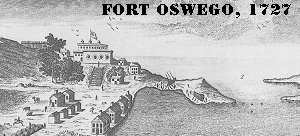

Fort Oswego

Fort Oswego was an important frontier post for French traders in the 18th century. A trading post was established in 1722 with a log palisade, and New York governor William Burnet ordered a fort built at the site in 1727. The log palisade fort established a British presence on the Great Lakes. During the French and Indian War, this fort was captured and destroyed by the French in 1756. The site is now included in the city of Oswego, New York.

Oswego fortification system

Many historic references to Fort Oswego actually refer to other forts that existed simultaneously or later. The terrain at the site explains this. The original fort was built around the trading post on the lower ground on the north west side of the mouth of the Oswego River. This was convenient to canoe and bateaux traffic. A stone blockhouse was added in 1727, and was called Fort Burnet. A triangular stone wall, ten feet (3 m) high and three feet (1 m) wide was added in 1741, and the entire enclosure was called Fort Pepperrell (a marker can be found designating the area of Fort Oswego on the north west side of the river along a sidewalk). Besides these expansions, Fort Ontario was started in 1755 as a palisade on the high ground on the north east side of the river, and Fort George was added to the bluff located a half mile (800 m) to the southwest from Fort Oswego. Fort George was also called Fort Rascal or the West Fort. Fort Ontario was also known as the Fort of the Six Nations or the East Fort. The French knew Fort Oswego as Fort Chouaguen. Some references to Fort Oswego refer to the entire complex. Except for the marker in Oswego, nothing is left of Fort Oswego itself.

Fort Ontario has been rebuilt several times on or around the original fort and was given up by the U.S. Army in the 1940s. The fort is currently being taken care of by New York State Parks and Historic Preservation and is opened to the public.

The French and Indian War

During the French and Indian War, the French commander, General Montcalm, arrived in August with 3,000 men. His force included 3 regiments of regulars, several companies of Canadian militia, and numerous Indians. He first captured Fort Ontario, then began the assault on Fort Oswego. Oswego was the stronger fortification, but it was now downhill from 120 cannons in the abandoned Fort Ontario. Montcalm swept the fort with cannon fire, killing the British commander, Colonel Mercer, in the bombardment. British forces were forced to surrender on August 15, 1756.

Montcalm gave much of the British supplies to his Indian allies, and destroyed the fort. He returned to Quebec in triumph with 1,700 prisoners. His actions made a strong impression on the Indian allies of the British, and caused the Oneida and the Seneca tribes to switch to the French side.

Later actions

%2C_War_of_1812.jpg)

The site was used for shore batteries in the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 (when it was subjected to a British raid), but was never again fortified. Revolutionary War references to Fort Oswego are actually referring to Fort Ontario. The original site is commemorated at West First and Lake Street in Oswego, New York. Fort George was located in what is now Montcalm Park. Fort Ontario was maintained irregularly throughout the 19th and 20th centuries as a military base and is currently open as a state historic site.

Michael Keane

An interesting anecdote about Fort Oswego in the 1750s states: "I knew a Michael Keane, a blind harper, who was born in the County Mayo in Connaught. He was a decent performer. He left this country for America with a Governor Dobbs, of Castle Dobbs, in the County of Antrim, who was appointed to the Government of Carolina, previous to the American Independence. Keane returned from America, and Sir Malby Crofton told this story of Keane, that when he and some other officers were garrisoned at Fort Oswego, and had a party, Keane was with them, and quarrelled with them, and beat them very well, and took a Miss Williams from them all. He left the Governor, and came back to his native country which he longed to see." [1]

References

- ↑ "Memoirs of Arthur O'Neill" in Fox, Charlotte Milligan (1911). Annals of the Irish Harpers. London: Smith Elder & Co. p. 169.

- Graymont, Barbara, The Iroquois in the American Revolution, 1972, ISBN 0-8156-0083-6

External links

Coordinates: 43°27′42″N 76°30′51″W / 43.46167°N 76.51417°W