Francium

| General properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name, symbol | francium, Fr | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pronunciation |

/ˈfrænsiəm/ FRAN-see-əm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Francium in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 87 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group, block | group 1 (alkali metals), s-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Element category | alkali metal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight (Ar) | (223) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Rn] 7s1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

per shell | 2, 8, 18, 32, 18, 8, 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase | solid presumably | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | ? 300 K (27 °C, 80 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | ? 950 K (677 °C, 1250 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density near r.t. | 1.87 g/cm3 (extrapolated) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | ca. 2 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | ca. 65 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

vapor pressure (extrapolated)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | +1 (a strongly basic oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 0.7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies | 1st: 393[1] kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 260 pm (extrapolated) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 348 pm (extrapolated) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Miscellanea | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure |

body-centered cubic (bcc)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 15 W/(m·K) (extrapolated) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 3 µΩ·m (calculated) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | Paramagnetic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-73-5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Naming | after France, homeland of the discoverer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery and first isolation | Marguerite Perey (1939) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Most stable isotopes of francium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Francium is a chemical element with symbol Fr and atomic number 87. It used to be known as eka-caesium and actinium K.[note 1] It is the second-least electronegative element, behind only caesium. Francium is a highly radioactive metal that decays into astatine, radium, and radon. As an alkali metal, it has one valence electron.

Bulk francium has never been viewed. Because of the general appearance of the other elements in its periodic table column, it is assumed that francium would appear as a highly reflective metal, if enough could be collected together to be viewed as a bulk solid or liquid. Obtaining such a sample is highly improbable, since the extreme heat of decay (the half-life of its longest-lived isotope is only 22 minutes) would immediately vaporize any viewable quantity of the element.

Francium was discovered by Marguerite Perey in France (from which the element takes its name) in 1939. It was the last element first discovered in nature, rather than by synthesis.[note 2] Outside the laboratory, francium is extremely rare, with trace amounts found in uranium and thorium ores, where the isotope francium-223 continually forms and decays. As little as 20–30 g (one ounce) exists at any given time throughout the Earth's crust; the other isotopes (except for francium-221) are entirely synthetic. The largest amount produced in the laboratory was a cluster of more than 300,000 atoms.[2]

Characteristics

Francium is the most unstable of the naturally occurring elements: its most stable isotope, francium-223, has a half-life of only 22 minutes. In contrast, astatine, the second-least stable naturally occurring element, has a half-life of 8.5 hours.[3] All isotopes of francium decay into astatine, radium, or radon.[3] Francium is also less stable than all synthetic elements up to element 105.[4]

Francium is an alkali metal whose chemical properties mostly resemble those of caesium.[4] A heavy element with a single valence electron,[5] it has the highest equivalent weight of any element.[4] Liquid francium—if created—should have a surface tension of 0.05092 N/m at its melting point.[6] Francium's melting point was calculated to be around 27 °C (80 °F, 300 K).[7] The melting point is uncertain because of the element's extreme rarity and radioactivity. Thus, the estimated boiling point value of 677 °C (1250 °F, 950 K) is also uncertain.

Linus Pauling estimated the electronegativity of francium at 0.7 on the Pauling scale, the same as caesium;[8] the value for caesium has since been refined to 0.79, but there are no experimental data to allow a refinement of the value for francium.[9] Francium has a slightly higher ionization energy than caesium,[10] 392.811(4) kJ/mol as opposed to 375.7041(2) kJ/mol for caesium, as would be expected from relativistic effects, and this would imply that caesium is the less electronegative of the two. Francium should also have a higher electron affinity than caesium and the Fr− ion should be more polarizable than the Cs− ion.[11] The CsFr molecule is predicted to have francium at the negative end of the dipole, unlike all known heterodiatomic alkali metal molecules. Francium superoxide (FrO2) is expected to have a more covalent character than its lighter congeners; this is attributed to the 6p electrons in francium being more involved in the francium–oxygen bonding.[11]

Francium coprecipitates with several caesium salts, such as caesium perchlorate, which results in small amounts of francium perchlorate. This coprecipitation can be used to isolate francium, by adapting the radiocaesium coprecipitation method of Glendenin and Nelson. It will additionally coprecipitate with many other caesium salts, including the iodate, the picrate, the tartrate (also rubidium tartrate), the chloroplatinate, and the silicotungstate. It also coprecipitates with silicotungstic acid, and with perchloric acid, without another alkali metal as a carrier, which provides other methods of separation.[12][13] Nearly all francium salts are water-soluble.[14]

Isotopes

There are 34 known isotopes of francium ranging in atomic mass from 199 to 232.[15] Francium has seven metastable nuclear isomers.[4] Francium-223 and francium-221 are the only isotopes that occur in nature, though the former is far more common.[16]

Francium-223 is the most stable isotope, with a half-life of 21.8 minutes,[4] and it is highly unlikely that an isotope of francium with a longer half-life will ever be discovered or synthesized.[17] Francium-223 is the fifth product of the actinium decay series as the daughter isotope of actinium-227.[18] Francium-223 then decays into radium-223 by beta decay (1149 keV decay energy), with a minor (0.006%) alpha decay path to astatine-219 (5.4 MeV decay energy).[19]

Francium-221 has a half-life of 4.8 minutes.[4] It is the ninth product of the neptunium decay series as a daughter isotope of actinium-225.[18] Francium-221 then decays into astatine-217 by alpha decay (6.457 MeV decay energy).[4]

The least stable ground state isotope is francium-215, with a half-life of 0.12 μs. (9.54 MeV alpha decay to astatine-211):[4] Its metastable isomer, francium-215m, is less stable still, with a half-life of only 3.5 ns.[20]

Applications

Due to its instability and rarity, there are no commercial applications for francium.[21][22][23][18] It has been used for research purposes in the fields of chemistry[24] and of atomic structure. Its use as a potential diagnostic aid for various cancers has also been explored,[3] but this application has been deemed impractical.[22]

Francium's ability to be synthesized, trapped, and cooled, along with its relatively simple atomic structure have made it the subject of specialized spectroscopy experiments. These experiments have led to more specific information regarding energy levels and the coupling constants between subatomic particles.[25] Studies on the light emitted by laser-trapped francium-210 ions have provided accurate data on transitions between atomic energy levels which are fairly similar to those predicted by quantum theory.[26]

History

As early as 1870, chemists thought that there should be an alkali metal beyond caesium, with an atomic number of 87.[3] It was then referred to by the provisional name eka-caesium.[27] Research teams attempted to locate and isolate this missing element, and at least four false claims were made that the element had been found before an authentic discovery was made.

Erroneous and incomplete discoveries

Soviet chemist D. K. Dobroserdov was the first scientist to claim to have found eka-caesium, or francium. In 1925, he observed weak radioactivity in a sample of potassium, another alkali metal, and incorrectly concluded that eka-caesium was contaminating the sample (the radioactivity from the sample was from the naturally occurring potassium radioisotope, potassium-40).[28] He then published a thesis on his predictions of the properties of eka-caesium, in which he named the element russium after his home country.[29] Shortly thereafter, Dobroserdov began to focus on his teaching career at the Polytechnic Institute of Odessa, and he did not pursue the element further.[28]

The following year, English chemists Gerald J. F. Druce and Frederick H. Loring analyzed X-ray photographs of manganese(II) sulfate.[29] They observed spectral lines which they presumed to be of eka-caesium. They announced their discovery of element 87 and proposed the name alkalinium, as it would be the heaviest alkali metal.[28]

In 1930, Fred Allison of the Alabama Polytechnic Institute claimed to have discovered element 87 when analyzing pollucite and lepidolite using his magneto-optical machine. Allison requested that it be named virginium after his home state of Virginia, along with the symbols Vi and Vm.[29][30] In 1934, H.G. MacPherson of UC Berkeley disproved the effectiveness of Allison's device and the validity of this false discovery.[31]

In 1936, Romanian physicist Horia Hulubei and his French colleague Yvette Cauchois also analyzed pollucite, this time using their high-resolution X-ray apparatus.[28] They observed several weak emission lines, which they presumed to be those of element 87. Hulubei and Cauchois reported their discovery and proposed the name moldavium, along with the symbol Ml, after Moldavia, the Romanian province where Hulubei was born.[29] In 1937, Hulubei's work was criticized by American physicist F. H. Hirsh Jr., who rejected Hulubei's research methods. Hirsh was certain that eka-caesium would not be found in nature, and that Hulubei had instead observed mercury or bismuth X-ray lines. Hulubei insisted that his X-ray apparatus and methods were too accurate to make such a mistake. Because of this, Jean Baptiste Perrin, Nobel Prize winner and Hulubei's mentor, endorsed moldavium as the true eka-caesium over Marguerite Perey's recently discovered francium. Perey took pains to be accurate and detailed in her criticism of Hulubei's work, and finally she was credited as the sole discoverer of element 87.[28] All other previous purported discoveries of element 87 were ruled out due to francium's very limited half-life.[29]

Perey's analysis

Eka-caesium was discovered in 1939 by Marguerite Perey of the Curie Institute in Paris, when she purified a sample of actinium-227 which had been reported to have a decay energy of 220 keV. Perey noticed decay particles with an energy level below 80 keV. Perey thought this decay activity might have been caused by a previously unidentified decay product, one which was separated during purification, but emerged again out of the pure actinium-227. Various tests eliminated the possibility of the unknown element being thorium, radium, lead, bismuth, or thallium. The new product exhibited chemical properties of an alkali metal (such as coprecipitating with caesium salts), which led Perey to believe that it was element 87, caused by the alpha decay of actinium-227.[27] Perey then attempted to determine the proportion of beta decay to alpha decay in actinium-227. Her first test put the alpha branching at 0.6%, a figure which she later revised to 1%.[17]

Perey named the new isotope actinium-K (now referred to as francium-223)[27] and in 1946, she proposed the name catium for her newly discovered element, as she believed it to be the most electropositive cation of the elements. Irène Joliot-Curie, one of Perey's supervisors, opposed the name due to its connotation of cat rather than cation.[27] Perey then suggested francium, after France. This name was officially adopted by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry in 1949,[3] becoming the second element after gallium to be named after France. It was assigned the symbol Fa, but this abbreviation was revised to the current Fr shortly thereafter.[32] Francium was the last element discovered in nature, rather than synthesized, following rhenium in 1925.[27] Further research into francium's structure was carried out by, among others, Sylvain Lieberman and his team at CERN in the 1970s and 1980s.[33]

Occurrence

Natural

223Fr is the result of the alpha decay of 227Ac and can be found in trace amounts in uranium and thorium minerals.[4] In a given sample of uranium, there is estimated to be only one francium atom for every 1 × 1018 uranium atoms.[22] It is also calculated that there is at most 30 g of francium in the Earth's crust at any given time.[34]

Synthesis

Francium can be synthesized in the nuclear reaction:

- 197Au + 18O → 210Fr + 5 n

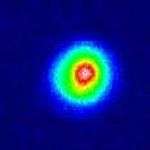

This process, developed by Stony Brook Physics, yields francium isotopes with masses of 209, 210, and 211,[36] which are then isolated by the magneto-optical trap (MOT).[35] The production rate of a particular isotope depends on the energy of the oxygen beam. An 18O beam from the Stony Brook LINAC creates 210Fr in the gold target with the nuclear reaction 197Au + 18O → 210Fr + 5n. The production required some time to develop and understand. It was critical to operate the gold target very close to its melting point and to make sure that its surface was very clean. The nuclear reaction embeds the francium atoms deep in the gold target, and they must be removed efficiently. The atoms quickly diffuse to the surface of the gold target and are released as ions, but this does not happen every time. The francium ions are guided by electrostatic lenses until they land in a surface of hot yttrium and become neutral again. The francium is then injected into a glass bulb. A magnetic field and laser beams cool and confine the atoms. Although the atoms remain in the trap for only about 20 seconds before escaping (or decaying), a steady stream of fresh atoms replaces those lost, keeping the number of trapped atoms roughly constant for minutes or longer. Initially, about 1000 francium atoms were trapped in the experiment. This was gradually improved and the setup is capable of trapping over 300,000 neutral atoms of francium a time.[2] These are neutral metallic atoms in a gaseous unconsolidated state. Enough francium is trapped that a video camera can capture the light given off by the atoms as they fluoresce. The atoms appear as a glowing sphere about 1 millimeter in diameter. This was the first time that anyone had ever seen francium. The researchers can now make extremely sensitive measurements of the light emitted and absorbed by the trapped atoms, providing the first experimental results on various transitions between atomic energy levels in francium. Initial measurements show very good agreement between experimental values and calculations based on quantum theory. Other synthesis methods include bombarding radium with neutrons, and bombarding thorium with protons, deuterons, or helium ions.[17] Francium has not been synthesized in amounts large enough to weigh.[3][7][22]

Footnotes

- ↑ Actually the least unstable isotope, francium-223

- ↑ Some synthetic elements, like technetium and plutonium, have later been found in nature.

References

- ↑ ISOLDE Collaboration, J. Phys. B 23, 3511 (1990) (PDF online)

- 1 2 Luis A. Orozco (2003). "Francium". Chemical and Engineering News.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Price, Andy (December 20, 2004). "Francium". Retrieved February 19, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics 4. CRC. 2006. p. 12. ISBN 0-8493-0474-1.

- ↑ Winter, Mark. "Electron Configuration". Francium. The University of Sheffield. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ↑ Kozhitov, L. V.; Kol'tsov, V. B.; Kol'tsov, A. V. (2003). "Evaluation of the Surface Tension of Liquid Francium". Inorganic Materials 39 (11): 1138–1141. doi:10.1023/A:1027389223381.

- 1 2 "Francium". Los Alamos National Laboratory. 2011. Retrieved February 19, 2012.

- ↑ Pauling, Linus (1960). The Nature of the Chemical Bond (Third ed.). Cornell University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-8014-0333-0.

- ↑ Allred, A. L. (1961). "Electronegativity values from thermochemical data". J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 17 (3–4): 215–221. doi:10.1016/0022-1902(61)80142-5.

- ↑ Andreev, S.V.; Letokhov, V.S.; Mishin, V.I. (1987). "Laser resonance photoionization spectroscopy of Rydberg levels in Fr". Physical Review Letters 59 (12): 1274–76. Bibcode:1987PhRvL..59.1274A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.59.1274. PMID 10035190.

- 1 2 Thayer, John S. (2010). "Relativistic Effects and the Chemistry of the Heavier Main Group Elements": 81. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9975-5_2.

- ↑ Hyde, E. K. (1952). "Radiochemical Methods for the Isolation of Element 87 (Francium)". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 74 (16): 4181–4184. doi:10.1021/ja01136a066.

- ↑ E. N K. Hyde Radiochemistry of Francium,Subcommittee on Radiochemistry, National Academy of Sciences-National Research Council; available from the Office of Technical Services, Dept. of Commerce, 1960.

- ↑ Maddock, A. G. (1951). "Radioactivity of the heavy elements". Q. Rev., Chem. Soc. 3 (3): 270–314. doi:10.1039/QR9510500270.

- ↑ Lide, David R., ed. (2006). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics 11. CRC. pp. 180–181. ISBN 0-8493-0487-3.

- ↑ Considine, Glenn D., ed. (2005). Francium, in Van Nostrand's Encyclopedia of Chemistry. New York: Wiley-Interscience. p. 679. ISBN 0-471-61525-0.

- 1 2 3 "Francium". McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science & Technology 7. McGraw-Hill Professional. 2002. pp. 493–494. ISBN 0-07-913665-6.

- 1 2 3 Considine, Glenn D., ed. (2005). Chemical Elements, in Van Nostrand's Encyclopedia of Chemistry. New York: Wiley-Interscience. p. 332. ISBN 0-471-61525-0.

- ↑ National Nuclear Data Center (1990). "Table of Isotopes decay data". Brookhaven National Laboratory. Retrieved April 4, 2007.

- ↑ National Nuclear Data Center (2003). "Fr Isotopes". Brookhaven National Laboratory. Retrieved April 4, 2007.

- ↑ Winter, Mark. "Uses". Francium. The University of Sheffield. Retrieved March 25, 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Emsley, John (2001). Nature's Building Blocks. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 151–153. ISBN 0-19-850341-5.

- ↑ Gagnon, Steve. "Francium". Jefferson Science Associates, LLC. Retrieved April 1, 2007.

- ↑ Haverlock, TJ; Mirzadeh, S; Moyer, BA (2003). "Selectivity of calix[4]arene-bis(benzocrown-6) in the complexation and transport of francium ion". J Am Chem Soc 125 (5): 1126–7. doi:10.1021/ja0255251. PMID 12553788.

- ↑ Gomez, E; Orozco, L A; Sprouse, G D (November 7, 2005). "Spectroscopy with trapped francium: advances and perspectives for weak interaction studies". Rep. Prog. Phys. 69 (1): 79–118. Bibcode:2006RPPh...69...79G. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/69/1/R02.

- ↑ Peterson, I (May 11, 1996). "Creating, cooling, trapping francium atoms" (PDF). Science News 149 (19): 294. doi:10.2307/3979560. Retrieved September 11, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Adloff, Jean-Pierre; Kaufman, George B. (September 25, 2005). Francium (Atomic Number 87), the Last Discovered Natural Element. The Chemical Educator 10 (5). Retrieved on 2007-03-26.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fontani, Marco (September 10, 2005). "The Twilight of the Naturally-Occurring Elements: Moldavium (Ml), Sequanium (Sq) and Dor (Do)". International Conference on the History of Chemistry. Lisbon. pp. 1–8. Archived from the original on February 24, 2006. Retrieved April 8, 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Van der Krogt, Peter (January 10, 2006). "Francium". Elementymology & Elements Multidict. Retrieved April 8, 2007.

- ↑ "Alabamine & Virginium". TIME. February 15, 1932. Retrieved April 1, 2007.

- ↑ MacPherson, H. G. (1934). "An Investigation of the Magneto-Optic Method of Chemical Analysis". Physical Review (American Physical Society) 47 (4): 310–315. Bibcode:1935PhRv...47..310M. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.47.310.

- ↑ Grant, Julius (1969). "Francium". Hackh's Chemical Dictionary. McGraw-Hill. pp. 279–280. ISBN 0-07-024067-1.

- ↑ "History". Francium. State University of New York at Stony Brook. February 20, 2007. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ↑ Winter, Mark. "Geological information". Francium. The University of Sheffield. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- 1 2 "Cooling and Trapping". Francium. State University of New York at Stony Brook. February 20, 2007. Retrieved May 1, 2007.

- ↑ "Production of Francium". Francium. State University of New York at Stony Brook. February 20, 2007. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

External links

- Francium (Fr) (Chemical element) at Encyclopædia Britannica

- Francium at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)

- WebElements.com – Francium

- Stony Brook University Physics Dept.

| Periodic table (Large cells) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | ||||||||||||||||

| 1 | H | He | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Li | Be | B | C | N | O | F | Ne | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Na | Mg | Al | Si | P | S | Cl | Ar | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | K | Ca | Sc | Ti | V | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Ga | Ge | As | Se | Br | Kr | |||||||||||||||

| 5 | Rb | Sr | Y | Zr | Nb | Mo | Tc | Ru | Rh | Pd | Ag | Cd | In | Sn | Sb | Te | I | Xe | |||||||||||||||

| 6 | Cs | Ba | La | Ce | Pr | Nd | Pm | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | Lu | Hf | Ta | W | Re | Os | Ir | Pt | Au | Hg | Tl | Pb | Bi | Po | At | Rn | |

| 7 | Fr | Ra | Ac | Th | Pa | U | Np | Pu | Am | Cm | Bk | Cf | Es | Fm | Md | No | Lr | Rf | Db | Sg | Bh | Hs | Mt | Ds | Rg | Cn | Uut | Fl | Uup | Lv | Uus | Uuo | |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

|