Firmicutes

| Firmicutes | |

|---|---|

| |

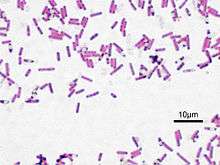

| Bacillus subtilis, Gram stained | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Firmicutes |

| Classes | |

The Firmicutes (Latin: firmus, strong, and cutis, skin, referring to the cell wall) are a phylum of bacteria, most of which have Gram-positive cell wall structure.[1] A few, however, such as Megasphaera, Pectinatus, Selenomonas and Zymophilus, have a porous pseudo-outer-membrane that causes them to stain Gram-negative. Scientists once classified the Firmicutes to include all Gram-positive bacteria, but have recently defined them to be of a core group of related forms called the low-G+C group, in contrast to the Actinobacteria. They have round cells, called cocci (singular coccus), or rod-like forms (bacillus).

Many Firmicutes produce endospores, which are resistant to desiccation and can survive extreme conditions. They are found in various environments, and the group includes some notable pathogens. Those in one family, the heliobacteria, produce energy through photosynthesis. Firmicutes play an important role in beer, wine, and cider spoilage.

Classes

The group is typically divided into the Clostridia, which are anaerobic, the Bacilli, which are obligate or facultative aerobes, and the Mollicutes.

On phylogenetic trees, the first two groups show up as paraphyletic or polyphyletic, as do their main genera, Clostridium and Bacillus.[2]

Phylogeny

The currently accepted taxonomy is based on the List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN) [3] and National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)[4] and the phylogeny is based on 16S rRNA-based LTP release 111 by The All-Species Living Tree Project [5]

| |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

Notes:

♠ Strains found at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) but not listed in the List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature LPSN

Genera

While there are currently more than 274 genera within the Firmicutes phylum, notable genera of Firmicutes include:

Bacilli, order Bacillales

Bacilli, order Lactobacillales

- Acetobacterium

- Clostridium

- Eubacterium

- Heliobacterium

- Heliospirillum

- Megasphaera

- Pectinatus

- Selenomonas

- Zymophilus

- Sporohalobacter

- Sporomusa

Erysipelotrichi

Health implications

Firmicutes make up the largest portion of the mouse and human gut microbiome.[6] The division Firmicutes as part of the gut flora has been shown to be involved in energy resorption and obesity.[7][8][9]

Laboratory detection

It was once impossible to categorically define a given bacterium as belonging to Firmicutes, as the phylum is highly diverse in phenotypic characteristics due to its members' promiscuous plasmid exchange across species and genera, but the presence of Firmicutes can now be detected by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques.[10]

References

- ↑ "Firmicutes" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ↑ Wolf M, Müller T, Dandekar T, Pollack JD (May 2004). "Phylogeny of Firmicutes with special reference to Mycoplasma (Mollicutes) as inferred from phosphoglycerate kinase amino acid sequence data". Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. (Comparative Study) 54 (Pt 3): 871–5. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.02868-0. PMID 15143038.

- ↑ J.P. Euzéby. "Firmicutes". List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN). Retrieved 2013-03-20.

- ↑ Sayers; et al. "Firmicutes". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) taxonomy database. Retrieved 2013-03-20.

- ↑ All-Species Living Tree Project."16S rRNA-based LTP release 111 (full tree)" (PDF). Silva Comprehensive Ribosomal RNA Database. Retrieved 2013-03-20.

- ↑ Ley RE, Peterson DA, Gordon JI (2006). "Ecological and evolutionary forces shaping microbial diversity in the human intestine". Cell (Review) 124 (4): 837–48. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.017. PMID 16497592.

- ↑ Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI (2006). "Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity". Nature (Clinical Trial) 444 (7122): 1022–3. doi:10.1038/4441022a. PMID 17183309.

- ↑ Henig, Robin Marantz (2006-08-13). "Fat Factors". New York Times Magazine. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ↑ Ley RE, Bäckhed F, Turnbaugh P, Lozupone CA, Knight RD, Gordon JI (August 2005). "Obesity alters gut microbial ecology". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. (Research Support) 102 (31): 11070–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.0504978102. PMC 1176910. PMID 16033867. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ↑ Haakensen M, Dobson CM, Deneer H, Ziola B (July 2008). "Real-time PCR detection of bacteria belonging to the Firmicutes Phylum". Int. J. Food Microbiol. (Research Support) 125 (3): 236–41. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.04.002. PMID 18501458. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

External links

- Phylum "Firmicutes" - J.P. Euzéby: List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||