Fish processing

The term fish processing refers to the processes associated with fish and fish products between the time fish are caught or harvested, and the time the final product is delivered to the customer. Although the term refers specifically to fish, in practice it is extended to cover any aquatic organisms harvested for commercial purposes, whether caught in wild fisheries or harvested from aquaculture or fish farming.

Larger fish processing companies often operate their own fishing fleets or farming operations. The products of the fish industry are usually sold to grocery chains or to intermediaries. Fish are highly perishable. A central concern of fish processing is to prevent fish from deteriorating, and this remains an underlying concern during other processing operations.

Fish processing can be subdivided into fish handling, which is the preliminary processing of raw fish, and the manufacture of fish products. Another natural subdivision is into primary processing involved in the filleting and freezing of fresh fish for onward distribution to fresh fish retail and catering outlets, and the secondary processing that produces chilled, frozen and canned products for the retail and catering trades.[1]

There is evidence humans have been processing fish since the early Holocene.[2] These days, fish processing is undertaken by artisan fishermen, on board fishing or fish processing vessels, and at fish processing plants.

Overview

Fish is a highly perishable food which needs proper handling and preservation if it is to have a long shelf life and retain a desirable quality and nutritional value.[3] The central concern of fish processing is to prevent fish from deteriorating. The most obvious method for preserving the quality of fish is to keep them alive until they are ready for cooking and eating. For thousands of years, China achieved this through the aquaculture of carp. Other methods used to preserve fish and fish products include[4]

- the control of temperature using ice, refrigeration or freezing

- the control of water activity by drying, salting, smoking or freeze-drying

- the physical control of microbial loads through microwave heating or ionizing irradiation

- the chemical control of microbial loads by adding acids

- oxygen deprivation, such as vacuum packing.

Usually more than one of these methods is used. When chilled or frozen fish or fish products are transported by road, rail, sea or air, the cold chain must be maintained. This requires insulated containers or transport vehicles and adequate refrigeration. Modern shipping containers can combine refrigeration with a controlled atmosphere.[4]

Fish processing is also concerned with proper waste management and with adding value to fish products. There is an increasing demand for ready to eat fish products, or products that do not need much preparation.[4]

Handling the catch

When fish are captured or harvested for commercial purposes, they need some preprocessing so they can be delivered to the next part of the marketing chain in a fresh and undamaged condition. This means, for example, that fish caught by a fishing vessel need handling so they can be stored safely until the boat lands the fish on shore. Typical handling processes are[3]

- transferring the catch from the fishing gear (such as a trawl, net or fishing line) to the fishing vessel

- holding the catch before further handling

- sorting and grading

- bleeding, gutting and washing

- chilling

- storing the chilled fish

- unloading, or landing the fish when the fishing vessel returns to port

The number and order in which these operations are undertaken varies with the fish species and the type of fishing gear used to catch it, as well as how large the fishing vessel is and how long it is at sea, and the nature of the market it is supplying.[3] Catch processing operations can be manual or automated. The equipment and procedures in modern industrial fisheries are designed to reduce the rough handling of fish, heavy manual lifting and unsuitable working positions which might result in injuries.[3]

Handling live fish

An alternative, and obvious way of keeping fish fresh is to keep them alive until they are delivered to the buyer or ready to be eaten. This is a common practice worldwide. Typically, the fish are placed in a container with clean water, and dead, damaged or sick fish are removed. The water temperature is then lowered and the fish are starved to reduce their metabolic rate. This decreases fouling of water with metabolic products (ammonia, nitrite and carbon dioxide) that become toxic and make it difficult for the fish to extract oxygen.[3]

Fish can be kept alive in floating cages, wells and fish ponds. In aquaculture, holding basins are used where the water is continuously filtered and its temperature and oxygen level are controlled. In China, floating cages are constructed in rivers out of palm woven baskets, while in South America simple fish yards are built in the backwaters of rivers. Live fish can be transported by methods which range from simple artisanal methods where fish are placed in plastic bags with an oxygenated atmosphere, to sophisticated systems which use trucks that filter and recycle the water, and add oxygen and regulate temperature.[3]

Preservation

Preservation techniques are needed to prevent fish spoilage and lengthen shelf life. They are designed to inhibit the activity of spoilage bacteria and the metabolic changes that result in the loss of fish quality. Spoilage bacteria are the specific bacteria that produce the unpleasant odours and flavours associated with spoiled fish. Fish normally host many bacteria that are not spoilage bacteria, and most of the bacteria present on spoiled fish played no role in the spoilage.[5] To flourish, bacteria need the right temperature, sufficient water and oxygen, and surroundings that are not too acidic. Preservation techniques work by interrupting one or more of these needs. Preservation techniques can be classified as follows.[6]

Control of temperature

If the temperature is decreased, the metabolic activity in the fish from microbial or autolytic processes can be reduced or stopped. This is achieved by refrigeration where the temperature is dropped to about 0 °C, or freezing where the temperature is dropped below -18 °C. On fishing vessels, the fish are refrigerated mechanically by circulating cold air or by packing the fish in boxes with ice. Forage fish, which are often caught in large numbers, are usually chilled with refrigerated or chilled seawater. Once chilled or frozen, the fish need further cooling to maintain the low temperature. There are key issues with fish cold store design and management, such as how large and energy efficient they are, and the way they are insulated and palletized.[6]

An effective method of preserving the freshness of fish is to chill with ice by distributing ice uniformly around the fish. It is a safe cooling method that keeps the fish moist and in an easily stored form suitable for transport. It has become widely used since the development of mechanical refrigeration, which makes ice easy and cheap to produce. Ice is produced in various shapes; crushed ice and ice flakes, plates, tubes and blocks are commonly used to cool fish.[3] Particularly effective is slurry ice, made from micro crystals of ice formed and suspended within a solution of water and a freezing point depressant, such as common salt.[7]

A more recent development is pumpable ice technology. Pumpable ice flows like water, and because it is homogeneous, it cools fish faster than fresh water solid ice methods and eliminates freeze burns. It complies with HACCP and ISO food safety and public health standards, and uses less energy than conventional fresh water solid ice technologies.[8][9]

-

Fish packed in ice

-

Fish chilling with slurry ice.

-

Fish cooling by pumpable ice

-

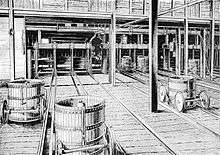

Loading blocks of factory-made ice from a truck to an "ice depot" boat

-

Ice manufactured in this ice house is delivered down the Archimedes screw into the ice hold on the boat, Pittenweem

Control of water activity

The water activity, aw, in a fish is defined as the ratio of the water vapour pressure in the flesh of the fish to the vapour pressure of pure water at the same temperature and pressure. It ranges between 0 and 1, and is a parameter that measures how available the water is in the flesh of the fish. Available water is necessary for the microbial and enzymatic reactions involved in spoilage. There are a number of techniques that have been or are used to tie up the available water or remove it by reducing the aw. Traditionally, techniques such as drying, salting and smoking have been used, and have been used for thousands of years. These techniques can be very simple, for example, by using solar drying. In more recent times, freeze-drying, water binding humectants, and fully automated equipment with temperature and humidity control have been added. Often a combination of these techniques is used.[6]

-

Women drying fish, 1971

-

Dry fish market at Mohanganj

-

Drying stockfish in Iceland

-

Fish barn with fish drying in the sun – Van Gogh 1882.

-

Platforms, called fish flakes, where cod dry in the sun before being packed in salt

-

Remains of Roman fish-salting plant at Neapolis

-

Reconstruction of the Roman fish-salting plant at Neapolis

-

Drying salted fish at Malpe Harbour

-

Salt fish dip at Jakarta

-

Ruins of the Port Eynon Salt House – seawater was boiled to extract salt for preserving fish

Physical control of microbial loads

Heat or ionizing irradiation can be used to kill the bacteria that cause decomposition. Heat is applied by cooking, blanching or microwave heating in a manner that pasteurizes or sterilizes fish products. Cooking or pasteurizing does not completely inactivate microorganisms and may need to be followed with refrigeration to preserve fish products and increase their shelf life. Sterilised products are stable at ambient temperatures up to 40 °C, but to ensure they remain sterilized they need packaging in metal cans or retortable pouches before the heat treatment.[6]

Chemical control of microbial loads

Microbial growth and proliferation can be inhibited by a technique called biopreservation.[10] Biopreservation is achieved by adding antimicrobials or by increasing the acidity of the fish muscle. Most bacteria stop multiplying when the pH is less than 4.5. Acidity is increased by fermentation, marination or by directly adding acids (acetic, citric, lactic) to fish products. Lactic acid bacteria produce the antimicrobial nisin which further enhances preservation. Other preservatives include nitrites, sulphites, sorbates, benzoates and essential oils.[6]

Control of the oxygen reduction potential

Spoilage bacteria and lipid oxidation usually need oxygen, so reducing the oxygen around fish can increase shelf life. This is done by controlling or modifying the atmosphere around the fish, or by vacuum packaging. Controlled or modified atmospheres have specific combinations of oxygen, carbon dioxide and nitrogen, and the method is often combined with refrigeration for more effective fish preservation.[6]

Combined techniques

Two or more of these techniques are often combined. This can improve preservation and reduce unwanted side effects such as the denaturation of nutrients by severe heat treatments. Common combinations are salting/drying, salting/marinating, salting/smoking, drying/smoking, pasteurization/refrigeration and controlled atmosphere/refrigeration.[6] Other process combinations are currently being developed along the multiple hurdle theory.[11]

Automated processes

"The search for higher productivity and the increase of labor cost has driven the development of computer vision technology,[12] electronic scales and automatic skinning and filleting machines."[13]

-

Automatic knives for filleting fish

-

.jpg)

Patent issued to Clarence Birdseye for the production of quick-frozen fish, 1930

-

Processing line for fish fingers

-

.jpg)

Fish feed production in Norway

Waste management

Waste produced during fish processing operations can be solid or liquid.

- Solid wastes: include skin, viscera, fish heads and carcasses (fish bones). Solid waste can be recycled in fish meal plants or it can be treated as municipal waste.[14]

- Liquid wastes: include bloodwater and brine from drained storage tanks, and water discharges from washing and cleaning. This waste may need holding temporarily, and should be disposed of without damage to the environment. How liquid waste should be disposed from fish processing operations depends on the content levels in the waste of solid and organic matter, as well as nitrogen and phosphorus content, and oil and grease content. It also depends on an assessment of parameters such acidity levels, temperature, odour, and biochemical oxygen demand and chemical oxygen demand. The magnitude of waste management issues depends on how much waste volume there is, the nature of the pollutants it carries, the rate at which it is discharged and the capacity of the receiving environment to assimilate the pollutants. Many countries dispose of such liquid wastes through their municipal sewage systems or directly into a waterway. The receiving waterbody should be able to degrade the organic and inorganic waste components in a way that does not damage the aquatic ecosystem.[14]

Treatments can be primary and secondary.

- Primary treatments: use physical methods such as flotation, screening, and sedimentation to remove oil and grease and other suspended solids.[14]

- Secondary treatments: use biological and physicochemical means. Biological treatments use microorganisms to metabolise the organic polluting matter into energy and biomass. "These microorganisms can be aerobic or anaerobic. The most used aerobic processes are activated sludge system, aerated lagoons, trickling filters or bacterial beds and the rotating biological contractors. In anaerobic processes, the anaerobic microorganisms digest the organic matter in tanks to produce gases (mainly methane and CO2) and biomass. Anaerobic digesters are sometimes heated, using part of the methane produced, to maintain a temperature of 30 to 35°C. In the physicochemical treatments, also called coagulation-flocculation, a chemical substance is added to the effluent to reduce the surface charges responsible for particle repulsions in a colloidal suspension, thus reducing the forces that keep its particles apart. This reduction in charge causes flocculation (agglomeration) and particles of larger sizes are settled and clarified effluent is obtained. The sludge produced by primary and secondary treatments is further processed in digesting tanks through anaerobic processes or sprayed over land as a fertilizer. In the latter case, care must be exercised to ensure that the sludge is freed of its pathogens."[14]

Transport

Fish is transported widely in ships, and by land and air, and much fish is traded internationally. It is traded live, fresh, frozen, cured and canned. Live, fresh and frozen fish need special care.[15]

- Live fish: When live fish are transported they need oxygen, and the carbon dioxide and ammonia that result from respiration must not be allowed to build up. Most fish transported live are placed in water supersaturated with oxygen (though catfish can breathe air directly through their gills and body skin, and the climbing perch has special air-breathing organs). The fish are often "conditioned" (starved) before they are transported to reduce their metabolism and increase packing density, and the water can be cooled to further reduce metabolism. Live crustaceans can be packed in wet sawdust to keep the air humid.[15]

- By air: Over five percent of the global fish production is transported by air. Air transport needs special care in preparation and handling and careful scheduling. Airline transport hubs often require cargo transfers under their own tight schedules. This can influence when the product is delivered, and consequently the condition it is in when it is delivered. The air shipment of leaking seafood packages causes corrosion damage to aircraft, and each year, in the US, requires millions of dollars to repair the damage. Most airlines prefer fish that is packed in dry ice or gel, and not packed in ice.[15]

- By land or sea: "The most challenging aspect of fish transportation by sea or by road is the maintenance of the cold chain, for fresh, chilled and frozen products and the optimisation of the packing and stowage density. Maintaining the cold chain requires the use of insulated containers or transport vehicles and adequate quantities of coolants or mechanical refrigeration. Continuous temperature monitors are used to provide evidence that the cold chain has not been broken during transportation. Excellent development in food packaging and handling allow rapid and efficient loading, transport and unloading of fish and fishery products by road or by sea. Also, transport of fish by sea allows for the use of special containers that carry fish under vacuum, modified or controlled atmosphere, combined with refrigeration."[15]

Quality and safety

The International Organization for Standardisation, ISO, is the worldwide federation of national standards bodies. ISO defines quality as "the totality of features and characteristics of a product or service that bear on its ability to satisfy stated or implied needs."(ISO 8402). The quality of fish and fish products depends on safe and hygienic practices. Outbreaks of fish-borne illnesses are reduced if appropriate practices are followed when handling, manufacturing, refrigerating and transporting fish and fish products. Ensuring standards of quality and safety are high also minimizes the post-harvest losses."[16]

"The fishing industry must ensure that their fish handling, processing and transportation facilities meet requisite standards. Adequate training of both industry and control authority staff must be provided by support institutions, and channels for feedback from consumers established. Ensuring high standards for quality and safety is good economics, minimizing losses that result from spoilage, damage to trade and from illness among consumers."[16]

Fish processing highly involves very strict controls and measurements in order to ensure that all processing stages have been carried out hygienically. Thus, all fish processing companies are highly recommended to join a certain type of food safety system. One of the certifications that are commonly known is the Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points (HACCP).

Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points

HACCP is a system which identifies hazards and implements measures for their control. It was first developed in 1960 by NASA to ensure food safety for the manned space program. The main objectives of NASA were to prevent food safety problems and control food borne diseases. HACCP has been widely used by food industry since the late 1970 and now it is internationally recognized as the best system for ensuring food safety.[17]

"The Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) system of assuring food safety and quality has now gained worldwide recognition as the most cost-effective and reliable system available. It is based on the identification of risks, minimizing those risks through the design and layout of the physical environment in which high standards of hygiene can be assured, sets measurable standards and establishes monitoring systems. HACCP also establishes procedures for verifying that the system is working effectively. HACCP is a sufficiently flexible system to be successfully applied at all critical stages -- from harvesting of fish to reaching the consumer. For such a system to work successfully, all stakeholders must cooperate which entails increasing the national capacity for introducing and maintaining HACCP measures. The system's control authority needs to design and implement the system, ensuring that monitoring and corrective measures are put in place."[16]

HACCP is endorsed by the:

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization)

- Codex Alimentarius (a commission of the United Nations)

- FDA (US Food and Drug Administration)[18]

- European Union

- WHO (World Health Organization)

There are seven basic principles:

- Principle 1: Conduct a hazard analysis.

- Principle 2: After assessing all the processing steps, the Critical control point (CCP) is controlled. CCP are points which determine and control significant hazards in a food manufacturing process.

- Principle 3: Set up critical limits in order to ensure that the hazard identified is being controlled effectively.

- Principle 4: Establish a system so as to monitor the CCP.

- Principle 5: Establish corrective actions where the critical limit has not been met. Appropriate actions need to be taken which can be on a short or long-term basis. All records must be sustained accurately.

- Principle 6: Establish authentication procedures so as to confirm if the principles imposed by HACCP documents are being respected effectively and all records are being taken.

- Principle 7: Analyze if the HACCP plan are working effectively.

Final products

Finfish, or parts of finfish, are typically presented physically for marketing in one of the following forms[19]

- whole fish: the fish as it originally came from the water, with no physical processing

- drawn fish: a whole fish which has been eviscerated, that is, had its internal organs removed

- dressed fish: fish that has been scaled and eviscerated, and is ready to cook.

- pan dressed fish: a dressed fish which has had its head, tail, and fins removed, so it will fit in a pan.

- filleted fish: the "fleshy sides of the fish, cut lengthwise from the fish along the backbone. They are usually boneless, although in some fish small bones called “pins” may be present; skin may be present on one side, too. Butterfly fillets may be available. This refers to two fillets held together by the uncut flesh and skin of the belly"[19]

- fish steaks: large dressed fish can be cut into cross section slices, usually half to one inch thick, and usually with a cross section of the backbone

- fish sticks: "are pieces of fish cut from blocks of frozen fillets into portions at least 3/8-inch thick. Sticks are available in fried form ready to heat or frozen raw, coated with batter and breaded, ready to be cooked"[19]

- fish cakes: are "prepared from flaked fish, potatoes, and seasonings, and shaped into cakes, coated with batter, breaded, and then packaged and frozen, ready-to-be-cooked"[19]

- fish fingers

- fish roe

-

Cutting frozen tuna with a band saw

-

Filleting hake

-

Japanese utensils used to fillet large tuna

-

Filleting sole

Value addition

In general value addition means “any additional activity that in one way or the other change the nature of a product thus adding to its value at the time of sale.” Value addition is an expanding sector in the food processing industry, especially in export markets. Value is added to fish and fishery products depending on the requirement of different markets. Globally a transition period is taking place where cooked products are replacing traditional raw products in consumer preference.

"In addition to preservation, fish can be industrially processed into a wide array of products to increase their economic value and allow the fishing industry and exporting countries to reap the full benefits of their aquatic resources. In addition, value processes generate further employment and hard currency earnings. This is more important nowadays because of societal changes that have led to the development of outdoor catering, convenience products and food services requiring fish products ready to eat or requiring little preparation before serving."[13]

"However, despite the availability of technology, careful consideration should be given to the economic feasibility aspects, including distribution, marketing, quality assurance and trade barriers, before embarking on a value addition fish process."[13]

- Surimi: Surimi and surimi-based products are an example of value added products. Surimi is prepared from the mechanically deboned, washed (bleached) and stabilised flesh of fish. "It is an intermediate product used in the preparation of a variety of ready to eat seafood such as kamaboko, fish sausage, crab legs and imitation shrimp products. Surimi-based products are gaining more prominence worldwide, because of the emergence of Japanese restaurants and culinary traditions in North America, Europe and elsewhere. Ideally, surimi should be made from low-value, white fish with excellent gelling ability and which are abundant and available year-round. At present, Alaskan pollack accounts for a large proportion of the surimi supply. Other species, such as sardine, mackerel, barracuda, striped mullet have been successfully used for surimi production."[13]

- Fishmeal and fish oil: "A significant proportion of the world catch (20 percent) is processed into fishmeal and fish oil. Fishmeal is a ground solid product that is obtained by removing most of the water and some or all of the oil from fish or fish waste. This industry was launched in the 19th century, based mainly on surplus catches of herring from seasonal coastal fisheries to produce oil for industrial uses in leather tanning and in the production of soap, glycerol and other non-food products. Presently, it uses small oily fish to produce fishmeal and oil. It is worthy to mention that, only where it is uneconomic or impracticable for human consumption, should the catch be reduced to fishmeal and oil. Indeed, cycling fish through poultry or pigs is a loss because there is a need for 3 kg of edible fish to produce approximately 1 kg of edible chicken or pork."[13]

History

There is evidence humans have been processing fish since the early Holocene. For example, fishbones (c. 8140–7550 BP, uncalibrated) at Atlit-Yam, a submerged Neolithic site off Israel, have been analysed. What emerged was a picture of "a pile of fish gutted and processed in a size-dependent manner, and then stored for future consumption or trade. This scenario suggests that technology for fish storage was already available, and that the Atlit-Yam inhabitants could enjoy the economic stability resulting from food storage and trade with mainland sites."[2]

-

Egyptians bringing in fish and splitting them for salting

-

Medieval smokehouse at Walraversijde, ca. 1465[1]

-

Ice house used to preserve fish at Findhorn

- ^ Tys D and Pieters M (2009) "Understanding a medieval fishing settlement along the southern Northern Sea: Walraversijde, c. 1200–1630" In: Sicking L and Abreu-Ferreira D (Eds.) Beyond the catch: fisheries of the North Atlantic, the North Sea and the Baltic, 900-1850, Brill, pages 91–122. ISBN 978-90-04-16973-9..

See also

Notes

- ↑ Royal Society of Edinburgh (2004) Inquiry into the future of the Scottish fishing industry. 128pp.

- 1 2 Zohar I, Dayan T, Galili E and Spanier E (2001) "Fish processing during the early Holocene: a taphonomic case study from coastal Israel" Journal of Archaeological Science, 28: 1041–1053. doi:10.1006/jasc.2000.0630

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 FAO: Handling of fish and fish products Fisheries and aquaculture department, Rome. Updated 27 May 2005. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 FAO: Processing fish and fish products Fisheries and aquaculture department, Rome. Updated 31 October 2001. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ↑ Huss HH (1988) Quality and quality changes in fresh fish FAO Fisheries Technical Paper 348, Rome. ISBN 92-5-103507-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 FAO: Preservation techniques Fisheries and aquaculture department, Rome. Updated 27 May 2005. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ↑ Kauffeld M, Kawaji M and Egol PW (Eds.) (2005)Handbook on ice slurries: fundamentals and engineering, International Institute of Refrigeration. ISBN 978-2-913149-42-7.

- ↑ "Deepchill™ Variable-State Ice in a Poultry Processing Plant in Korea". Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- ↑ "Results of Liquid Ice Trails aboard Challenge II" (PDF). April 27, 2003. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- ↑ Ananou1 S, Maqueda1 M, Martínez-Bueno1 M and Valdivia1 E (2007) "Biopreservation, an ecological approach to improve the safety and shelf-life of foods" In: A. Méndez-Vilas (Ed.) Communicating Current Research and Educational Topics and Trends in Applied Microbiology, Formatex. ISBN 978-84-611-9423-0.

- ↑ Leistner L and Gould GW (2002) Hurdle technologies: combination treatments for food stability, safety, and quality Springer. ISBN 978-0-306-47263-3.

- ↑ Sun, Da-Wen (Ed.) (2008) Computer vision technology for food quality evaluation Academic Press. Pages 189–208. ISBN 978-0-12-373642-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 FAO: Further processing of fish Fisheries and aquaculture department, Rome. Updated 27 May 2005. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 FAO: Waste management of fish and fish products Fisheries and aquaculture department, Rome. Updated 27 May 2005. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 FAO: Transportation of fish and fish products Fisheries and aquaculture department, Rome. Updated 27 May 2005. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 FAO: Quality and safety of fish and fish products Fisheries and aquaculture department, Rome. Updated 27 September 2001. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ↑ http://haccpalliance.org/alliance/HACCPall.pdf

- ↑ http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/juicgu10.html

- 1 2 3 4 Fin Fish Purdue University. Accessed 18 March 2011.

References

- Bekker-Nielsen T (2005) Ancient fishing and fish processing in the Black Sea region Volume 2 of Black Sea studies, Aarhus University Press, ISBN 978-87-7934-096-1.

- Bremner HA (2003) Safety and Quality Issues in Fish Processing Woodhead Publishing Limited, ISBN 978-1-85573-678-8.

- Brewer DJ and Friedman RF (1989) Fish and Fishing in Ancient Egypt Cairo press: The American University in Cairo. ISBN 978-977-424-224-3

- Cutting CL (1955) Fish saving; a history of fish processing from ancient to modern times, L. Hill.

- Hall GM (1997) Fish processing technology Springer, ISBN 978-0-7514-0273-5.

- Luten JB, Jacobsen C and Bekaert K (2006) Seafood research from fish to dish: quality, safety and processing of wild and farmed fish Wageningen Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-90-8686-005-0.

- Pearson AM and Dutson TR (1999) HACCP in Meat, Poultry and Fish Processing, Volume 10 of Advances in meat research, Springer. ISBN 978-0-8342-1327-2.

- SILVA, A. J. M. (2015), The fable of the cod and the promised sea. About portuguese traditions of bacalhau, in BARATA, F. T- and ROCHA, J. M. (eds.), Heritages and Memories from the Sea, Proceedings of the 1st International Conference of the UNESCO Chair in Intangible Heritage and Traditional Know-How: Linking Heritage, 14-16 January 2015. University of Evora, Évora, pp. 130-143. PDF version

- Shahidi F, Jones Y and Kitts DD (1997) Seafood safety, processing, and biotechnology, Technomic, ISBN 978-1-56676-573-2.

- Stellman JM (ed.) (1998) Chemical, industries and occupations Volume 3 of Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety, International Labour Organization. ISBN 978-92-2-109816-4.

- Stewart H (1982) Indian Fishing: Early Methods on the Northwest Coast University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-88894-332-3.

- Stewart K M (1989) Fishing Sites of North and East Africa in the Late Pleistocene and Holocene. Volume 34 of Cambridge monographs in African archaeology.

- Stewart KM (1994) "Early hominid utilisation of fish resources and implications for seasonality and behaviour" Journal of Human Evolution, 27: 229–245.

- United Nations Development Fund for Women (1993) Fish processing Food Technology Source Book Series (UNIFEM) Series, ISBN 978-1-85339-137-8.

External links

- University of California directory of academic and industry literature

- Fish Products Industry in Canada

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

.png)