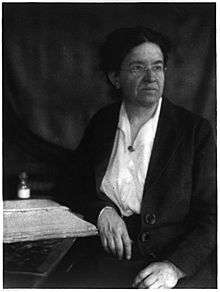

Florence R. Sabin

| Florence R. Sabin | |

|---|---|

Florence R. Sabin | |

| Born |

November 9, 1871 Central City, Colorado |

| Died |

October 3, 1953 (aged 81) Denver, Colorado |

| Nationality | American |

| Fields | Medicine |

| Institutions | Johns Hopkins School of Medicine |

| Alma mater | Johns Hopkins School of Medicine |

| Known for |

pioneer for women in science Sabin Health Laws |

Florence Rena Sabin (November 9, 1871 – October 3, 1953) was an American medical scientist. She was a pioneer for women in science; she was the first woman to hold a full professorship at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, the first woman elected to the National Academy of Sciences, and the first woman to head a department at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research. In her retirement years, she pursued a second career as a public health activist in Colorado, and in 1951 received a Lasker Award for this work.

Biography

.jpg)

Florence Sabin was born in Central City, Colorado, on November 9, 1871, the youngest daughter of Serena Miner and George K. Sabin. Her father was a mining engineer, so the family spent several years in mining communities (Smith College n.d.). At the age of seven, Florence’s mother died from puerperal fever (sepsis), and after her death, Sabin and her sister Mary lived with their Uncle Albert Sabin in Chicago and then with their paternal grandparents in Vermont.

Sabin earned her bachelor's degree from Smith College in 1893. She taught high school mathematics in Denver for two years and zoology at Smith for one year in order to earn enough money for her first year of tuition (National Library of Medicine 1923). Sabin attended the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine as one of fourteen women in her class. The school had opened in 1893 and from the beginning admitted both men and women, in fulfillment of one of the conditions of the gift that made its opening possible.[1]

While at Hopkins, Sabin’s observational skills and perseverance in the laboratory captured the attention of anatomist Franklin P. Mall. Mall encouraged Sabin and helped her to become involved in two projects that would build a solid reputation for her among fellow scientists (Parkhurst 1930). The projects suggested by Franklin P. Mall shaped the future of Sabin’s research and reputation. The first project was to produce a three-dimensional model of a newborn baby’s brainstem which became the focus of the textbook, An Atlas of the Medulla and Midbrain, published in 1901 (Sabin 1901). The second project involved the embryological development of the lymphatic system which proved that the lymphatic system is formed from the embryo’s blood vessels and not other tissues (Smith College n.d.).

Following graduation from the medical school, Sabin obtained an internship at Johns Hopkins Hospital under physician Sir William Osler. Following a one-year internship with Osler, she won a research fellowship in the Department of Anatomy at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine where she worked with Mall (National Library of Medicine n.d.) Soon after, a Fellowship in the Department of Anatomy at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine was created for her.[1] In 1902 she began to teach in the Department of Anatomy at Johns Hopkins. By 1905 she was promoted to associate professor and finally appointed full professor of embryology and histology in 1917, the first woman to become a full professor at a medical college. In 1924 Sabin was elected the first woman president of the American Association of Anatomists and the first lifetime woman member of the National Academy of Sciences.

At Hopkins in 1924 Sabin continued her research on the origins of blood, blood vessels, blood cells, the histology of the brain, and the pathology and immunology of tuberculosis (National Library of Medicine n.d.). In 1924, Sabin’s work on the origins of blood vessels earned her membership in the National Academy of Science (Parkhurst 1930). In September 1925 she became head of the Department of Cellular Studies at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in New York City. Her research focused on the lymphatic system, blood vessels and cells, and tuberculosis.

After retirement

In 1944 she came out of a six-year retirement to accept Colorado governor John Vivian's request to chair a subcommittee on health. Sabin assessed the public health needs of the state and its citizens. She presented her findings that the state was “backward in regard to public health” in a letter to the Governor in April 1945 and as Chair of the Governor’s Committee on Health, becoming a fierce political warrior. Knowing that health legislation had been voted down consistently in the past due to uninterested politicians, she was persistent and relentless in spreading the message of the need for health reform in the state of Colorado. In her early seventies at the time, she did not let eight inches of snow stop her from making it to a speech in support of her cause despite the plea of a health official who was concerned for her safe passage to the speech. In reply, she promptly told him, “pick me up at nine, and don’t forget your rubbers.” She worked to have politicians who opposed health reform defeated in favor of those who showed support.

Her tenacity paid off as the health bills she supported were passed. The results of her efforts were known as the “Sabin Health Laws” which modernized the public health system in Colorado and other states. From her efforts, more hospital beds were made available in Colorado and tuberculosis rates were reduced dramatically. Governor Lee Knous, Vivian’s successor and a supporter of public health, referred to her as a “dynamo” and an “atom bomb” (Bald 1947). In an address to the Illinois Statewide Health Committee in 1947, Sabin said that she was chosen because the Governor had no interest in the idea of public health and appointed “an old lady” because he did not think she would be able to accomplish anything (Sabin 1947). In 1948 she became manager of health and charities for Denver, donating her salary to medical research.

Sabin retired for a second and final time in 1951, although she continued to write and speak on public health. That same year, the University of Colorado’s Department of Medicine dedicated the Florence R. Sabin Building for Research in Cellular Biology in honor of her 80th birthday.(Smith College n.d.). Sabin died of a heart attack on October 3, 1953. She was cremated and her ashes were interred in the Fairmount Mausoleum at Fairmount Cemetery in Denver, Colorado.

In 1959, the state of Colorado donated a statue of Sabin to the National Statuary Hall Collection. In 2005, the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine honored Sabin's legacy by naming one of its four colleges after her.

Research projects and papers

In the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutes Archives, Sabin's collection of papers and medical records from 1903 - 1941 are stored and some even released upon request.[2] The Sophia Smith Collection at Smith College holds many of Dr. Sabin’s papers. Other collections are located in the American Philosophical Society Library in Philadelphia, the University of Colorado Medical School, the Colorado State Historical Society’s Division of Museums, the Rockefeller Institute, and in the Alan Mason Chesney Papers at Johns Hopkins University.

References

Sources

- "Florence Rena Sabin, 1951". Kappa Delta Pi. June 24, 2011.

- National Library of Medicine N.D. (1923). "Changing the face of medicine: Dr. Florence R. Sabin". Journal of Medical Biography (http://www.nlm.nih.gov/changingthefaceofmedicine/physoicians/biography/biography_283.html).*Parkhurst, G. (January 1930). "Dr. Sabin, Scientist". Pictorial ReviewJournal of Medical Biography: 2–3.

- National Library of Medicine (1923). "Profiles in Science: The Florence R. Sabin Papers, Smith College Alumni Questionnaire, 1923". Journal of Medical Biography (https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/RR/Views/AlphaChron/date/10016/).

- Bald, W. (December 1947). "She’s a Bombshell at 76". New York: New York Post.

- Wooley, Charles F (August 2005). "Florence Rena Sabin (1871-1953), William Osler (1849-1919) and tuberculosis". Journal of Medical Biography 13 (3): 162–9.

- Sabin, F.R. (1901). "An atlas of the medulla and midbrain". Journal of Medical Biography (Baltimore: The Friedenwald Company).

- Sabin, F.R. (September 1947). "Profiles in science. Speech read at Illinois Statewide Public Health Committee". Journal of Medical Biography.

- Smith College N.D. "Florence Rena Sabin Papers: Biographical Note". Sophia Smith CollectionJournal of Medical Biography (http://asteria.fivecolleges.edu/findaids/sophiasmith/mnsss110_bioghist.html: Smith College).

- Sabin, Florence R (February 2002). "Preliminary note on the differentiation of angioblasts and the method by which they produce blood-vessels, blood-plasma and red blood-cells as seen in the living chick. 1917". J. Hematother. Stem Cell Res. 11 (1): 5–7. doi:10.1089/152581602753448496. PMID 11846999.

- Harvey, A M (1976). "A new school of anatomy: the story of Franklin P. Mall, Florence R. Sabin, and John B. MacCallum". Johns Hopkins Med. J. Suppl.: 97–113. PMID 801553.

- McGehee Harvey, A (February 1975). "A new school of anatomy: the story of Franklin P. Mall, Florence R. Sabin and John B. MacCallum". The Johns Hopkins Medical Journal 136 (2): 83–84. PMID 1090771.

- "Florence Rena Sabin, "First Lady" Of Colorado". JAMA 186: 1090–1. December 1963. doi:10.1001/jama.1963.03710120072019. PMID 14065365.

- "Florence R. Sabin, M.D". British medical journal 2 (4843): 997–8. October 1953. PMC 2029940. PMID 13094098.

- BASS, E (November 1950). "Florence Rena Sabin, M. D". Journal of the American Medical Women's Association 5 (11): 466–7. PMID 14784430.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Florence R. Sabin. |

- Find a Grave (burial site)

- Florence Rena Sabin Papers American Philosophical Society

- The Florence R. Sabin Papers - Profiles in Science, National Library of Medicine

- Finding Aid, Florence Rena Sabin Papers 1872-1985 - Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Florence R. Sabin |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|