Frederick William Koko Mingi VIII of Nembe

King Frederick William Koko, Mingi VIII of Nembe (1853–1898), known as King Koko and King William Koko, was an African ruler of the Nembe Kingdom (also known as Nembe-Brass) in the Niger Delta, now part of southern Nigeria.

A Christian when chosen as king of Nembe in 1889, Koko's attack on a Royal Niger Company trading post in January 1895 led to reprisals by the British in which his capital was sacked. Following a report on the Nembe uprising by Sir John Kirk which was published in March 1896, Koko was offered a settlement of his grievances but found the terms unacceptable, so was deposed by the British. He died in exile in 1898.

Life

An Ijaw, Koko was a convert to Christianity who later returned to the local traditional religion.[1] Before becoming king (amanyanabo),[2] he had served as a Christian schoolteacher, and in 1889 this helped him in his rise to power. The leading chiefs of Nembe, including Spiff, Samuel Sambo, and Cameroon, were all Christians, and after having ordered the destruction of Juju houses a large part of their reason for choosing Koko as king in succession to King Ockiya was that he was a fellow-Christian.[1] However, there was at the same time a coparcenary king, the elderly Ebifa, who ruled at Bassambiri and was Commander-in-Chief until his death in 1894.[3]

With the settlement of European traders on the coast, Nembe had engaged in trade with them, but it was poorer than its neighbours Bonny and Calabar.[4] Since 1884, Nembe had found itself included in the area declared by the British as the Oil Rivers Protectorate, within which they claimed control of military defence and external affairs. Nembe was the centre of an important trade in palm oil, and it had refused to sign a treaty proposed by the British, opposing the Royal Niger Company's aim of bringing all trade along the kingdom's rivers into its own hands.[5]

By the 1890s, there was intense resentment of the Company's treatment of the people of the Niger delta and of its aggressive actions to exclude its competitors and to monopolize trade, denying the men of Nembe the access to markets which they had long enjoyed.[6][7] As king, Koko aimed to resist these pressures and tried to strengthen his hand by forming alliances with the states of Bonny and Okpoma. He renounced Christianity[8] and in January 1895, after the death of Ebifa, he threw caution to the winds and led more than a thousand men in a dawn raid on the Royal Niger Company's headquarters at Akassa.[9] Arriving on 29 January with between forty and fifty canoes,[6] equipped with heavy guns, Koko captured the base with the loss of some forty lives, including twenty-four Company employees, destroyed warehouses and machinery, and took about sixty white men hostage, as well as carrying away a large quantity of booty, including money, trade goods, ammunition and a quick-firing gun.[2][10] Koko then sought to negotiate with the Company for the release of the hostages, his price being a return to free trading conditions,[11] and on 2 February he wrote to Sir Claude MacDonald, the British consul-general, that he had no quarrel with the Queen but only with the Niger Company. MacDonald noted of what Koko said of the Company that it was "complaints it had been my unpleasant duty to listen to for the last three and a half years without being able to gain for them any redress".[6] Despite this, the British refused Koko's demands, and more than forty of the hostages were then ceremoniously eaten.[12][13] On 20 February the Royal Navy counter-attacked. Koko's city of Nembe was razed and some three hundred of his people were killed.[6] Many more of his people died from a severe outbreak of smallpox.[5]

Rear Admiral Sir Frederick Bedford, who had led the British forces against Koko, sent the following telegram to the Admiralty from Brass on 23 February:[14]

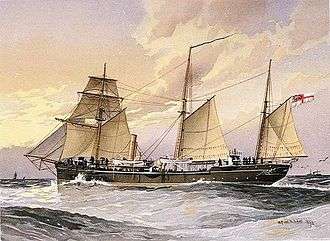

Left Brass on February 20, with HMS Widgeon, HMS Thrush, two steamers of the Niger Company, and the boat of HMS St George, with marines and Protectorate troops; anchored off Nimbi Creek and seized Sacrifice Island the same afternoon; the approach was obstructed by stockades, which are also under construction on the island; 25 war canoes came out and opened an ineffectual fire; three were sunk, and the rest retired. On February 21 the intricate channels were buoyed and the creek reconnoitred. At daybreak on February 22 we attacked, and, after an obstinate defence of a position naturally difficult, a landing was gallantly effected and Nimbi completely burned. In the evening the force was withdrawn, after King Koko's and other chiefs' houses were destroyed.[14]

Bedford sent a further despatch from Brass on 25 February:[14]

Fishtown destroyed today. Brass chiefs and people implicated in attack Akassa have now been punished. No more casualties. Wounded progressing favourably. No further operations contemplated. Consul-General concurs. I am leaving for Loanda to-morrow evening. Two ships remain in vicinity for present.[14]

On 23 March Sir Claude MacDonald arrived at Brass in his yacht Evangeline towing sixteen of Koko's war canoes which had been surrendered, but the king himself had not been captured.[15] Towards the end of April 1895, the area returned to business as usual, with MacDonald fining the men of Brass £500, an amount which sympathetic traders on the river volunteered to pay. Koko assured the British that his part in the rising had been exaggerated, and returned several cannon and a machine-gun looted from Akassa. There was then an exchange of prisoners.[16] Public opinion in Britain came down against the Royal Niger Company and its director George Goldie, who was seen as having goaded Koko into hostilities.[13] The Colonial Office commissioned the explorer and anti-slavery campaigner Sir John Kirk to write a report on the events at Akassa and Brass,[12] and in August Koko came to Brass to meet MacDonald, who was about to sail for England, but quickly took to the bush again. On MacDonald's arrival at Liverpool he told reporters that the people of Nembe-Brass were waiting for the outcome of Kirk's report.[17]

Sir John Kirk's Report was presented to both Houses of Parliament by command of Her Majesty the Queen in March 1896.[18] One key finding was that forty-three of Koko's prisoners had been murdered and eaten.[19] In April 1896 Koko refused the terms of a settlement offered to him by the British and was declared an outlaw. Reuters reported that the Niger stations were strongly defended in preparation for a possible new attack.[20] However, no attack came. A reward of £200 was unsuccessfully offered for Koko,[6] who was forced to flee from the British, hiding in remote villages.[21]

On 11 June 1896, in reply to a question by Sir Charles Dilke in the House of Commons, George Nathaniel Curzon, Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, said

The Commissioner has in his possession a plan prepared by the chairman of the Royal Niger Company for the admitting of the Brass men into markets hitherto closed to them on the Niger. It was, however, subject to acceptance by King Koko, which it has been impossible to obtain as, since the attack on Akassa and subsequent cannibalism of captives in his capital, he has declined to meet any of the British authorities, including Sir John Kirk. In consequence of this behaviour he has been deposed. The settlement is now dependent upon the organization of a new native government in Brass, and will, it is hoped, very soon be arrived at.[22]

Koko fled to Etiema, a remote village in the hinterland, where he died in 1898 in a suspected suicide. The next year, the charter of the Royal Niger Company was revoked, an act seen as partly a consequence of the short war with Koko,[23] and with effect from 1 January 1900 the Company sold all its possessions and concessions in Africa to the British government for £865,000, considered to be a very low price.[24]

In popular culture

In his Doctor Dolittle books, Hugh Lofting (1886–1947) created the West African kingdom of Fantippo, ruled over by a king named Koko.[25] Before his encounters with Dolittle, the fictional King Koko had sometimes made war on others and had sold some of his prisoners as slaves.[26] The main stated purpose of the British in the Anglo-Aro War of 1901–1902 was to suppress the slave trade still being carried on by some African states in what is now Nigeria.[27]

Further reading

- Ebiegberi Joe Alagoa, The Akassa Raid, 1895 (Ibadan University Press, 1960)

- Ebiegberi Joe Alagoa, The small brave city-state: a history of Nembe-Brass in the Niger Delta (Ibadan University Press and University of Wisconsin Press, 1964)

- Ebiegberi Joe Alagoa, Beke you mi: Nembe against the British Empire (Onyoma Research Publications, 2001) ISBN 9783507567

- Livingston Borobuebi Dambo, Nembe: the divided kingdom (Paragraphics, 2006)

- Sir John Kirk, Report by Sir John Kirk on the disturbances at Brass (Colonial Office, 1896)

Notes

- 1 2 G. O. M. Tasie, Christian missionary enterprise in the Niger Delta 1864-1918 (1978), p. 61

- 1 2 Toyin Falola, Ann Genova, Historical Dictionary of Nigeria (Scarecrow Press, 2009), p. 67

- ↑ Livingston Borobuebi Dambo, Nembe: the divided kingdom (Paragraphics, 2006), pp. 142, 204, 368: "All these are classical examples of the rotation of power between the two kings in Nembe signifying the coparcenery of Nembe. Even at old age King Ebifa did not relinquish his authority as the Commander-in-Chief to King Koko."

- ↑ G. I. Jones, The trading states of the oil rivers: a study of political development in Eastern Nigeria (James Currey Publishers, 2001, ISBN 0-85255-918-6), p. 85ff

- 1 2 Mogens Herman Hansen, A comparative study of thirty city-state cultures: an investigation (Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskab, 2000, ISBN=87-7876-177-8), p. 534

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sir W. Geary, Nigeria under British Rule (1927), p. 196

- ↑ Augustine A. Ikein, Diepreye S. P. Alamieyeseigha, Steve S. Azaiki, Oil, Democracy, and the Promise of True Federalism in Nigeria (2008), p. 4

- ↑ Dambo (2006), p. 589

- ↑ Falola & Genova (2009), p. 197

- ↑ Sam C. Ukpabi, Mercantile soldiers in Nigerian history: a history of the Royal Niger Company army, 1886-1900 (Gaskiya, 1987), pp. 150-152, including footnote 38

- ↑ Alfred Vingoe 1869-1954 A Full and Varied Life at tripod.com, accessed 25 September 2012

- 1 2 Sir John Kirk, Report by Sir John Kirk on the Disturbances at Brass: C. 7977 (Great Britain: Colonial Office, 1896, 26 pages)

- 1 2 Toyin Falola, Matthew M. Heaton, A History of Nigeria (Cambridge University Press, 2008) p. 102

- 1 2 3 4 'The Fighting on the Niger', from The Times of London, issue 34510 dated Tuesday, February 26, 1895, p. 5

- ↑ 'West Coast of Africa' in The Times of London, issue 34553 dated Wednesday, April 17, 1895, p. 3

- ↑ 'The Brass Rising' in The Times of London, Issue 34561 dated Friday, April 26, 1895, p. 5

- ↑ 'Sir Claude M. MacDonald on West Africa' in The Times of London, issue 34662 dated Thursday, August 22, 1895, p. 3

- ↑ Andrew Herman Apter, The Pan-African Nation: Oil and the Spectacle of Culture in Nigeria (2005), p. 298

- ↑ Geary (1927), p. 195

- ↑ 'West Africa', The Times of London, issue 34869 dated Monday, April 20, 1896, p. 5

- ↑ J. F. Ade Ajayi, Africa in the Nineteenth Century Until the 1880s, vol. 6 (Unesco International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of Africa, 1989), p. 734

- ↑ 'House of Commons: The Niger Company's Markets' in The Times of London, issue 34915 dated Friday, June 12, 1896, p. 6

- ↑ Mark R. Lipschutz, R. Kent Rasmussen, Dictionary of African historical biography (1989), p. 112

- ↑ Paul Samuel Reinsch, Colonial government: an introduction to the study of colonial institutions (Macmillan Company, 1916) p. 157

- ↑ Hugh Lofting, Doctor Dolittle's Post Office (1924), Doctor Dolittle and the Secret Lake (1948)

- ↑ Donnarae MacCann, Gloria Woodard, The Black American in books for children: readings in racism (1985): "The pre-Dolittle years of King Koko's reign were not so "golden." In those days he occasionally made war on other African tribes and took many prisoners. Some he sold as slaves to white traders."

- ↑ Adiele Eberechukwu Afigbo, The Abolition of the Slave Trade in Southeastern Nigeria, 1885-1950 (University of Rochester Press, 2006), p. 44