Fox Chase Rapid Transit Line

| Fox Chase Rapid Transit Line | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Original timetable for the Fox Chase Rapid Transit Line | |||

| Overview | |||

| Type | Rapid transit | ||

| Status | Out of service | ||

| Locale | Pennsylvania | ||

| Termini |

Fox Chase (south) Newtown (north) | ||

| Services | Local | ||

| Operation | |||

| Opened | October 5, 1981 | ||

| Closed | January 14, 1983 | ||

| Owner | SEPTA | ||

| Operator(s) | SEPTA | ||

| Character | Surface | ||

| Technical | |||

| Line length | 15.2 mi (24.5 km)[1] | ||

| No. of tracks | 1 | ||

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) | ||

| Operating speed | 20–40 mph[2] | ||

| |||

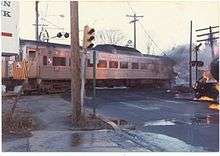

The Fox Chase Rapid Transit line was an experimental transit operation spearheaded by SEPTA from 1981 to 1983, utilizing Philadelphia city transit operators instead of traditional railroad workers. The operation, covering 15.2 miles (24.5 km)[1] between Fox Chase and Newtown, Pennsylvania ended on January 14, 1983, mainly due to the failing train equipment (known as Budd Rail Diesel Cars or "RDC") SEPTA inherited from the bankrupt Reading Company that they had little interest in maintaining or operating.[3] The line is currently known as the dormant section of SEPTA's Fox Chase Line: it is not officially abandoned nor railbanked.[4]

Railroad operations

In 1976 several bankrupt railroads in the Northeast U.S. sold their interests to the newly government-created Conrail.[5] At that time, SEPTA agreed to purchase the Reading Railroad's Newtown, Doylestown and Chestnut Hill branches while Conrail would perform commuter operations.[6] By 1980 Conrail wanted to be relieved of its money-losing commuter rail operations in order to survive financially. The Reagan Administration agreed with Conrail, and granted the operator permission to exit the commuter business on January 1, 1983. Commuter railroad employees and operations became the sole responsibility of local transit agencies.[7] Several newly formed transit agencies were created from this decision, such as the Metro-North Railroad, New Jersey Transit Rail Operations, and MARC. Other regions utilized existing transit agencies to perform the commuter services, such as the MBTA and SEPTA.

City Transit personnel

In anticipation of SEPTA operating all electrified Philadelphia commuter lines by 1983 (as well as already the majority of them), they decided to experiment with operating railroad lines using City Transit Division operators instead of traditional railroad workers as a cost-saving measure. As SEPTA had never run a commuter railroad before (Conrail operated the lines on SEPTA's behalf since 1976),[7] management believed that utilizing transit operators would work just as easily, an opinion shared by City Transit personnel as well.

SEPTA also opted to utilize the City Transit personnel, in part, as a bargaining ploy by which SEPTA was faced with reaching contract agreements with the railroad unions in conjunction with the January 1, 1983, takeover of the electrified commuter trains from Conrail. SEPTA's goal was to prove that, if necessary, it could operate the commuter rail system as a rapid transit operation (like a subway rather than a traditional railroad) and potentially did not need the railroad unions.

Rehabilitation

In July 1981 SEPTA shut down the Fox Chase-Newtown segment of the line, ending direct service to Reading Terminal. SEPTA also terminated its contract with Conrail to operate freight service on the line.[6] Approximately $650,000 ($1,691,856 today) was invested in the line for upgrades and repairs. Rusting grade crossing signals and wayside signals dating from the Reading Company era were repainted and wooden ties and rails were upgraded.[8] In the interim, SEPTA received permission from Pennsylvania Governor Dick Thornburgh to terminate all diesel-hauled commuter services on July 27, 1981, ending service to Reading, Pottsville, Bethlehem and Quakertown.[7] This, in turn, freed up operable RDCs for operations on the Fox Chase-Newtown line.[6]

Start of service

SEPTA initiated operation of the Fox Chase Rapid Transit Line on Monday, October 5, 1981. Branded as Route HS-1,[8] SEPTA chose to utilize TWU Local 234 union employees from the Broad Street Subway. As the subway operators had no experience operating traditional railroad equipment, SEPTA enrolled the union in a six-week training course over the summer to bring the staff up to speed operationally. SEPTA also increased service dramatically along the line. Under Reading Railroad and Conrail auspices, service was minimal, with no more than four round trips between Newtown and Reading Terminal.[9][10] The new transit operation allowed the Fox Chase-Newtown segment eight round trips, the most the line would ever see.[8]

The timetable explained SEPTA's reasoning for operating the line as a transit operation, by saying, "The cost of operating rail diesel service is excessive. In order to preserve the line between Fox Chase and Newtown, SEPTA had to come up with a way to make it affordable. Because the line is now a transit operation—as compared to a commuter railroad line—we are no longer required to pay unneeded employees to run trains with too many cars. Crew sizes and train lengths have been cut in half while the service level has been maintained, and a midday train added. This is a pioneer service."[8]

The initial transition to transit operators did not go smoothly. SEPTA's attempt to eventually operate the entire commuter rail system using TWU employees instead of Conrail union employees met with hostility on the first day of operations. The 6:25 am departure from Newtown never left the station due to Conrail protesters blocking sections of the line. The following 7:43 am departure was delayed 30 minutes, resulting in six protesters being arrested at Fox Chase Station.[6]

The service was unique in several ways:

- it was the only diesel service left operating in the SEPTA system; all other diesel services had been eliminated by July 1981

- it was the only commuter line operated by SEPTA at the time; all other commuter services (all which were electrified) were still operated by Conrail

Incidents

Old Jordan Road

On Monday, December 28, 1981, a single RDC collided with a Northampton Township motorist traveling on Old Jordan Road in Holland driving at high speed. The motorist, who observers reported was playing his radio at high volume, did not hear the train whistle and attempted the cross the tracks despite an approaching train. At this time, the Old Jordan Road crossing was equipped only with crossbucks, and lacked additional hardware (crossings without flashing lights are known in the industry as a "non-controlled" crossing). The motorist was later hospitalized and treated for minor injuries.[11] SEPTA added lights and crossing gates shortly after the accident.[11]

Southampton fire

Five days later, on Saturday, January 2, 1982, another single RDC collided with an ARCO gasoline tanker truck at the Second Street Pike crossing next to Southampton Station.[12] SEPTA motorman Donald Williams was severely burned in the accident and died several days later.[6] The accident caused flames to shoot fifty feet in the air and created a plume of black smoke visible for several miles.[12] Photographs from the fire indicate the crossing signal equipment was working properly, with lights flashing as flames shot into the air.[13]

The Federal Railroad Administration later determined that SEPTA did not follow proper safety standards by running single RDCs that were not intended to operate as single units. Members of Conrail unions who had protested in October 1981 commented that SEPTA was not experienced in operating commuter trains and predicted that an accident would occur. The unions also advised that all but two RDCs had to be run in sets of two in order for the crossing signal equipment to activate properly in anticipation of an oncoming train (Conrail had used four-person crews to operate RDCs). The two RDCs that could operate as one-car trains were car numbers 9151 and 9152, which were specially equipped with "excitation", an electronic device which assured shunting of track circuits when operated as a one-car train.[14] Car number 9164, which was not equipped with "excitation", was involved in the fiery crash and did not activate the crossing circuits at the proper time. The flashing lights did, however, eventually activate by the time the train entered the Second Street Pike crossing.[15] The National Transportation Safety Board determined that the accident was caused by the failure of the RDC to maintain shunt with the track and constantly activate the warning signal. Additionally, the RDC did not have an excitation device that would have allowed it to maintain constant shunt despite a momentary loss of contact. As a result of the accident, the NTSB recommended that SEPTA modify its grade crossing protection systems to ensure that a momentary loss of shunt would not cause warning devices to fail to function. Additionally, the NTSB recommended that SEPTA modify the passenger doors in their RDCs to make them open outward, not inward, to allow passengers easy evacuation in an emergency situation. [16]

When Fox Chase Rapid Transit operations commenced, SEPTA cut the number of cars and operators in half, running all RDCs as single-car units. David Gunn ordered additional safety precautions, and replaced the aged Reading Company railroad crossing warning devices with crossing gates and new flashing lights.[15] As a result of the fire, SEPTA relented and operated the RDCs in groups of two moving forward and had to run shuttle buses in place of trains for approximately one week after the incident.[6]

Operational issues

The Fox Chase Rapid Transit Line had several operational issues when it first began. The 17 RDC units operating on the line were in deplorable condition after years of deferred maintenance courtesy of PennDOT, the Reading Company and Conrail. SEPTA's inexperience with operating a railroad lead to them being reactive to performance problems.As the RDCs failed, motormen were instructed to feed the units excessive amounts of oil, resulting in the destruction of head gaskets on the engines. Since only one set of 2-car RDC units operated on the line at any given time, SEPTA assumed that losing a few derelict surplus units would not greatly hamper service.

In addition, the RDCs also lacked working air conditioning. Motormen often operated the RDCs with the front doors wide open for better air circulation, but the summer of 1982 was a humid one. Sweat-drenched riders opted for the nearby electrified Warminster Line and West Trenton Line, which offered direct service to Reading Terminal in climate controlled cars.

SEPTA was also left without a proper facility to service the ailing RDC units. Originally, trains were serviced at the Reading Company shops at their Reading, Pennsylvania base. With Conrail closing the shops in 1981, SEPTA was left without a maintenance location, resulting in makeshift oil changes being performed at Newtown Station in the presence of passengers.

Changing trains at Fox Chase also caused problems. Conrail motormen were still chafing at SEPTA's choice to operate the Fox Chase-Newtown segment with transit workers. Missed connections at Fox Chase were frequent, as Conrail motormen intentionally departed early when they spotted the RDCs from Newtown approach the station. SEPTA only allowed for a four-minute window for the transfer at Fox Chase, and frustrated riders fled the ailing line.

End of service

Service continued throughout the early winter of 1982. SEPTA began to lose operable RDCs as each set failed. By January 1983, 15 of the 17 RDCs were sidelined due to mechanical problems. Aside from the rush hour, most train service was supplied by a shuttle bus, leading even the most dedicated riders fleeing the line.[6]

Only one round trip between Newtown and Fox Chase was made on January 14, 1983, the final day of service. As the train approached Newtown Station, crew members discovered that a major component of the braking system had become dislodged at Bethayres. The maintenance crew took the last working train out of service and buses were called in to protect the schedule.[6] Without operable RDCs, all service was suspended on a temporary basis.[6]

Since the last train operated in 1983 proposals from both private operators (i.e. Thomas E. Dyer Inc., Rail Easton, Transrail Inc., W.R. Allen, Railroad Construction Co., Railway Management Co. and SEPTA)[6] to restore service have floated throughout the county circles.[3][6] Nearly all proposals have been for resumed train service as a traditional commuter railroad vs. a transit operation.[3][6]

References

- 1 2 Pennypack Creek Watershed Study, p. D3; Temple University, School of Environmental Design

- ↑ Newtown Branch track chart

- 1 2 3 SEPTA's 1991 Newtown Line Reactivation Study

- ↑ abandonedrails.com/Newtown Branch

- ↑ conrail.com/history

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Newtown Branch History.html

- 1 2 3 Woodland, Dale W. (December 2003). "SEPTA's Diesels". Railpace Newsmagazine.

- 1 2 3 4 HS-1 Fox Chase Rapid Transit Line timetable

- ↑ Reading Company 1969 timetable

- ↑ Conrail 1976 timetable

- 1 2 "Train collision causes explosion". Bucks County Courier Times. January 3, 1982.

- 1 2 Halsey, III, Ashley (January 3, 1982). "5 Hurt in Fiery Rail Collision". Philadelphia Inquirer.

- ↑ Stecklow, Steve (January 4, 1982). "Clues Sought in Crash of Train, Truck". Philadelphia Inquirer.

- ↑ Pawson, John R. (1979). Delaware Valley Rails: The Railroads and Rail Transit Lines of the Philadelphia Area. Willow Grove, Pennsylvania: John R. Pawson. pp. 54, 59. ISBN 0-9602080-0-3.

- 1 2 Tulsky, Frederic N. (January 7, 1982). "SEPTA Stiffens Rail Safety Rules". Philadelphia Inquirer.

- ↑ The NTSB's Accident Report

External links

- PA-TEC.org: Fox Chase-Newtown Restoration Proposal

- SEPTA 1991 Newtown Branch Restoration Study (complete)

- The Blue Comet – photos of Newtown Branch prior to 1976

- Newtown Branch and Proposals on Google Maps

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||