Torus

In geometry, a torus (plural tori) is a surface of revolution generated by revolving a circle in three-dimensional space about an axis coplanar with the circle. If the axis of revolution does not touch the circle, the surface has a ring shape and is called a torus of revolution.

Real-world examples of (approximately) toroidal objects include inner tubes, swim rings, and the surface of a doughnut or bagel.

A torus should not be confused with a solid torus, which is formed by rotating a disk, rather than a circle, around an axis. A solid torus is a torus plus the volume inside the torus. Real-world approximations include doughnuts, vadai or vada, many lifebuoys, and O-rings.

In topology, a ring torus is homeomorphic to the Cartesian product of two circles: S1 × S1, and the latter is taken to be the definition in that context. It is a compact 2-manifold of genus 1. The ring torus is one way to embed this space into three-dimensional Euclidean space, but another way to do this is the Cartesian product of the embedding of S1 in the plane. This produces a geometric object called the Clifford torus, a surface in 4-space.

In the field of topology, a torus is any topological space that is topologically equivalent to a torus.

Geometry

Ring torus

Horn torus

Spindle torus

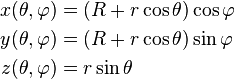

A torus can be defined parametrically by:[1]

where

- θ, φ are angles which make a full circle, so that their values start and end at the same point,

- R is the distance from the center of the tube to the center of the torus,

- r is the radius of the tube.

R is known as the "major radius" and r is known as the "minor radius".[2] The ratio R divided by r is known as the "aspect ratio". A doughnut has an aspect ratio of about 2 to 3.

An implicit equation in Cartesian coordinates for a torus radially symmetric about the z-axis is

or the solution of f(x, y, z) = 0, where

Algebraically eliminating the square root gives a quartic equation,

The three different classes of standard tori correspond to the three possible aspect ratios between R and r:

- When R > r, the surface will be the familiar ring torus.

- R = r corresponds to the horn torus, which in effect is a torus with no "hole".

- R < r describes the self-intersecting spindle torus.

- When R = 0, the torus degenerates to the sphere.

When R ≥ r, the interior

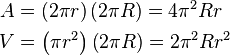

of this torus is diffeomorphic (and, hence, homeomorphic) to a product of an Euclidean open disc and a circle. The surface area and interior volume of this torus are easily computed using Pappus's centroid theorem giving[3]

of this torus is diffeomorphic (and, hence, homeomorphic) to a product of an Euclidean open disc and a circle. The surface area and interior volume of this torus are easily computed using Pappus's centroid theorem giving[3]

These formulas are the same as for a cylinder of length 2πR and radius r, created by cutting the tube and unrolling it by straightening out the line running around the center of the tube. The losses in surface area and volume on the inner side of the tube exactly cancel out the gains on the outer side.

As a torus is the product of two circles, a modified version of the spherical coordinate system is sometimes used. In traditional spherical coordinates there are three measures, R, the distance from the center of the coordinate system, and θ and φ, angles measured from the center point.

As a torus has, effectively, two center points, the centerpoints of the angles are moved; φ measures the same angle as it does in the spherical system, but is known as the "toroidal" direction. The center point of θ is moved to the center of r, and is known as the "poloidal" direction. These terms were first used in a discussion of the Earth's magnetic field, where "poloidal" was used to denote "the direction toward the poles".[4]

In modern use these terms are more commonly used to discuss magnetic confinement fusion devices.

Topology

Topologically, a torus is a closed surface defined as the product of two circles: S1 × S1. This can be viewed as lying in C2 and is a subset of the 3-sphere S3 of radius √2. This topological torus is also often called the Clifford torus. In fact, S3 is filled out by a family of nested tori in this manner (with two degenerate circles), a fact which is important in the study of S3 as a fiber bundle over S2 (the Hopf bundle).

The surface described above, given the relative topology from R3, is homeomorphic to a topological torus as long as it does not intersect its own axis. A particular homeomorphism is given by stereographically projecting the topological torus into R3 from the north pole of S3.

The torus can also be described as a quotient of the Cartesian plane under the identifications

- (x, y) ~ (x+1, y) ~ (x, y+1).

Or, equivalently, as the quotient of the unit square by pasting the opposite edges together, described as a fundamental polygon ABA−1B−1.

.gif)

The fundamental group of the torus is just the direct product of the fundamental group of the circle with itself:

Intuitively speaking, this means that a closed path that circles the torus' "hole" (say, a circle that traces out a particular latitude) and then circles the torus' "body" (say, a circle that traces out a particular longitude) can be deformed to a path that circles the body and then the hole. So, strictly 'latitudinal' and strictly 'longitudinal' paths commute. This might be imagined as two shoelaces passing through each other, then unwinding, then rewinding.

If a torus is punctured and turned inside out then another torus results, with lines of latitude and longitude interchanged. This is equivalent to building a torus from a cylinder, by joining the circular ends together, in two different ways: around the outside like joining two ends of a garden hose, or through the inside like rolling a sock (with the toe cut off). Additionally, if the cylinder was made by gluing two opposite sides of a rectangle together, choosing the other two sides instead will cause the same reversal of orientation.

The first homology group of the torus is isomorphic to the fundamental group (this follows from Hurewicz theorem since the fundamental group is abelian).

Two-sheeted cover

The 2-torus double-covers the 2-sphere, with four ramification points. Every conformal structure on the 2-torus can be represented as a two-sheeted cover of the 2-sphere. The points on the torus corresponding to the ramification points are the Weierstrass points. In fact, the conformal type of the torus is determined by the cross-ratio of the four points.

n-dimensional torus

The torus has a generalization to higher dimensions, the n-dimensional torus, often called the n-torus or hypertorus for short. (This is one of two different meanings of the term "n-torus".) Recalling that the torus is the product space of two circles, the n-dimensional torus is the product of n circles. That is:

The 1-torus is just the circle: T1 = S1. The torus discussed above is the 2-torus, T2. And similar to the 2-torus, the n-torus, Tn can be described as a quotient of Rn under integral shifts in any coordinate. That is, the n-torus is Rn modulo the action of the integer lattice Zn (with the action being taken as vector addition). Equivalently, the n-torus is obtained from the n-dimensional hypercube by gluing the opposite faces together.

An n-torus in this sense is an example of an n-dimensional compact manifold. It is also an example of a compact abelian Lie group. This follows from the fact that the unit circle is a compact abelian Lie group (when identified with the unit complex numbers with multiplication). Group multiplication on the torus is then defined by coordinate-wise multiplication.

Toroidal groups play an important part in the theory of compact Lie groups. This is due in part to the fact that in any compact Lie group G one can always find a maximal torus; that is, a closed subgroup which is a torus of the largest possible dimension. Such maximal tori T have a controlling role to play in theory of connected G. Toroidal groups are examples of protori, which (like tori) are compact connected abelian groups, which are not required to be manifolds.

Automorphisms of T are easily constructed from automorphisms of the lattice Zn, which are classified by invertible integral matrices of size n with an integral inverse; these are just the integral matrices with determinant ±1. Making them act on Rn in the usual way, one has the typical toral automorphism on the quotient.

The fundamental group of an n-torus is a free abelian group of rank n. The k-th homology group of an n-torus is a free abelian group of rank n choose k. It follows that the Euler characteristic of the n-torus is 0 for all n. The cohomology ring H•(Tn, Z) can be identified with the exterior algebra over the Z-module Zn whose generators are the duals of the n nontrivial cycles.

Configuration space

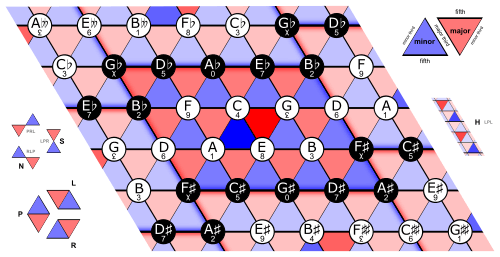

The Tonnetz is only truly a torus if enharmonic equivalence is assumed, so that the (F♯-A♯) segment of the right edge of the repeated parallelogram is identified with the (G♭-B♭) segment of the left edge. If not, it is merely a cylinder.

As the n-torus is the n-fold product of the circle, the n-torus is the configuration space of n ordered, not necessarily distinct points on the circle. Symbolically, Tn = (S1)n. The configuration space of unordered, not necessarily distinct points is accordingly the orbifold Tn/Sn, which is the quotient of the torus by the symmetric group on n letters (by permuting the coordinates).

For n = 2, the quotient is the Möbius strip, the edge corresponding to the orbifold points where the two coordinates coincide. For n = 3 this quotient may be described as a solid torus with cross-section an equilateral triangle, with a twist; equivalently, as a triangular prism whose top and bottom faces are connected with a 1/3 twist (120°): the 3-dimensional interior corresponds to the points on the 3-torus where all 3 coordinates are distinct, the 2-dimensional face corresponds to points with 2 coordinates equal and the 3rd different, while the 1-dimensional edge corresponds to points with all 3 coordinates identical.

These orbifolds have found significant applications to music theory in the work of Dmitri Tymoczko and collaborators (Felipe Posada and Michael Kolinas, et al.), being used to model musical triads.[5][6]

Flat torus

In three dimensions, one can bend a rectangle into a torus, but doing this typically stretches the surface, as seen by the distortion of the checkered pattern |

Seen in stereographic projection a 4D flat torus can be projected into 3-dimensions and rotated on a fixed axis |

The flat torus is a torus with the metric inherited from its representation as the quotient, R2/L, where L is a discrete subgroup of R2 isomorphic to Z2. This gives the quotient the structure of a Riemannian manifold. Perhaps the simplest example of this is when L = Z2 itself: R2/Z2, which can also be described as the Cartesian plane under the identifications (x, y) ~ (x+1, y) ~ (x, y+1). This particular flat torus (and any uniformly scaled version of it as well) is known as the "square" flat torus.

This metric of the square flat torus can also be realised by specific embeddings of the familiar 2-torus into Euclidean 4-space or higher dimensions. Its surface has zero Gaussian curvature everywhere. Its surface is "flat" in the same sense that the surface of a cylinder is "flat". In 3 dimensions one can bend a flat sheet of paper into a cylinder without stretching the paper, but you cannot then bend this cylinder into a torus without stretching the paper (unless you give up some regularity and differentiability conditions, see below).

A simple 4-dimensional Euclidean embedding of a rectangular flat torus (more general than the square one) is as follows:

- (x, y, z, w) = (R cosu, R sinu, P cosv, P sinv)

where R and P are constants determining the aspect ratio. It is diffeomorphic to a regular torus but not isometric. It can not be isometrically embedded into Euclidean 3-space. Mapping it into 3-space requires you to stretch it, in which case it looks like a regular torus, for example, the following map

- (x, y, z) = ((R + Psin(v))cos(u), (R + Psin(v))sin(u), Pcos(v)).

If R and P in the above flat torus form a unit vector <R, P> = <cos(η), sin(η)> then u, v, and η can be used to parameterize the unit 3-sphere in a parameterization associated with the Hopf map. In particular, for certain very specific choices of a square flat torus in the 3-sphere S3, where η = π/4 above, the torus will partition the 3-sphere into two congruent solid tori subsets with the aforesaid flat torus surface as their common boundary. One example is the torus T defined by

T = { (x,y,z,w) ∈ S3 | x2 + y2 = 1/2, z2 + w2 = 1/2 }.

Other tori in S3 having this partitioning property include the square tori of the form Q⋅T, where Q is a rotation of 4-dimensional space R4, or in other words Q is a member of the Lie group SO(4).

It is known that there exists no C2 (twice continuously differentiable) embedding of a flat torus into 3-space. (The idea of the proof is to take a large sphere containing such a flat torus in its interior, and shrink the radius of the sphere until it just touches the torus for the first time. Such a point of contact must be a tangency. But that would imply that part of the torus, since it has zero curvature everywhere, must lie strictly outside the sphere, which is a contradiction.) On the other hand, according to the Nash-Kuiper theorem, proven in the 1950s, an isometric C1 embedding exists. This is solely an existence proof, and does not provide explicit equations for such an embedding.

In April 2012, an explicit C1 (continuously differentiable) embedding of a flat torus into 3-dimensional Euclidean space R3 was found.[7][8][9][10] It is similar in structure to a fractal as it is constructed by repeatedly corrugating a normal torus. Like fractals, it has no defined Gaussian curvature. However, unlike fractals, it does have defined surface normals. It "is" a flat torus in the sense that as metric spaces, it is isometric to a flat square torus. (These infinitely recursive corrugations are used only for embedding into three dimensions; they are not an intrinsic feature of the flat torus.) This is the first time that any such embedding was defined by explicit equations, or depicted by computer graphics.

n-fold torus

In the theory of surfaces there is another object, the n-fold torus, often called the n-holed torus. Instead of the product of n circles, an n-fold torus is the connected sum of n 2-tori. To form a connected sum of two surfaces, remove from each the interior of a disk and "glue" the surfaces together along the disks' boundary circles. To form the connected sum of more than two surfaces, sum two of them at a time until they are all connected. In this sense, an n-torus resembles the surface of n doughnuts stuck together side by side, or a 2-sphere with n handles attached.

An ordinary torus is a 1-fold torus, a 2-fold torus is called a double torus, a 3-fold torus a triple torus, and so on. The n-fold torus is said to be an "orientable surface" of "genus" n, the genus being the number of handles. The 0-fold torus is the 2-sphere.

The classification theorem for surfaces states that every compact connected surface is topologically equivalent to a) the sphere, or b) the n-fold torus with n > 0, or c) the connected sum of n projective planes (that is, projective planes over the real numbers) with n > 0.

double torus |

triple torus |

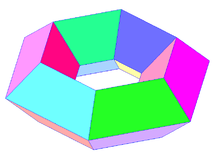

Toroidal polyhedra

Polyhedra with the topological type of a torus are called toroidal polyhedra, and have Euler characteristic V − E + F = 0. For any number holes, the formula generalizes to V − E + F = 2 − 2N, where N is the number of holes.

The term "toroidal polyhedron" is also used for higher-genus polyhedra and for immersions of toroidal polyhedra.

Automorphisms

The homeomorphism group (or the subgroup of diffeomorphisms) of the torus is studied in geometric topology. Its mapping class group (the group of connected components) is isomorphic to the group GL(n, Z) of invertible integer matrices, and can be realized as linear maps on the universal covering space Rn that preserve the standard lattice Zn (this corresponds to integer coefficients) and thus descend to the quotient.

At the level of homotopy and homology, the mapping class group can be identified as the action on the first homology (or equivalently, first cohomology, or on the fundamental group, as these are all naturally isomorphic; also the first cohomology group generates the cohomology algebra):

Since the torus is an Eilenberg–MacLane space K(G, 1), its homotopy equivalences, up to homotopy, can be identified with automorphisms of the fundamental group); that this agrees with the mapping class group reflects that all homotopy equivalences can be realized by homeomorphisms – every homotopy equivalence is homotopic to a homeomorphism – and that homotopic homeomorphisms are in fact isotopic (connected through homeomorphisms, not just through homotopy equivalences). More tersely, the map Homeo(Tn) → SHE(Tn) is 1-connected (isomorphic on path-components, onto fundamental group). This is a "homeomorphism reduces to homotopy reduces to algebra" result.

Thus the short exact sequence of the mapping class group splits (an identification of the torus as the quotient of Rn gives a splitting, via the linear maps, as above):

so the homeomorphism group of the torus is a semidirect product,

The mapping class group of higher genus surfaces is much more complicated, and an area of active research.

Coloring a torus

If a torus is divided into regions, then it is always possible to color the regions with no more than seven colors so that neighboring regions have different colors. (Contrast with the four color theorem for the plane.)

Cutting a torus

A solid torus of revolution (informally, a bagel or donut) can be cut with knives to show how many planes it can be cut into at most n" times

parts.[11]

The initial terms of this sequence, for 0 ≤ n ≤ 10, are as follows:

See also

- Algebraic torus

- Angenent torus

- Annulus (mathematics)

- Bagel

- Clifford torus

- Complex torus

- Doughnut

- Dupin cyclide

- Elliptic curve

- Irrational cable on a torus

- Joint European Torus

- Klein Bottle

- Loewner's torus inequality

- Maximal torus

- Period lattice

- Real projective plane

- Sphere

- Spiric section

- Surface

- Toric lens

- Toric section

- Toric variety

- Toroid

- Toroidal and poloidal

- Torus-based cryptography

- Torus knot

- Umbilic torus

- Villarceau circles

Notes

- NOCIONES DE GEOMETRIA ANALITICA Y ALGEBRA LINEAL, ISBN 978-970-10-6596-9, Author: Kozak Ana Maria, Pompeya Pastorelli Sonia, Verdanega Pedro Emilio, Editorial: McGraw-Hill, Edition 2007, 744 pages, language; Spanish

- Allen Hatcher. Algebraic topology. Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-521-79540-0.

- V.V. Nikulin, I.R.Shafarevich. Geometries and Groups. Springer, 1987. ISBN 3-540-15281-4, ISBN 978-3-540-15281-1.

- "Tore (notion géométrique)" at Encyclopédie des Formes Mathématiques Remarquables

References

- ↑ "Equations for the Standard Torus". Geom.uiuc.edu. 6 July 1995. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ↑ "Torus". hosted by the Spatial website at http://doc.spatial.com/index.php/Main_Page. Spatial Corp. Retrieved 16 November 2014. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ Weisstein, Eric W., "Torus", MathWorld.

- ↑ "Oxford English Dictionary Online". poloidal. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 10 August 2007.

- ↑ Tymoczko, Dmitri (7 July 2006). "The Geometry of Musical Chords" (PDF). Science 313 (5783): 72–74. doi:10.1126/science.1126287. PMID 16825563.

- ↑ Tony Phillips, Tony Phillips' Take on Math in the Media, American Mathematical Society, October 2006

- ↑ Filippelli, Gianluigi (27 April 2012). "Doc Madhattan: A flat torus in three dimensional space". Docmadhattan.fieldofscience.com. doi:10.1073/pnas.1118478109. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ↑ "Mathematicians Produce First-Ever Image of Flat Torus in 3D | Mathematics". Sci-News.com. 18 April 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ↑ "Mathematics : first-ever image of a flat torus in 3D - CNRS Web site - CNRS". Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ↑ "Flat tori finally visualized!". Math.univ-lyon1.fr. 18 April 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W., "Torus Cutting", MathWorld.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Torus. |

- Creation of a torus at cut-the-knot

- "4D torus" Fly-through cross-sections of a four-dimensional torus.

- "Relational Perspective Map" Visualizing high dimensional data with flat torus.

- "Torus Games" Free downloadable games for Windows and Mac OS X that highlight the topology of a torus.

- Polydos

- Séquin, Carlo H. "Topology of a Twisted Torus - Numberphile" (video). Brady Haran. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

|