Fraser Canyon

Coordinates: 49°38′00″N 121°25′00″W / 49.63333°N 121.41667°W

.jpg)

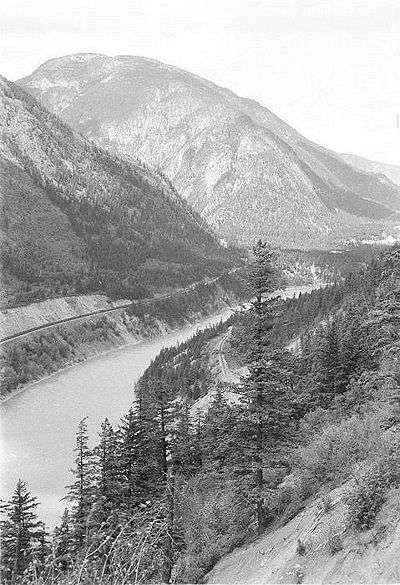

The Fraser Canyon is an 84 km landform of the Fraser River where it descends rapidly through narrow rock gorges in the Coast Mountains en route from the Interior Plateau of British Columbia to the Fraser Valley. Colloquially, the term "Fraser Canyon" is often used to include the Thompson Canyon from Lytton to Ashcroft, since they form the same highway route which most people are familiar with, although it is actually reckoned to begin above Williams Lake, British Columbia at Soda Creek Canyon near the town of the same name.

Geology

The canyon was formed during the Miocene period (23.7–5.3 million years ago) by the river cutting into the uplifting Interior Plateau. From the northern Cariboo to Fountain, the river follows the line of the huge Fraser Fault, which runs on a north-south axis and meets the Yalakom Fault a few miles downstream from Lillooet. Exposures of lava flows are present in cliffs along the Fraser Canyon. They represent volcanic activity in the southern Chilcotin Group during the Pliocene period and the volcanic vents of their origins have not been discovered.

Geography

(the valley coming in at left)

The canyon extends 270 kilometres (170 mi) north of Yale to the confluence of the Chilcotin River. Its southern stretch is a major transportation corridor to the Interior from "the Coast", with the Canadian National and Canadian Pacific Railways and the Trans-Canada Highway carved out of its rock faces, with many of the canyon's side-crevasses spanned by bridges and trestles. Prior to the double-tracking of those railways and major upgrades to Highway 1 (the Trans Canada Highway), travel through the canyon was even more precarious than it is now. During the frontier era it was a major obstacle between the Lower Mainland and the Interior Plateau, and the slender trails along its rocky walls - many of them little better than notches cut into granite, with a few handholds - were compared to goat-tracks.

North of Lytton, it is followed by BC Highway 12, then from Lillooet to Pavilion by BC Hwy 99 (the farther end of the Sea-to-Sky Highway, though not carrying that name in this area). The British Columbia Railway (the BC Railway is now owned and operated by the CN) line follows the same stretch of canyon from Lillooet to just beyond Pavilion. Between there and the mouth of the Chilcotin River there are only rough ranching roads, and the terrain is a mix of canyon depths flanked by arid benchland and high plateau. Between Pavilion and Lillooet, the river's gorge is at its maximum depth, with the river throttled through a series of narrow gorges flanked by high cliffs, though still flanked above those cliffs by wide benchlands which stand on the foreshoulder of the mountain ranges flanking the gorge.

Hells Gate

At Hells Gate, near Boston Bar, the canyon walls rise about 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) above the rapids. Fish ladders along the river's side permit migrating salmon to bypass a rockslide that diverted the river during the blasting of the Canadian Northern Railway line in 1913. The area around Hell's Gate carries the name Black Canyon, which may either be a reference to the colour of the rocks when it rains, or the name of a community built on the cliffsides here during the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush. Today there is a specially-built air-tram, like the kind used in ski resorts, which takes tourists down to Hells Gate, where visitors may view the fish ladders as well as the boiling rush of the Fraser's waters. A set of tourist pavilions with shops and café now occupies the site of the workmen's housing seen in the accompanying image.

At Siska, a few minutes south of Lytton, there are the Cisco bridges—a pair of railway bridges at the throat of a rocky gorge. From south to north, the Canadian Pacific has been on the west side of the canyon, while the Canadian National has been on the east side. Here Cisco (Skiska), the two railways switch sides: the CP—(520-foot (160 m))-long truss bridge—crosses to the east, the CN—on a 810-foot (250 m) steel-arched bridge over the CP—is now on the west. The two railways now have an agreement to allow directional running through the canyon as far as Basque. All eastbound trains—CN, CP, and Via Rail's eastbound Canadian—run on the CP line. All westbound trains—CN, CP, Via Rail's westbound Canadian—use the CN tracks.

Upper Fraser Canyon

Just north of Lillooet, narrow rock ledges choke the river just at the confluence of the lower canyon of the Bridge River, forming an obstacle to migrating fish that has made this spot the busiest aboriginal fishing site on the river, from ancient times to the present. Concentrations of First Nations people here, from all tribes of the Interior, were believed to have been in excess of 10,000.

Sub-canyons

Many stretches of the Fraser are named in their own right, starting with the Little Canyon between Yale and Spuzzum, which is officially the lowest reach of the Fraser Canyon (although in regional terms Hope, 20 miles (32 km) farther south, is considered a canyon town and to be the southern outlet of the canyon because the highway became more difficult from that point; the river is navigable to Yale). Between the Spuzzum and Boston Bar was known in the gold rush as the Big Canyon or Black Canyon;[1] there are several named subcanyons of the Big Canyon, most famously Hells Gate Canyon (in some descriptions the Black Canyon is below Hell's Gate). Above the Big Canyon there are the Lillooet Canyon, Fountain Canyon, Glen Fraser Canyon, Moran Canyon, High Bar Canyon, French Bar Canyon and more all the way up to Soda Creek Canyon near Quesnel. Upstream from there the river flows in wider country, but in the Robson Valley between Prince George and Tête Jaune Cache, the river enters the Grand Canyon of the Fraser. The Black Canyon was the site of a shantytown of the same name, much of which was on catwalks on the ramparts of its dark-rock cliffs.

Nearly all tributaries of the Fraser have canyons of varying scale; the few exceptions include the Pitt and the Chilliwack in the Lower Fraser Valley. The Thompson Canyon, from Lytton to Ashcroft, is a sequence of large canyons of its own, some of them also named, although most British Columbians and travellers think of it as part of the Fraser Canyon. Other important canyons on tributaries include Coquihalla Canyon, the Bridge River Canyon, Seton Canyon and adjacent Cayoosh Canyon, Pavilion Canyon, Vermilion Canyon (Slok Creek) and Churn Creek Canyon. The Chilcotin River also has several subcanyons, as does the Chilko River, notably Lava Canyon and another Black Canyon.

Upper canyons

There are other canyons on the Fraser that are not considered part of the canyon, notably at Soda Creek, between Williams Lake and Prince George. The official but comparatively diminutive Grand Canyon of the Fraser is in the river's upper stretch through the Rocky Mountain Trench, about 115 km (71 mi) upstream from Prince George and about 20 km (12 mi) upstream from the Fraser's confluence with the Bowron River. Despite its name, the Grand Canyon of the Fraser is only one treacherous switchback rapid in a shallow rock gorge, and it has neither the roughness of water nor the depth and severity of canyon as is found in the area south from Big Bar to Lillooet or between Boston Bar and Yale.

Almost all of the rivers and creeks feeding the Fraser from Williams Lake south have their own canyons which open onto the Fraser, or are just up side-valleys a few miles. These include Marble Canyon, Churn Creek, the Chilcotin River, the Bridge River, Seton Lake and Cayoosh Creek, the Stein River, the Nahatlatch River, the Coquihalla River and the innumerable smaller creeks flanking the river between Kanaka Bar and Yale.

Tunnels

The Fraser Canyon Highway Tunnels were constructed from the spring of 1957 to 1964 as part of the Trans-Canada Highway project. There are seven tunnels in total, the shortest being about 57 metres (187 ft); the longest, however, is about 610 metres (2,000 ft) and is one of North America's longest. They are situated between Yale and Boston Bar.

In order from south to north, they are: Yale (completed 1963), Saddle Rock (1958), Sailor Bar (1959), Alexandra (1964), Hell's Gate (1960), Ferrabee (1964) and China Bar (1961). The Hell's Gate tunnel is the only tunnel that does not have lights, while the China Bar tunnel is the only tunnel that requires ventilation.

The China Bar and Alexandra tunnels have warning lights that are activated by cyclists before they enter the tunnels. This was required because the tunnels are curved. It is expected that the Ferrabee tunnel will get the same warning lights as it too is curved.

History

At the mouth of the Canyon, an archeological site documents the presence of the Stó:lō people in the area from the early Holocene period, 8,000 to 10,000 years ago after the retreat of the Fraser Glacier. Research farther upriver at the Keatley Creek Archaeological Site, near Pavilion, is dated to 8000 BP, when a huge lake filled what is now the canyon above Lillooet, created by a slide a few miles south of the present-day town.

During the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush of 1858–1860, 10,500 miners and an untold number of hangers-on populated its banks and towns. The Fraser Canyon War and the series of events known as McGowan's War occurred during the gold rush. Other important histories connected with the Canyon include the building of the Cariboo Wagon Road and the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway.

The river is navigable between Boston Bar and Lillooet and also between Big Bar Ferry and Prince George and beyond, although rapids at Soda Canyon and elsewhere were still difficult waters for the many steamboats which piloted the river in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Skuzzy was the first sternwheeler to make it through the rapids, which was built with multiple-compartment hulls to preserve it from sinking from rock damage. It was used to haul equipment and supplies during the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway.

With the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway in the 1880s came the destruction of key portions of the Cariboo Wagon Road, as there was no room for both railway and road on the narrow, steep mountainsides above the river. As a result, the towns of Lytton and Boston Bar were cut off from road access with the rest of the province, other than by the difficult wagon road to Lillooet via Fountain. During the automotive age and following the construction of the Canadian Northern Railway in 1904–05, a newer version of the road was built through the canyon. The Fraser Canyon Highway was surveyed in 1920 and constructed in 1924–25 with a through-route available after the completion of the (second) Alexandra Suspension Bridge in 1926. This was known as the Cariboo Highway and Highway 1 until the construction and designation of the Trans-Canada Highway (circa-1962).[2]

See also

Rivers

- Anderson River

- Bridge River

- Chilcotin River

- Churn Creek

- Coquihalla River

- Fraser River

- Nahatlatch River

- Thompson River

- Stein River

Towns and localities

- Riske Creek

- Big Bar

- Boston Bar-North Bend

- Emory Creek

- Fountain

- Hill's Bar

- Hope

- Jesmond

- Kanaka Bar

- Lillooet

- Lytton

- Pavilion

- Spuzzum

- Yale

Other

- Big Bar Ferry

- Dewdney Trail

- Fountain

- Hudson's Bay Brigade Trail

- Marble Canyon

- Nlaka'pamux

- Pavilion

- Skagit Trail

- St'at'imc

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fraser Canyon. |

References

- ↑ BCGNIS entry "Black Canyon"

- ↑ Harris, Lorraine (1984). Fraser Canyon, from Cariboo road to super highway. Surrey, B.C.: Hancock House. ISBN 088839182X.

Further reading

- Prentiss, Anna Marie; Kuijt, Ian (2012). People of the middle Fraser Canyon an archaeological history. Vancouver: UBC Press. ISBN 9780774821704.

- Waite, Donald E. (1988). The Fraser Canyon story. Surrey, B.C.: Hancock House. ISBN 9780888392046.

- York, Annie (2011). Spuzzum: Fraser Canyon Histories 1808-1939. UBC Press. ISBN 9780774841887.