects from the Freer|Sackler collections are fully searchable and available online.[2] The Freer was also featured in the Google Art Project, which offers online viewers close-up views of selected items from the Freer.[3]

History

Founding

The gallery was founded by Detroit railroad-car manufacturer and self-taught connoisseur Charles Lang Freer. He owned the largest collection of works by American artist James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903) and became a patron and friend of the famously irascible artist. Whistler made it very clear to Freer that if he helped him to build the premier Whistler collection, then that collection would have to be displayed in a city where tourists went.[4]

In 1908, Charles Moore, a former aide to Michigan United States Senator, James McMillin and the chairman of the United States Commission of Fine Arts, moved from Washington, D.C., to Detroit. Moore became friends with Freer, who was director of the Michigan Car Company, and persuaded Freer to permanently exhibit his 8,000-piece collection of Oriental art in Washington, D.C. Before then, Freer informally proposed to President Theodore Roosevelt that he give to the nation his art collection, funds to construct a building, and an endowment fund to provide for the study and acquisition of "very fine examples of Oriental, Egyptian, and Near Eastern fine arts."[5]

Travelers impressed by the beauty of the National Mall in Washington, D.C., can thank three Detroiters for their role in creating it. The mall was the brainchild of James McMillan, a Michigan United States senator and former business competitor to Freer. Charles Freer for his enormous donation to the Smithsonian, and Moore for carrying out the Washington mall concept. The Freer gift was accepted on behalf of the government by the Smithsonian Board of Regents in 1906. Freer’s will, however, contained certain requirements that only objects from the permanent collection could be exhibited in the gallery, and that none of the art could be exhibited elsewhere. Freer felt strongly that all of the museum’s holding should be readily accessible to scholars at all times. In addition, Freer's bequest to the Smithsonian came with the proviso that he would execute full curatorial control over the collection until his death. The Smithsonian initially hesitated at the requirements but the intercession of President Theodore Roosevelt allowed for the project to proceed. The Freer Gallery possesses an autographed letter from Roosevelt inviting Freer to visit him at the White House, reflecting the personal interest Roosevelt showed in the development of the museum. Freer died before the art gallery was completed.

Construction and architecture

Construction of the gallery began in 1916 and was completed in 1921, after a delay due to World War I.[6] On May 9, 1923, the Freer Gallery of Art was opened to the public. Designed by American architect and landscape planner Charles A. Platt, the Freer is an Italian Renaissance-style building inspired by Freer's visits to palazzos in Italy.[7] It is reported that in a meeting with architect Charles Platt at the Plaza Hotel in New York City, Freer jotted down his ideas for a classical, well-proportioned building on a napkin.[8] The gallery is constructed primarily of granite: the exterior of the Freer is pink granite quarried in Milford, Massachusetts, the courtyard has a carnelian granite fountain and walls of unpolished Tennessee white marble. The gallery's interior walls are Indiana limestone, and the floors are polished Tennessee marble.

A major renovation of the building, which culminated in a grand reopening in 1993, greatly expanded storage and exhibition space by connecting the Freer and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. With the addition of the connecting gallery, the Freer has 39,039 square feet of public space. The original structure designed by Platt remains intact, including the Eugene and Agnes E. Meyer Auditorium which serves as the venue for many public programs.

Current

After opening in 1923, the Freer served as the Smithsonian's first museum dedicated to the fine arts.[9] The Freer was also the first Smithsonian museum created from a private collector's bequest. Through the years, the collections have grown through gifts and purchases to nearly triple the size of Freer's original donation: nearly 18,000 works of Asian art have been added since Freer's death in 1919.

The Freer is now connected by an underground exhibition space to the neighboring Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. Although their collections are stored and exhibited separately, the two museums share a director, administration, and staff.

Exhibitions

Because one of the main conditions of Charles Lang Freer donation was that only items from his collection may be exhibited at the gallery, the Freer does not borrow from or lend out items to other institutions. However, due to the 26,000 objects in the gallery's collections, they are still able to present exhibitions internationally recognized for both depth and quality.

The Freer's exhibits which continue indefinitely include:

- Freer & Whistler: Points of Contact

- Feast Your Eyes: A Taste for Luxury in Ancient Iran

- Arts of the Islamic World

- Ancient Chinese Jades and Bronzes

- Ancient Chinese Pottery and Bronze

- Chinese Ceramics: 10th–13th Century

- Silk Road Luxuries from China

- Japanese Screens

- The Religious Art of Japan

- Cranes and Clouds: The Korean Art of Ceramic Inlay

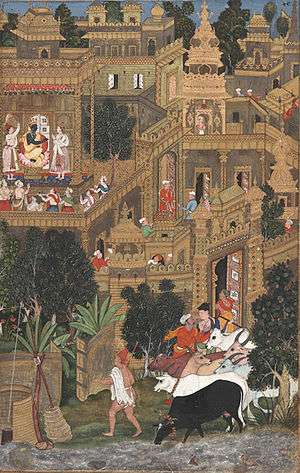

- Arts of the Indian Subcontinent and the Himalayas

The Freer also has a number rotating/temporary exhibits, which currently include:

- The Peacock Room Comes to America, a recreation of Whistler's famed room as it first appeared in Freer's home (ending Spring 2013)

- Enlightened Beings: Buddhism in Chinese Painting, (ending February 24, 2013)

- Whistler’s Neighborhood: Impressions of a Changing London, (ending September 8, 2013)

- Promise of Paradise: Early Chinese Buddhist Sculpture

A full list of all past, current, and future exhibitions can be found on the Freer|Sackler exhibitions page.

American art at the Freer

Freer began collecting American art in the 1880s.[8] In 1890, after meeting James Abbott McNeill Whistler, an American artist influenced by Japanese prints and Chinese ceramics, Freer began to expand his collections to include Asian art. He maintained his interest in American art, however, amassing a collection of over 1,300 works by Whistler, which is considered the world's finest.

One of the most well-known exhibits at the Freer is The Peacock Room, an opulent London dining room painted by Whistler in 1876–77. The room was designed for British shipping magnate F.R. Leyland[10] and is lavishly decorated with green and gold peacock motifs. Purchased by Freer in 1904 and installed in the Freer Gallery after his death, the Peacock Room is on permanent display.

The Freer also has works by Thomas Dewing (1851–1938), Dwight Tryon (1849–1925), Abbott Handerson Thayer (1849–1921), Childe Hassam (1859–1935), Winslow Homer (1836–1910), Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907), Willard Metcalf (1858–1925), John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), and John Twachtman (1853–1902).[11]

F|S Online

The Freer|Sackler provides several online resources for exploring the art and culture of Asia and its American art collections. Besides the collections objects viewable online, thousands of photographs, archeological diaries, maps, and archaeological squeezes (impressions of carvings) have been digitized and are used by researchers from around the world.

The Freer|Sackler's "Explore + Learn" pages go in-depth into some of the museum's most popular exhibitions, including Waves at Matsushima and Shahnama: 1000 Years of the Persian Book of Kings, with interactive high-resolution images, videos and galleries.

For educators and families, the museum provides project ideas and resources including printable handouts, teachers' guides, and lesson plans. F|S also produces podcasts of concerts, storytelling, and lectures, and videos on the F|S YouTube channel.

F|S Archives and Library

The Freer|Sackler Archives houses over 120 important manuscripts collections relevant to the study of America's encounter with Asian art and culture. The core collection is the personal papers of gallery founder Charles Lang Freer, which includes his purchase records, diaries, and personal correspondence with public figures such as artists, dealers and collectors. Freer's extensive correspondence with James McNeill Whistler forms one of the largest sources of primary documents about the American artist. Other significant collections in the Archives includes the papers (notebooks, letters, photography, squeezes) and personal objects of the German archaeologist Ernst Herzfeld (1879–1946), documenting his research at Samarra, Persepolis and Pasargadae. The papers of Carl Whiting Bishop [12] Dwight William Tryon, Myron Bement Smith,[13] Benjamin March[14] and Henri Vever [15] are also located at the Archives. The Archives also holds over 125,000 photographs of Asia dating from the 19th and early 20th centuries. Highlights of photographic holdings include the Henry and Nancy Rosin Collection of 19th century photography of Japan, the 1903-1904 photographs of the Chinese Empress Dowager Cixi, and photographs of Iran by Antoin Sevruguin.[16]

The Archives is open by appointment Mondays through Thursdays, from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. and appointments may be scheduled by calling (202) 633-0533.

The Freer|Sackler Library is the largest Asian art research library in the United States. Open to the public five days a week (except federal holidays) without appointment, the library collection consists of more than 86,000 volumes, including nearly 2,000 rare books. Half the volumes are written and catalogued in Asian languages. Originating from the collection of four thousand monographs, periodical issues, offprints, and sales catalogues that Charles Lang Freer donated to the Smithsonian Institution as part of his gift to the nation, the F|S Library maintains the highest standards for collecting materials an active program of purchases, gifts, and exchanges.

In July 1987 the library moved to its new home in the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. Today it supports activities of both museums, such as collection development, exhibition planning, publications, and other scholarly and educational projects. Its published and unpublished resources—in the fields of Asian art and archaeology, conservation, painting, sculpture, architecture, drawings, prints, manuscripts, books, and photography—are available to museum staff, outside researchers, and the visiting public.

Public programs

The Eugene and Agnes E. Meyer Auditorium, named after American financier and publisher Eugene Meyer is located in the Freer and provides a venue for a broad variety of free public programs. These programs include exceptional concerts of music and dance, lectures, chamber music, and dramatic presentations. It is also known for its well-curated film series, highlighting a wide variety of Asian cultures (including a Korean Film Festival and Iranian Film Festival).

The Freer and Sackler galleries also present family programs such as ImaginAsia and ExplorAsia workshops. The Freer and Sackler's also presents family festivals such as its annual Nowruz celebration in March. Hands-on workshops, including the popular Inner-Artist, Art ID, and educator workshops, allow adult visitors to tour and then create their own artistic responses.

Most recently, the museums began the series Asia After Dark, opening up the space for musicians, dancing, Asian cuisine, and other after-work adventures. The Freer and Sackler's 'We Stand With Japan' in 2011 hosted Steve Aoki.[17]

Free drop-in tours are available daily and guide visitors through both featured exhibitions and specific themes in both the Freer and Sackler galleries, and a wide range of public lectures provide in-depth experiences with prominent artists and scholars.

Conservation

Care of the collections began before the museum came into existence as Charles Lang Freer, the founder of the Freer Gallery of Art, hired Japanese painting restorers to care for his works and to prepare them for their eventual home as part of the Smithsonian Institution. In 1932, the Freer Gallery of Art hired a full-time Japanese restorer and established what was to become the East Asian Painting Conservation Studio. This facility remains one of the few in the United States that specializes in the conservation of Asian paintings.[6] The Technical Laboratory was established in 1951 when chemist Rutherford J. Gettens moved from the Fogg Museum at Harvard University to the Freer. The laboratory was the first Smithsonian facility devoted to the use of scientific methods for the study of works of art. Over the years, the work of the Technical Laboratory expanded to include objects, paper, and exhibits conservation. The Technical Laboratory and the East Asian Painting Conservation Studio merged in 1990 to create the Department of Conservation and Scientific Research for both the Freer and Sackler Galleries.[18]

The conservators in the Department of Conservation and Scientific Research care for and treat works of art in the collection and prepare them for exhibition. Conservation-restoration at the Freer and Sackler is broken into four sections: Asian Paintings(one of the only East Asian painting conservation studios in the U.S using traditional methods), Objects, Paper, and Exhibitions. The department works to ensure long-term preservation and storage, safe handling, exhibition, and transport of artworks in the permanent collection, as well as those on loan. In addition, conservators are responsible for conducting technical examinations of objects already in the collection and those under consideration for acquisition. They also collaborate frequently with the department’s scientists on technical and applied research. Training and professional outreach efforts are an integral part of the department’s commitment to educating future conservators, museum professionals, and the public about conservation.

Scholarship

The Freer has had a long tradition in serving as a center for inquiry and advanced scholarship about Asia. The Freer not only presents a lectures and symposia to the public, it also copublishes the Ars Orientalis with the University of Michigan Department of History of Art. Ars Orientalis is a peer-reviewed annual volume of scholarly articles and occasional reviews of books on the art and archaeology of Asia, the ancient Near East, and the Islamic world.[19]

The Freer and Sackler, along with the Metropolitan Center for Far Eastern Art Studies in Kyoto, Japan, presents the Shimada Prize for distinguished scholarship in the history of East Asian art. The award was established in 1992 in honor of Professor Shimada Shujiro, by the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and by The Metropolitan Center for Far Eastern Art Studies in Kyoto, Japan. Several fellowships are also available to support graduate students and visiting scholars, including the Andrew W. Mellon Fellowship, Anne Van Biema Fellowship (Japanese Visual Arts), Iran Heritage Foundation (IHF) Fellowship (Persian art), Lunder Fellowship, J. S. Lee Memorial Fellowship (Chinese Art), Smithsonian Institution Fellowship, and the Freer Fellowship.[20]

Freer and Sackler curators are also involved in dozens of ongoing research projects, often with colleagues from institutions around the world. The results of their work can be seen in a variety of published formats, including exhibition catalogues, scholarly publications, and online publications.[21]

Mission

| “ | As Smithsonian museums, the Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery hold in trust the nation’s extraordinary collections of Asian art and of American art of the late nineteenth-century aesthetic movement.

Our mission is to encourage enjoyment and understanding of the arts of Asia and the cultures that produced them. We use works of art to inspire study and provoke thought.[22] |

” |

Gallery

China

India

Egypt

Japan

Nepal

Persia

Korea

Syria

Kushan

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Freer Gallery of Art. |

- Ernst Herzfeld and Persepolis

- Biblical Manuscripts in the Freer Collection

- Chinese painting

- History of art

- History of painting

- Indian art

- Islamic art

- Japanese painting

- Lin Tinggui

- Pewabic Pottery

- Zhou Jichang

- Charles Lang Freer medal

- J. Keith Wilson

References

- ↑ Staff (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "Collections | Freer and Sackler Galleries". Asia.si.edu. 2013-03-15. Retrieved 2014-06-06.

- ↑ "Freer|Sackler: The Smithsonian's Museums of Asian Art - Google Cultural Institute". Googleartproject.com. Retrieved 2014-06-06.

- ↑ Linda Merrill, a former curator of American art at the Freer Gallery, editor of With Kindest Regards: The Correspondence of Charles Lang Freer and James McNeill Whistler, and co-author of Freer: A Legacy of Art.

- ↑ Smithsonian Institution Archives, http://siarchives.si.edu/history/freer-gallery-art

- 1 2 Smithsonian Institution Archives

- ↑ Caemmerer, H. Paul. "Charles Moore and the Plan of Washington." Records of the Columbia Historical Society. Vol. 46/47 (1944/1945): 237-258, 256.

- 1 2 "Charles Lang Freer | About Us | Freer and Sackler Galleries". Asia.si.edu. 2013-03-15. Retrieved 2014-06-06.

- ↑ "The Freer Gallery of Art | About Us | Freer and Sackler Galleries". Asia.si.edu. 2013-03-15. Retrieved 2014-06-06.

- ↑ "A Closer Look - James McNeill Whistler - Peacock Room". Asia.si.edu. Retrieved 2014-06-06.

- ↑ "Freer and Sackler Galleries | Collections". Asia.si.edu. 2013-03-15. Retrieved 2014-06-06.

- ↑ Carl Whiting Bishop Papers,

- ↑ Myron Bement Smith Papers

- ↑ Benjamin March Papers

- ↑ Henri Vever Papers

- ↑ "Archives: Highlights | Freer and Sackler Galleries". Asia.si.edu. 2013-03-15. Retrieved 2014-06-06.

- ↑ "Asia After Dark - Freer Gallery of Art - We Stand with Japan | Flickr - Photo Sharing!". Flickr. 2011-05-14. Retrieved 2014-06-06.

- ↑ Archived February 2, 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Ars Orientalis Freer and Sackler Galleries". Asia.si.edu. 2013-03-15. Retrieved 2014-06-06.

- ↑ "Fellowships & Internships | Research | Freer and Sackler Galleries". Asia.si.edu. 2013-03-15. Retrieved 2014-06-06.

- ↑ "Curatorial Research | Freer and Sackler Galleries". Asia.si.edu. 2013-03-15. Retrieved 2014-06-06.

- ↑ "Mission". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)