Forward osmosis

Forward osmosis (FO) is an osmotic process that, like reverse osmosis (RO), uses a semi-permeable membrane to effect separation of water from dissolved solutes. The driving force for this separation is an osmotic pressure gradient, such that a "draw" solution of high concentration (relative to that of the feed solution), is used to induce a net flow of water through the membrane into the draw solution, thus effectively separating the feed water from its solutes. In contrast, the reverse osmosis process uses hydraulic pressure as the driving force for separation, which serves to counteract the osmotic pressure gradient that would otherwise favor water flux from the permeate to the feed. Hence significantly more energy is required for reverse osmosis compared to forward osmosis.

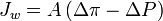

The simplest equation describing the relationship between osmotic and hydraulic pressures and water (solvent) flux is:

where  is water flux, A is the hydraulic permeability of the membrane, Δπ is the difference in osmotic pressures on the two sides of the membrane, and ΔP is the difference in hydrostatic pressure (negative values of

is water flux, A is the hydraulic permeability of the membrane, Δπ is the difference in osmotic pressures on the two sides of the membrane, and ΔP is the difference in hydrostatic pressure (negative values of  indicating reverse osmotic flow). The modeling of these relationships is in practice more complex than this equation indicates, with flux depending on the membrane, feed, and draw solution characteristics, as well as the fluid dynamics within the process itself.[1]

indicating reverse osmotic flow). The modeling of these relationships is in practice more complex than this equation indicates, with flux depending on the membrane, feed, and draw solution characteristics, as well as the fluid dynamics within the process itself.[1]

The solute flux ( ) for each individual solute can be modelled by Fick’s Law

) for each individual solute can be modelled by Fick’s Law

Where  is the solute permeability coefficient and

is the solute permeability coefficient and  is the trans-membrane concentration differential for the solute. It is clear from this governing equation that a solute will diffuse from an area of high concentration to an area of low concentration. This is well known in reverse osmosis where solutes from the feedwater diffuse to the product water, however in the case of forward osmosis the situation can be far more complicated.

is the trans-membrane concentration differential for the solute. It is clear from this governing equation that a solute will diffuse from an area of high concentration to an area of low concentration. This is well known in reverse osmosis where solutes from the feedwater diffuse to the product water, however in the case of forward osmosis the situation can be far more complicated.

In FO processes we may have solute diffusion in both directions depending on the composition of the draw solution and the feed water. This does two things; the draw solution solutes may diffuse to the feed solution and the feed solution solutes may diffuse to the draw solution. Clearly this phenomena has consequences in terms of the selection of the draw solution for any particular FO process. For instance the loss of draw solution may have an impact on the feed solution perhaps due to environmental issues or contamination of the feed stream, such as in osmotic membrane bioreactors.

An additional distinction between the reverse osmosis (RO) and forward osmosis (FO) processes is that the permeate water resulting from an RO process is in most cases fresh water ready for use. In the FO process, this is not the case. The membrane separation of the FO process in effect results in a "trade" between the solutes of the feed solution and the draw solution. Depending on the concentration of solutes in the feed (which dictates the necessary concentration of solutes in the draw) and the intended use of the product of the FO process, this step may be all that is required.

The forward osmosis process is also known as osmosis or in the case of a number of companies who have coined their own terminology 'engineered osmosis' and 'manipulated osmosis'.

Applications

Emergency drinks

One example of an application of this type may be found in "hydration bags", which use an ingestible draw solute and are intended for separation of water from dilute feeds. This allows, for example, the ingestion of water from surface waters (streams, ponds, puddles, etc.) that may be expected to contain pathogens or toxins that are readily rejected by the FO membrane. With sufficient contact time, such water will permeate the membrane bag into the draw solution, leaving the undesirable feed constituents behind. The diluted draw solution may then be ingested directly. Typically, the draw solutes are sugars such as glucose or fructose, which provide the additional benefit of nutrition to the user of the FO device. A point of additional interest with such bags is that they may be readily used to recycle urine, greatly extending the ability of a backpacker or soldier to survive in arid environments.[2] This process may also, in principle, be employed with highly concentrated saline feedwater sources such as seawater, as one of the first intended uses of FO with ingestible solutes was for survival in life rafts at sea.[3]

Desalination

Desalinated water can be produced from the diluted draw / osmotic agent solution, using a second process. This may be by membrane separation, thermal method, physical separation or a combination of these processes. The process has the feature of inherently low fouling because of the forward osmosis first step, unlike conventional reverse osmosis desalination plants where fouling is often a problem. Modern Water has deployed forward osmosis based desalination plants in Gibraltar and Oman.[4][5][6] In March 2010, National Geographic[7] magazine cited forward osmosis as one of three technologies that promised to reduce the energy requirements of desalination.

Evaporative cooling tower – make-up water

One other application developed, where only the forward osmosis step is used, is in evaporative cooling make-up water. In this case the cooling water is the draw solution and the water lost by evaporation is simply replaced using water produced by forward osmosis from a suitable source, such as seawater, brackish water, treated sewage effluent or industrial waste water. Thus in comparison with other ‘desalination’ processes that may be used for make-up water the energy consumption is a fraction of these with the added advantage of the low fouling propensity of a forward osmosis process.[8][9][10]

Landfill leachate treatment

In the case where the desired product is fresh water which does not contain draw solutes, a second separation step is required. The first separation step of FO, driven by an osmotic pressure gradient, does not require a significant energy input (only unpressurized stirring or pumping of the solutions involved). The second separation step, however does typically require energy input. One method used for the second separation step is to employ RO. This approach has been used, for instance, in the treatment of landfill leachate. An FO membrane separation is used to draw water from the leachate feed into a saline (NaCl) brine. The diluted brine is then passed through a RO process to produce fresh water and a reusable brine concentrate. The advantage of this method is not a savings in energy, but rather in the fact that the FO process is more resistant to fouling from the leachate feed than a RO process alone would be.[11] A similar FO/RO hybrid has been used for the concentration of food products, such as fruit juice.[12]

Brine concentration

Brine concentration using forward osmosis may be achieved using a high osmotic pressure draw solution with a means to recover and regenerate it. One such process uses the ammonia-carbon dioxide forward osmosis process originally developed at Yale University[13][14] and commercialized by Oasys Water. Because ammonia and carbon dioxide readily dissociate into gases using heat, the draw solutes can effectively be recovered and reused in a closed loop system. Brine concentration is currently being used in the oil and gas industry to treat produced water in the Permian Basin area of Texas.[15]

Feed water 'softening' / pre-treatment for thermal desalination

One unexploited application[16] is to 'soften' or pre-treat the feedwater to multi stage flash (MSF) or multiple effect distillation (MED) plants by osmotically diluting the recirculating brine with the cooling water. This reduces the concentrations of scale forming calcium carbonate and calcium sulphate compared to the normal process, thus allowing an increase in top brine temperature (TBT), output and gained output ratio (GOR). Darwish et al.[17] showed that the TBT could be raised from 110°C to 135°C whilst maintaining the same scaling index for calcium sulphate.

Osmotic power

In 1954 Pattle[18] suggested that there was an untapped source of power when a river mixes with the sea, in terms of the lost osmotic pressure, however it was not until the mid ‘70s where a practical method of exploiting it using selectively permeable membranes by Loeb [19] and independently by Jellinek[20] was outlined. This process was referred by Loeb as pressure retarded osmosis (PRO) and one simplistic implementation is shown opposite. Some situations that may be envisaged to exploit it are using the differential osmotic pressure between a low brackish river flowing into the sea, or brine and seawater. The worldwide theoretical potential for osmotic power has been estimated at 1,650 TWh / year.[21]

In more recent times a significant amount of research and development work has been undertaken and funded by Statkraft, the Norwegian state energy company. A prototype plant was built in Norway generating a gross output between 2 – 4 kW.[22] A much larger plant with an output of 1 – 2 MW at Sunndalsøra, 400 km north of Oslo was considered[23] but was subsequently dropped.[24] The New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organisation (NEDO) in Japan is funding work on osmotic power.[25]

Research

An area of current research in FO involves direct removal of draw solutes, in this case by means of a magnetic field. Small (nanoscale) magnetic particles are suspended in solution creating osmotic pressures sufficient for the separation of water from a dilute feed. Once the draw solution containing these particles has been diluted by the FO water flux, they may be separated from that solution by use of a magnet (either against the side of a hydration bag, or around a pipe in-line in a steady state process).

References

- ↑ Lee, K (1981). "Membranes for power-generation by pressure-retarded osmosis". Journal of Membrane Science 8 (2): 141–171. doi:10.1016/S0376-7388(00)82088-8.

- ↑ Salter, R.J. (2005). "Forward Osmosis" (PDF). Water Conditioning and Purification 48 (4): 36–38.

- ↑ Kessler, J.O.; Moody, C.D. (1976). "Drinking water from sea water by forward osmosis". Desalination 18 (3): 297–306. doi:10.1016/S0011-9164(00)84119-3.

- ↑ "FO plant completes 1-year of operation" (PDF). Water Desalination Report: 2–3. 15 Nov 2010. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ↑ "Modern Water taps demand in Middle East". The Independent. 23 Nov 2009.

- ↑ Thompson N.A., Nicoll P.G. (September 2011). Forward Osmosis Desalination: A Commercial Reality (PDF). International Desalination Association.

- ↑ "The Big Idea". National Geographic. March 2010. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ↑ P. Nicoll Manipulated Osmosis – an alternative to Reverse Osmosis? Climate Control Middle East, April 2011, 46–49

- ↑ Nicoll P.G., Thompson N.A., Bedford M.R. (September 2011). Manipulated Osmosis Applied To Evaporative Cooling Make-Up Water – Revolutionary Technology (PDF). International Desalination Association.

- ↑ Peter Nicoll, Neil Thompson, Victoria Gray (February 2012). Forward Osmosis Applied to Evaporative Cooling Make-up Water (PDF). Cooling Technology Institute.

- ↑ R. J. York, R. S. Thiel and E. G. Beaudry, Full-scale experience of direct osmosis concentration applied to leachate management, Sardinia ’99 Seventh International Waste Management and Landfill Symposium, S. Margherita di Pula, Cagliari, Sardinia, Italy, 1999.

- ↑ E. G. Beaudry and K. A. Lampi (1990). "Membrane technology for direct osmosis concentration of fruit juices". Food Technology 44: 121.

- ↑ McCutcheon, Jeffrey R.; McGinnis, Robert L.; Elimelech, Menachem (2005). "A novel ammonia—carbon dioxide forward (direct) osmosis desalination process" (PDF). Desalination 174: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2004.11.002.

- ↑ US patent 7560029, Robert McGinnis, "Osmotic Desalination Process", issued 2009-07-14

- ↑ Water Desalination Report, "FO process concentrates oilfield brine". Published October 8, 2012

- ↑ EP patent 2493815, Peter Nicoll, "Thermal Desalination", issued 2013-09-25

- ↑ Mohammed Darwish; Ashraf Hassan; Abdel Nasser Mabrouk; Hassan Abdulrahim; Adel Sharif (10 July 2015). "Viability of integrating forward osmosis (FO) as pretreatment for existing desalting plant". Desalination and Water Treatment. doi:10.1080/19443994.2015.1066270.

- ↑ R.E. Pattle (2 October 1954). "Production of electric power by mixing fresh and salt water in the hydroelectric pile". Nature 174 (4431): 660. doi:10.1038/174660a0.

- ↑ S. Loeb (22 August 1975). "Osmotic power plants". Science 189 (4203): 654–655. doi:10.1126/science.189.4203.654. PMID 17838753.

- ↑ H.H.G. Jellinek (1975). "Osmotic work I. Energy production from osmosis on fresh water/saline water systems". Kagaku Kojo 19.

- ↑ O.S. Scramesto; S.-E. Skillhagen and W.K. Nielsen (27–30 July 2009). "Power production based upon osmotic pressure" (PDF). Waterpower XVI. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ "Tofte prototype plant".

- ↑ "Statkraft considering osmotic power pilot facility at Sunndalsøra". Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ↑ "Statkraft halts osmotic power investments". Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ↑ "Focus on Forward Osmosis, Part 2". Water Desalination Report 49 (15). 22 April 2013.

Further reading

- Cath, T; Childress, A; Elimelech, M (2006). "Forward osmosis: Principles, applications, and recent developments" (PDF). Journal of Membrane Science 281: 70–87. doi:10.1016/j.memsci.2006.05.048.

- Duranceau, Steven (July 2012). "Emergence of Forward Osmosis and Pressure-Retarded Osmotic Processes for Drinking Water Treatment" (PDF). Florida Water Resources Journal: 32–36. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- Nicoll, Peter G. "Forward Osmosis - A Brief Introduction" (PDF). http://idadesal.org/publications/invited-white-papers/. International Desalination Association. Retrieved 13 November 2014. External link in

|website=(help)