First Sino-Japanese War

| First Sino-Japanese War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 630,000 men | 240,616 men | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 35,000 dead or wounded |

1,132 dead, 3,758 wounded 285 died of wounds 11,894 died of disease | ||||||||

| First Sino-Japanese War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 甲午戰爭 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 甲午战争 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||

| Japanese | Japan–Qing War | ||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Chinese |

War of Jiawu – referring to the year 1894 under the traditional sexagenary system | ||||||

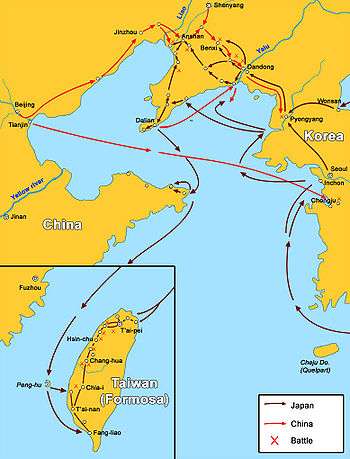

The First Sino-Japanese War (1 August 1894 – 17 April 1895) was fought between the Qing Empire of China and the Empire of Japan, primarily over control of Korea. After more than six months of unbroken successes by Japanese land and naval forces and the loss of the Chinese port of Weihaiwei, the Qing government sued for peace in February 1895.

The war demonstrated the failure of the Qing Empire's attempts to modernize its military and fend off threats to its sovereignty, especially when compared with Japan's successful Meiji Restoration.[1] For the first time, regional dominance in East Asia shifted from China to Japan; the prestige of the Qing Empire, along with the classical tradition in China, suffered a major blow. The humiliating loss of Korea as a vassal state sparked an unprecedented public outcry. Within China, the defeat was a catalyst for a series of political upheavals led by Sun Yat-sen and Kang Youwei, culminating in the 1911 Xinhai Revolution.

The war is commonly known in China as the War of Jiawu (simplified Chinese: 甲午战争; traditional Chinese: 甲午戰爭; pinyin: Jiǎwǔ Zhànzhēng), referring to the year (1894) as named under the traditional sexagenary system of years. In Japan, it is called the Japan–Qing War (Nisshin sensō (日清戦争)). In Korea, where much of the war took place, it is called the Qing–Japan War (Korean: 청일전쟁; Hanja: 淸日戰爭).

Background

After two centuries, the Japanese policy of seclusion under the shoguns of the Edo period came to an end when the country was forced open to trade by American intervention in 1854. The years following the Meiji Restoration of 1868 and the fall of the Shogunate had seen Japan transform itself from a feudal society into a modern industrial state. The Japanese had sent delegations and students around the world to learn and assimilate Western arts and sciences, with the intention of making Japan an equal to the Western powers.[2] Korea continued to try to exclude foreigners, refusing embassies from foreign countries and firing on ships near its shores. At the start of the war, Japan had the benefit of three decades of reform, leaving Korea backward and vulnerable.

Conflict over Korea

As a newly risen power, Japan turned its attention toward its neighbor, Korea. Japan wanted to block any other power from annexing or dominating Korea, resolving to end the centuries-old Chinese suzerainty. As Prussian advisor Major Klemens Meckel put it to the Japanese, Korea was "a dagger pointed at the heart of Japan".[4] Moreover, Japan realized the potential economic benefits of Korea's coal and iron ore deposits for Japan's growing industrial base, and of Korea's agricultural exports to feed the growing Japanese population.

On February 27, 1876, after several confrontations between Korean isolationists and Japanese, Japan imposed the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1876, forcing Korea open to Japanese trade. Similar treaties were signed between Korea and other nations.

Korea had traditionally been a tributary state of China's Qing Empire, which exerted large influence over the conservative Korean officials gathered around the royal family of the Joseon kingdom. Opinion in Korea itself was split: conservatives wanted to retain the traditional relationship under China, while reformists wanted to approach Japan and Western nations. After fighting two Opium Wars against the British in 1839 and 1856, and another war against the French in 1885, China was unable to resist the encroachment of Western powers (see Unequal Treaties). Japan saw the opportunity to take China's place in the strategically vital Korea.

1882 crisis

In 1882, the Korean peninsula experienced a severe drought which led to food shortages, causing much hardship and discord among the population. Korea was on the verge of bankruptcy, even falling months behind on military pay, causing deep resentment among the soldiers. On July 23, a military mutiny and riot broke out in Seoul in which troops, assisted by the population, sacked the rice granaries. The next morning, the crowd attacked the royal palace and barracks, and then the Japanese legation. The Japanese legation staff managed to escape to Chemulpo and then Nagasaki via the British survey ship HMS Flying Fish.

In response, Japan sent four warships and a battalion of troops to Seoul to safeguard Japanese interests and demand reparations. The Chinese then deployed 4,500 troops to counter the Japanese. However, tensions subsided with the Treaty of Chemulpo, signed on the evening of August 30, 1882. The agreement specified that the Korean conspirators would be punished and 50,000 yen would be paid to the families of slain Japanese. The Japanese government would also receive 500,000 yen, a formal apology, and permission to station troops at their diplomatic legation in Seoul.

Gapsin Coup

In 1884, a group of pro-Japanese reformers briefly overthrew the pro-Chinese conservative Korean government in a bloody coup d'état. However, the pro-Chinese faction, with assistance from Qing forces led by the general Yuan Shikai, succeeded in regaining control in an equally bloody counter-coup. These coups resulted not only in the deaths of a number of reformers, but also in the burning of the Japanese legation and the deaths of several legation guards and citizens. This caused a crisis between Japan and China, which was eventually settled by the Sino-Japanese Convention of Tientsin of 1885, in which the two sides agreed to pull their expeditionary forces out of Korea simultaneously, not send military trainers to the Korean military, and give warning to the other side should one decide to send troops to Korea. Chinese and Japanese troops then left, and diplomatic relations were restored between Japan and Korea.

However, the Japanese were frustrated by repeated Chinese attempts to undermine their influence in Korea. Yuan Shikai remained set as "Chinese Resident", in what the Chinese intended as a sort of viceroy role directing Korean affairs. He attempted to encourage Chinese and hinder Japanese trade, though Japan remained Korea's largest trading partner, and his government provided Korea with loans. The Chinese built telegraphs linking Korea to the Chinese network.

Nagasaki incident

The Nagasaki incident was a riot that took place in the Japanese port city of Nagasaki in 1886. Four warships from the Qing Empire's navy, the Beiyang Fleet, stopped at Nagasaki, apparently to carry out repairs. Some Chinese sailors caused trouble in the city and started the riot. Several Japanese policemen confronting the rioters were killed. The Qing government did not apologize after the incident, which resulted in a wave of anti-Qing sentiment in Japan.

Bean controversy

A poor harvest in 1889 caused a governor of Korea's Hamgyong Province to prohibit soybean exports to Japan. Japan requested and received compensation in 1893 for their importers. The incident highlighted the growing dependence Japan felt on Korean food imports.[5]

Kim Ok-gyun affair

On March 28, 1894, a pro-Japanese Korean revolutionary, Kim Ok-gyun, was assassinated in Shanghai. Kim had fled to Japan after his involvement in the 1884 coup and the Japanese had turned down Korean demands that he be extradited. Ultimately, he was lured to Shanghai, where he was killed by a Korean, Hong Jong-u, at a Japanese inn in the international settlement. His body was then taken aboard a Chinese warship and sent back to Korea, where it was quartered and displayed as a warning to other rebels. The Japanese government took this as an outrageous affront.[6]

Donghak Rebellion

Tension ran high between China and Japan by June 1894 but war was not yet inevitable. On June 4, the Korean king, Gojong, requested aid from the Qing government in suppressing the Donghak Rebellion. Although the rebellion was not as serious as it initially seemed and hence Qing reinforcements were not necessary, the Qing government still sent the general Yuan Shikai as its plenipotentiary to lead 28,000 troops to Korea. According to the Japanese, the Qing government had violated the Convention of Tientsin by not informing the Japanese government of its decision to send troops, but the Qing claimed that Japan had approved this.[7] The Japanese countered by sending a 8,000-troops expeditionary force (the Oshima Composite Brigade) to Korea. The first 400 troops arrived on June 9 en route to Seoul, and 3,000 landed at Inchon on June 12.[8]

However, Japanese officials denied any intention to intervene. As a result, the Qing viceroy Li Hongzhang "was lured into believing that Japan would not wage war, but the Japanese were fully prepared to act."[9] The Qing government turned down Japan's suggestion for Japan and China to cooperate to reform the Korean government. When Korea demanded that Japan withdraw its troops from Korea, the Japanese refused.

In early June 1894, the 8,000 troops captured the Korean king Gojong, occupied the Royal Palace in Seoul and, by June 25, replaced the existing Korean government with members of the pro-Japanese faction.[8] Even though Qing forces were already leaving Korea after finding themselves unneeded there, the new pro-Japanese Korean government granted Japan the right to expel Qing forces while Japan dispatched more troops to Korea. The Qing Empire rejected the new Korean government as illegitimate.

Status of combatants

Japan

Japan's reforms under the Meiji Emperor gave significant priority to the creation of an effective modern national army and navy, especially naval construction. Japan sent numerous military officials abroad for training and evaluation of the relative strengths and tactics of Western armies and navies.

Imperial Japanese Navy

| Major Combatants |

|---|

| Protected Cruisers |

| Matsushima (flagship) |

| Itsukushima |

| Hashidate |

| Naniwa |

| Takachiho |

| Yaeyama |

| Akitsushima |

| Yoshino |

| Izumi |

| Cruisers |

| Chiyoda |

| Armored Corvettes |

| Hiei |

| Kongō |

| Ironclad Warship |

| Fusō |

.jpg)

The Imperial Japanese Navy was modeled after the British Royal Navy,[10] at the time the foremost naval power. British advisors were sent to Japan to train the naval establishment, while Japanese students were in turn sent to Britain to study and observe the Royal Navy. Through drilling and tuition by Royal Navy instructors, Japan developed naval officers expert in the arts of gunnery and seamanship.[11]

At the start of hostilities, the Imperial Japanese Navy comprised a fleet of 12 modern warships, (Izumi being added during the war), the frigate Takao, 22 torpedo boats, and numerous auxiliary/armed merchant cruisers and converted liners.

Japan did not yet have the resources to acquire battleships and so planned to employ the Jeune École doctrine which favoured small, fast warships, especially cruisers and torpedo boats, with guns powerful enough to destroy larger craft.

Many of Japan's major warships were built in British and French shipyards (eight British, three French and two Japanese-built) and 16 of the torpedo boats were known to have been built in France and assembled in Japan.

Imperial Japanese Army

The Meiji government at first modeled their army after the French Army. French advisers had been sent to Japan with two military missions (in 1872–1880 and 1884), in addition to one mission under the shogunate. Nationwide conscription was enforced in 1873 and a Western-style conscript army was established; military schools and arsenals were also built.

In 1886, Japan turned toward the German-Prussian model as the basis for its army, adopting German doctrines, military system and organisation. In 1885 Klemens Meckel, a German adviser, implemented new measures, such as the reorganization of the command structure into divisions and regiments; the strengthening of army logistics, transportation, and structures (thereby increasing mobility); and the establishment of artillery and engineering regiments as independent commands.

By the 1890s, Japan had at its disposal a modern, professionally trained Western-style army which was relatively well equipped and supplied. Its officers had studied in Europe and were well educated in the latest tactics and strategy. By the start of the war, the Imperial Japanese Army could field a total force of 120,000 men in two armies and five divisions.

| Imperial Japanese Army composition 1894–1895 |

| 1st Japanese Army |

|---|

| 3rd Provincial Division (Nagoya) |

| 5th Provincial Division (Hiroshima) |

| 2nd Japanese Army |

| 1st Provincial Division (Tokyo) |

| 2nd Provincial Division (Sendai) |

| 6th Provincial Division (Kumamoto) |

| In reserve |

| 4th Provincial Division (Osaka) |

| Invasion of Formosa (Taiwan) |

| Imperial Guards Division |

China

The Beiyang Army and Beiyang Fleet were the best equipped and most modernized Chinese military, but suffered from corruption. Military leaders and officials systematically embezzled funds, even during the war. As a result, the Beiyang Fleet did not purchase any battleships after its establishment in 1888. The purchase of ammunition stopped in 1891, with the funding diverted to renovate the Summer Palace in Beijing. Logistics were lacking, as construction of railroads in Manchuria had been discouraged. The Qing Empire's military morale was generally very low due to lack of pay, low prestige, use of opium, and the poor leadership which had contributed to defeats such as the abandonment of the very well-fortified and defensible Weihaiwei.

Beiyang Army

The Qing Empire did not have a national army. Following the Taiping Rebellion, the Qing army had been segregated into separate forces based on ethnicity (Manchu, Han Chinese, Mongol, Hui (Muslim), etc.)[12] and further divided into largely independent regional commands. The war was mainly fought by the Beiyang Fleet and Beiyang Army, whose soldiers were mainly from the former Huai Army raised to suppress the Taiping rebels. The Qing government's pleas for help from other regional armies and navies were ignored due to rivalry among the different regional commands.

Beiyang Fleet

The Beiyang Fleet was one of the four modernised Chinese navies in the late Qing dynasty. The navies were heavily sponsored by Li Hongzhang, the Viceroy of Zhili. The Beiyang Fleet was the dominant navy in East Asia before the first Sino-Japanese War. However, ships were not maintained properly and indiscipline was common.[13] Sentries spent their time gambling, watertight doors were left open, rubbish was dumped in gun barrels and gunpowder for explosive shells was sold and replaced with cocoa. At the Yalu River, a battleship had one of its guns pawned by the admiral Ding Ruchang.[14]

| Beiyang Fleet |

Major combatants |

|---|---|

| Ironclad battleships | Dingyuan (flagship), Zhenyuan |

| Armoured cruisers | King Yuen, Lai Yuen |

| Protected cruisers | Chih Yuen, Ching Yuen |

| Cruisers | Torpedo Cruisers – Tsi Yuen, Kuang Ping/Kwang Ping | Chaoyong, Yangwei |

| Coastal warship | Pingyuan |

| Corvette | Kwan Chia |

13 or so torpedo boats, numerous Gunboats and chartered merchant vessels

Foreign opinions of Chinese and Japanese forces

The prevailing view in the West was that the modernized Chinese forces would crush the Japanese. Observers commended Chinese units such as the Huai Army and Beiyang Fleet.[15]

The German General Staff predicted Japanese defeat. William Lang, a British advisor to the Chinese military, praised Chinese training, ships, guns, and fortifications, stating that "in the end, there is no doubt that Japan must be utterly crushed".[16]

Contemporaneous wars fought by the Qing Empire

While the Qing Empire was fighting the First Sino-Japanese War, it was also simultaneously engaging rebels in the Dungan Revolt in northwestern China, where thousands lost their lives. The generals Dong Fuxiang, Ma Anliang and Ma Haiyan were initially summoned by the Qing government to bring the Hui troops under their command to participate in the First Sino-Japanese War, but they were eventually sent to suppress the Dungan Revolt instead.[17]

Early stages of the war

1 June 1894 : The Donghak Rebel Army moves toward Seoul. The Korean government requests help from the Qing government to suppress the revolt.

6 June 1894: Approximately 2,465 Chinese soldiers are transported to Korea to suppress the Donghak Rebellion. Japan asserts that it was not notified and thus China has violated the Convention of Tientsin, which requires that China and Japan must notify each other before intervening in Korea. China asserts that Japan was notified and approved of Chinese intervention.

8 June 1894: First of approximately 4,000 Japanese soldiers and 500 marines land at Jemulpo (Incheon).

11 June 1894: End of the Donghak Rebellion.

13 June 1894: The Japanese government telegraphs the commander of the Japanese forces in Korea, Ōtori Keisuke, to remain in Korea for as long as possible despite the end of the rebellion.

16 June 1894: Japanese Foreign Minister Mutsu Munemitsu meets with Wang Fengzao, the Qing ambassador to Japan, to discuss the future status of Korea. Wang states that the Qing government intends to pull out of Korea after the rebellion has been suppressed and expects Japan to do the same. However, China retains a resident to look after Chinese primacy in Korea.

22 June 1894: Additional Japanese troops arrive in Korea. Japanese Prime Minister Itō Hirobumi tells Matsukata Masayoshi that since the Qing Empire appear to be making military preparations, there is probably "no policy but to go to war." Mutsu tells Ōtori to press the Korean government on the Japanese demands.

26 June 1894: Ōtori presents a set of reform proposals to the Korean king Gojong. Gojong's government rejects and in return insists on troop withdrawals.

7 July 1894: Failure of mediation between China and Japan arranged by the British ambassador to China.

19 July 1894: Establishment of the Japanese Combined Fleet, consisting of almost all vessels in the Imperial Japanese Navy. Mutsu cables Ōtori to take any necessary steps to compel the Korean government to carry out a reform program.

23 July 1894: Japanese troops occupy Seoul, capture Gojong, and establish a new pro-Japanese government, which terminates all Sino-Korean treaties and grants the Imperial Japanese Army the right to expel the Qing Empire's Beiyang Army from Korea.

25 July 1894: First battle of the war: Battle of Pungdo / Hoto-oki kaisen

Events during the war

Opening moves

By July 1894, Qing forces in Korea numbered 3000–3500 and were outnumbered by Japan. They could only be supplied by sea through Asan Bay. The Japanese objective was first to blockade the Chinese at Asan (south of Seoul, South Korea) and then encircle them with their land forces.

Sinking of the Kow-shing

On 25 July 1894, the cruisers Yoshino, Naniwa and Akitsushima of the Japanese flying squadron, which had been patrolling off Asan Bay, encountered the Chinese cruiser Tsi-yuan and gunboat Kwang-yi.[18] These vessels had steamed out of Asan to meet the transport Kow-shing, escorted by the Chinese gunboat Tsao-kiang. After an hour-long engagement, the Tsi-yuan escaped while the Kwang-yi grounded on rocks, where its powder-magazine exploded.

The Kow-shing was a 2,134-ton British merchant vessel owned by the Indochina Steam Navigation Company of London, commanded by Captain T. R. Galsworthy and crewed by 64 men. The ship was chartered by the Qing government to ferry troops to Korea, and was on her way to reinforce Asan with 1,100 troops plus supplies and equipment. A German artillery officer, Major von Hanneken, advisor to the Chinese, was also aboard. The ship was due to arrive on 25 July.

The cruiser Naniwa, under Captain Tōgō Heihachirō, intercepted the Kow-shing and captured its escort. The Japanese then ordered the Kow-shing to follow Naniwa and directed that Europeans be transferred to Naniwa. However the 1,100 Chinese on board, desperate to return to Taku, threatened to kill the English captain, Galsworthy, and his crew. After four hours of negotiations, Captain Togo gave the order to fire upon the vessel. A torpedo missed, but a subsequent broadside hit the Kow Shing, which started to sink.

In the confusion, some of the Europeans escaped overboard, only to be fired upon by the Chinese. The Japanese rescued three of the British crew (the captain, first officer and quartermaster) and 50 Chinese, and took them to Japan. The sinking of the Kow-shing almost caused a diplomatic incident between Japan and Great Britain, but the action was ruled in conformity with international law regarding the treatment of mutineers (the Chinese troops).

The German gunboat Iltis rescued 150 Chinese, the French gunboat Le Lion rescued 43, and the British cruiser HMS Porpoise rescued an unknown number.[19]

Conflict in Korea

Commissioned by the new pro-Japanese Korean government to forcibly expel Chinese forces, Major-General Ōshima Yoshimasa led mixed Japanese brigades numbering about 4,000 on a rapid forced march from Seoul south toward Asan Bay to face 3,500 Chinese troops garrisoned at Seonghwan Station east of Asan and Kongju.

On 28 July 1894, the two forces met just outside Asan in an engagement that lasted till 0730 hours the next morning. The Chinese gradually lost ground to the superior Japanese numbers, and finally broke and fled towards Pyongyang. Chinese casualties amounted to 500 killed and wounded, compared to 82 Japanese casualties.

On 1 August, war was officially declared between China and Japan.

By 4 August, the remaining Chinese forces in Korea retreated to the northern city of Pyongyang, where they were met by troops sent from China. The 13,000–15,000 defenders made defensive repairs to the city, hoping to check the Japanese advance.

On 15 September, the Imperial Japanese Army converged on the city of Pyongyang from several directions. The Japanese assaulted the city and eventually defeated the Chinese by an attack from the rear; the defenders surrendered. Taking advantage of heavy rainfall overnight, the remaining Chinese troops escaped Pyongyang and headed northeast toward the coastal city of Uiju. Casualties were 2,000 killed and around 4,000 wounded for the Chinese, while the Japanese casualties totaled 102 men killed, 433 wounded, and 33 missing. In the early morning of 16 September, the entire Japanese army entered Pyongyang.

Qing Hui Muslim General Zuo Baogui (左寶貴) (1837–94), from Shandong province, died in action in Pyongyang, Korea from Japanese artillery in 1894 while securing the city. A memorial to him was constructed.[20]

Defeat of the Beiyang fleet

On September 17, 1894, Japanese warships encountered the larger Chinese Beiyang Fleet off the mouth of the Yalu River. The Imperial Japanese Navy destroyed eight out of the ten Chinese warships, assuring Japan's command of the Yellow Sea. The Chinese were able to land 4,500 troops near the Yalu River.

The Battle of the Yalu River was the largest naval engagement of the war and was a major propaganda victory for Japan.[21]

Invasion of Manchuria

With the defeat at Pyongyang, the Chinese abandoned northern Korea and instead took up defensive positions in fortifications along their side of the Yalu River near Jiuliancheng. After receiving reinforcements by 10 October, the Japanese quickly pushed north toward Manchuria.

On the night of 24 October 1894, the Japanese successfully crossed the Yalu River, undetected, by erecting a pontoon bridge. The following afternoon of 25 October at 1700 hours, they assaulted the outpost of Hushan, east of Jiuliancheng. At 2030 hours the defenders deserted their positions and by the next day they were in full retreat from Jiuliancheng.

With the capture of Jiuliancheng, General Yamagata's 1st Army Corps occupied the nearby city of Dandong, while to the north, elements of the retreating Beiyang Army set fire to the city of Fengcheng. The Japanese had established a firm foothold on Chinese territory with the loss of only four killed and 140 wounded.

The Japanese 1st Army Corps then split into two groups with General Nozu Michitsura's 5th Provincial Division advancing toward the city of Mukden (present-day Shenyang) and Lieutenant-General Katsura Tarō's 3rd Provincial Division pursuing fleeing Chinese forces west along toward the Liaodong Peninsula.

By December, the 3rd Provincial Division had captured the towns of Tatungkau, Takushan, Xiuyan, Tomucheng, Haicheng and Kangwaseh. The 5th Provincial Division marched during a severe Manchurian winter towards Mukden.

The Japanese 2nd Army Corps under Ōyama Iwao landed on the south coast of Liaodong Peninsula on 24 October and quickly moved to capture Jinzhou and Dalian Bay on 6–7 November. The Japanese laid siege to the strategic port of Lüshunkou (Port Arthur).

Fall of Lüshunkou

By 21 November 1894, the Japanese had taken the city of Lüshunkou (Port Arthur). Furious over the Chinese massacre, torture and mutilation of captured wounded Japanese soldiers, the Japanese army massacred thousands of the city's civilian Chinese inhabitants in an event that came to be called the Port Arthur Massacre (although the scale and nature of the killing continues to be debated).

By 10 December 1894, Kaipeng (present-day Gaizhou) fell to the Japanese 1st Army Corps.

Fall of Weihaiwei

The Chinese fleet subsequently retreated behind the Weihaiwei fortifications. However, they were then surprised by Japanese ground forces, who outflanked the harbor's defenses in coordination with the navy.[22] The Battle of Weihaiwei would be a 23-day siege with the major land and naval components taking place between 20 January and 12 February 1895.

After Weihaiwei's fall on 12 February 1895, and an easing of harsh winter conditions, Japanese troops pressed further into southern Manchuria and northern China. By March 1895 the Japanese had fortified posts that commanded the sea approaches to Beijing. This would be the last major battle to be fought; numerous skirmishes would follow. The Battle of Yinkou was fought outside the port town of Yingkou, Manchuria, on 5 March 1895.

Occupation of the Pescadores Islands

On 23 March 1895, Japanese forces attacked the Pescadores Islands, off the west coast of Taiwan. In a brief and almost bloodless campaign, the Japanese defeated the islands' Chinese garrison and occupied the main town of Magong. This operation effectively prevented Chinese forces in Taiwan from being reinforced, and allowed the Japanese to press their demand for the cession of Taiwan in the negotiations leading to the conclusion of the Treaty of Shimonoseki in April 1895.

End of the war

The Treaty of Shimonoseki was signed on 17 April 1895. The Qing Empire recognized the total independence of Korea and ceded the Liaodong Peninsula, Taiwan and Penghu Islands to Japan "in perpetuity". The disputed islands known as "Senkaku/Diaoyu" islands were not named by this treaty, but Japan annexed these uninhabited islands to Okinawa Prefecture in 1895. Japan asserts this move was taken independently of the treaty ending the war, and China asserts that they were implied as part of the cession of Taiwan.

Additionally, the Qing Empire was to pay Japan 200 million taels of silver as war reparations. The Qing government also signed a commercial treaty permitting Japanese ships to operate on the Yangtze River, to operate manufacturing factories in treaty ports and to open four more ports to foreign trade. The Triple Intervention, however, forced Japan to give up the Liaodong Peninsula in exchange for another 30 million taels of silver (equivalent to about 450 million yen).

After the war, according to the Chinese scholar, Jin Xide, the Qing government paid a total of 340,000,000 taels (13,600 tons) of silver to Japan in both war reparations and trophies. This was equivalent to about 510,000,000 Japanese yen at the time, about 6.4 times the Japanese government's revenue.

Japanese invasion of Taiwan

"The cession of the island to Japan was received with such disfavour by the Chinese inhabitants that a large military force was required to effect its occupation. For nearly two years afterwards, a bitter guerrilla resistance was offered to the Japanese troops, and large forces — over 100,000 men, it was stated at the time — were required for its suppression. This was not accomplished without much cruelty on the part of the conquerors, who, in their march through the island, perpetrated all the worst excesses of war. They had, undoubtedly, considerable provocation. They were constantly attacked by ambushed enemies, and their losses from battle and disease far exceeded the entire loss of the whole Japanese army throughout the Manchurian campaign. But their revenge was often taken on innocent villagers. Men, women, and children were ruthlessly slaughtered or became the victims of unrestrained lust and rapine. The result was to drive from their homes thousands of industrious and peaceful peasants, who, long after the main resistance had been completely crushed, continued to wage a vendetta war, and to generate feelings of hatred which the succeeding years of conciliation and good government have not wholly eradicated." - The Cambridge Modern History, Volume 12[23]

Several Qing officials in Taiwan resolved to resist the cession of Taiwan to Japan under the Treaty of Shimonoseki, and on 23 May declared the island to be an independent Republic of Formosa. On 29 May, Japanese forces under Admiral Motonori Kabayama landed in northern Taiwan, and in a five-month campaign defeated the Republican forces and occupied the island's main towns. The campaign effectively ended on 21 October 1895, with the flight of Liu Yongfu, the second Republican president, and the surrender of the Republican capital Tainan.

Aftermath

The Japanese success during the war was the result of the modernisation and industrialisation embarked upon two decades earlier.[24] The war demonstrated the superiority of Japanese tactics and training from the adoption of a Western-style military.

The Imperial Japanese Army and Imperial Japanese Navy were able to inflict a string of defeats on the Chinese through foresight, endurance, strategy and power of organisations. Japanese prestige rose in the eyes of the world. The victory established Japan as the dominant power in Asia.[25][26]

For China, the war revealed how ineffective and corrupt were its government and policies and the Qing administration. Traditionally, China viewed Japan as a subordinate part of the Chinese cultural sphere. Although China had been defeated by European powers in the 19th century, defeat at the hands of an Asian power and a former tributary state was a bitter psychological blow. Anti-foreign sentiment and agitation grew, which would later culminate in the form of the Boxer Rebellion five years later. The Manchu population was devastated by the fighting during the First Sino-Japanese War and the Boxer Rebellion, with massive casualties sustained during the wars and subsequently being driven into extreme suffering and hardship in Beijing and northeast China.[27]

Although Japan had achieved what it had set out to accomplish and ended Chinese influence over Korea, Japan had been forced to relinquish the Liaodong Peninsula, (Port Arthur), in exchange for an increased financial indemnity. The European powers (especially Russia) had no objection to the other clauses of the treaty but felt that Japan should not gain Port Arthur, for they had their own ambitions in that part of the world. Russia persuaded Germany and France to join in applying diplomatic pressure on Japan, resulting in the Triple Intervention of 23 April 1895.

Japan succeeded in eliminating Chinese influence over Korea, but it was Russia who reaped the benefits. Korea proclaimed itself the Korean Empire and announced its independence from the Qing Empire. The Japanese sponsored Gabo reforms (Kabo reforms) from 1894-1896 transformed Korea: legal slavery was abolished in all forms; the yangban class lost all special privileges; outcastes were abolished; equality of law; equality of opportunity in the face of social background; child marriage was abolished, Hangul was to be used in government documents; Korean history was introduced in schools; the Chinese calendar was replaced with the Gregorian calendar (Common Era); education was expanded and new textbooks written.[8]

In 1895, a pro-Russian official tried to remove the king of Korea to the Russian legation and failed, but a second attempt succeeded. Thus, for a year, the King reigned from the Russian legation in Seoul. The concession to build a Seoul-Inchon railway had been granted to Japan in 1894 was revoked and granted to Russia. Russian guards guarded the king in his palace even after he left the Russian legation.

China's defeat precipitated an increase in railway construction in the country, as foreign powers demanded China to make railway concessions.[28][29]

In 1898, Russia signed a 25-year lease on the Liaodong Peninsula and proceeded to set up a naval station at Port Arthur. Although that infuriated the Japanese, the latter were more concerned with the Russian encroachment in Korea than that in Manchuria. Other powers, such as France, Germany and Britain, took advantage of the situation in China and gained land, port, and trade concessions at the expense of the decaying Qing Empire. Qingdao and Jiaozhou was acquired by Germany, Guangzhouwan by France, and Weihaiwei and the New Territories by Britain.

Tensions between Russia and Japan would increase in the years after the First Sino-Japanese War. During the Boxer Rebellion, an eight-member international force was sent to suppress and quell the uprising; Russia sent troops into Manchuria as part of this force. After the suppression of the Boxers, the Russian government agreed to vacate the area. However, by 1903, it had actually increased the size of its forces in Manchuria.

Negotiations between the two nations (1901–1904) to establish mutual recognition of respective spheres of influence (Russia over Manchuria and Japan over Korea) were repeatedly and intentionally stalled by the Russians. They felt that they were strong and confident enough not to accept any compromise and believed Japan would not go to war against a European power. Russia also had intentions to use Manchuria as a springboard for further expansion of its interests in the Far East. In 1903, Russian soldiers began construction of a fort at Yongnampo but stopped at Japanese protests.[8]

In 1902, Japan formed an alliance with Britain, the terms of which stated that if Japan went to war in the Far East and that a third power entered the fight against Japan, then Britain would come to the aid of the Japanese.[30] This was a check to prevent Germany or France from intervening militarily in any future war with Russia. Japan sought to prevent a repetition of the Triple Intervention that deprived her of Port Arthur. The British reasons for joining the alliance were to check the spread of Russian expansion into the Pacific area;[30] to strengthen Britain's hand to focus on other areas and to gain a powerful naval ally in the Pacific.

Increasing tensions between Japan and Russia were a result of Russia's unwillingness compromise and the prospect of Korea falling under Russia's domination, therefore coming into conflict with and undermining Japan's interests. Eventually, Japan was forced to take action. This would be the deciding factor and catalyst that would lead to the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05.

In popular culture

The events of the First Sino-Japanese War are depicted or fictionalised in films and television series such as Mga Bakas ng Dugo sa Kapirasong Lupa, Empress Myeongseong (2001), The Sword with No Name (2009), Saka no Ue no Kumo (2009), The Sino-Japanese War at Sea 1894 (2012).

See also

- History of China

- History of Japan

- History of Korea

- History of Taiwan

- Military history of China

- Military history of Japan

- Second Sino-Japanese War

- Russo-Japanese War

- Sino-Japanese relations

References

Citations

- ↑ "Japan Anxious for a Fight; The Chinese Are Slow and Not in Good Shape to Go to War," New York Times. July 30, 1894.

- ↑ Jansen 2002, p. 335.

- ↑ www.ocu.mit.edu

- ↑ Duus, P. (1976). The rise of modern Japan (p. 125). Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- ↑ Seth, p. 445

- ↑ Jansen 2002, p. 431.

- ↑ James McClain, "Japan a Modern History," 297

- 1 2 3 4 Seth, Michael J (2010). A History of Korea: From Antiquity to the Present. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 225. ISBN 978-0742567160.

- ↑ John King Fairbank and Kwang-Ching Liu, ed. The Cambridge History of China: Late Ch'ing, 1800-1911. Volume 11, Part 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980),105.

- ↑ Evans & Peattie 1997, p. 12.

- ↑ "The skills of the Japanese officers and men was [sic] astronomically higher those of their Chinese counterparts."

- ↑ Michael Dillon (1999). China's Muslim Hui community: Migration, settlement and sects. Richmond: Curzon Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-7007-1026-3. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Sondhaus 2001, pp. 169-170.

- ↑ Geoffrey Regan, Naval Blunders, page 28

- ↑ John King Fairbank, Kwang-Ching Liu, Denis Crispin Twitchett, ed. (1980). Late Ch'ing, 1800-1911. Volume 11, Part 2 of The Cambridge History of China Series (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 268. ISBN 0-521-22029-7. Retrieved 2012-01-18.

On the eve of the Sino-Japanese War, China appeared, to undiscerning observers, to possess respectable military and naval forces. Praise for Li Hung-chang's Anhwei Army and other Chinese forces was not uncommon, and the Peiyang Navy elicited considerable favourable comment.179 When war between China and Japan appeared likely, most Westerners thought China had the advantage. Her army was vast, and her navy both out-

- ↑ John King Fairbank, Kwang-Ching Liu, Denis Crispin Twitchett, ed. (1980). Late Ch'ing, 1800-1911. Volume 11, Part 2 of The Cambridge History of China Series (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 269. ISBN 0-521-22029-7. Retrieved 2012-01-18.

numbered and outweight Japan's. The German general staff considered a Japanese victory improbable. In an interview with Reuters, William Lang predicted defeat for Japan. Lang thought that the Chinese navy was well-drilled, the ships were fit, the artillery was at least adequate, and the coastal forts were strong. Weihaiwei, he said, was impregnable. Although Lang emphasized that everything depended on how China's forces were led, he had faith that 'in the end, there is no doubt that Japan must be utterly crushed'.180

- ↑ 董福祥与西北马家军阀的的故事 - 360Doc个人图书馆

- ↑ Evans & Peattie 1997, p. 41.

- ↑ Sequence of events, and numbers of rescued and dead, taken from several articles from The Times of London from 2 August 1894-25 October 1894

- ↑ Aliya Ma Lynn (2007). Muslims in China. Volume 3 of Asian Studies. University Press. p. 44. ISBN 0-88093-861-7. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Paine 2003, pp. 179-189.

- ↑ Evans & Peattie 1997, p. 46.

- ↑ Sir Adolphus William Ward; George Walter Prothero; Sir Stanley Mordaunt Leathes; Ernest Alfred Benians (1910). The Cambridge Modern History. Macmillan. pp. 573–.

- ↑ Schencking 2005, p. 78.

- ↑ Paine 2003, pp. 293.

- ↑ "A new balance of power had emerged. China's millennia-long regional dominance had abruptly ended. Japan had become the dominant power of Asia, a position it would retain throughout the twentieth century". Paine, The Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895: Perception, Power, and Primacy.

- ↑ Rhoads, Edward J. M. (2011). Manchus and Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861–1928. University of Washington Press. p. 80. ISBN 0295804122. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ↑ Davis, Clarence B.; Wilburn, Kenneth E., Jr; Robinson, Ronald E. (1991). "Railway Imperialism in China, 1895–1939". Railway Imperialism. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 159. ISBN 9780313259661. Retrieved 10 August 2015 – via Questia. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Rousseau, Jean-François (June 2014). "An Imperial Railway Failure: The Indochina-Yunnan Railway, 1898-1941". Journal of Transport History 35 (1). Retrieved 10 August 2015 – via Questia. (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 Evans & Peattie 1997, p. 65.

Sources

-

This article incorporates text from The living age ..., Volume 226, by Eliakim Littell, Robert S. Littell, Making of America Project, a publication from 1900 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The living age ..., Volume 226, by Eliakim Littell, Robert S. Littell, Making of America Project, a publication from 1900 now in the public domain in the United States. -

This article incorporates text from Eclectic magazine: foreign literature, by John Holmes Agnew, Walter Hilliard Bidwell, a publication from 1900 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Eclectic magazine: foreign literature, by John Holmes Agnew, Walter Hilliard Bidwell, a publication from 1900 now in the public domain in the United States. - Duus, Peter (1998). The Abacus and the Sword: The Japanese Penetration of Korea. University of California Press. ISBN 0-52092-090-2.

- Schencking, J. Charles (2005). Making Waves: Politics, Propaganda, And The Emergence Of The Imperial Japanese Navy, 1868-1922. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4977-9.

- Evans, David C; Peattie, Mark R (1997). Kaigun: strategy, tactics, and technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-192-7.

- Jansen, Marius B. (2002). The Making of Modern Japan. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-6740-0334-9.

- Jansen, Marius B. (1995). The Emergence of Meiji Japan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-5214-8405-7.

- Paine, S.C.M (2002). The Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895: Perceptions, Power, and Primacy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-81714-5.

- Palais, James B. (1975). Politics and Policy in Traditional Korea. Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 0-67468-770-1.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (2001). Naval Warfare, 1815–1914. Routledge. ISBN 0-41521-477-7.

Further reading

- Chamberlin, William Henry. Japan Over Asia, 1937, Little, Brown, and Company, Boston.

- Colliers (Ed.), The Russo-Japanese War, 1904, P.F. Collier & Son, New York.

- Kodansha Japan An Illustrated Encyclopedia, 1993, Kodansha Press, Tokyo ISBN 4-06-205938-X

- Lone, Stewart. Japan's First Modern War: Army and Society in the Conflict with China, 1894–1895, 1994, St. Martin's Press, New York.

- Mutsu, Munemitsu. (1982). Kenkenroku (trans. Gordon Mark Berger). Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press. ISBN 9780860083061; OCLC 252084846

- Paine, S.C.M. The Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895: Perception, Power, and Primacy, 2003, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, MA, 412 pp.

- Sedwick, F.R. (R.F.A.). The Russo-Japanese War, 1909, The Macmillan Company, NY, 192 pp.

- Theiss, Frank. The Voyage of Forgotten Men, 1937, Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1st Ed., Indianapolis & New York.

- Warner, Dennis and Peggy. The Tide At Sunrise, 1974, Charterhouse, New York.

- Urdang, Laurence/Flexner, Stuart, Berg. The Random House Dictionary of the English Language, College Edition. Random House, New York, (1969).

- Military Heritage did an editorial on the Sino-Japanese War of 1894 (Brooke C. Stoddard, Military Heritage, December 2001, Volume 3, No. 3).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to First Sino-Japanese War. |

- 程映虹︰從"版畫事件"到《中國向西行進》Peter Perdue 濮德培和中國當代民族主義 (Chinese)

- Detailed account of the naval Battle of the Yalu River by Philo Norton McGiffen

- Under the Dragon Flag — My Experiences in the Chino-Japanese War by James Allan' at Project Gutenberg

- Print exhibition at MIT

- The Sinking of the Kowshing – Captain Galsworthy's Report

- SinoJapaneseWar.com A detailed account of the Sino-Japanese War

- The Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895: as seen in prints and archives (British Library/Japan Center for Asian Historical Records)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|