Flintlock

Flintlock is the general term for any firearm based on the flintlock mechanism. The term may also apply to the mechanism itself. Introduced at the beginning of the 17th century, the flintlock rapidly replaced earlier firearm-ignition technologies, such as the doglock, matchlock, and wheellock mechanisms.

It continued to be in common use for over two centuries, replaced by percussion cap and, later, cartridge-based systems in the early-to-mid 19th century. Although long superseded by modern firearms, flintlock weapons enjoy continuing popularity with black-powder shooting enthusiasts.

History

French court gunsmith Marin le Bourgeoys made the first firearm incorporating a true flintlock mechanism for King Louis XIII shortly after his accession to the throne in 1610.[1] The development of firearm lock mechanisms had proceeded from matchlock to wheellock to snaplock to snaphance and miquelet in the previous two centuries, and each type had been an improvement, contributing some design features which were useful. Le Bourgeoys fitted these various features together to create the flintlock mechanism.

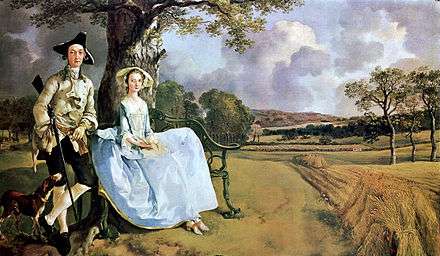

The new system quickly became popular, and was known and used in various forms throughout Europe by 1630. In particular, dragoons serving with the Parliamentarian army in the English Civil War were known to use snaphaunce muskets, or early forms of flintlocks. Examples of early flintlock weapons can be seen in the painting "Marie de' Medici as Bellona" by Rubens (painted around 1622-25).

Various breech-loading flintlocks were developed starting around 1650. The most popular action has a barrel which was unscrewed from the rest of the gun. Obviously this is more practical on pistols because of the shorter barrel length. This type is known as a Queen Anne pistol because it was during her reign that it became popular (although it was actually introduced in the reign of King William III). Another type has a removable screw plug set into the side or top or bottom of the barrel. A large number of sporting rifles were made with this system, as it allowed easier loading compared with muzzle loading with a tight fitting bullet and patch.

One of the more successful was the system built by Isaac de la Chaumette starting in 1704. The barrel could be opened by 3 revolutions of the triggerguard, to which it was attached. The plug stayed attached to the barrel and the ball and powder were loaded from the top. This system was improved in the 1770s by Colonel Patrick Ferguson and 100 experimental rifles used in the American Revolutionary War. The only two flintlock breechloaders to be produced in quantity were the Hall and the Crespi. The first was invented by John Hall and patented c. 1817.[2] It was issued to the U.S Army as the Model 1819 Hall Breech Loading Rifle.[3]

The Hall rifles and carbines were loaded using a combustible paper cartridge inserted into the upward tilting breechblock. Hall rifles leaked gas from the often poorly fitted action. The same problem affected the muskets produced by Giuseppe Crespi and adopted by the Austrian Army in 1771. Nonetheless, the Crespi System was experimented with by the British during the Napoleonic Wars, and percussion Halls guns saw service in the American Civil War.

Flintlock weapons were commonly used until the mid 19th century, when they were replaced by percussion lock systems. Even though they have long been considered obsolete, flintlock weapons continue to be produced today by manufacturers such as Pedersoli, Euroarms, and Armi Sport. Not only are these weapons used by modern re-enactors, but they are also used for hunting, as many U.S. states have dedicated hunting seasons for black-powder weapons, which includes both flintlock and percussion lock weapons.

Subtypes

Flintlocks may be any type of small arm: long gun or pistol, smoothbore or rifle, muzzleloader or breechloader.

Pistols

Flintlock pistols were used as self-defense weapons and as a military arm. Their effective range was short, and they were frequently used as an adjunct to a sword or cutlass. Pistols were usually smoothbore although some rifled pistols were produced.

Flintlock pistols came in a variety of sizes and styles which often overlap and are not well defined, many of the names we use having been applied by collectors and dealers long after the pistols were obsolete. The smallest were less than 6 inches long (15 cm) and the largest were over 20 inches (50 cm). From around the beginning of the 1700s the larger pistols got shorter, so that by the late 1700s the largest would be more like 16 inches long (40 cm). The smallest would fit into a typical pocket or a hand warming muff and could easily be carried by women.

The largest sizes would be carried in holsters across a horse's back just ahead of the saddle. In-between sizes included the coat pocket pistol, or coat pistol, which would fit into a large pocket, the coach pistol, meant to be carried on or under the seat of a coach in a bag or box, and belt pistols, sometimes equipped with a hook designed to slip over a belt or waistband. Larger pistols were called horse pistols. Arguably the most elegant of the pistol designs was the Queen Anne pistol, which was made in all sizes.

Probably the high point of the mechanical development of the flintlock pistol was the British duelling pistol; it was highly reliable, water resistant and accurate. External decoration was minimal but craftsmanship was evident, and the internal works were often finished to a higher degree of craftsmanship than the exterior. Dueling pistols were the size of the horse pistols of the late 1700s, around 16 inches long (40 cm) and were usually sold in pairs along with accessories in a wooden case with compartments for each piece.

Muskets

Flintlock muskets were the mainstay of European armies between 1660 and 1840. A musket was a muzzle-loading smoothbore long gun that was loaded with a round lead ball, but it could also be loaded with shot for hunting. For military purposes, the weapon was loaded with ball, or a mixture of ball with several large shot (called buck and ball), and had an effective range of about 75 to 100 metres. Smoothbore weapons that were designed for hunting birds were called "fowlers." Flintlock muskets tended to be of large caliber and usually had no choke, allowing them to fire full-caliber balls.

Military flintlock muskets tended to weigh approximately ten pounds, as heavier weapons were found to be too cumbersome, and lighter weapons were not rugged or heavy enough to be used in hand-to-hand combat. They were usually designed to be fitted with a bayonet. On flintlocks, the bayonet played a much more significant role, often accounting for a third or more of all battlefield casualties. This is a rather controversial topic in history though, given that casualties list from several battles in the 18th century showed that less than 2% of wounds were caused by bayonets.[4]

Antoine-Henri Jomini, a celebrated military author of the Napoleonic period who served in numerous armies during that period, stated that the majority of bayonet charges in the open resulted with one side fleeing before any contacts were made.[5] Flintlock weapons were not used like modern rifles. They tended to be fired in mass volleys, followed by bayonet charges in which the weapons were used much like the pikes that they replaced. Because they were also used as pikes, military flintlocks tended to be approximately five or six feet in length (without the bayonet attached), and used bayonets that were approximately 18 to 22 inches in length.

Rifles

Some flintlocks were rifled. The spiral grooves of rifling make rifles more accurate and give a longer effective range – but on a muzzle-loading firearm they take more time to load due to the tight-fitting ball, and after repeated shots black powder tended to foul the barrels. Military musketeers couldn't afford to take the time to clean the rifles barrels in between shots and the rifle's greater accuracy was unnecessary when tactics were based on mass volleys. Most military flintlocks were therefore smoothbore. Rifled flintlocks did see some military use by sharpshooters, skirmishers, and other support units; but most rifled flintlocks were used for hunting.

By the late 18th century there were increasing efforts to take advantage of the rifle for military purposes, with specialist rifle units such as the King's Royal Rifle Corps of 1756 and Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort's Own) of 1800. Despite this, smoothbores predominated until the advent of the Minié ball – by which time the percussion cap had made the flintlock obsolete.

In the United States, modifications to small game rifles originally designed in Europe led to the long rifle ("Pennsylvania Rifle" or "Kentucky Rifle,") which due to their long barrels were exceptionally accurate for their time, with an effective range of approximately 250 meters.[6] Since Pennsylvania/Kentucky rifles were used primarily for hunting, they tended to fire smaller caliber rounds, with calibers in the range of .32 to .45 being common. This type of rifle was sometimes referred to as a "pea rifle" since the round ball was approximately the same size as a pea.[7]

The jezail was another example of a long flintlock rifle, but its use in Afghanistan, India, Central Asia and parts of the Middle East was primarily as a military weapon, so tended to fire a larger and heavier round.

Multishot flintlock weapons

Multiple barrels

.jpg)

Because of the time needed to reload (even experts needed 15 seconds to reload a smooth-bore, muzzle-loading musket[8]), flintlocks were sometimes produced with two, three, four or more barrels for multiple shots. These designs tended to be costly to make and were often unreliable and dangerous. While weapons like double barreled shotguns were reasonably safe, weapons like the pepperbox revolver would sometimes fire all barrels simultaneously, or would sometimes just explode in the user's hand. It was often less expensive, safer, and more reliable to carry several single-shot weapons instead.

Single barrel

Some repeater rifles, multishot single barrel pistols, and multishot single barrel revolvers were also made. Notable are the Puckle gun, Mortimer,[9] Kalthoff, Michele Lorenzoni, Abraham Hill, Cookson pistols,[10] the Jennings repeater and the Elisha Collier revolver.

Drawbacks

Flintlocks were prone to many problems, compared to modern weapons. Misfires were common. The flint had to be properly maintained, as a dull or poorly napped piece of flint would not make as much of a spark and would increase the misfire rate dramatically. Moisture was a problem, since moisture on the frizzen or damp powder would prevent the weapon from firing. This meant that flintlock weapons could not be used in rainy or damp weather. Some armies attempted to remedy this by using a leather cover over the lock mechanism, but this proved to have only limited success.[11]

Accidental firing was also a problem for flintlocks. A burning ember left in the barrel could ignite the next powder charge as it was loaded. This could be avoided by waiting between shots for any leftover residue to completely burn. Running a lubricated cleaning patch down the barrel with the ramrod would also extinguish any embers, and would clean out some of the barrel fouling as well. Soldiers on the battlefield could not take these precautions though. They had to fire as quickly as possible, often firing three to four rounds per minute. Loading and firing at such a pace dramatically increased the risk of an accidental discharge.

When a flintlock was fired it sprayed a shower of sparks forwards from the muzzle and another sideways out of the flash-hole. One reason for firing in volleys was to ensure that one man's sparks didn't ignite the next man's powder as he was in the act of loading.

An accidental frizzen strike could also ignite the main powder charge, even if the pan had not yet been primed. Some modern flintlock users will still place a leather cover over the frizzen while loading as a safety measure to prevent this from happening. However, this does slow down the loading time, which prevented safety practices such as this from being used on the battlefields of the past.

The black powder used in flintlocks would quickly foul the barrel, which was a problem for rifles and for smooth bore weapons that fired a tighter fitting round for greater accuracy. Each shot would add more fouling to the barrel, making the weapon more and more difficult to load. Even if the barrel was badly fouled, the flintlock user still had to properly seat the round all the way to the breech of the barrel. Leaving an air gap in between the powder and the round (known as "short starting") was very dangerous, and could cause the barrel to explode.

Handling loose black powder was also dangerous, for obvious reasons. Powder measures, funnels, and other pieces of equipment were usually made out of brass to reduce the risk of creating a spark, which could ignite the powder. Soldiers often used pre-made "cartridges", which unlike modern cartridges were not inserted whole into the weapon. Instead, they were tubes of paper that contained a pre-measured amount of powder and a lead ball. Although paper cartridges were safer to handle than loose powder, their primary purpose was not safety related at all. Instead, paper cartridges were used mainly because they sped up the loading process. A soldier did not have to take the time to measure out powder when using a paper cartridge. He simply tore open the cartridge, used a small amount of powder to prime the pan, then dumped the remaining powder from the cartridge into the barrel.

The black powder used in flintlocks contained sulfur. If the weapon was not cleaned after use, the powder residue would absorb moisture from the air and would combine it with the sulfur to produce sulfuric acid. This acid would erode the inside of the gun barrel and the lock mechanism. Flintlock weapons that were not properly cleaned and maintained would corrode to the point of being destroyed.

Most flintlocks were produced at a time before modern manufacturing processes became common. Even in mass-produced weapons, parts were often handmade. If a flintlock became damaged, or parts wore out due to age, the damaged parts were not easily replaced. Parts would often have to be filed down, hammered into shape, or otherwise modified so that they would fit, making repairs much more difficult. Machine-made, interchangeable parts only began to be used shortly before flintlocks were replaced by caplocks.

Method of operation

- A cock tightly holding a sharp piece of flint is rotated to half-cock, where the sear falls into a safety notch on the tumbler, preventing an accidental discharge.

- The operator loads the gun, usually from the muzzle end, with black powder from a powder flask, followed by lead shot, a round lead ball, usually wrapped in a piece of paper or a cloth patch, all rammed down with a ramrod that is usually stored on the underside of the barrel. Wadding between the charge and the ball was often used in earlier guns.

- The flash pan is primed with a small amount of very finely ground gunpowder, and the flashpan lid or frizzen is closed.

The gun is now in a "primed and loaded" state, and this is how it would typically be carried while hunting or if going into battle.

To fire:

- The cock is further rotated from half-cock to full-cock, releasing the safety lock on the cock.

- The gun is leveled and the trigger is pulled, releasing the cock holding the flint.

- The flint strikes the frizzen, a piece of steel on the priming pan lid, opening it and exposing the priming powder.

- The contact between flint and frizzen produces a shower of sparks (burning pieces of the metal) that is directed into the gunpowder in the flashpan.

- The powder ignites, and the flash passes through a small hole in the barrel (called a vent or touchhole) that leads to the combustion chamber where it ignites the main powder charge, and the gun discharges.

The Royal Infantry and Continental Army used paper cartridges to load their weapons.[12] The powder charge and ball were instantly available to the soldier inside this small paper envelope. To load a flintlock weapon using a paper cartridge, a soldier would

- move the cock to the half-cock position;

- tear the cartridge open with his teeth;

- fill the flashpan half-full with powder, directing it toward the vent;

- close the frizzen to keep the priming charge in the pan;

- pour the rest of the powder down the muzzle and stuff the cartridge in after it;

- take out the ramrod and ram the ball and cartridge all the way to the breech;

- replace the ramrod;

- shoulder the weapon.

The weapon can then be cocked and fired.

Cultural impact

The flintlock mechanism was in main use for both military and civilian use for over 100 years. Not until the Reverend Alexander John Forsyth, a Scottish minister, invented the rudimentary percussion cap system in 1807 did the flintlock system begin to decline in popularity. The percussion-cap system replaced the flintlock's flint and flashpan with a waterproof copper cap that created a spark when struck.

The percussion ignition system was more weatherproof and more reliable than the flintlock. The transition from flintlock to percussion cap was a slow one, even at that, since the percussion system was not widely used until around 1830. The Model 1840 U.S. musket was the last flintlock firearm produced for the U.S. military,[13] although obsolete flintlocks were seeing action in the earliest days of the American Civil War, for example, during the first year of the war, the Army of Tennessee had over 2,000 flintlock muskets in service.

As a result of the flintlock's long active life, it has left lasting marks on the language and on drill and parade. Terms such as: "lock, stock and barrel", "going off half-cocked" and "flash in the pan" remain current in the English language. In addition, the weapon positions and drill commands that were originally devised to standardize carrying, loading and firing a flintlock weapon remain the standard for drill and display (see manual of arms).

-

A flintlock musket being fired

-

Reproduction flintlock musket detail

-

ignition sequence

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Pistols: An Illustrated History of Their Impact" by Jeff Kinard. Published by ABC-CLIO, 2004

- ↑ Flayderman, 1998

- ↑ Flayderman, 1998

- ↑ Lynn, John A. Giant of the Grand Siècle: The French Army, 1610-1715. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1997. Print.

- ↑ Jomini, Antoine Henri. The Art of War. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1971. Print.

- ↑ "What about the rifle?", Popular Science, September 1941

- ↑ "American Rifle: A Treatise, a Text Book, and a Book of Practical Information in the Use of the Rifle" By Townsend Whelen, Publisher: Paladin Press (July 2006)

- ↑ Dennis E. Showalter, William J. Astore, Soldiers' lives through history: Volume 3: The early modern world, p.65, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007 ISBN 0-313-33312-2.

- ↑ Mortimer multishot pistol

- ↑ Flintlock revolvers

- ↑ "Elements of military art and history" By Edouard La Barre Duparcq, Nicolas Édouard Delabarre-Duparcq, 1863

- ↑ Day of Concord and Lexington (French, 1925) p. 25 note 1. See also pp. 27-36.

- ↑ Flayderman, 1998

Bibliography

- Flayderman's Guide to Antique Firearms and Their Values 7th Edition, by Norm Flayderman 1998 Krause Publications ISBN 0-87349-313-3, ISBN 978-0-87349-313-0

- Blackmore, Howard L., Guns and Rifles of the World. Viking Press, New York, 1965

- Blair, Claude, Pistols of the World. Viking Press, New York, 1968

- Lenk, Torsten, The Flintlock: its origin and development, translation by Urquhart, G.A., edited by Hayward, J.F. Bramwell House, New York 1965

External links

- Flintlocks used in the War of 1812

- Flintlock Musket and Pistol Collection A commercial site but has excellent historical information on over 30 different models of flintlocks from the 17th and 18th centuries. Nations covered: France, Germany, United Kingdom, and United States.

- Firearms from the collections of the Prince of Liechtenstein, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on flintlocks

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||