Franklin Pierce Adams

- For other people named Franklin Adams, see the Franklin Adams navigation page

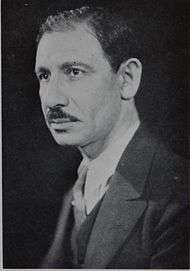

Franklin Pierce Adams (November 15, 1881 – March 23, 1960) was an American columnist, well known by his initials F.P.A., and wit, best known for his newspaper column, "The Conning Tower", and his appearances as a regular panelist on radio's Information Please. A prolific writer of light verse, he was a member of the Algonquin Round Table of the 1920s and 1930s.

New York newspaper columnist

Adams was born Franklin Leopold Adams to Moses and Clara Schlossberg Adams in Chicago on November 15, 1881. He changed his middle name to "Pierce" when he had a Jewish confirmation ceremony at age 13.[1] Adams graduated from the Armour Scientific Academy (now Illinois Institute of Technology) in 1899, attended the University of Michigan for one year and worked in insurance for three years.

Signing on with the Chicago Journal in 1903, he wrote a sports column and then a humor column, "A Little about Everything". The following year he moved to the New York Evening Mail, where he worked from 1904 to 1913 and began his column, then called "Always in Good Humor", which used reader contributions.

During his time on the Evening Mail, Adams wrote what remains his best known work, the poem Baseball's Sad Lexicon, a tribute to the Chicago Cubs double play combination of "Tinker to Evers to Chance". In 1911, he added a second column, a parody of Samuel Pepys's Diary, with notes drawn from F.P.A.'s personal experiences. In 1914, he moved his column to the New-York Tribune, where it was famously retitled "The Conning Tower."

During World War I, Adams was in the U.S. Army, serving in military intelligence and also writing a column, "The Listening Post", for Stars and Stripes editor Harold Ross. After the war, the so-called "comma-hunter of Park Row"[2] (for his knowledge of the language) returned to New York and the Tribune. He moved to the New York World in 1922, and his column appeared there until the paper merged with the inferior New York Telegram in 1931. He returned to his old paper, by then called the New York Herald Tribune, until 1937, and finally moved to the New York Post, where he ended his column in September 1941.

During its long run, "The Conning Tower" featured contributions from such writers as Robert Benchley, Edna Ferber, Moss Hart, George S. Kaufman, Edna St. Vincent Millay, John O'Hara, Dorothy Parker and Deems Taylor. Having one's work published in "The Conning Tower" was enough to launch a career, as in the case of Dorothy Parker and James Thurber. Parker quipped, "He raised me from a couplet." Parker dedicated her 1936 publication of collected poems, Not So Deep as a Well, to F.P.A. Many of the poems in that collection were originally published in "The Conning Tower".

Much later, the writer E. B. White freely admitted his sense of awe: "I used to walk quickly past the house in West 13th Street between Sixth and Seventh where F.P.A. lived, and the block seemed to tremble under my feet—the way Park Avenue trembles when a train leaves Grand Central."[3]

Adams is credited with coining the term "aptronym" for last names that fit a person's career or job title, although it was later refined to "aptonym" by Frank Nuessel in 1992.

Satires

- No Sirree!, staged for one night only in April 1922, was a take-off of a then-popular European touring revue called La Chauve-Souris directed by Nikita Balieff.[4]

- Robert Benchley is often credited as the first person to suggest the parody of Balieff's group.[5]

- No Sirree! had its genesis at the studio of Neysa McMein, which served as something of a salon for Round Tablers away from the Algonquin. Acts included: "Opening Chorus" featuring Woollcott, Toohey, Kaufman, Connelly, Adams, and Benchley with violinist Jascha Heifetz providing offstage, off-key accompaniment; "He Who Gets Flapped," a musical number featuring the song "The Everlastin' Ingenue Blues" written by Dorothy Parker and performed by Robert Sherwood accompanied by "chorus girls" including Tallulah Bankhead, Helen Hayes, Ruth Gillmore, Lenore Ulric, and Mary Brandon; "Zowie, or the Curse of an Akins Heart"; "The Greasy Hag, an O'Neill Play in One Act" with Kaufman, Connelly and Woollcott; and "Mr. Whim Passes By - An A. A. Milne Play."[6]

- F.P.A. often included parodies in his column. His satire of Edgar Allan Poe's poem "Annabel Lee" was later collected in his book Something Else Again (1910):

- Soul Bride Oddly Dead in Queer Death Pact

- High-Born Kinsman Abducts Girl from Poet-Lover—Flu Said to Be Cause of Death—Grand Jury to Probe

- Annabel L. Poe of 1834½ 3rd Ave., the beautiful young fiancee of Edmund Allyn Poe, a magazine writer from the South, was found dead early this morning on the beach off E. 8th Street. Poe seemed prostrated and, questioned by the police, said that one of her aristocratic relatives had taken her to the "seashore," but that the cold winds had given her "flu," from which she never "rallied." Detectives at work on the case believe, they say, that there was a suicide compact between the Poes and that Poe also intended to do away with himself. He refused to leave the spot where the woman's body had been found.

Radio

As a panelist on radio's Information Please (1938–48), he was the designated expert on poetry, old barroom songs and Gilbert and Sullivan, which he always referred to as Sullivan and Gilbert. A running joke on the show was that his stock answer for quotes that he didn't know was that Shakespeare was the author. (Perhaps that was a running gag: Information Please's creator/producer Dan Golenpaul auditioned Adams for the job with a series of sample questions, starting with: "Who was the Merchant of Venice?" Adams: "Antonio." Golenpaul: "Most people would say 'Shylock.'" Adams: "Not in my circle.")[7] John Kieran was the real Shakespearean expert and could quote from his works at length.

A translator of Horace and other classical authors, F.P.A. also collaborated with O. Henry on Lo, a musical comedy.

Film portrayal

Adams was portrayed by the actor Chip Zien in the film Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle (1994).[8]

Bibliography

Books

His books include In Cupid's Court (1902), Tobogganning on Parnassus (1911), In Other Words (1912) and Answer This One (a 1927 trivia book with Harry Hansen). The two-volume The Diary of Our Own Samuel Pepys, collected from his newspaper columns, was published in 1935 by Simon and Schuster. The Melancholy Lute (1936) featured Adams' selections from three decades of his work.

Contributions to The New Yorker (partial list)[9]

| Title | Department | Volume/Part | Date | Page(s) | Subject(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Story Scenarios | 1/1 | 21 February 1925 | 19 | ||

| A Day in the Courts | 2/41 | 9 October 1926 | 29 | ||

| Grant | The Talk of the Town | 3/10 | 5 March 1927 | 20 | |

| Mot (with Harold Ross & James Thurber) | The Talk of the Town | 3/18 | 30 April 1927 | 19 | |

| Another (with E.B. White) | The Talk of the Town | 3/19 | 7 May 1927 | 19 | |

Quotes

- "I find that a great part of the information I have was acquired by looking up something and finding something else on the way."

- "To err is human; to forgive, infrequent."

- "Elections are won by men and women chiefly because most people vote against somebody rather than for somebody."

See also

References

- ↑ Ashley, Sally. F.P.A.: The Life and Times of Franklin Pierce Adams. Beaufort, 1986. p. 25.

- ↑ Ashley, p. 13.

- ↑ White, E.B. Here Is New York. Harper & Bros., 1949. p. 32.

- ↑ Kunkel, Thomas (1995). Genius in Disguise: Harold Ross of The New Yorker. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers (paperback). p. 81. ISBN 0-7867-0323-7.

- ↑ Altman, Billy (1997). Laughter's Gentle Soul: The Life of Robert Benchley. New York: W.W. Norton. p. 199. ISBN 0-393-03833-5.

- ↑ Altman, p. 203

- ↑ Ashley, p. 211.

- ↑ Full cast and crew for Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle (1994) at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ http://www.newyorker.com/contributors/franklin-p-adams/all/8

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Franklin Pierce Adams |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1921 Collier's Encyclopedia article about Franklin Pierce Adams. |

- Works by Franklin Pierce Adams at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Franklin Pierce Adams at Internet Archive

- 82 poems by FPA

- Something Else Again (Doubleday, 1920)

- Poet's Corner: "Something Else Again

- Tobogganing on Parnassus (1911): Works by Franklin Pierce Adams at Project Gutenberg

- Index entry for Franklin P. Adams at Poets' Corner

- Franklin Pierce Adams at University of Toronto Libraries

|