Fizeau–Foucault apparatus

Fizeau–Foucault apparatus is a term sometimes used to refer to two types of instrument historically used to measure the speed of light. The conflation of the two instrument types arises in part because Hippolyte Fizeau and Léon Foucault had originally been friends and collaborators. They worked together on such projects as using the Daguerreotype process to take images of the Sun between 1843 and 1845[1] and characterizing absorption bands in the infrared spectrum of sunlight in 1847.[2]

In 1834, Charles Wheatstone developed a method of using a rapidly rotating mirror to study transient phenomena, and applied this method to measure the velocity of electricity in a wire and the duration of an electric spark.[3] He communicated to François Arago the idea that his method could be adapted to a study of the speed of light. Arago expanded upon Wheatstone's concept in an 1838 publication, emphasizing the possibility that a test of the relative speed of light in air versus water could be used to distinguish between the particle and wave theories of light.

In 1845, Arago suggested to Fizeau and Foucault that they attempt to measure the speed of light. Sometime in 1849, however, it appears that the two had a falling out, and they parted ways pursuing separate means of performing this experiment.[1] In 1848−49, Fizeau used, not a rotating mirror, but a toothed wheel apparatus to perform an absolute measurement of the speed of light in air. In 1850, Fizeau and Foucault both used rotating mirror devices to perform relative measures of the speed of light in air versus water. Foucault used a scaled-up version of the rotating mirror apparatus to perform an absolute measurement of the speed of light in 1862. Subsequent experiments performed by Marie Alfred Cornu in 1872–76 and by Albert A. Michelson in 1877–1931 used improved versions of the toothed wheel and rotating mirror experiments to make steadily more accurate estimates of the speed of light.

Fizeau's determination of the speed of light

In 1848–49, Hippolyte Fizeau determined the speed of light between an intense light source and a mirror about 8 km distant. The light source was interrupted by a rotating cogwheel with 720 notches that could be rotated at a variable speed of up to hundreds of times a second. (Figure 1) Fizeau adjusted the rotation speed of the cogwheel until light passing through one notch of the cogwheel would be completely eclipsed by the adjacent tooth. Spinning the cogwheel at 3, 5 and 7 times this basic rotation rate also resulted in eclipsing of the reflected light by the cogwheel teeth next in line.[1] Given the rotational speed of the wheel and the distance between the wheel and the mirror, Fizeau was able to calculate a value of 313000 km/s for the speed of light. It was difficult for Fizeau to visually estimate the intensity minimum of the light being blocked by the adjacent teeth,[4] and his value for light's speed was about 5% too high.[5]

The early-to-mid 1800s were a period of intense debate on the particle-versus-wave nature of light. Although the observation of the Arago spot in 1819 may seem to have settled the matter definitively in favor of Fresnel's wave theory of light, various concerns continued to appear to be addressed more satisfactorily by Newton's corpuscular theory.[6] Arago had suggested in 1838 that a differential comparison of the speed of light in air versus water would serve to prove or disprove the wave nature of light. In 1850, racing against Foucault to establish this point, Fizeau engaged L.F.C. Breguet to build a rotary-mirror apparatus in which he split a beam of light into two beams, passing one through water while the other traveled through air. Beaten by Foucault by a mere seven weeks,[7]:117–132 he confirmed that the speed of light was greater as it traveled through air, validating the wave theory of light.[1][Note 1]

Foucault's determination of the speed of light

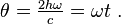

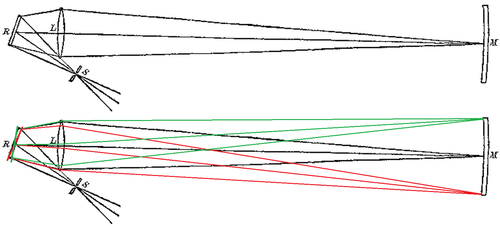

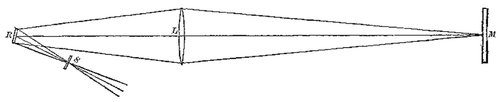

In 1850 and in 1862, Léon Foucault made improved determinations of the speed of light substituting a rotating mirror for Fizeau's toothed wheel. (Figure 2) The apparatus involves light from slit S reflecting off a rotating mirror R, forming an image of the slit on the distant stationary mirror M, which is then reflected back to reform an image of the original slit. If mirror R is stationary, then the slit image will reform at S regardless of the mirror's tilt. The situation is different, however, if R is in rapid rotation.[9]

As the rotating mirror R will have moved slightly in the time it takes for the light to bounce from R to M and back, the light will be deflected away from the original source by a small angle.

| If the distance between mirrors is h, the time between the first and second reflections on the rotating mirror is 2h/c (c = speed of light). If the mirror rotates at a known constant angular rate ω, it changes angle during the light roundtrip by an amount θ given by:

The speed of light is calculated from the observed angle θ, known angular speed ω and measured distance h as |

As seen in Figure 3, the displaced image of the source (slit) is at an angle 2θ from the source direction.[9]

Guided by similar motivations as his former partner, Foucault in 1850 was more interested in settling the particle-versus-wave debate than in determining an accurate absolute value for the speed of light.[6][Note 2] Foucault measured the differential speed of light versus water by inserting a tube filled with water between the rotating mirror and the distant mirror. His experimental results, announced shortly before Fizeau announced his results on the same topic, were viewed as "driving the last nail in the coffin" of Newton's corpuscle theory of light when it showed that light travels more slowly through water than through air.[10] Newton had explained refraction as a pull of the medium upon the light, implying an increased speed of light in the medium.[11] The corpuscular theory of light went into abeyance, completely overshadowed by wave theory.[Note 3] This state of affairs lasted until 1905, when Einstein presented heuristic arguments that under various circumstances, such as when considering the photoelectric effect, light exhibits behaviors indicative of a particle nature.[13]

In contrast to his 1850 measurement, Foucault's 1862 measurement was aimed at obtaining an accurate absolute value for the speed of light, since his concern was to deduce an improved value for the astronomical unit.[6][Note 4] At the time, Foucault was working at the Paris Observatory under Urbain le Verrier. It was le Verrier's belief, based on extensive celestial mechanics calculations, that the consensus value for the speed of light was perhaps 4% too high. Technical limitations prevented Foucault from separating mirrors R and M by more than about 20 meters. Despite this limited path length, Foucault was able to measure the displacement of the slit image (less than 1 mm[4]) with considerable accuracy. In addition, unlike the case with Fizeau's experiment (which required gauging the rotation rate of an adjustable-speed toothed wheel), he could spin the mirror at a constant, chronometrically determined speed. Foucault's measurement confirmed le Verrier's estimate.[7]:227–234 His 1862 figure for the speed of light (298000 km/s) was within 0.6% of the modern value.[14]

Cornu's refinement of the Fizeau experiment

At the behest of the Paris Observatory under le Verrier, Marie Alfred Cornu repeated Fizeau's 1848 toothed wheel measurement in a series of experiments in 1872–76. The goal was to obtain a value for the speed of light accurate to one part in a thousand. Cornu's equipment allowed him to monitor high orders of extinction, up to the 21st order. Instead of estimating the intensity minimum of the light being blocked by the adjacent teeth, a relatively inaccurate procedure, Cornu made pairs of observations on either side of the intensity minima, averaging the values obtained with the wheel spun clockwise and counterclockwise. An electric circuit recorded the wheel rotations on a chronograph chart which enabled precise rate comparisons against the observatory clock, and a telegraph key arrangement allowed Cornu to mark on this same chart the precise moments when he judged that an extinction had been entered or exited.[15] His final experiment was run over a path nearly three times as long as that used by Fizeau, and yielded a figure of 300400 km/s that is within 0.2% of the modern value.[6]

Michelson's refinement of the Foucault experiment

It was seen in Figure 2 that Foucault placed the rotating mirror R as close as possible to lens L so as to maximize the distance between R and the slit S. As R rotates, an enlarged image of slit S sweeps across the face of the distant mirror M. The greater the distance RM, the more quickly that the image sweeps across mirror M and the less light is reflected back. Foucault could not increase the RM distance in his folded optical arrangement beyond about 20 meters without the image of the slit becoming too dim to accurately measure.[8]

Between 1877 and 1931, Albert A. Michelson made multiple measurements of the speed of light. His 1877–79 measurements were performed under the auspices of Simon Newcomb, who was also working on measuring the speed of light. Michelson's setup incorporated several refinements on Foucault's original arrangement. As seen in Figure 5, Michelson placed the rotating mirror R near the principal focus of lens L (i.e. the focal point given incident parallel rays of light). If the rotating mirror R were exactly at the principal focus, the moving image of the slit would remain upon the distant plane mirror M (equal in diameter to lens L) as long as the axis of the pencil of light remained on the lens, this being true regardless of the RM distance. Michelson was thus able to increase the RM distance to nearly 2000 feet. To achieve a reasonable value for the RS distance, Michelson used an extremely long focal length lens (150 feet) and compromised on the design by placing R about 15 feet closer to L than the principal focus. This allowed an RS distance of between 28.5 to 33.3 feet. He used carefully calibrated tuning forks to monitor the rotation rate of the air-turbine-powered mirror R, and he would typically measure displacements of the slit image on the order of 115 mm.[8] His 1879 figure for the speed of light, 299944±51 km/s, was within about 0.05% of the modern value. His 1926 repeat of the experiment incorporated still further refinements such as the use of polygonal prism-shaped rotating mirrors (enabling a brighter image) having from eight through sixteen facets and a 22 mile baseline surveyed to fractional parts-per-million accuracy. His figure of 299,796±4 km/s[16] was only about 4 km/s higher than the current accepted value.[14] Michelson's final 1931 attempt to measure the speed of light in vacuum was interrupted by his death. Although his experiment was completed posthumously by F. G. Pease and F. Pearson, various factors militated against a measurement of highest accuracy, including an earthquake which disturbed the baseline measurement.[17]

Footnotes

- ↑ Given our modern understanding of light, it may be rather difficult to grasp why a particle model of light should have been expected to predict a higher velocity of light in water than in air. (1) Following Descartes, it was believed (falsely) that when a beam of light crosses an air/water interface, the tangential component of its velocity (i.e. its velocity parallel to the surface) should be conserved. If that were so, then the observed fact that the refraction angle is smaller than the incident angle when a beam of light enters water necessarily implies a higher velocity in water. (2) Sound was known to travel faster in solids and liquids than in air. (3) Newton presumed a sort of gravitational attraction of light particles by water in the direction normal to the air/water surface. This would account for Snell's Law and in agreement with Descartes would imply no change in the velocity component parallel to the surface.[6]

- ↑ Contemporary accounts of Fizeau's and Foucault's 1850 experiments refer to their relative speed determinations as a decisive experimentum crucis of emission theory, without mentioning any absolute speed measurements. For example, the Literary Gazette for June 29, 1850 (p 441) reported "The results of the experiments of MM. Fizeau and Brequet [sic], on the comparative quickness of light in air and in water, strongly support the undulatory theory of light. If the lengths traversed by two luminous rays, the one through air and the other through a column of water, were the same for the two media, the time of passing would have been in the ratio of four to three, according to the one or the other theory, and the deviations of the rays produced by the rotation of the mirror would have been in the same ratio." See also the Literary Gazette for September 5, 1857 (p 855).

- ↑ The seemingly complete triumph of wave theory over corpuscular theory required postulating the existence of an all-pervasive luminiferous aether, since otherwise it was impossible to conceive of light crossing empty space. The hypothetical aether, however, was required to have a large number of implausible characteristics. For example, in his eponymous Fizeau experiment of 1851, Fizeau demonstrated that the speed of light through a moving column of water does not equal a simple additive sum of the speed of light through the water plus the speed of the water itself. Other difficulties were glossed over, until the Michelson–Morley experiment of 1887 failed to detect any trace of the aether's effects. In 1892, Hendrik Lorentz postulated an ad hoc set of behaviors for the aether that could explain Michelson and Morley's null result, but the true explanation had to await Einstein's Special Theory of Relativity.[12]

- ↑ The astronomical unit provides the basic distance scale for all measurements of the universe. Ascertaining its precise value was a major goal of 19th century astronomers: the task was in fact identified by the Astronomer Royal, George Airy, in 1857 as "the worthiest problem of Astronomy". Until the 1850s, its value had been determined by relatively inaccurate parallax methods such as measuring the position of Mars against the fixed stars from widely separated points on Earth, or monitoring the rare transits of Venus. An accurate speed of light would enable independent evaluations of the astronomical unit, for instance by reasoning backwards from Bradley's formula for stellar aberration or by reasoning backwards from measurements of the speed of light based on observations of Jupiter's satellites, i.e. Rømer's method.[6]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Hughes, Stephan (2012). Catchers of the Light: The Forgotten Lives of the Men and Women Who First Photographed the Heavens. ArtDeCiel Publishing. pp. 202–223. Archived from the original on 28 October 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ↑ Hearnshaw, J. B. (1987). The Analysis of Starlight: One Hundred and Fifty Years of Astronomical Spectroscopy (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 34–35. ISBN 978-0-521-25548-6. Archived from the original on 28 October 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ↑ Wheatstone, Charles (1834). "An Account of Some Experiments to Measure the Velocity of Electricity and the Duration of Electric Light". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 124: 583–591. Bibcode:1834RSPT..124..583W. doi:10.1098/rstl.1834.0031. Archived from the original on 28 October 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- 1 2 Michelson, Albert A. (1879). "Experimental Determination of the Velocity of Light". Proceedings of the American Association for the Advancement of Science: 71–77. Archived from the original on 28 October 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ↑ Abdul Al-Azzawi (2006). Photonics: principles and practices. CRC Press. p. 9. ISBN 0-8493-8290-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lauginie, P. (2004). "Measuring Speed of Light: Why ? Speed of what?" (PDF). Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference for History of Science in Science Education. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 October 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- 1 2 Tobin, William John (2003). The Life and Science of Leon Foucault: The Man Who Proved the Earth Rotates. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80855-3.

- 1 2 3 4 Michelson, Albert A. (1880). Experimental Determination of the Velocity of Light. Nautical Almanac Office, Bureau of Navigation, Navy Department. Archived from the original on 28 October 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 Ralph Baierlein (2001). Newton to Einstein: the trail of light : an excursion to the wave-particle duality and the special theory of relativity. Cambridge University Press. p. 44; Figure 2.6 and discussion. ISBN 0-521-42323-6. Archived from the original on 28 October 2015.

- ↑ David Cassidy, Gerald Holton, James Rutherford (2002). Understanding Physics. Birkhäuser. ISBN 0-387-98756-8. Archived from the original on 28 October 2015.

- ↑ Bruce H Walker (1998). Optical Engineering Fundamentals. SPIE Press. p. 13. ISBN 0-8194-2764-0.

- ↑ Janssen, Michel & Stachel, John (2010), "The Optics and Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies" (PDF), in John Stachel, Going Critical, Springer, ISBN 1-4020-1308-6, archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2015

- ↑ Niaz, Mansoor; Klassen, Stephen; McMillan, Barbara; Metz, Don (2010). "Reconstruction of the history of the photoelectric effect and its implications for general physics textbooks" (PDF). Science Education 94 (5): 903–931. doi:10.1002/sce.20389. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 October 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- 1 2 Gibbs, Philip. "How is the speed of light measured?". The Original Usenet Physics FAQ. Archived from the original on 28 October 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- 1 2 Cornu, Marie Alfred (1876). Détermination de la vitesse de la lumière: d'après des expériences exécutées en 1874 entre l'Observatoire et Montlhéry. Gauthier-Villars. Archived from the original on 29 October 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ↑ Michelson, A. A. (1927). "Measurement of the Velocity of Light Between Mount Wilson and Mount San Antonio". Astrophysical Journal 65: 1–13. Bibcode:1927ApJ....65....1M. doi:10.1086/143021. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- ↑ Michelson, A. A.; Pease, F. G.; Pearson, F. (1935). "Measurement of the velocity of light in a partial vacuum". Contributions from the Mount Wilson Observatory / Carnegie Institution of Washington 522: 1–36. Bibcode:1935CMWCI.522....1M. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

External links

Relative speed of light measurements

- "Sur un système d'expériences à l'aide duquel la théorie de l'émission et celle des ondes seront soumises à des épreuves décisives." by F. Arago (1838)

- Sur les vitesses relatives de la lumière dans l'air et dans l'eau / par Léon Foucault (1853)

- "Sur l'Experience relative a la vitesse comparative de la lumiere dans l'air et dans l'eau." by H. Fizeau and L. Breguet (1850)

Absolute speed of light measurements

- Sur une experience relative a la vitesse de propagation de la lumière by H. Fizeau (1849)

- Mesure de la vitesse de la lumière ; Étude optique des surfaces / mémoires de Léon Foucault (1913)

- Détermination de la vitesse de la lumière: d'après des expériences exécutées en 1874 entre l'Observatoire et Montlhéry, by M. A. Cornu (1876)

Classroom demonstrations

- Speed of Light (The Foucault Method)

- A modern Fizeau experiment for education and outreach purposes

- Measuring the Speed of Light (video, Foucault method) BYU Physics & Astronomy