Polarization density

| Electromagnetism |

|---|

|

|

|

In classical electromagnetism, polarization density (or electric polarization, or simply polarization) is the vector field that expresses the density of permanent or induced electric dipole moments in a dielectric material. When a dielectric is placed in an external electric field, its molecules gain electric dipole moment and the dielectric is said to be polarized. The electric dipole moment induced per unit volume of the dielectric material is called the electric polarization of the dielectric.[1][2]

Polarization density also describes how a material responds to an applied electric field as well as the way the material changes the electric field, and can be used to calculate the forces that result from those interactions. It can be compared to magnetization, which is the measure of the corresponding response of a material to a magnetic field in magnetism. The SI unit of measure is coulombs per square meter, and polarization density is represented by a vector P.[2]

Definition

An external electric field that is applied to a dielectric material, causes a displacement of bound charged elements. These are elements which are bound to molecules and are not free to move around the material. Positive charged elements are displaced in the direction of the field, and negative charged elements are displaced opposite to the direction of the field. The molecules may remain neutral in charge, yet an electric dipole moment forms.[3][4]

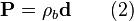

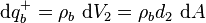

For a certain volume element in the material  , which carries a dipole moment

, which carries a dipole moment  , we define the polarization vector P:

, we define the polarization vector P:

In general, the dipole moment  changes from point to point within the dielectric. Hence, the polarization density P of an infinitesimal change dp in the dipole moment for a given change dV in the volume is:

changes from point to point within the dielectric. Hence, the polarization density P of an infinitesimal change dp in the dipole moment for a given change dV in the volume is:

The net charge appearing as a result of polarization is called bound charge and denoted  .

.

This definition of polarization as a "dipole moment per unit volume" is widely adopted, though in some cases it can bring to ambiguities and paradoxes.[5]

Other Expressions

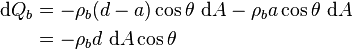

Let a volume dV be isolated inside the dielectric. Due to polarization the positive bound charge  will be displaced a distance

will be displaced a distance  relative to the negative bound charge

relative to the negative bound charge  , giving rise to a dipole moment

, giving rise to a dipole moment  . Replacing this expression into (1) we get:

. Replacing this expression into (1) we get:

Since the charge  bounded in the volume dV is equal to

bounded in the volume dV is equal to  the equation for P becomes:[3]

the equation for P becomes:[3]

where  is the density of the bound charge in the volume under consideration.

is the density of the bound charge in the volume under consideration.

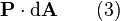

Gauss's Law for the Field of P

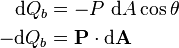

For a given volume V enclosed by a surface S, the bound charge  inside it is equal to the flux of P through S taken with the negative sign, or

inside it is equal to the flux of P through S taken with the negative sign, or

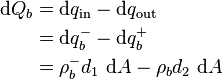

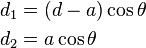

Proof: Let a surface area S envelope part of a dielectric. Upon polarization negative and positive bound charges will be displaced. Let d1 and d2 be the distances of the bound charges  and

and  , respectively, from the plane formed by the element of area dA after the polarization. And let dV1 and dV2 be the volumes enclosed below and above the area dA.

, respectively, from the plane formed by the element of area dA after the polarization. And let dV1 and dV2 be the volumes enclosed below and above the area dA.

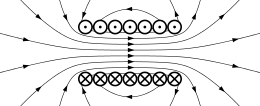

Above: an elementary volume dV = dV1+ dV2 (bounded by the element of area dA) so small, that the dipole enclosed by it can be thought as that produce by two elementary opposite charges. Below, a planar view (click in the image to enlarge).

Above: an elementary volume dV = dV1+ dV2 (bounded by the element of area dA) so small, that the dipole enclosed by it can be thought as that produce by two elementary opposite charges. Below, a planar view (click in the image to enlarge).It follows that the negative bound charge

moved from the outer part of the surface dA inwards, while the positive bound charge

moved from the outer part of the surface dA inwards, while the positive bound charge  moved from the inner part of the surface outwards.

moved from the inner part of the surface outwards.By the law of conservation of charge the total bound charge

left inside the volume

left inside the volume  after polarization is:

after polarization is:Since

and (see image to the right)

The above equation becomes

By (2) it follows that

, so we get:

, so we get:And by integrating this equation over the entire closed surface S we find that

which completes the proof.

Differential Form

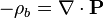

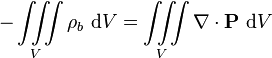

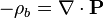

By the divergence theorem, Gauss's law for the field P can be stated in differential form as:

,

,

where ∇ · P is the divergence of the field P through a given surface containing the bound charge density  .

.

Proof: By the divergence theorem we have that  ,

,

for the volume V containing the bound charge

. And since

. And since  is the integral of the bound charge density

is the integral of the bound charge density  taken over the entire volume V enclosed by S, the above equation yields

taken over the entire volume V enclosed by S, the above equation yields ,

,

which is true if and only if

Relationship between the fields of P and E

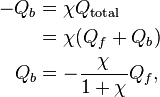

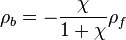

Homogeneous, Isotropic Dielectrics

In a homogeneous, linear and isotropic dielectric medium, the polarization is aligned with and proportional to the electric field E:[7]

where ε0 is the electric constant, and χ is the electric susceptibility of the medium. Note that χ is just a scalar. This is a particular case due to the isotropy of the dielectric.

Taking into account this relation between P and E, equation (3) becomes:[3]

The expression in the integral is Gauss's law for the field E which yields the total charge, both free  and bound

and bound  , in the volume V enclosed by S.[3] Therefore

, in the volume V enclosed by S.[3] Therefore

which can be written in terms of free charge and bound charge densities (by considering the relationship between the charges, their volume charge densities and the given volume):

Since within a homogeneous dielectric there can be no free charges  , by the last equation it follows that there is no bulk bound charge in the material

, by the last equation it follows that there is no bulk bound charge in the material  . And since free charges can get as close to the dielectric as to its topmost surface, it follows that polarization only gives rise to surface bound charge density (denoted

. And since free charges can get as close to the dielectric as to its topmost surface, it follows that polarization only gives rise to surface bound charge density (denoted  to avoid ambiguity with the volume bound charge density

to avoid ambiguity with the volume bound charge density  ).[3]

).[3]

may be related to P by the following equation:[8]

may be related to P by the following equation:[8]

where  is the normal vector to the surface S pointing outwards.

is the normal vector to the surface S pointing outwards.

Anisotropic Dielectrics

The class of dielectrics where the polarization density and the electric field are not in the same direction are known as anisotropic materials.

In such materials, the ith component of the polarization is related to the jth component of the electric field according to:[7]

This relation shows, for example, that a material can polarize in the x direction by applying a field in the z direction, and so on. The case of an anisotropic dielectric medium is described by the field of crystal optics.

As in most electromagnetism, this relation deals with macroscopic averages of the fields and dipole density, so that one has a continuum approximation of the dielectric materials that neglects atomic-scale behaviors. The polarizability of individual particles in the medium can be related to the average susceptibility and polarization density by the Clausius-Mossotti relation.

In general, the susceptibility is a function of the frequency ω of the applied field. When the field is an arbitrary function of time t, the polarization is a convolution of the Fourier transform of χ(ω) with the E(t). This reflects the fact that the dipoles in the material cannot respond instantaneously to the applied field, and causality considerations lead to the Kramers–Kronig relations.

If the polarization P is not linearly proportional to the electric field E, the medium is termed nonlinear and is described by the field of nonlinear optics. To a good approximation (for sufficiently weak fields, assuming no permanent dipole moments are present), P is usually given by a Taylor series in E whose coefficients are the nonlinear susceptibilities:

where  is the linear susceptibility,

is the linear susceptibility,  is the second-order susceptibility (describing phenomena such as the Pockels effect, optical rectification and second-harmonic generation), and

is the second-order susceptibility (describing phenomena such as the Pockels effect, optical rectification and second-harmonic generation), and  is the third-order susceptibility (describing third-order effects such as the Kerr effect and electric field-induced optical rectification).

is the third-order susceptibility (describing third-order effects such as the Kerr effect and electric field-induced optical rectification).

In ferroelectric materials, there is no one-to-one correspondence between P and E at all because of hysteresis.

Polarization density in Maxwell's equations

The behavior of electric fields (E and D), magnetic fields (B, H), charge density (ρ) and current density (J) are described by Maxwell's equations in matter.

Relations between E, D and P

In terms of volume charge densities, the free charge density  is given by

is given by

where  is the total charge density. By considering the relationship of each of the terms of the above equation to the divergence of their corresponding fields (of the electric displacement field D, E and P in that order), this can be written as:[9]

is the total charge density. By considering the relationship of each of the terms of the above equation to the divergence of their corresponding fields (of the electric displacement field D, E and P in that order), this can be written as:[9]

Here ε0 is the electric permittivity of empty space. In this equation, P is the (negative of the) field induced in the material when the "fixed" charges, the dipoles, shift in response to the total underlying field E, whereas D is the field due to the remaining charges, known as "free" charges[5] .[10] In general, P varies as a function of E depending on the medium, as described later in the article. In many problems, it is more convenient to work with D and the free charges than with E and the total charge.[1]

Time-varying Polarization Density

When the polarization density changes with time, the time-dependent bound-charge density creates a polarization current density of

so that the total current density that enters Maxwell's equations is given by

where Jf is the free-charge current density, and the second term is the magnetization current density (also called the bound current density), a contribution from atomic-scale magnetic dipoles (when they are present).

Polarization ambiguity

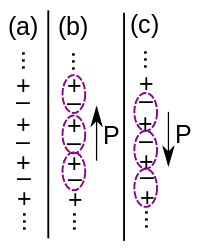

The polarization inside a solid is not, in general, uniquely defined: It depends on which electrons are paired up with which nuclei.[11] (See figure.) In other words, two people, Alice and Bob, looking at the same solid, may calculate different values of P, and neither of them will be wrong. Alice and Bob will agree on the microscopic electric field E in the solid, but disagree on the value of the displacement field  . They will both find that Gauss's law is correct (

. They will both find that Gauss's law is correct ( ), but they will disagree on the value of

), but they will disagree on the value of  at the surfaces of the crystal. For example, if Alice interprets the bulk solid to consist of dipoles with positive ions above and negative ions below, but the real crystal has negative ions as the topmost surface, then Alice will say that there is a negative free charge at the topmost surface. (She might view this as a type of surface reconstruction).

at the surfaces of the crystal. For example, if Alice interprets the bulk solid to consist of dipoles with positive ions above and negative ions below, but the real crystal has negative ions as the topmost surface, then Alice will say that there is a negative free charge at the topmost surface. (She might view this as a type of surface reconstruction).

On the other hand, even though the value of P is not uniquely defined in a bulk solid, variations in P are uniquely defined.[11] If the crystal is gradually changed from one structure to another, there will be a current inside each unit cell, due to the motion of nuclei and electrons. This current results in a macroscopic transfer of charge from one side of the crystal to the other, and therefore it can be measured with an ammeter (like any other current) when wires are attached to the opposite sides of the crystal. The time-integral of the current is proportional to the change in P. The current can be calculated in computer simulations (such as density functional theory); the formula for the integrated current turns out to be a type of Berry's phase.[11]

The non-uniqueness of P is not problematic, because every measurable consequence of P is in fact a consequence of a continuous change in P.[11] For example, when a material is put in an electric field E, which ramps up from zero to a finite value, the material's electronic and ionic positions slightly shift. This changes P, and the result is electric susceptibility (and hence permittivity). As another example, when some crystals are heated, their electronic and ionic positions slightly shift, changing P. The result is pyroelectricity. In all cases, the properties of interest are associated with a change in P.

Even though the polarization is in principle non-unique, in practice it is often (not always) defined by convention in a specific, unique way. For example, in a perfectly centrosymmetric crystal, P is usually defined by convention to be exactly zero. As another example, in a ferroelectric crystal, there is typically a centrosymmetric configuration above the Curie temperature, and P is defined there by convention to be zero. As the crystal is cooled below the Curie temperature, it shifts gradually into a more and more non-centrosymmetric configuration. Since gradual changes in P are uniquely defined, this convention gives a unique value of P for the ferroelectric crystal, even below its Curie temperature.

Another problem in the definition of P is related to the arbitrary choice of the "unit volume", or more precisely to the system's scale

.[5]

For example, at microscopic scale a plasma can be regarded as a gas of free charges,

thus P should be zero. On the contrary, at a macroscopic scale the same plasma

can be described as a continuous medium, exhibiting a permittivity  and thus a net polarization P

and thus a net polarization P .

.

See also

References and notes

- 1 2 Introduction to Electrodynamics (3rd Edition), D.J. Griffiths, Pearson Education, Dorling Kindersley, 2007, ISBN 81-7758-293-3

- 1 2 McGraw Hill Encyclopaedia of Physics (2nd Edition), C.B. Parker, 1994, ISBN 0-07-051400-3

- 1 2 3 4 5 Irodov, I.E. (1986). Basic Laws of Electromagnetism. Mir Publishers, CBS Publishers & Distributors. ISBN 81-239-0306-5

- ↑ Matveev. A. N. (1986). Electricity and Magnetism. Mir Publishers.

- 1 2 3 C.A. Gonano; R.E. Zich; M. Mussetta (2015). "Definition for Polarization P and Magnetization M Fully Consistent with Maxwell's Equations" (PDF). Progress In Electromagnetics Research B 64: 83–101.

- ↑ Based upon equations from Gray, Andrew (1888). The theory and practice of absolute measurements in electricity and magnetism. Macmillan & Co. pp. 126–127., which refers to papers by Sir W. Thomson.

- 1 2 Feynman, R.P.; Leighton, R.B. and Sands, M. (1964) Feynman Lectures on Physics: Volume 2, Addison-Wesley, ISBN 0-201-02117-X

- ↑ Electromagnetism (2nd Edition), I.S. Grant, W.R. Phillips, Manchester Physics, John Wiley & Sons, 2008, ISBN 978-0-471-92712-9

- ↑ Saleh, B.E.A.; Teich, M.C. (2007). Fundamentals of Photonics. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-471-35832-9.

- ↑ A. Herczynski (2013). "Bound charges and currents" (PDF). American Journal of Physics 81 (3): 202–205.

- 1 2 3 4 Resta, Raffaele (1994). "Macroscopic polarization in crystalline dielectrics: the geometric phase approach" (PDF). Rev. Mod. Phys. 66: 899. Bibcode:1994RvMP...66..899R. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.66.899. See also: D Vanderbilt, Berry phases and Curvatures in Electronic Structure Theory, an introductory-level powerpoint.