Formula for primes

In number theory, a formula for primes is a formula generating the prime numbers, exactly and without exception. No such formula which is efficiently computable is known. A number of constraints are known, showing what such a "formula" can and cannot be.

Prime formulas and polynomial functions

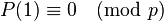

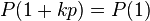

It is known that no non-constant polynomial function P(n) with integer coefficients exists that evaluates to a prime number for all integers n. The proof is as follows: Suppose such a polynomial existed. Then P(1) would evaluate to a prime p, so  . But for any k,

. But for any k,  also, so

also, so  cannot also be prime (as it would be divisible by p) unless it were p itself, but the only way

cannot also be prime (as it would be divisible by p) unless it were p itself, but the only way  for all k is if the polynomial function is constant.

for all k is if the polynomial function is constant.

The same reasoning shows an even stronger result: no non-constant polynomial function P(n) exists that evaluates to a prime number for almost all integers n.

Euler first noticed (in 1772) that the quadratic polynomial

- P(n) = n2 + n + 41

is prime for all natural numbers less than 40. The primes for n = 0, 1, 2, ... are 41, 43, 47, 53, 61, 71... The differences between the terms are 2, 4, 6, 8, 10... For n = 40, it produces a square number, 1681, which is equal to 41×41, the smallest composite number for this formula. If 41 divides n, it divides P(n) too. The phenomenon is related to the Ulam spiral, which is also implicitly quadratic, and the class number;

this polynomial is related to the Heegner number  , and there are analogous polynomials for

, and there are analogous polynomials for  (the lucky numbers of Euler), corresponding to other Heegner numbers.

(the lucky numbers of Euler), corresponding to other Heegner numbers.

It is known, based on Dirichlet's theorem on arithmetic progressions, that linear polynomial functions  produce infinitely many primes as long as a and b are relatively prime (though no such function will assume prime values for all values of n). Moreover, the Green–Tao theorem says that for any k there exists a pair of a and b with the property that

produce infinitely many primes as long as a and b are relatively prime (though no such function will assume prime values for all values of n). Moreover, the Green–Tao theorem says that for any k there exists a pair of a and b with the property that  is prime for any n from 0 to k − 1. However, the best known result of such type is for k = 26 (by Benoãt Perichon of France):

is prime for any n from 0 to k − 1. However, the best known result of such type is for k = 26 (by Benoãt Perichon of France):

- 43142746595714191 + 5283234035979900n is prime for all n from 0 to 25 (Perichon 2010).

It is not even known whether there exists a univariate polynomial of degree at least 2 that assumes an infinite number of values that are prime; see Bunyakovsky conjecture.

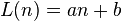

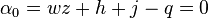

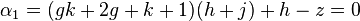

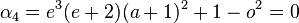

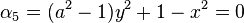

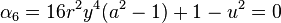

Formula based on a system of Diophantine equations

Because the set of primes is a computably enumerable set, by Matiyasevich's theorem, it can be obtained from a system of Diophantine equations. Jones et al. (1976) found an explicit set of 14 Diophantine equations in 26 variables, such that a given number k + 2 is prime if and only if that system has a solution in natural numbers:

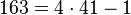

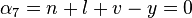

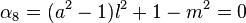

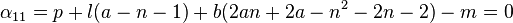

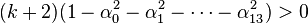

The 14 equations α0, …, α13 can be used to produce a prime-generating polynomial inequality in 26 variables:

i.e.:

is a polynomial inequality in 26 variables, and the set of prime numbers is identical to the set of positive values taken on by the left-hand side as the variables a, b, …, z range over the nonnegative integers.

A general theorem of Matiyasevich says that if a set is defined by a system of Diophantine equations, it can also be defined by a system of Diophantine equations in only 9 variables (Matiyasevich 1999). Hence, there is a prime-generating polynomial as above with only 10 variables. However, its degree is large (in the order of 1045). On the other hand, there also exists such a set of equations of degree only 4, but in 58 variables. See (Jones 1982).

Mills' formula

The first such formula known was established by W. H. Mills (1947), who proved that there exists a real number A such that

is a prime number for all positive integers n. If the Riemann hypothesis is true, then the smallest such A has a value of around 1.3063... and is known as Mills' constant. This formula has no practical value, because very little is known about the constant (not even whether it is rational), and there is no known way of calculating the constant without finding primes in the first place.

Recurrence relation

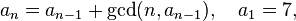

Another prime generator is defined by the recurrence relation

where gcd(x, y) denotes the greatest common divisor of x and y. The sequence of differences an + 1 − an starts with 1, 1, 1, 5, 3, 1, 1, 1, 1, 11, 3, 1, 1, ... (sequence A132199 in OEIS). Rowland (2008) proved that this sequence contains only ones and prime numbers.

See also

References

- Jones, James P.; Sato, Daihachiro; Wada, Hideo; Wiens, Douglas (1976), "Diophantine representation of the set of prime numbers", American Mathematical Monthly (Mathematical Association of America) 83 (6): 449–464, doi:10.2307/2318339, JSTOR 2318339.

- Jones, James P. (1982), "Universal diophantine equation", Journal of Symbolic Logic 47 (3): 549–571, doi:10.2307/2273588.

- Matiyasevich, Yuri V. (1999), "Formulas for Prime Numbers", in Tabachnikov, Serge, Kvant Selecta: Algebra and Analysis, II, American Mathematical Society, pp. 13–24, ISBN 978-0-8218-1915-9.

- Mills, W. H. (1947), "A prime-representing function" (PDF), Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 53 (6): 604, arXiv:1408.1888, doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1947-08849-2.

- Perichon, Benoãt (2010), A World Record AP26 (Arithmetic Progression of 26 primes) (PDF), The AP26 is listed in "Jens Kruse Andersen's Primes in Arithmetic Progression Records page", retrieved 2014-06-25.

- Regimbal, Stephen (1975), "An explicit Formula for the k-th prime number", Mathematics Magazine (Mathematical Association of America) 48 (4): 230–232, doi:10.2307/2690354, JSTOR 2690354.

- Rowland, Eric S. (2008), "A Natural Prime-Generating Recurrence", Journal of Integer Sequences 11: 08.2.8, arXiv:0710.3217, Bibcode:2008JIntS..11...28R.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Prime Formulas", MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Prime-Generating Polynomial", MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Mill's Constant", MathWorld.

- A Venugopalan. Formula for primes, twinprimes, number of primes and number of twinprimes. Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences—Mathematical Sciences, Vol. 92, No 1, September 1983, pp. 49–52. Page 49, 50, 51, 52, errata.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![[wz + h + j - q]^2 -](../I/m/06ff2eac8affaa1ff710f567e9c4f462.png)

![[(gk + 2g + k + 1)(h + j) + h - z]^2 -](../I/m/13bb558fed54cd29a1a4b67499db53c3.png)

![[16(k + 1)^3(k + 2)(n + 1)^2 + 1 - f^2]^2 -](../I/m/e36acf4dfd7c2f75a11e61bca35e8e77.png)

![[2n + p + q + z - e]^2 -](../I/m/5d7214bdc8957edd116e99a882b3b737.png)

![[e^3(e + 2)(a + 1)^2 + 1 - o^2]^2 -](../I/m/c58df1d00436a92c0419b2730ee60c8f.png)

![[(a^2 - 1)y^2 + 1 - x^2]^2 -](../I/m/898b31e40f3e81a0a4603e0994f9bba5.png)

![[16r^2y^4(a^2 - 1) + 1 - u^2]^2 -](../I/m/0c08057084db42978168a03cb53ccc36.png)

![[n + l + v - y]^2 -](../I/m/184097024883708a95ef51f22ed52d4e.png)

![[(a^2 - 1)l^2 + 1 - m^2]^2 -](../I/m/2ec23570d3bd9dfafd257d1e3a677975.png)

![[ai + k + 1 - l - i]^2 -](../I/m/9c3aed8531996461ff57051f23224268.png)

![[((a + u^2(u^2 - a))^2 - 1)(n + 4dy)^2 + 1 - (x + cu)^2]^2 -](../I/m/06a0517b9de1887eb466d7719c01ffc0.png)

![[p + l(a - n - 1) + b(2an + 2a - n^2 - 2n - 2) - m]^2 -](../I/m/cbe6640085dffc8091207de83057f95a.png)

![[q + y(a - p - 1) + s(2ap + 2a - p^2 - 2p - 2) - x]^2 -](../I/m/16479ad03b5905fc081bf5ab1b2dfac3.png)

![[z + pl(a - p) + t(2ap - p^2 - 1) - pm]^2)](../I/m/0b7a73edbd2e5a45a0abdd7084df5fd7.png)