New Sweden

| New Sweden | |||||

| Nya Sverige | |||||

| Swedish colony | |||||

| |||||

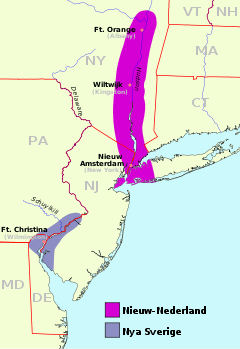

Map of New Sweden ca. 1650 by Amandus Johnson | |||||

| Capital | Fort Christina | ||||

| Languages | Swedish, Finnish | ||||

| Political structure | Colony | ||||

| King/Queen of Sweden | |||||

| • | 1632–1654 | Christina | |||

| • | 1654–1660 | Charles X Gustav | |||

| Governor | |||||

| • | 1638 | Peter Minuit | |||

| • | 1638–1640 | Måns Nilsson Kling | |||

| • | 1640–1643 | Peter Hollander Ridder | |||

| • | 1643–1653 | Johan Björnsson Printz | |||

| • | 1653–1654 | Johan Papegoja | |||

| • | 1654–1655 | Johan Risingh | |||

| Historical era | Colonial period | ||||

| • | Established | 1638 | |||

| • | Dutch conquest | 1655 | |||

| • | Peach Tree War | 1655 | |||

| Currency | Swedish riksdaler | ||||

| Today part of | | ||||

New Sweden (Swedish: Nya Sverige, Finnish: Uusi Ruotsi, Latin: Nova Svecia) was a Swedish colony along the lower reaches of Delaware River in North America from 1638 to 1655[1] in the present-day American Mid-Atlantic states of Delaware, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. Fort Christina, now in Wilmington, Delaware, was the first settlement. Along with Swedes and Finns, a number of the settlers were Dutch. New Sweden was conquered by the Dutch in 1655, during the Second Northern War, and incorporated into New Netherland.

History

By the middle of the 17th century the Realm of Sweden had reached its greatest territorial extent and was one of the great powers of Europe. Sweden then included Finland and Estonia along with parts of modern Russia, Poland, Germany and Latvia, under King Gustavus Adolphus and later Christina, Queen of Sweden. The Swedes sought to expand their influence by creating an agricultural (tobacco) and fur-trading colony to bypass French and English merchants.

The Swedish West India Company began with a mandate to establish colonies between Florida and Newfoundland for the purposes of trade, particularly concentrated in the Delaware River. Its charter included Swedish, Dutch, and German stockholders led by directors of the New Sweden Company, including Samuel Blommaert.[2] The Company sponsored 11 expeditions made up of 14 separate voyages (two did not survive) to Delaware between 1638 and 1655.

The first Swedish expedition to North America embarked from the port of Gothenburg in late 1637. It was organized and overseen by Clas Fleming, a Swedish Admiral from Finland. A Dutchman, Samuel Blommaert, assisted the fitting-out and appointed Peter Minuit (the former Governor of New Amsterdam) to lead the expedition. The members of the expedition, aboard the ships Fogel Grip and Kalmar Nyckel, sailed into Delaware Bay, which lay within the territory claimed by the Dutch, passing Cape May and Cape Henlopen in late March 1638,[3] and anchored at a rocky point on the Minquas Kill that is known today as Swedes' Landing on March 29, 1638. They built a fort on the present site of the city of Wilmington, which they named Fort Christina, after Queen Christina of Sweden.[4]

In the following years, 600 Swedes and Finns, the latter group mainly Forest Finns from central Sweden, and also a number of Dutchmen and Germans in Swedish service, settled in the area. Peter Minuit was to become the first governor of the newly established colony of New Sweden. Having been the Director of the Dutch West India Company, and the predecessor of then-Director William Kieft, Minuit knew the status of the lands on either side of the Delaware River at that time. He knew that the Dutch had established deeds for the lands east of the river (New Jersey), but not for the lands to the west (Maryland, Delaware, and Pennsylvania).

Minuit made good on his appointment by landing on the west bank of the river and gathered the sachems of the local Delaware tribe. Sachems of the Susquehannocks were also present. They held a conclave in his cabin on the Kalmar Nyckel, and he persuaded the sachems to sign deeds he had prepared for the purpose to solve any issue with the Dutch. The Swedes claimed the section of land purchased included the land on the west side of the South River from just below the Schuylkill, in other words, today's Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, southeastern Pennsylvania, Delaware, and coastal Maryland. The Delaware sachem Mattahoon, who was one of the participants, later stated that only as much land as was contained within an area marked by "six trees" was purchased and that the rest of the land occupied by the Swedes was stolen.[5]

Director Willem Kieft objected to the landing of the Swedes, but Minuit ignored him, since he knew that the Dutch were militarily impotent at the moment. Minuit finished Fort Christina during 1638, then departed for Stockholm for a second group. He made a side trip to the Caribbean to pick up a shipment of tobacco for resale in Europe to make the voyage profitable. Minuit died on this voyage during a hurricane at St. Christopher in the Caribbean.

The official duties of the first governor of New Sweden were carried out by Lieutenant (promoted to Captain) Måns Nilsson Kling, until a new governor was chosen and brought from Sweden two years later.[6]

Under Johan Björnsson Printz, governor from 1643 to 1653, the company expanded along the river from Fort Christina, establishing Fort Nya Elfsborg on the east bank of the Delaware near present-day Salem, New Jersey and Fort Nya Gothenborg on Tinicum Island (to the immediate southwest of today's Philadelphia), where he also built his manor house, The Printzhof. The Swedish colony prospered at first. In 1644, New Sweden supported the Susquehannocks in their victory in a war against the English in the Province of Maryland.[7] In May 1654, the Dutch Fort Casimir was captured by soldiers from the New Sweden colony led by governor Johan Risingh. Fort Casimir was renamed Fort Trinity (in Swedish, Trefaldigheten).

Soon after Sweden opened the Second Northern War in the Baltic by attacking the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Dutch moved to take advantage and an armed squadron of ships under the direction of Director-General Peter Stuyvesant seized New Sweden. The Dutch moved an army to the Delaware River in the summer of 1655, easily capturing Fort Trinity and Fort Christina. The Swedish settlement was incorporated into Dutch New Netherland on September 15, 1655. At first the Swedish and Finnish settlers continued to enjoy local autonomy. They kept their own militia, religion, court, and lands.[8]

This status lasted officially until the English conquest of the New Netherland colony was launched on June 24, 1664. The Duke of York sold the area that is today New Jersey to John Berkeley and George Carteret for a proprietary colony, separate from the projected New York. The actual invasion started on August 29, 1664, with the capture of New Amsterdam. The invasion ended with the capture of Fort Casimir (New Castle, Delaware) in October 1664. The invasion was conducted at the start of the Second Anglo-Dutch War.[9]

The status continued unofficially until these lands were included in William Penn's charter for Pennsylvania, on August 24, 1682. During this later period some immigration and expansion continued. The first settlement at Wicaco, a Swedish settlers' log blockhouse located below Society Hill, was built in present-day Philadelphia in 1669. It was later used as a church until about 1700, when Gloria Dei (Old Swedes') Church of Philadelphia was built on the site.[10]

Hoarkill, New Amstel, and Upland

The start of the Third Anglo-Dutch War resulted in the recapture of New Netherland by the Dutch in August 1673. The Dutch restored the status that pre-dated the English invasion, and codified it in the establishment of three counties in what had been New Sweden. They were Hoarkill County, which today is Sussex County, Delaware;[11] New Amstel County, which is today New Castle County, Delaware;[11] and Upland County, which was later partitioned between New Castle County, Delaware and the new Colony of Pennsylvania.[11] The three counties were created on September 12, 1673, the first two on the west shore of the Delaware River, and the third on both sides of the river.

The signing of the Treaty of Westminster of 1674 ended the Dutch effort, and required them to return all of New Netherland to the English, including the three counties they created. That handover took place on June 29, 1674.[12]

After taking stock, the English declared on November 11, 1674, that settlements on the west side of the Delaware River and Delaware Bay (in present-day Delaware and Pennsylvania) were to be dependent on the Colony of New York, including the three Counties.[13] This declaration was followed on November 11 by a new declaration that renamed New Amstel as New Castle. The other counties retained their Dutch names for the duration.[13]

The next step in the assimilation of New Sweden into New York was the extension of the Duke's laws into the region. This took place on September 22, 1676.[14] This was followed by the partitioning of the Counties to conform to the borders of Pennsylvania and Delaware.

The first move was to partition Upland between Delaware and Pennsylvania, with most of the Delaware portion going to New Castle County. This was accomplished on November 12, 1678.[15] The remainder of Upland continued in place under the same name.

On June 21, 1680, New Castle and Hoarkill Counties were partitioned to produce St. Jones County.[16]

On March 4, 1681, what had been the colony of New Sweden was formally partitioned into the colonies of Delaware and Pennsylvania. The border was established 12 miles north of New Castle, and the northern limit of Pennsylvania was set at 42 degrees north latitude. The eastern limit was the current border with New Jersey at the Delaware River, while the western limit was undefined.[17] Pennsylvania immediately started to reorganize the lands of the former New Sweden within the limits of Pennsylvania. In June 1681, Upland ceased to exist as the result of the reorganization of the Colony of Pennsylvania, with the Upland government becoming the government of Chester County, Pennsylvania.

On August 24, 1682, the Duke of York transferred the western Delaware River region, including modern-day Delaware, to William Penn, thus transferring Deale and St. Jones from New York to Delaware. St. Jones County was renamed as Kent County; Deale County was renamed Sussex County; New Castle County retained its name.[18]

Significance and legacy

The historian H. Arnold Barton has suggested that the greatest significance of New Sweden was the strong and long-lasting interest in North America that the colony generated in Sweden.[19] Major Swedish immigration to the United States did not occur until the late 19th century, however. From 1870 to 1910, over one million Swedes arrived, settling particularly in Minnesota and other states of the Upper Midwest (see Swedish American).

Traces of New Sweden persist in the lower Delaware Valley to this day, including Holy Trinity Church in Wilmington, Gloria Dei Church and St. James Kingsessing Church in Philadelphia, Trinity Episcopal Church in Swedesboro, New Jersey, and Christ Church (est. 1760) in Swedesburg, Pennsylvania, all commonly known as "Old Swedes' Church".[20] Christiana, Delaware, is one of the few settlements in the area with a Swedish name. Swedesford Road is still found in Chester and Montgomery Counties, Pennsylvania, although Swedesford has long since become Norristown. The American Swedish Historical Museum, located in FDR Park in South Philadelphia, houses many exhibits, documents and artifacts from the New Sweden colony.

Perhaps the greatest contribution of New Sweden to the development of the New World is one that is the traditional Finnish forest house building technique. The colonists brought with them the log cabin, which became such an icon of the American frontier that it is thought of as an American structure.[21] The C. A. Nothnagle Log House on Swedesboro-Paulsboro Road in Gibbstown, New Jersey, is one of the oldest surviving log houses in the United States.[22][23]

Finnish influence

The colonists came from all over the Swedish realm. The percentage of Finns in New Sweden grew especially towards the end of the colonization,[24] comprising 22% of the population during Swedish rule, but rising to about 50% after the colony came under Dutch rule.[25] The year 1664 saw the arrival of a contingent of 140 Finns. In 1655, when the ship Mercurius sailed to the colony, 92 of the 106 passengers were listed as Finns. Memory of the early Finnish settlement lived on in place names near the Delaware River such as Finland (Marcus Hook), Torne, Lapland, Finns Point and Mullica Hill and Mullica River.[26]

A portion of these Finns were known as Forest Finns, people of Finnish descent living in the forest areas of Central Sweden. The Forest Finns had moved from Savonia in Eastern Finland to Dalarna, Bergslagen and other provinces in central Sweden during the late-16th and early-to-mid-17th centuries. Their relocation had started as part of an effort by Swedish king Gustav Vasa, to expand agriculture to these uninhabited parts of the country. The Finns in Savonia traditionally farmed with a slash-and-burn method which was better suited to pioneering agriculture in vast forest areas. This was also the farming method used by the Native Americans of Delaware.[27]

Forts

- Fort Christina (1638) – located at the confluence of the Brandywine Creek and the Christina River in Wilmington, Delaware.

- Fort Mecoponacka (1641) – located in Chester as a defense for the settlement then known as Finlandia, near Upland, Delaware County, Pennsylvania.

- Fort Nya Elfsborg (1643) – located on the New Jersey side of the Delaware River, between present day Salem River and Alloway Creek outside Salem in Elsinboro Township, New Jersey

- Fort Nya Gothenborg (1643) – located on Tinicum Island near the site of The Printzhof in Essington, Pennsylvania.

- Fort Nya Vasa (1646) – located at Kingsessing, on the eastern side of Cobbs Creek near Cobbs Creek Parkway and Greenway Avenue in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

- Fort Nya Korsholm (1647) – located at the mouth of the Schuylkill River, probably on Province Island, near the western approach of the Penrose Avenue Bridge in Philadelphia.

- Fort Casimir (1654) – also known as Fort Trinity (in Swedish, Trefaldigheten), located at the end of Chestnut Street near Harmony & 2nd streets in New Castle, Delaware.

Permanent settlements

- Christina (1638 & 1641; modern Wilmington, Del.)[28]

- Finland, Finlandia, or Chamassungh (1641 & 1643; modern Marcus Hook, Penn.)[28]

- Upland or Uppland (1641 & 1643; modern Chester, Penn.)[28]

- Varkens Kill (1641); modern Salem County, New Jersey[29][30][31]

- Printztorp (1643; modern Chester, Penn.)[28]

- Tequirassy (1643; modern Eddystone, Penn.)[28]

- Tenakonk or Tinicum (1643; modern Tinicum, Penn.)[28]

- Provins, Druweeÿland, or Manaiping[28] (1643; modern southwest Philadelphia, Penn., on Province Island on the Schuylkill River)

- Minquas or Minqua's Island (1644; modern southwest Philadelphia, Penn.)[28]

- Kingsessing (1644; modern southwest Philadelphia, Penn.)[28]

- Mölndal (1645; modern Yeadon, Penn.)[28]

- Torne (1647; modern West Philadelphia, Penn.)[28]

- Sveaborg[32][33] (c. 1649; modern Swedesboro, N.J.)

- Nya Stockholm (c. 1649; modern Bridgeport, N.J.)

- Sidoland (1654; modern Wilmington, Del.)[28]

- Översidolandet (1654; modern Wilmington, Del.)[28]

- Timmerön or Timber Island (1654; modern Wilmington, Del.)[28]

- Strandviken (1654; modern Wilmington, Del.)[28]

- Ammansland (1654; modern Darby, Penn.)[28]

Rivers and creeks

- Delaware River: "South River" (Södre Rivier; as opposed to the Hudson), "Swedish River" (Swenskes Rivier), "New Sweden River" (Nya Sweriges Rivier)[28]

- Schuylkill River: "Schuyl Creek" (Schuylen Kÿl)[28] meaning hidden river

- Brandywine Creek: "Fish Creek" (Fiske Kÿl)

- Christina River: "Susquehanna" (Minquas) or "Christina Creek" (Christina Kÿl)

- Raccoon Creek: "Narraticon" (Lenape) meaning Raccoon[34][35]

- Salem River: Varkens Kill (Hogg Creek)

- Mullica River, named for an early Finnish settler, Eric Pålsson Mullica

See also

- C. A. Nothnagle Log House

- Swedish emigration to North America

- European colonization of the Americas

- Possessions of Sweden

- Swedish American

- Upland Court

- Finnish American

- American Swedish Historical Museum

- Rambo apple

- Kalmar Nyckel

- Laurentius Carels, Swedish American Lutheran pastor

- Wedge (border)

- New Sweden Farmstead Museum

- Old Swedes' Church

Footnotes

- ↑ "Delaware". World Statesmen. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- ↑ A Brief History of New Sweden in America (The Swedish Colonial Society)

- ↑ McCormick, p. 12; Munroe, Colonial Delaware, p. 16.

- ↑ Thorne, Kathryn Ford, Compiler, & Long, John H., Editor: New York Atlas of Historical County Boundaries; p. 5; The Newbury Library; 1993.

- ↑ Jennings, p.117

- ↑ Shorto, Russell, The Island at the Center of the World, Part II; Chapter 6; Pages 115–117.

- ↑ Jennings, p. 120

- ↑ Upland Court (West Jersey History Project)

- ↑ Munroe, History of Delaware, pp. 30–31

- ↑ Gloria Dei (Old Swedes') Church(National Park Service)

- 1 2 3 Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York; Vol. 12; pp. 507–508.

- ↑ Parry, Clive, ed. Consolidated Treaty Series.; Vol. 13, p. 136; Dobbs Ferry, New York; Oceana Publications, 1969–1981.

- 1 2 Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York; Vol. 12; Page 515.

- ↑ Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York; Volume 12; pp. 561–563.

- ↑ Armstrong, Edward (1860). Memoirs of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania: Volume 119; Record of the Court at Upland, in Pennsylvania, 1676 to 1681. Pennsylvania: Historical Society of Pennsylvania. p. 198.

- ↑ Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York.; Vol. 12, pp. 654, 664, 666–667.

- ↑ Armstrong, Edward (1860). Memoirs of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania: Volume 119; Record of the Court at Upland, in Pennsylvania, 1676 to 1681. Pennsylvania: Historical Society of Pennsylvania. p. 196.

- ↑ Pennsylvania Archives, 2nd series, Vol. 5: pp. 739–744.

- ↑ Barton, A Folk Divided, 5–7.

- ↑ Project Canterbury. Swedish Folk within Our Church (Thomas Burgess. New York: Foreign-Born Americans Division, Episcopal Diocese of New York. National Council, 1929) http://anglicanhistory.org/lutherania/swedish_folk

- ↑ Mary Trotter Kion, "New Sweden: The First Colony in Delaware". July 23, 2006; accessed 2010.03.10.

- ↑ "Nothnagle Log Cabin, Gibbstown". Art and Archtitecture of New Jersey. Richard Stokton College of New Jersey. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- ↑ OLDEST - Log House in North America - Superlatives on. Waymarking.com. Retrieved on July 23, 2013.

- ↑ The Finns on the Delaware (New Sweden Tercentenary)

- ↑ Wedin, Maud (October 2012). "Highlights of Research in Scandinavia on Forest Finns" (PDF). American-Swedish Organization. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- ↑ Spiegel, Taru. "The Finns in America". European Reading Room. Library of Congress. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- ↑ "Finland monument at Concord Avenue in Chester, Pennsylvania". Historical Markers. ExplorePAhistory.com. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Johnson, Amandus. The Swedish settlements on the Delaware, 1638–1664.. Swedish Colonial Society, 1911.

- ↑ Chandler, Alfred N. (2000) [1945], Land Title Origins: A Tale of Force and Fraud, Beard Books, p. 242, ISBN 1-893122-89-1

- ↑ Sheridan, Janet L. (2007). ""Their houses are some Built of timber": The colonial timber frame houses of Fenwick's Colony, New Jersey". University of Michigan Ann Arbor: 182. Retrieved July 24, 2013.

- ↑ Howe, Henry; Barber, John W. (1844), Salem, NJ, New York: S. Tuttle,

In 1641, some English families, (probably emigrants from New Haven, Conn.,) embracing about 60 persons, settled on Ferken's creek, (now Salem.) About this period, the Swedes bought of the Indians the whole district from Cape May to Raccoon creek; and, in order to unite these English with the Swedes, the Swedish governor, Printz, who arrived from Sweden the year after, (1642,) was to "act kindly and faithfully toward them; and as these English expected soon, by further arrivals, to increase their numbers to several hundreds, and seemed also willing to be subjects of the Swedish government, he was to receive them under allegiance, though not without endeavoring to effect their removal."

- ↑ Williams, Rev. Dr. Kim-Eric. "Trinity Episcopal Church". The Swedish Colonial Society.

- ↑ "History: Early Settlement". Trinity Episcopal "Old Swedes" Church. Trinity Episcopal "Old Swedes" Church.

- ↑ Roncace, Kelly (May 14, 2012). "What's in a Name? Raccoon Creek". South Jersey Times. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- ↑ http://www.nj.com/gloucester/voices/index.ssf/2010/11/the_kepharts_cohawkin_raccoon.html

References

- Barton, H. Arnold (1994). A Folk Divided: Homeland Swedes and Swedish Americans, 1840–1940. (Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis).

- Benson, Adolph B. and Naboth Hedin, eds. Swedes in America, 1638–1938 (The Swedish American Tercentenary Association. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. 1938) ISBN 978-0-8383-0326-9

- Jennings, Francis, (1984) The Ambiguous Iroquois, (New York: Norton) ISBN 0-393-01719-2

- Johnson, Amandus (1927) The Swedes on the Delaware (International Printing Company, Philadelphia)

- Munroe, John A. (1977) Colonial Delaware (Delaware Heritage Press, Wilmington)

- Shorto, Russell (2004) The Island at the Center of the World (Doubleday, New York ) ISBN 0-385-50349-0

- Weslager, C.A. (1990) A Man and his Ship, Peter Minuet and the Kalmar Nyckel (Kalmar Nyckel Foundation, Wilmington ) ISBN 0-9625563-1-9

- Weslager, C. A. (1988) New Sweden on the Delaware 1638–1655 (The Middle Atlantic Press, Wilmington ) ISBN 0-912608-65-X

- Weslager, C. A.(1987) The Swedes and Dutch at New Castle (The Middle Atlantic Press, Wilmington) ISBN 0-912608-50-1

Additional reading

- Mickley, Joseph J. Some Account of William Usselinx and Peter Minuit: Two individuals who were instrumental in establishing the first permanent colony in Delaware (The Historical Society of Delaware. 1881)

- Jameson, J. Franklin Willem Usselinx: Founder of the Dutch and Swedish West India Companies (G.P. Putnam's Sons. 1887)

- Myers, Albert Cook, ed. Narratives of Early Pennsylvania, West New Jersey, and Delaware, 1630–1707. (New York, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1912)

- Ward, Christopher Dutch and Swedes on the Delaware, 1609–1664 (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1930)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to New Sweden. |

- The Finns in American Colonial History

- The American Swedish Historical Museum

- A Brief History of New Sweden in America, at The Swedish Colonial Society

- The New Sweden Centre – museum, tours and reenactors

- New Sweden at the FamilySearch Research Wiki

- Johnson's detailed map of New Sweden

- 350th Anniversary of the Landing of the Swedes and Finns in Delaware

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||

Coordinates: 39°44′13.64″N 75°32′18.46″W / 39.7371222°N 75.5384611°W