Fokker Scourge

The Fokker Scourge (also sometimes called the Fokker Scare) was a phase of the contest for air superiority on the Western Front during the First World War. During this phase, the synchronised machine-gun armed Fokker Eindecker monoplane fighter aircraft of the Imperial German Fliegertruppen (Flying Corps) held a tactical advantage over poorly armed Allied aircraft, enabling a degree of air superiority.[1] Significant as the technical advantage of the new fighter was, the psychological effect of its unheralded introduction was also a major factor.[2]

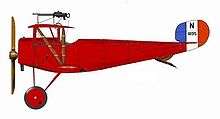

The period is usually considered to have begun in July–August 1915[3] and ended in early 1916, with the arrival in numbers of the Allied Nieuport 11 and DH.2 fighters;[4] less accurately, it is sometimes extended to the whole period of service of the Fokker monoplanes on the Western Front – from the arrival of the first two Fokker E.I fighters at FFA62 in June 1915, until the last Eindeckers in the early German fighter units finally gave way to later types in August–September 1916.[1]

The term "Fokker Scourge" was coined in retrospect by the British press in mid-1916, after the German monoplane fighters had been largely neutralised by the new Allied types.[5] This was not unconnected with the political campaign launched by (among others) the pioneering aviation journalist C. G. Grey and Noel Pemberton Billing M.P., the founder of the Supermarine company and a great enthusiast of aerial warfare, the stated object of which was to end a perceived dominance of the Royal Aircraft Factory in the supply of aircraft to the Royal Flying Corps.[6]

Background

Early air warfare

In early 1915, the Allies (especially the French) were leading the Germans in the fitting of machine guns to aircraft, as aerial warfare developed.[7] The first aircraft used with some success as fighters included the British Vickers F.B.5 and the French Morane-Saulnier L and Morane-Saulnier N.[8] The number of aircraft in front line service was small, and the development of air fighting was rudimentary but the German High Command had ordered the development of machine-gun armed aircraft, to counter those of the Allies, including the aggressive employment of the new armed two-seaters (the "C" types) and "fighter" uses for twin engined aircraft such as the AEG G.II.[1][9]

On 18 April 1915, the Morane-Saulnier L of Roland Garros was captured.[10] From 1 April, Garros had destroyed three German aircraft using the machine, which featured a machine-gun firing forward through the arc of the propeller. Bullets that would have damaged the propeller, were deflected by small wedge-like blades attached to the vulnerable points on each propeller blade.[11] Although Garros attempted to burn his aircraft after force-landing behind German lines, this was not sufficient to conceal the nature of the device. The significance of the deflector blades was immediately appreciated by the German authorities, who quickly requested several aircraft manufacturers, including Anthony Fokker, to produce a copy.[10]

Synchronisation gear

Fokker's answer was the Stangensteuerung (push rod controller), a genuine synchronisation gear. The Stangensteuerung used impulses from a cam on the aircraft engine, to control the firing of the machine-gun so that it did not hit the propeller.[12] This was not the first such gear proposed but was the first to be fitted to an aircraft and proved in flight. In a postwar biography Fokker claimed that he designed and built the gear in 48 hours but this has been largely discounted. It is believed that the gear may have been based on a pre-war patent by Franz Schneider, a Swiss engineer who had worked for Nieuport and the German LVG company and had probably been built by Heinrich Lübbe a Fokker Flugzeugbau engineer.[12][13]

The device was fitted to the most suitable Fokker type, the M.5K, (military designation A.III), of which A.16/15 assigned to Otto Parschau became the prototype of the E.I.[14] Fokker demonstrated A.16/15 to the first few German fighter pilots, including Kurt Wintgens, Oswald Boelcke and Max Immelmann in May and June 1915.[15] The Fokker, with its "Morane" controls, including the over-sensitive balanced elevator and dubious lateral control, was difficult to fly and Parschau, who was experienced on Fokker A types, converted the first pilots to the new fighter.[16][17] The early Eindeckers were supplied in ones and twos to the normal Feldflieger Abteilung (FFA), to protect the reconnaissance machines from Allied machine gun-armed aircraft.[14]

Operational service

Eindecker operations

Fokker Eindecker E.5/15, the last of the pre-production series, is believed to have been first flown in action by Kurt Wintgens of FFA 6.[18] On 1 and 4 July 1915, he reported combats with French Morane L "Parasols"; each time well over the French lines.[17] Wintgens' accounts of the fights were modestly equivocal about the destruction of the Moranes and these victories were never confirmed, although the first matches French records of a Morane forced down on 1 July, near Lunéville with a wounded crew and a damaged engine, with one more three days later.[19] By 15 July, Wintgens had moved to FFA 48 and scored his first recognised victory, another Morane L.[20] Otto Parschau had received E.1/15 to replace the older A.16/15 machine, which became the prototype for the Fokker Eindecker line of aircraft, when it was returned to the Fokker Flugzeugbau factory in Schwerin/Gorries, for further development of the design.[21]

By the end of July 1915, about fifteen Eindeckers were operational with various units, including the five M.5K/MGs and about ten early production E.I airframes.[21] The pilots at first flew the new aircraft as a sideline, when not flying normal oprations in two-seater reconnaissance aircraft.[21] Oswald Boelcke in FFA 62, scored his first victory in an Albatros C.I on 4 July.[22] M.5K/MG prototype airframe E.3/15, the first Eindecker delivered to FFA62, was armed with a Parabellum MG14 gun, synchronized by the troublesome first version of the Fokker gear; at first it was jointly allocated to him and Immelmann, when their "official" duties permitted, allowing them to master the type's difficult handling characteristics and to practice shooting at ground targets.[23] Immelmann was soon allocated a very early production Fokker E.I, E.13/15, one of the first armed with an lMG 08 Spandau machine gun, using the more reliable production version of the Fokker gear.

RFC

The first RFC sightings of the new Fokker aircraft were recorded at the end of July 1915 and continued until the end of September but large numbers of Fokkers were not encountered until October, towards the end of the Battle of Loos (25 September – 14 October).[24] RFC pilots reported that the new fighter could make long, steep dives and that the fixed, synchronised machine-gun was aimed by aiming the aircraft. The Fokker pilot was also assisted by the machine-gun being belt-fed, which obviated the need to change ammunition drums like British observers. Although air fighting was new, the Fokker pilots took to flying high and diving on aircraft, preferably out of the sun, firing a long burst and continuing the dive until well out of range. If the British aircraft had not been shot down, the German pilot could climb again and repeat the process. Immelmann developed a refinement, by zooming after the dive, rolling when vertical to face the opposite way, then turning round to attack again.[25]

The Fokker Scourge is usually considered to have begun on 1 August, when the B.E.2c aircraft of 2 Squadron bombed the base of FFA 62 at 5:00 a.m., waking the German pilots.[23] Boelcke was quickly into the air after the raiders, in E.3/15 Fokker M.5K/MG Eindecker and Immelmann followed in E.13/15. Boelcke suffered a gun jam but Immelmann caught one of the raiders and shot it down.[20] His victory was over a B.E.2c, flown without an observer or Lewis gun, to carry bombs and the pilot fired at Immelmann with an automatic pistol. After about ten minutes of manoeuvring (giving the lie to exaggerated accounts of the stability of B.E.2 aircraft), Immelmann had fired 450 rounds, which riddled the B.E. and wounded the pilot in the arm.[26]

Boelcke and Immelmann continued to score, as did Hans Joachim Buddecke, Ernst von Althaus and Rudolph Berthold, from FFA 23 and Kurt von Crailshein of FFA 53 but the "official" list of 28 victories claimed by Fokker pilots, many of them French, was for the second half of 1915. Thirteen aircraft had been shot down by Immelmann or Boelcke and the other fifteen by seven other Fokker pilots.[9][27] January 1916 brought another further thirteen claims, most of them against the French and twenty more in February, the last month when German air superiority was more or less unchallenged. Most of the victories had been scored by aces, rather than the newer pilots flying the increased number of Fokkers and Pfalz E-type fighters (another copy of the Morane-Saulier H, also called "Fokkers" by French and British airmen).[28] Allied losses were paltry by later standards but the loss of air superiority to Germans, flying a new and supposedly invincible aircraft, caused dismay among the Allied commanders and lowered the morale of Allied airmen. Cecil Lewis in Sagittarius Rising (1936) wrote,

Hearsay and a few lucky encounters had made the machine respected, not to say dreaded by the slow, unwieldy machines then used by us for Artillery Observation and Offensive Patrols.— Cecil Lewis[29]

The Immelmann Turn surprised many pilots and added to British losses but the mystique acquired by the Fokker was greater than its material effect.[30] German aircrews flying other aircraft types, were encouraged to be more aggressive and the British restricted their flying far more than was warranted. During the winter of 1915–1916, the British tried to continue flying but losses caused by bad weather and the Fokkers, led to changes in tactics. On 14 January, RFC HQ issued orders that until better aircraft were delivered, long- and short-range reconnaissance aircraft must have three escorts flying in close formation. If contact with the escorts was lost, the reconnaissance must be cancelled as would photographic reconnaissance to any great distance beyond the front line. The new tactics of concentrating aircraft in time and space had the effect of reducing the size of the RFC, when the demand for information by the army remained the same.[31]

Much effort went into devising formations and a II Wing RFC method was for the reconnaissance aircraft to lead with an escort on each side 500 feet (150 m) higher and another escort behind and 1,000 feet (300 m) above.[Note 1] On 7 February, on a II Wing long-range reconnaissance, the observation pilot flew at 7,500 feet (2,300 m); a German aircraft appeared over Roulers and seven more closed in behind the formation. West of Thourout, two Fokkers arrived and attacked at once, one diving on the reconnaissance machine and the other on an escort. Six more German aircraft appeared over Courtemarck and formed a procession of 14 aeroplanes stalking the British formation. None of the German pilots attacked and all the British aircraft returned, meeting two German aircraft returning from a bombing raid, which mortally wounded one of the British escort pilots. The British ascribed their immunity to attack during the 55-minute flight to the rigid formation, which the two Fokkers were unable to disrupt.[33] On 7 February, a 12 Squadron B.E.2c. was to be escorted by three B.E.2c's, two F.E.2's and a Bristol Scout from the squadron and two more F.E.'s and also four R.E.'s from 21 Squadron. The flight was cancelled but the use of twelve escorts for one reconnaissance aircraft, demonstrated the effect of the Fokkers in drastically reducing the efficiency of RFC operations.[34]

The British changed tactics for the sedate B.E. types, as well as the newer F.E. 2b pusher fighters and began formation flying; the custom of sending the B.E.2c into action without an observer armed with a machine-gun, became far less prevalent.[35] The British and French had to accept that it had become much more hazardous to get aerial photographs to provide intelligence information and ranging data for Allied artillery, in conditions of the new German air superiority.[36] The German Command was concerned that the interrupter gear would be discovered and German fighters were forbidden to fly over Allied lines, a policy which continued for most of the rest of the war. While there were a number of tactical advantages in this approach, the effect of German air superiority was limited by the rarity of German fighters appearing behind the Allied lines.[37][38]

End of the Scourge

The beginning of the end of the Scourge came at the Battle of Verdun (21 February – 20 December). When the battle began, air superiority created by the Fokkers meant that German preparations had mostly been concealed from French aerial reconnaissance. The German aircraft established a Luftsperre, a systematic blockade on the French air squadrons, relying as much on chasing their opponents away as actually shooting them down. During the battle, a new French fighter, Nieuport 11 was assigned to the Verdun front in increasing quantities. The Nieuports were superior to the Eindeckers in almost every respect and soon greatly outnumbered the Eindeckers. The Nieuports arrived at the front in escadrilles de chasse, specialist fighter squadrons, which could operate in formations larger than the singletons or pairs normally flown by the Fokkers and regained air superiority.[39]

The British pressed for more fighters and better designs from England, the first of which was the F.E.2b, early examples of which arrived in France in late 1915 and in the new year, F.E.'s began to replace Vickers F.B.5 Gunbus fighters. The F.E. was relatively fast, had a reliable pusher engine and a good view from the pilot and observer cockpits, from which the observer could also fire over the tail. The Airco DH.2 could fly at 86 miles per hour (138 km/h) at 6,500 feet (2,000 m) and climb to 10,000 feet (3,000 m) in 25 minutes. 20 Squadron, the first full F.E. unit, arrived in France on 23 January 1916, for long-range reconnaissance and escort flying. The Fokker pilots attacked the F.E.'s without hesitation but found that the new aircraft were just as formidable, particularly when formation-flying. 24 Squadron arrived with D.H.2's on 8 February, commanded by Major Lanoe Hawker and began patrols north of the Somme. On 25 April, two of the D.H. pilots were attacked and found that the D.H. could manoeuvre against the Fokkers and a few days later, a D.H. pilot caused a Fokker to crash onto a roof at Bapaume, without opening fire.[40]

In February 1916, Inspektor-Major Friedrich Stempel began to assemble Kampfeinsitzer Kommando (KEK: single-seat battle unit) fighter flights. The KEK were equipped with Eindeckers and other new types like the Pfalz E-series monoplanes, which had been taken from FFA units during the winter of 1915–1916 and combined in pairs and quartets. KEK were formed at Vaux, Avillers, Jametz and Cunel near Verdun and other places on the Western Front, as Luftwachtdienst (aerial guard force) units, consisting only of fighters.[41] Another six D.H.2 squadrons followed and the pushers began to overcome the Fokkers. The French produced the Nieuport 11 tractor aircraft, which was superior to any British or German type and the first British Nieuports were issued to 1 Squadron and 11 Squadron in March.[42]

By March 1916, despite frequent encounters with Fokkers and the success of German Eindecker aces, the Scourge was over.[43] The bogey of the Fokker Eindecker as a fighter was laid in April, when an E.III landed by mistake on a British aerodrome and its performance was found to be very much less than believed.[44] The first British aircraft with a synchroniser gear was a Bristol Scout which arrived on 25 March 1916 and on 24 May, the first Sopwith 1½ Strutter aircraft were flown to France by a flight of 70 Squadron. In the second half of May, German air activity on the British front decreased markedly.[45] The commander of the new Luftstreitkräfte Oberst Hermann von der Lieth-Thomsen reorganised the German air service, which were greatly expanded and concentrated the FFA aircraft in Jagdstaffeln; in August began the replacement of Eindeckers with better aircraft.[46]

End of the Eindecker

The impact of the new Allied types, especially the Nieuport, was of considerable concern to the Fokker pilots.[47] New light D type single-seat biplane fighters, the Fokker D.II and Halberstadt D.II had been under test since late 1915 and by mid-1916, the replacement of the monoplanes with these types had commenced.[48] Some Fokker pilots took to flying captured Nieuports and the German High Command was sufficiently desperate to order the building of Nieuport copies by German firms as the Siemens-Schuckert D.I.[49][50] The last Eindeckers were retired from the Jagdstaffeln by September, when they were hopelessly outmoded as front line fighters, although it is reported that they continued in service in second line roles.

Aftermath

Analysis

Among other British politicians and journalists who grossly exaggerated the material effects of the "Scourge", were the eminent pioneering aviation journalist, C.G. Grey, founder of The Aeroplane one of the first aviation magazines and Noel Pemberton Billing M.P., a notably unsuccessful aircraft designer and manufacturer.[2] Their supposed object was the replacement of the B.E.2c with better aircraft but it took the form of an attack on both the Royal Flying Corps high command and the Royal Aircraft Factory.[1] C. G. Grey had orchestrated a campaign against the Royal Aircraft Factory in the pages of The Aeroplane, going back to its period as the Balloon Factory and well before it had produced any heavier-than-air aircraft.[52]

Before the unsuitability of the B.E.2c for air combat was exposed by the first Fokker aces, criticism was not primarily aimed at the technical quality of Factory aircraft but on the fact that a government body was competing with private industry in Great Britain. When the news of the Fokker monoplane fighters reached him in late 1915, Grey was quick to blame the problems faced by the RFC on past orders for equipment, that the latest developments had rendered obsolete, without suggesting what aircraft might have been ordered instead, even supposing that the rapidity of the development of aviation technology, under the spur of war could have been foreseen.

Pemberton Billing also blamed the initially poor performance of British aircraft manufacturers on what he saw as the favouritism shown by the RFC, which was part of the British army, towards the Royal Aircraft Factory, which while nominally civilian, was also part of the army. Pemberton Billing claimed that,

... hundreds, nay thousands of machines have been ordered which have been referred to by our pilots as "Fokker Fodder" ... I would suggest that quite a number of our gallant officers in the Royal Flying Corps have been rather murdered than killed.— Pemberton Billing[53]

Even among writers who have recognised the hysteria of this version of events, this picture of the Fokker scourge gained considerable currency during the war and afterwards.[Note 2] In 1996 Grosz wrote,

The epithet Fokker Fodder was coined by the British to describe the fate of their aircraft under the guns of the Fokker monoplanes, but given [its] acknowledged mediocrity, it comes as something of a shock to realise how abysmal the level of British aircraft performance, pilot training, and aerial tactics must have been ....— P. M. Grosz[48]

Subsequent operations

The period of Allied air superiority that followed the Fokker Scourge was brief. By August 1916, the KEK formed six months earlier had been disbanded and replaced by Jagdstaffeln, flying the new Albatros D.I fighters. These were once more able to turn the tables on the Allies and were soon inflicting many losses on the RFC, culminating in "Bloody April", during the Battle of Arras (9 April – 16 May 1917).[54] In the following two years, the Allied air forces gradually overwhelmed the Luftstreitkräfte in quality and quantity, until the Germans were only able to gain temporary control over small areas of the Western Front. When this tactic became untenable, development of a new aircraft began, which led to the Fokker D.VII. The new aircraft created another "Fokker Scourge" in the summer of 1918 and Germany was required to surrender all Fokker D.VII's to the Allies, as a condition of the Armistice of Compiègne.

References

Notes

- ↑ From 30 January 1916, each British army had a Royal Flying Corps brigade attached, which was divided into wings, the corps wing with squadrons responsible for close reconnaissance, photography and artillery observation on the front of each army corps and an army wing which by 1917 conducted long-range reconnaissance and bombing, using the aircraft types with the highest performance.[32]

- ↑ Much of this is probably due to the apparent "vindication" of Grey and Pemberton Billing by Bloody April a year later.

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 Franks 2001, p. 1.

- 1 2 Kennett 1991, p. 110.

- ↑ Bruce 1968, v.2, p. 20.

- ↑ Angelucci 1983, p. 53.

- ↑ Robertson 2003, p. 103.

- ↑ Hare 1990, pp. 91–102.

- ↑ Cheesman 1960, p. 177.

- ↑ Bruce 1989, pp. 2–4.

- 1 2 Van Wyngarden 2006, p. 18.

- 1 2 Bruce 1989, p. 3.

- ↑ Cheesman 1960, p. 178.

- 1 2 Grosz 1989, p. 2.

- ↑ Woodman 1989, pp. 180–183.

- 1 2 Gray and Thetford 1961, p. 83.

- ↑ Van Wyngarden 2006, p. 9.

- ↑ Immelmann 1934 (2009), p. 77.

- 1 2 Van Wyngarden 2006, p. 10.

- ↑ Van Wyngarden 2006, p. 11–12.

- ↑ Van Wyngarden 2006, p. 10-12.

- 1 2 Franks 2001, pp. 10–11.

- 1 2 3 Van Wyngarden 2006, p. 12.

- ↑ Van Wyngarden 2006, p. 13.

- 1 2 Van Wyngarden 2006, p. 14.

- ↑ Jones, 2002, p. 144

- ↑ Jones, 2002, p. 150

- ↑ Van Wyngarden 2006, p. 15.

- ↑ Franks 2001, p. 41.

- ↑ Franks 2001, p. 59.

- ↑ Lewis 1977, p. 51.

- ↑ Hoeppner, 1994, p. 38

- ↑ Jones, 2002, pp. 156–157

- ↑ Jones, 2002, pp. 147–148

- ↑ Jones, 2002, pp. 157–158

- ↑ Jones, 2002, p. 158

- ↑ Terraine 1982, p. 199.

- ↑ Franks 2001, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Hoeppner, 1994, p. 41

- ↑ Franks 2001, p. 6.

- ↑ Herris and Pearson 2010, p. 29.

- ↑ Jones, 2002, pp. 158–159

- ↑ Guttman, 2009, p. 9

- ↑ Cheesman 1960, p. 92.

- ↑ Franks 2001, pp. 59–60.

- ↑ Lewis, 1977, p. 52

- ↑ Jones, 2002, pp=161–162, 160

- ↑ Jones, 2002, p. 281

- ↑ Van Wyngarden 2006, p. 51.

- 1 2 Grosz 1996, p. 5.

- ↑ Van Wyngarden 2006, p. 64.

- ↑ Cheesman 1960, p. 166.

- ↑ "Deadly Fokker". Flightglobal. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ↑ Hare 1990, in numerous entries

- ↑ Hare 1990, p. 91.

- ↑ Cheesman 1960, p. 108.

Bibliography

- Angelucci, E., ed. The Rand McNally Encyclopedia of Military Aircraft. New York: The Military Press, 1983. ISBN 0-517-41021-4.

- Bruce, J. M. Morane Saulnier Type L. Berkhamstead, UK: Albatros Productions, 1989. ISBN 0-948414-20-0.

- Bruce, J. M. War Planes of the First World War. London: MacDonald, 1968. ISBN 978-0-356-01473-9.

- Cheesman, E. F. (ed.) Fighter Aircraft of the 1914–1918 War. Letchworth, UK: Harleyford, 1960. OCLC 771602378

- Franks, Norman. Sharks Among Minnows: Germany's First Fighter Pilots and the Fokker Eindecker Period, July 1915 to September 1916. London: Grub Street, 2001. ISBN 978-1-90230-492-2.

- Gray, Peter and Owen Thetford. German Aircraft of the First World War. London: Putman, 1990, First edition 1962. ISBN 978-0-93385-271-6.

- Grosz, P. M. Fokker E.III. Berkhamstead, UK: Albatros Productions, 1989. ISBN 0-948414-19-7.

- Grosz, P. M. Halberstadt Fighters. Berkhamstead, UK: Albatros Productions, 1996. ISBN 0-948414-86-3.

- Guttman, Jon (Summer 2009). "Verdun: The First Air Battle for the Fighter: Prelude and Opening" (PDF). http://www.worldwar1.com. Part 1. The Great War Society. Retrieved 26 May 2014. External link in

|website=(help) - Hare, Paul R. The Royal Aircraft Factory. London: Putnam, 1990. ISBN 0-85177-843-7.

- Herris, Jack and Bob Pearson. Aircraft of World War I: 1914–1918. London: Amber, 2010. ISBN 978-1-90662-666-2.

- Hoeppner, E. W. von Deutschlands Krieg in der Luft: ein Rückblick auf die Entwicklung und die Leistungen unserer Heeres-Luftstreitkräfte im Weltkriege (in German) translation Germany's War in the Air. Battery Press, 1994. original publication: Leipzig: 1921, K. F. Koehle. ISBN 0-89839-195-4.

- Immelmann, Franz (with an appendix by Norman Franks). Immelmann: The Eagle of Lille. Drexel Hill, UK: Casemate, 2009 (originally published in Germany, 1934). ISBN 978-1-932033-98-4.

- Jones, H. A. The War in the Air, Being the Story of the Part Played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force, (volume II). original publication, London: Clarendon Press 1928. London: Imperial War Museum and N & M Press edition, 2002. , access date 12 April 2015 ISBN 1-84342-413-4.

- Lewis, Cecil. Sagittarius Rising. London: Penguin, 1977 (first published 1936). ISBN 0-1400-4367-5.

- Kennett, Lee The First Air War: 1914–1918 New York, Simon & Schuster, 1991. ISBN 0-02-917301-9.

- Robertson, Linda R. The Dream of Civilized Warfare: World War I Flying Aces and the American Imagination Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8166-4270-2.

- Terraine, John. White Heat: The New Warfare 1914–1918. London: Book Club Associates, 1982. ISBN 978-0-85052-331-7.

- Wyngarden, Greg van. Early German Aces of World War I. Botley, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2006. ISBN 978-1-84176-997-4.

- Woodman, Harry. Early Aircraft Armament: The Aeroplane and the Gun up to 1918. London: Arms and Armour Press, 1989. ISBN 0-85368-990-3.

Further reading

- Neumann, G. P. (1920). Die deutschen Luftstreitkräfte im Weltkriege [The German Air Force in the Great War: Its History, Development, Organisation, Aircraft, Weapons and Equipment, 1914–1918] (PDF) (Hodder & Stoughton, abridged translation ed.). Berlin: Mittler & Sohn. OCLC 773250508. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

External links

- The War in the Air - Fighters: The Fokker Scourge

- The Fokker scourge

- Caricature satirising exaggerated view of Fokker Scourge

- The Aeroplane, volume 10, January–March 1916

- An Aviator's Field Book, being the field reports of Oswald Bölcke, from 1 August 1914 – 28 October 1916

| ||||||||||||||||||