Fisk University

| |

Former names | The Fisk Freed Colored School |

|---|---|

| Motto | Her sons and daughters are ever on the altar[1] |

| Type | Private, HBCU |

| Established | 1866 |

| Affiliation | United Church of Christ (historically related) |

| Chairman | Robert W. Norton |

| President | Frank L. Sims (interim president) [2] |

| Provost | Rodney S. Hanley |

Academic staff | 70 |

| Students | 800 |

| Location |

Nashville, Tennessee, USA 36°10′08″N 86°48′17″W / 36.1688°N 86.8047°WCoordinates: 36°10′08″N 86°48′17″W / 36.1688°N 86.8047°W |

| Campus | Urban, 40 acres (16 ha) |

| Colors |

Gold and Blue |

| Athletics |

NAIA – independent (previously GCAC) |

| Nickname | Bulldogs |

| Mascot | The Fisk Bulldog |

| Affiliations |

UNCF ORAU CIC |

| Website | www.fisk.edu |

| |

Fisk University is a historically black university founded in 1866 in Nashville, Tennessee, United States. The 40-acre (160,000 m2) campus is a historic district listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In 1930, Fisk was the first African-American institution to gain accreditation by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. Accreditations for specialized programs quickly followed.

History

In 1866, six months after the end of the American Civil War, leaders of the northern American Missionary Association (AMA) – John Ogden, Reverend Erastus Milo Cravath, field secretary; and Reverend Edward Parmelee Smith – founded the Fisk Free Colored School, for the education of freedmen. AMA support meant the organization tried to use its sources across the country to aid education for freedmen. Enrollment jumped from 200 to 900 in the first several months of the school, indicating freedmen's strong desire for education, with ages of students ranging from seven to seventy. The school was named in honor of General Clinton B. Fisk of the Tennessee Freedmen's Bureau, who made unused barracks available to the school, as well as establishing the first free schools for white and black children in Tennessee. In addition, he endowed Fisk with a total of $30,000.[3] The American Missionary Association's work was supported by the United Church of Christ, which retains an affiliation with the university.[4] Fisk opened to classes on January 9, 1866.[5]

With Tennessee's passage of legislation to support public education, leaders saw a need for training teachers, and Fisk University was incorporated as a normal school for college training in August 1867. Cravath organized the College Department and the Mozart Society, the first musical organization in Tennessee. Rising enrollment added to the needs of the university. In 1870 Adam Knight Spence became principal of the Fisk Normal School. To raise money for the school's education initiatives, his wife Catherine Mackie Spence traveled throughout the United States to set up mission Sunday schools in support of Fisk students, organizing endowments through the AMA.[6] With a strong interest in religion and the arts, Adam Spence supported the start of a student choir. In 1871 the student choir went on a fund-raising tour in Europe; they were the start of the Fisk Jubilee Singers. They toured to raise funds to build the first building for the education of freedmen. They raised nearly $50,000 and funded construction of the renowned Jubilee Hall, now a designated National Historic Landmark.[7] When the American Missionary Association declined to assume the financial responsibility of the Jubilee Singers, Professor George L. White, Treasurer of the University, took the responsibility upon himself and started North in 1871 with his troupe. On April 12, 1873, the Jubilee Singers sailed for England where they sang before a fashionable audience in the presence of the Queen, who expressed her gratification at the performance.[5]

During the 1880s Fisk had an active building program, as well as expanding its curriculum offerings. By the turn of the 20th century, it added black teachers and staff to the university, and a second generation of free blacks entered classes.[7]

From 1915 to 1925, Fayette Avery McKenzie was President of Fisk. McKenzie's tenure, before and after World War I, was during a turbulent period in American history. In spite of many challenges, McKenzie developed Fisk as the premier all Black university in the United States, secured Fisk’s academic recognition as a standard college by the Carnegie Foundation, Columbia University and the University of Chicago, raised a $1 million endowment fund to ensure quality faculty and laid a foundation for Fisk’s accreditation and future success.[8]

In 1947 Fisk heralded its first African-American president with the arrival of Charles Spurgeon Johnson. Johnson was a premier sociologist, a scholar who had been the editor of Opportunity magazine, a noted periodical of the Harlem Renaissance.

In 1952, Fisk was the first predominantly black college to earn a Phi Beta Kappa charter. Organized as the Delta of Tennessee Chapter of the Phi Beta Kappa National Honor Society that December, the chapter inducted its first student members on April 4, 1953.

From 2004 to 2013, Fisk was directed by its 14th president, the Honorable Hazel O'Leary, former Secretary of Energy under President Bill Clinton. She was the second woman to serve as president of the university. On June 25, 2008, Fisk announced that it had successfully raised $4 million during the fiscal year ending June 30. It ended nine years of budget deficits and qualified for a Mellon Foundation challenge grant. However, Fisk still faced significant financial hardship, and claimed that it may need to close its doors unless its finances improve.[9]

H. James Williams, served as president from February 2013 to September 2015. Williams had previously been dean of the Seidman College of Business at Grand Valley State University in Michigan and, before that, an accounting professor at Georgetown University, Florida A&M and Texas Southern University.[10][11] Williams stepped down in September 2015.[12]

Campus

|

Fisk University Historic District | |

| Location |

Roughly bounded by 16th and 18th Aves., Hermosa, Herman and Jefferson Sts. Nashville, Tennessee |

|---|---|

| Architectural style | Italianate; Queen Anne |

| NRHP Reference # | 78002579 |

| Added to NRHP | February 9, 1978 |

Jubilee Hall, which was recently restored, is the oldest and most distinctive structure of Victorian architecture on the 40 acre (160,000 m²) Fisk campus.

-

Students and teachers in training school (between 1890 and 1906)

-

Theological Hall, c. 1900

-

Jubilee Hall

-

Fisk Memorial Chapel

Music, art, and literature collections

Fisk University is the home of a music literature collection founded by the noted Harlem Renaissance figure Carl Van Vechten.

Alfred Stieglitz Collection

Stieglitz’s wife, Georgia O’Keeffe was appointed as Executrix of his estate, upon his death in 1946. The Last Will and Testament of Alfred Stieglitz declared that it was his intent, wish, and desire, that all of the works of Art of his estate (as well as whatever liquid assets his estate possessed; to use in the protection and preservation of those artworks, in perpetuity); be gifted to non-profit corporations (e.g., libraries, museums, educational institutions), for the purpose as stated in the Will; and under the terms and conditions of the Will; to forever, promote the study and interpretation of Modern Art.

With respect to Stieglitz’s wife (Georgia O’Keeffe) then still living; the Will granted her immediate Life Tenancy. Thereby making her the owner and custodian of his entire estate (as his lawful wife), for the duration of her life. And thus, upon Stieglitz’s death, there was no question of custody, or superintending responsibility for the works, while in preparation for their disposition in accordance with the terms and conditions of his Will.

O'Keeffe spent three years meticulously completing the assembly, review and cataloguing of all of his artworks, in preparation for her executing the terms and conditions of Stieglitz's Last Will & Testament; and O'Keeffe petitioned the New York State Court (and was granted its approval) to become the estate's Executrix; under the laws and authority of the courts of the state of New York. In 1949, she facilitated the bequest and apportionment of 99 artworks from the estate in fulfillment of the terms of the Last Will & Testament of Alfred Stieglitz. She also soon afterword (on her own behalf; and as a painter of international renown, in her own right), made an outright gift of two of her own works to the school; and, gifted those works upon terms similar to those of the Stieglitz bequest; with the additional requirement that those works were to forever be known as; and always displayed as, works in the Stieglitz Collection (authored by O'Keeffe) at Fisk University. All the works were subsequently placed on permanent display at the University's Carl Van Vechten Galleries.

In 2005, mounting financial difficulties led the University trustees to vote to sell two of the paintings, O'Keeffe's "Radiator Building" and Marsden Hartley's "Painting No. 3". (Together these were estimated to be worth up to 45 million U.S. dollars.) However, the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, the legal successor in interest of her estate, sued to stop the sale; and, to seek the retrocession of Stieglitz’s entire bequest to Fisk (which O'Keeffe had done as Executrix of Stieglitz's estate) back to the O’Keefe Museum on the basis that the original bequest's terms (in the Stieglitz Will) did not allow the beneficiary of the Stieglitz bequest to ever sell or divide collection as it had been gifted. This condition was done in fulfillment of the donor’s (Stieglitz's) intent that the artworks (as organized and donated as a collective body of work) were first and foremost expressly assembled, collated, and gifted, as a conscious, educative act; to promote the study of the origins of Modern Art in America; at whatever educational institution to whom they had been gifted; and in perpetuity.

The Attorney-General (AG) of Tennessee also filed suit. His challenge was unconnected to the interests the O’Keeffe Museum. The AG intervened on behalf of Tennessee and its responsibility to any bequestor (Stieglitz) to take care that the terms and conditions of his/her last Will & Testament were adhered to; as they related to the contemporary and perpetual responsibilities of any recipient (the University) of the bequest (the donated artwork), that was domiciled within the jurisdiction of the state. The AG interpreted his responsibility to require the State to oppose any attempt to move (permanently or even temporarily) the collection; (in whole, or in part), from Tennessee. As this would, in his judgment, violate two terms of the donor’s bequest. The AG believed that as a matter of public policy charitable bequests were recognized in law because of their beneficial public purpose of promoting and sustaining under the color of law, the perpetual authority, and the immortal power of state sovereignty, protecting acts of charitable bequests in decedent’s estates, in perpetuity.

The terms of the Stieglitz’s bequest as viewed by the Tennessee AG, were as follows. First that the bequest (to the recipient) was to be forever indivisible, once gifted. Prior to their gifting, the works were organized and collated to achieve an instructive, and educational purpose, promoting the study of modern art; wherever, and to whomever, the works were eventually gifted. Their academically careless, or financially driven dismemberment of the gifted collection (after their charitable bequest), would defeat that purpose. Second, the choice of Tennessee’s acknowledged center of higher educational endeavor (Nashville, the “Athens of the South”) as the geographic home of the collection, could only be interpreted as being consonant with the intent of the donor; that the educational purpose of the donation was clearly intended to be met by its location in an acknowledged center, for study in the Western European academic traditions, in the Fine Arts, and in Art History. Fisk University, from its inception in Nashville, had fought and built itself up to be such a center.

At the end of 2007 a plan to share the collection with the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art to earn money was being fought in court by the O'Keeffe Museum.[13] The O'Keeffe Museum's lawsuit failed on appeal, and was withdrawn. The Museum was found to not have standing (law) in a lawsuit, as O'Keeffe herself had formally renounced and surrendered her (and therefore her successors as well) interest as Life Tenant and Executrix of artworks thus gifted to the beneficiaries over fifty years earlier. Thus no residuary interest (for her estate) had existed when she died.

While the AG’s suit continued to have standing, it had to be made consonant with the reality of the cy-près doctrine as that doctrine applied to the current and long-term financial situation of Fisk University. The doctrine, (which applies to charitable trusts, (e.g., Fisk University’s Stieglitz Collection) applies where the original particular purpose of the trust (or its explicit terms and conditions) have become impossible or impracticable (for the grantee to fulfill); and, where the terms of the trust itself, do not specify what is to happen (if, and/or) when, such a situation arises.

Under the doctrine, when this situation occurs a Court (County Chancery Court in Tennessee), may modify the application of the donor’s terms (in their execution); recognizing that, so long as the donor’s underlying intent continues to be satisfied to the maximum extent possible (as the goal); modifications to the explicit terms of the bequest may be made and found to be in order; and not violations of the terms of the bequest to the recipient.

In October 2010, the Court ruled that a 50% stake in the collection could be sold to Crystal Bridges if modifications to the contract were made so that the University could not lose its interest in the collection, nor could the joint venture holding ownership of the collection between the University and Crystal Bridges be based in Delaware (or outside Tennessee Courts jurisdiction). The modified agreement would allow the works to stay at the University until 2013 and then begin a two-year rotation with Crystal Bridges.[14] In April 2012, the Tennessee Supreme Court upheld a lower court decision to allow the sale to move forward. A few months later on August 2, The Davidson County Chancery Court approved a Final Agreed Order that established joint ownership between the University and Crystal Bridges through the newly established Stieglitz Art Collection, LLC. The operating agreement required the University to set aside $3.9 million of the $30 million sale proceeds to be used to establish a fund used for the care and maintenance of the collection at the Van Vechten Gallery at the University.[15][16] The court dispute cost the University $5.8 million in legal fees.[17]

Science programs

Fisk University has a strong record of academic excellence: it has graduated more African Americans who go on to earn PhDs in the natural sciences than any other institution.[18]

Ranking

Fisk University is one of four historically black colleges and universities to earn a tier-one ranking on the list of Best National Liberal Arts Colleges in the 2011 edition of Best Colleges by U.S. News and World Report. Of the 1,400 institutions ranked nationwide, only 246 institutions earned tier one status.

Fisk appears on Parade magazine's "A List" of colleges and universities that offer combined bachelor's and master's degree programs.[19]

In 2010, the Washington Monthly ranked Fisk 29th among America's Best Liberal Arts Colleges. In 2011, CBS Money Watch ranked professors at Fisk University 19th out of 650 colleges and universities in the nation.

According to the Princeton Review, Fisk University is one of America's 373 Best Colleges & Universities.[20]

Athletics

Fisk University teams, nicknamed athletically as the Bulldogs, are part of the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA)[21] Division I level, primarily competing in the Gulf Coast Athletic Conference (GCAC).[22] Men's sports include basketball, cross country, tennis and track & field; while women's sports include basketball, cross country, softball, tennis, track & field and volleyball.

Notable alumni

| Name | Class year | Notability | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dr. John Angelo Lester | 1895 | Professor Emeritus of Physiology, Meharry Medical College | |

| Lil Hardin Armstrong | 1915 | jazz pianist/composer, second wife of Louis Armstrong | |

| Fatima Massaquoi | 1936 | Pioneering Liberian educator | [23] |

| Constance Baker Motley | 1941–1942 | first African-American woman elected to the New York State Senate | |

| Marion Barry | 1960 | former mayor of Washington, D.C. | |

| Mary Frances Berry | former Chair, United States Commission on Civil Rights; former Chancellor University of Colorado at Boulder | ||

| John Betsch | 1967 | Jazz percusionist | |

| Joyce Bolden | first African-American woman to serve on the Commission for Accreditation of the National Association of Schools of Music | ||

| Otis Boykin | 1942 | Inventor, control device for the heart pacemaker | |

| St. Elmo Brady | first African American to earn a doctorate in Chemistry | ||

| Virginia E. Walker Broughton | 1875, 1878 | Author and Baptist missionary | [24][25][26] |

| Cora Brown | first African-American woman elected to a state senate | ||

| Gregory "DJ GB" Byers | 2013 | DJ, Producer | |

| Henry Alvin Cameron | 1896 | Educator, decorated World War I veteran | |

| Elizabeth Hortense (Golden) Canady | past national president of Delta Sigma Theta sorority | ||

| Alfred O. Coffin | first African American to earn a doctorate in zoology | ||

| Malia Cohen | 2001 | San Francisco District 10 Supervisor 2010 – Present | |

| Johnnetta B. Cole | anthropologist, former President of Spelman College and Bennett College | ||

| William L. Dawson (politician) | 1909 | U.S. Congressman (1943–1970) |  |

| Arthur Cunningham | 1951 | Musical Composer, studied at Juilliard and Columbia University | |

| Charles Diggs | United States House of Representatives Michigan (1955–1980) |  | |

| Mahala Ashley Dickerson | 1935 | first black female attorney in the state of Alabama and first black president of the National Association of Women Lawyers | |

| Rel Dowdell | 1993 | acclaimed filmmaker | |

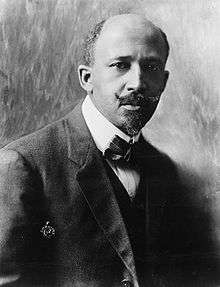

| W. E. B. Du Bois | 1888 | sociologist, scholar, first African-American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard |  |

| Venida Evans | 1969 | Actress, best known for Ikea commercials | |

| Etta Zuber Falconer | 1953 | first African-American woman to receive a Ph.D. in mathematics; former Chair, mathematics department at Spelman College | |

| John Hope Franklin | 1935 | historian, professor, scholar, author of landmark text From Slavery to Freedom |  |

| Victor O. Frazer | United States House of Representatives (1995–1997) | ||

| Alonzo Fulgham | former acting chief and operating officer of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) | ||

| Nikki Giovanni | 1967 | poet, author, professor, scholar |  |

| Louis George Gregory | posthumously, a Hand of the Cause in Bahá'í Faith | ||

| Eliza Ann Grier | 1891 | first African-American female physician in Georgia |  |

| Kevin Hales | Professor, Africologist, Fulbright Scholar, NEH Scholar, Teaching Excellence Professor (Scholar of global African culture) | ||

| Alcee Hastings | U.S. Congressman and former U.S. district court judge | ||

| Roland Hayes | concert singer | ||

| Perry Wilbon Howard | Assistant U.S. Attorney General under President Herbert Hoover | ||

| Elmer Imes | 1903 | Renowned Physicist and Second African-American to earn a Ph.D in Physics | |

| Esther Cooper Jackson | 1940 | Founding editor of Freedomways Journal | |

| Leonard Jackson (actor) | 1952 | Actor, Five on the Black Hand Side; The Color Purple | |

| Robert James | former NFL cornerback | ||

| Judith Jamison | Pioneering Dancer and Choreographer; former artistic Director, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater | ||

| Ted Jarrett | R&B recording artist and producer | ||

| Dr. Charles Jeter | 1971 | father of Derek Jeter | |

| Ben Jobe | 1956 | Legendary basketball coach, Southern University | |

| Lewis Wade Jones | 1931 | Sociologist; Julius Rosenwald Foundation Fellow at Columbia University | |

| Ella Mae Johnson | 1921 | at age 105 years old, Ella Mae Johnson traveled to Washington, DC to attend the inauguration of Barack Obama | |

| Matthew Knowles | 1973 | Father and manager of Beyoncé Knowles | |

| Nella Larsen | 1908 | Novelist, Harlem Renaissance era | |

| Julius Lester | 1960 | Author of children's books and former professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst | |

| David Levering Lewis | Two-time Pulitzer Prize Winner |  | |

| John Lewis | Congressman, civil rights activist, former President of Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) |  | |

| Jimmie Lunceford | 1925 | famous bandleader in the swing era | |

| Aubrey Lyles | 1903 | Vaudville performer | |

| Mandisa | 2001 | Grammy and Dove Award-nominated Christian contemporary singer/songwriter, ninth-place finalist in the fifth season (2006) of American Idol | |

| Patti J. Malone | 1880 | Fisk Jubilee Singer | |

| Louis E. Martin | 1933 | Godfather of Black Politics | |

| Wade H. McCree | 1941 | Second African-American United States Solicitor General; Justice, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit |  |

| Samuel A. McElwee | 1883 | State Senator during the Reconstruction Era and the first African American elected three times to the Tennessee General Assembly | |

| Robert McFerrin | first African American male to sing at the Metropolitan Opera and father of Bobby McFerrin | ||

| Leslie Meek | 1987 | Administrative Law Judge, wife of Congressman Kendrick Meek | |

| Theo Mitchell | 1960 | Senator, South Carolina General Assembly | |

| Undine Smith Moore | first Fisk graduate to receive a scholarship to Juilliard, Pulitzer Prize Nominee | ||

| Diane Nash | founding member of SNCC | ||

| Rachel B. Noel | Politician; first African-American to serve on the Denver Public Schools Board of Education | ||

| Hon. Hazel O'Leary | former U.S. Secretary of Energy |  | |

| Lucius T. Outlaw, Jr. | Philosophy professor at Vanderbilt University[13][27] | ||

| J.O. Patterson, Jr. | 1958 | First African American to occupy the office of Mayor of Memphis. Tennessee State Representative, State Senator, Memphis Councilman, Jurisdictional Bishop in the Church of God in Christ | |

| Helen Phillips | 1928 | first African-American to perform with the Metropolitan Opera Chorus | |

| Annette Lewis Phinazee | 1939 | first black woman to earn a doctorate in library sciences from Columbia University | |

| Alma Powell | wife of Gen. Colin Powell | ||

| Cecelia Cabaniss Saunders | 1903 | director of Harlem YWCA, 1914-1947 | |

| Lorenzo Dow Turner | 1910 | Linguist and Chair, African Studies at Roosevelt University | |

| A. Maceo Walker | 1930 | Businessman, Universal Life Insurance, Tri-State Bank | |

| Ron Walters | 1963 | Scholar of African-American politics, Chair, Afro-American Studies Brandeis University | |

| Margaret Murray Washington | 1890 | Lady Principal of Tuskegee Institute and third wife of Booker T. Washington | |

| Ida B. Wells | American civil rights activist and women's suffrage advocate |  | |

| Charles H. Wesley | 1911 | President of Wilberforce University from 1942 to 1947, and President of Central State College from 1947–1965; third African-American to receive a Ph.D. from Harvard | |

| Kym Whitley | actress, comedienne | ||

| Frederica Wilson | 1963 | U.S. Representative for Florida's 17th congressional district |  |

| Tom Wilson (producer) | 1953 | Music producer, best known for his work with Bob Dylan and Frank Zappa | |

| Frank Yerby | 1938 | first African-American to publish a best-selling novel |

Notable faculty

| Name | Department | Notability | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Camille Akeju | Art | Art historian & museum administrator | [28] |

| Arna Bontemps | Librarian | Head Librarian; Harlem Renaissance Poet | |

| Robert Hayden | United States Poet Laureate 1976–1978 | ||

| Charles Spurgeon Johnson | President | First African American President of Fisk University | |

| Fayette Avery McKenzie | President | Fourth President of Fisk University | |

| Thomas Elsa Jones | President | Fifth President of Fisk University | |

| Percy Lavon Julian | Chemistry | first African-American Chemist and second African-American from any field to become a member of the National Academy of Sciences | |

| Lee Lorch | Mathematics | mathematician and civil rights activist. Fired in 1955 for refusing to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee. | |

| Hon. Hazel O'Leary | President | former U.S. Secretary of Energy | |

| John Oliver Killens | Writer in Residence | Two-time Pulitzer Prize Nominee | |

| Nikki Giovanni | English | author, poet, activist | |

| James Weldon Johnson | Literature | author, poet and civil rights activist, author of Lift Ev'ry Voice and Sing, known as the "Negro National Anthem" | |

| John W. Work III | Music | Choir Director, Ethnomusicologist and scholar of Afro-American folk music | |

| Aaron Douglas | Art | painter, illustrator, muralist | |

| Robert E. Park | Sociology | sociologist of the Chicago School |

References

- ↑ "Welcome". Fisk Memorial Chapel. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ Tamburin, Adam (2015-09-21). "Fisk University president resigns". The Tennessean.

- ↑ Mitchell, Reavis L., Jr., Clinton Bowen Fisk, The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, 2002, accessed 8 July 2012

- ↑ "History of Fisk". Fisk University. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- 1 2 Mitchell, Reavis L., Jr., Fisk University, The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, 2002, accessed 3 Mar 2009

- ↑ Biographical note: Adam Knight Spence, Spence Family Collection, Fisk University Library, accessed 3 Mar 2009. Link via webarchive accessed 15 August 2013.

- 1 2 "Fisk University", The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, 2002, accessed 3 Mar 2009. "When the American Missionary Association declined to assume the financial responsibility of the Jubilee Singers, Professor George L. White, Treasurer of the University, took the responsibility upon himself and started North in 1871 with his troupe. On April 12, 1873, the Jubilee Singers sailed for England where they sang before a fashionable audience in the presence of the Queen, who expressed her gratification at the performance."

- ↑ Christopher L. Nicholson, “To Advance a Race: A Historical Analysis of the Personal Belief, Industrial Philanthropy and Black Liberal Arts Higher Education in Fayette McKenzie’s Presidency at Fisk University, 1915–1925”, Loyola University, Chicago, May 2011, p.299-301, 315–318.

- ↑ "Fisk University Struggles Through Financial Crisis", NPR, September 16, 2010

- ↑ "President", Fisk University webpage. Retrieved 2013-07-29

- ↑ Phillips, Betsy, "H. James Williams Named New President of Fisk University", Nashville Scene, December 7, 2012. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- ↑ Tamburin, Adam (September 21, 2015). "Fisk University president resigns". The Tennessean. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- 1 2 Schelzig, Erik (2007-12-28). "Fisk U. struggles to sell art". USA Today. Associated Press. Alternate AP title: "Search for cash turns into battle over art for Fisk University".

- ↑ Kennedy, Randy (11 October 2010). "Fisk University in New Bid to Gain Approval to Sell Art". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ↑ Pogrebin, Robin (3 August 2012). "Legal Battle Over Fisk University Art Collection Ends". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ↑ Rosenbaum, Lee (CultureGrrl), "News Flash: Court Order to Send Fisk’s Stieglitz Collection to Crystal Bridges in Fall 2013", Arts Journal blog, August 2, 2012.

- ↑ Allyn, Bobby (4 August 2012). "Fisk finalizes deal to sell half-stake of Alfred Stieglitz collection in end to long fight, half-stake sold to Arkansas museum". The Tennessean. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ↑ RESOLUTION NO. RS2008-188: A resolution to recognize and declare Fisk University Day in Nashville, Tennessee on March 19, 2008, Nashville Metropolitan Council, accessed 3 Mar 2009

- ↑ Parade's College "A" List: Combined Bachelor's/Graduate Degree: Fisk University, Parade, accessed 8 July 2012

- ↑ Princeton Review Best Colleges

- ↑ NAIA Member Schools, NAIA webpage. Retrieved 2013-08-28.

- ↑ GCAC Members, GCAC webpage. Retrieved 2013-08-28.

- ↑ Massaquoi, Fatima (2013). Introduction to The Autobiography of an African Princess. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-10250-8.

- ↑ Carter, Tomeiko Ashford, editor (2010). Virginia Broughton: The Life and Writings of a Missionary, The University of Tennessee Press, page xxxix. ISBN 978-1572336964

- ↑ "Biographies". Digital.nypl.org. Retrieved 2012-12-09.

- ↑ "Project MUSE - Virginia Broughton". Muse.jhu.edu. Retrieved 2012-12-09.

- ↑ Vanderbilt University bio. Retrieved 2013-07-22.

- ↑ Bass, Holly (March–April 2006). "Camille Akeju: New Director Seeks to Rejuvenate Anacostia Museum". Crisis: 37–39. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fisk University. |

| ||||||||||||||