First ascent of the Matterhorn

"On 14 July 1865, he set forth from this hotel with his companions and guides, and completed the first successful ascent of the Matterhorn."

The first ascent of the Matterhorn was made by Edward Whymper, Lord Francis Douglas, Charles Hudson, Douglas Hadow, Michel Croz, and two Zermatt guides, Peter Taugwalder father and son, on 14 July 1865. Douglas, Hudson, Hadow and Croz were killed on the descent when Hadow slipped and pulled the other three with him down the north face. Whymper and the Taugwalder guides, who survived, were later accused of having cut the rope below to ensure that they were not dragged down with the others, but the subsequent inquiry found no proof of this and they were acquitted.

The ascent followed a long series of attempts by Edward Whymper and Jean-Antoine Carrel to reach the summit. The first successful expedition was followed shortly after by an Italian expedition that ascended the Italian ridge on the other side of the mountain. The Matterhorn was the last great Alpine peak to be climbed and its first ascent marked the end of the golden age of alpinism.[1]

Background and preparations

In the summer of 1860, Edward Whymper, an athletic, twenty-year-old English artist, visited the Alps for the first time. He had been hired by a London publisher to make sketches and engravings of the scenic mountains along the border of Switzerland and Italy. He was soon interested in mountaineering and decided to attempt the yet unconquered Matterhorn. Whymper soon found that Jean-Antoine Carrel, an Italian guide from the Valtournanche, also had ambitions to be the first to reach the summit of the Matterhorn, and had already made several attempts to climb the mountain. In the years 1861-1865 both made several attempts by the south-west ridge together but became progressively rivals, Carrel patriotically believing that a native Italian like himself and not an Englishman like Whymper should be the first to set foot on the summit.[2]

Meanwhile, in 1863, some leading Italian mountaineers, including Quintino Sella, Bartolomeo Gastaldi and Felice Giordano, gathered at the Castle of Valentino in Turin to discuss the formation of an Alpine Society; and it was secretly proposed there to attempt at once some feat that should bring honour to the institution at its birth. English climbers had deprived Italians of the conquest of Monte Viso, the Piedmontese peak par excellence; the Matterhorn remained as the last unconquered great alpine summit. They knew of the attempts that had been made by the guides of Valtournanche; the groundwork seemed to be well prepared. Neither Gastaldi nor Sella could undertake the work of studying and fitting out the expedition; the honour of this task was offered to Felice Giordano, who accepted it. The foundation of the Italian Alpine Club was formally proclaimed in the same place, on 23 October, after Sella's ascent of Monte Viso, and it is likely that on that occasion the execution of that project, which was looked upon as a national vindication, was again discussed.[3]

Felice Giordano came to Zermatt, and stood for the first time face to face with the Matterhorn. He filled his travelling notebook with sketches, and among his numerous barometrical and geological observations is a note, which in a sketch of the mountain corresponds with the height of the Shoulder, to the effect that: "This is the highest point which has hitherto been reached on the other side"; and further on is this observation: "From information received, we gather that the western face has been ascended to within about five hundred feet of the summit. In order to complete the ascent it would be necessary to cut steps and do other work in the rock for a height of about a hundred feet; eight or ten days, and three or four stone-cutters at twenty francs a day would be required."[3]

Giordano had made serious preparations for the enterprise, including calculations and experiments concerning the strength of ropes, and provided himself with barometers and tents. On 8 July he went up to Valtournanche and met Carrel, who had just returned with some other men (C. Carrel, C. E. Gorret, and J. J. Maquignaz) from an exploration on the mountain. They had come down because the weather was misty, and they had not been able to see very much.[3]

In 1865, Whymper, weary of the defeats he had sustained on the south-west ridge, tried a new way. The stratification of the rocks on the east face seemed to him favourable, and the slope not excessive. His plan of attack was complicated: a huge rock couloir, the base of which lies on the Italian side below the Breuiljoch, on the little Matterhorn glacier, would be ascended to a point high up on the Furggen ridge; from there, traversing the east face of the mountain, he meant to reach the Hörnli (north-east) ridge and follow it to the summit. However, when this route was attempted, the mountain discharged an avalanche of stone upon the climbers, and the ascent failed. His guides refused to make any further attempts by this route.[3]

In the meantime Carrel had spoken with Whymper and had engaged himself for an attempt on the Swiss side. Carrel was engaged to the Englishman until Tuesday, the 11th, inclusive, if the weather were fine; but the weather turned bad and he was thus free. On the morning of the 9th, Whymper, as he was descending to Valtournanche, was surprised to meet Carrel with a traveler, who was coming up with a great deal of baggage. He questioned Carrel, who told him that he would be unable to serve him after the 11th, because he had an engagement with a "family of distinction"; and when Whymper reproached him for not having told him so before, he replied that the engagement dated from a long time back, and till then the day had not been fixed. Whymper had as yet no suspicion that the "distinguished family" was Giordano himself but he became aware of it in Breuil on the morning of the 11th, when the guides had already started to explore, and he learnt that everything had been made ready long before for the expedition which was to prepare the way for Quintino Sella.[3]

Giordano wrote to Sella:[3]

Whymper had arrived two or three days before; as usual, he wished to make the ascent, and had engaged Carrel, who, not having yet had my letters, had agreed, but for a few days only. Fortunately the weather turned bad. Whymper was unable to make his fresh attempt, and Carrel left him and came with me, together with five other picked men who are the best guides in the valley. We immediately sent off our advance guard, with Carrel at its head. In order not to excite remark we took the rope and other materials to Avouil, a hamlet which is very remote and close to the Matterhorn, and this is to be our lower base. Out of six men, four are to work -up above, and two will act continuously as porters, a task which is at least as difficult as the other.I have taken up my quarters at Breuil for the time being. The weather, the god whom we fear and on whom all will depend, has been hitherto very changeable and rather bad. As lately as yesterday morning it was snowing, the night (10th-11th) the men started with the tents, and I hope that by this time they will have reached a great height ; but the weather is turning misty again, and the Matterhorn is still covered; I hope the mists will soon disperse. Weather permitting, I hope in three or four days to know how I stand. Carrel told me not to come up yet, until he should send me word; naturally he wishes to personally make sure of the last bits. As seen from here they do not seem to me to be absolutely inaccessible, but before saying that one must try them; and it is also necessary to ascertain whether we can bivouac at a point much higher than Whymper's highest. As soon as I have any good news I will send a message to St. Vincent, the nearest telegraph office, with a telegram containing a few words; and do you then come at once. Meanwhile, on receipt of the present, please send me a few lines in reply, with some advice, because I am head over ears in difficulty here, what with the weather, the expense, and Whymper. I have tried to keep everything secret, but that fellow, whose life seems to depend on the Matterhorn, is here, suspiciously prying into everything. I have taken all the competent men away from him, and yet he is so enamoured of this mountain that he may go up with others and make a scene. He is here, in this hotel, and I try to avoid speaking to him.

Having rolled up his tent and packed his luggage, Whymper wished to hasten to Zermatt to attempt to reach the summit from that side, but he could find no porters. A young Englishman arrived with a guide. Whymper made himself known to him, and learnt that he was Lord Francis Douglas, who had lately ascended the Ober Gabelhorn; he told him the whole story, and confided his plans to him. Douglas, declaring himself in his turn most anxious to ascend the Matterhorn, agreed to give him his porter, and on the morning of the 12th they started together for the Theodul pass. They descended to Zermatt, sought and engaged Peter Taugwalder, and gave him permission to choose another guide. When they returned to the Monte Rosa Hotel, they encountered Michel Croz who had been hired by Charles Hudson. They had come to Zermatt with the same intention, to attempt to ascend the Matterhorn. Hudson and his friend Douglas Hadow decided to join Whymper and Douglas and that same evening everything was settled; they were to start immediately, the very next day.[3]

Ascent

The party started from Zermatt on 13 July at half-past five. The eight members included Peter Taugwalder and his two sons, Peter and Joseph, who were acting as porters. At 8.20 they reached the chapel at Schwarzsee, where they picked up some material that was left there. They continued along the ridge and at half past eleven they reached the base of the peak. Then they left the ridge and proceeded for half an hour on the east face. Before twelve o'clock they had found a good position for the tent, and at a height of 3,380 metres they set the bivouac. Meanwhile, Croz and young Peter Taugwalder went on to explore the route, in order to save time on the following day. They turned back before 3 p.m., reporting that that ridge offered no great difficulties.[2]

On the morning of the 14th, they assembled together outside the tent and started directly at dawn. Young Peter Taugwalder came on with them as a guide, and his brother, Joseph, returned to Zermatt. They followed the route which had been explored on the previous day, and in a few minutes came in view of the east face:[2]

The whole of this great slope was now revealed, rising for 3,000 feet like a huge natural staircase. Some parts were more, and others were less, easy; but we were not once brought to a halt by any serious impediment, for when an obstruction was met in front it could always be turned to the right or left. For the greater part of the way there was, indeed, no occasion for the rope, and sometimes Hudson led, sometimes myself.

They went up unroped and, at 6.20, reached a height of 12,800 feet. After a half-hour break they proceeded until 9.55, when they stopped for fifty minutes at a height of 14,000 feet. They had arrived at the foot of the much steeper upper peak that lies above the shoulder. Because it was too steep and difficult they had to leave the ridge for the north face. At this point of the ascent Whymper wrote that the less experienced Hadow "required continual assistance". Having overcome these difficulties the group finally arrived near the summit. When they saw that only two hundred feet of easy snow remained, Croz and Whymper detached themselves and reached the top first.[2]

The slope eased off, and Croz and I, dashing away, ran a neck-and-neck race, which ended in a dead heat. At 1.40 p.m. the world was at our feet, and the Matterhorn was conquered. Hurrah! Not a footstep could be seen.

After having checked that no footraces were present on the other extremity of the summit, that might have been reached by the Italian expedition, Whymper, peering over the cliff, saw Carrel and party at a great distance below. They were precisely at this moment 200 metres below, still ascending and dealing with the most difficult parts of the ridge. Whymper and Croz yelled and poured stones down the cliffs to attract their attention. When seeing his rival on the summit, Carrel and party gave up on their attempt and went back to Breuil. A note appears in Felice Giordano's diary, in which, dated 14 July, is the following note : "... At 2 p.m. they saw Whymper and six others on the top; this froze them, as it were, and they all turned and descended. ..." He wrote a letter to his friend Quintino Sella:[3]

Dear Quintino, Yesterday was a bad day, and Whymper, after all, gained the victory over the unfortunate Carrel. Whymper, as I told you, was desperate, and seeing Carrel climbing the mountain, tried his fortune on the Zermatt slope. Every one here, and Carrel above all, considered the ascent absolutely impossible on that side; so we were all easy in our minds. On the 11th Carrel was at work on the mountain, and pitched his tent at a certain height. On the night between the 11th and 12th, and the whole of the 12th, the weather was horrible, and snow on the Matterhorn ; on the 13th weather fair, and yesterday the 14th fine. On the 13th little work was done, and yesterday Carrel might have reached the top, and was perhaps only about 500 or 600 feet below, when suddenly, at about 2 p.m., he saw Whymper and the others already on the summit.

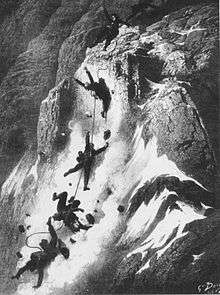

Descent

Whymper and party stayed an hour on the summit. Then they began their descent. Croz descended first, then Hadow, Hudson and Douglas, Taugwalder father, Whymper with Taugwalder son coming last. They climbed down with great care, only one man moving at a time. When they were barely an hour from the summit and were all on the rope, Hadow slipped and fell on Croz, who was in front of him. Croz, who was unprepared, was unable to withstand the shock; they both fell and pulled down Hudson and Douglas. On hearing Croz's shout Whymper and Taugwalder clasped the rocks; they stood firm but the rope broke. Whymper saw them slide down the slope, trying with convulsive hands to stop themselves, and then falling from rock to rock and finally disappearing over the edge of the precipice.[2]

In a letter to the Times Whymper wrote:

As far as I know, at the moment of the accident no one was actually moving. I cannot speak with certainty, neither can the Taugwalders, because the two leading men were partially hidden from our sight by an intervening mass of rock. Poor Croz had laid aside his axe, and, in order to give Mr. Hadow greater security, was absolutely taking hold of his legs and putting his feet, one by one, into their proper positions. From the movements of their shoulders it is my belief that Croz, having done as I have said, was in the act of turning round to go down a step or two himself ; at this moment Mr. Hadow slipped, fell on him, and knocked him over. I heard one startled exclamation from Croz, then saw him and Mr. Hadow flying downwards ; in another moment Hudson was dragged from his steps and Lord F. Douglas immediately after him. All this was the work of a moment ; but immediately we heard Croz's exclamation, Taugwalder and myself planted ourselves as firmly as the rocks would permit ; the rope was tight between us, and the shock came on us as on one man. We held ; but the rope broke midway between Taugwalder and Lord F. Douglas. For two or three seconds we saw our unfortunate companions sliding downwards on their backs, and spreading out their hands endeavouring to save themselves; they then disappeared one by one and fell from precipice to precipice on to the Matterhorn glacier below, a distance of nearly 4,000 feet in height. From the moment the rope broke it was impossible to help them.

After they could fix some rope on firm rocks and secure themselves they were able to proceed and continue the descent. They finally reached a safer place on the ridge towards 6.00 p.m. They looked for traces of their companions and cried to them but in vain. After having seen a curious weather phenomenon in the form of an arch and two crosses (later determined as a fog bow by Whymper), they continued the descent and found a resting place at 9.30 p.m. They could resume the descent at daybreak and reach Zermatt on the morning of Saturday, 15 July.[2]

Rescue

.jpg)

On Saturday, a group of people from Zermatt had started to ascend the Hohlicht heights, above the Zmutt valley, which commanded the plateau of the Matterhorn Glacier. They returned after six hours, and reported that they had seen the bodies lying motionless on the snow. They proposed that the rescuers should leave on Sunday evening, so as to arrive upon the plateau at daybreak on Monday. Whymper and J. M'Cormick decided to start on Sunday morning. The guides of Zermatt, threatened with excommunication by their priests if they failed to attend the early mass, were not willing to go. Other people came to help: J. Robertson, J. Phillpotts and another Briton offered themselves and their guides, Josef Marie Lochmatter and his brother Alexander Lochmatter of St. Niklaus in the canton Valais and Franz Andenmatten. Other guides (Frederic Payot and Jean Tairraz) also volunteered.[2]

At 8.30, after having passed the seracs of the Matterhorn Glacier, Whymper and other reached the top of the plateau. Shortly after they discovered the bodies of Croz, Hadow and Hudson. Of Douglas only a pair of gloves, a belt and boot were found. The bodies were left on the glacier.[2]

The bodies were recovered later on 19 July after an order of the administration. This task was done by 21 men from Zermatt. Croz, Hadow and Hudson were buried near the Church of Zermatt. The body of Douglas has never been found and it was thought to be lost somewhere on the north face.[2] After the accident John Tyndall conceived a complicated device, involving an enormous length of rope for trying to recover the body of Douglas, but it was never used.[4]

Accident controversy

Shortly after the accident Whymper asked Taugwalder to see the rope and to his surprise he saw that it was the oldest and weakest of the ropes they brought and it was only intended as a reserve. All those who had fallen had been tied with a Manila rope, or with a second and equally strong one, and consequently it had been only between the survivors and those who had fallen where the weaker rope had been used. Whymper also had suggested to Hudson that they should have attached a rope to the rocks on the most difficult place, and held it as they descended, as an additional protection. Hudson approved the idea, but it was never done.[2]

Whymper had then to answer grave charges of responsibility and the accusation of having betrayed his companions. An inquiry, presided by Joseph Clemenz, was instituted by the government of the canton of Valais. The guide Peter Taugwalder was accused, tried, and acquitted. Notwithstanding the result of the inquiry, some guides and climbers at Zermatt and elsewhere persisted in asserting that he cut the rope between him and Lord Francis Douglas to save his life.[5]

The accident was long discussed in the media, in Switzerland and abroad. Newspapers all over the world reported the tragedy and no other Alpine event has ever caused more headlines. The emotions were hottest in the United Kingdom, where the grief soon gave way to indignation. Queen Victoria considered banning climbing to all British citizens but decided, after consultation, not to forbid mountaineering.[6]

Whymper wrote at the time to the Secretary of the I.A.C. His letter ends thus :

A single slip, or a single false step, has been the sole cause of this frightful calamity. . . . But, at the same time, it is my belief no accident would have happened had the rope between those who fell been as tight, or nearly as tight, as it was between Taugwalder and myself." Their rope was a weak one; it does not appear to have been cut by the rocks, but to have been broken by the shock and the weight it was called upon to sustain. It is said Croz held Hadow for an instant, and still tried to check the fall even after Hudson and Douglas had been pulled out of their steps, but in vain; his last word was " Impossible ! " so the Taugwalders said.

Portrayals in film

The 1928 silent German-Swiss film Struggle for the Matterhorn portrays the ascent, and starred Luis Trenker as Jean-Antoine Carrel. In 1938 the film was remade in sound as The Mountain Calls (Der Berg ruft!) with Trenker both directing and starring. A separate British version The Challenge was made, also featuring Trenker.

The 1959 film, Third Man on the Mountain [7] also was a fictional account of the ascent.

See also

References

- ↑ Messner, Reinhold (September 2001). The big walls: from the North Face of the Eiger to the South Face of Dhaulagiri. The Mountaineers Books. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-89886-844-9. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Edward Whymper, Scrambles amongst the Alps, 1872.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Guido Rey, The Matterhorn (translated J. E. C. Eaton), London, 1908.

- ↑ Claire Eliane Engel, A History of Mountaineering in the Alps, p. 125.

- ↑ Matterhorn conqueror cleared over fatal falls independent.co.uk. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- ↑ Climb the Matterhorn onderweg-reisemagazine.nl. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- ↑ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0053352/?ref_=fn_al_tt_1

External links

- Der Berg ruft! is available for free download at the Internet Archive (subtitles in French)

- The Challenge on YouTube