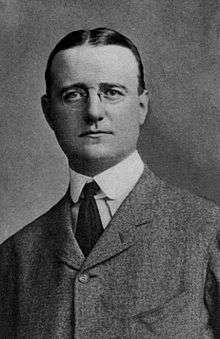

Finley Peter Dunne

| Finley Peter Dunne | |

|---|---|

|

Finley Peter Dunne | |

| Born |

July 10, 1867 Chicago |

| Died |

April 24, 1936 (aged 68) New York City, New York |

| Spouse(s) | Margaret Ives Abbott |

Finley Peter Dunne (July 10, 1867 – April 24, 1936) was an American humorist and writer from Chicago. In 1898 Dunne published Mr. Dooley in Peace and War, a collection of his nationally syndicated Mr. Dooley sketches.[1] Speaking with the thick verbiage and accent of an Irish immigrant from County Roscommon, the fictional Mr. Dooley expounded upon political and social issues of the day from his South Side Chicago Irish pub.[2] Dunne's sly humor and political acumen won the support of President Theodore Roosevelt, a frequent target of Mr. Dooley's barbs.[3] Dunne's sketches became so popular and such a litmus test of public opinion that they were read each week at White House cabinet meetings.[4]

Early life

Dunne was born in Chicago on July 10, 1867, was educated in the Chicago public schools (graduating from high school last in his class), and, at age 17, in 1884, began his newspaper career as a reporter/editor for the Chicago Telegram.[5] He was then with the Chicago News from 1884–88, the Chicago Times in 1888, the Chicago Tribune in 1889, the Chicago Herald in 1889, and the Chicago Journal in 1897. Originally named Peter Dunne, to honor his mother, who had died when he was in high school, he took her family name as his middle name some time before 1886, going by PF Dunne, reversed the two names in 1888, for Finley P. Dunne, and later used simply the initials, FP Dunne.[6] His sister, Amelia Dunne Hookway, was a prominent educator and high school principal in Chicago; the former Hookway School was named in her honor.

Mr. Dooley

The first Dooley articles appeared when Dunne was chief editorial writer for the Chicago Post, and for a number of years he wrote the pieces without a byline or initials. They were paid for at the rate of $10 each above his newspaper pay. A contemporary wrote of his Mr. Dooley sketches that "there was no reaching for brilliancy, no attempt at polish. The purpose was simply to amuse. But it was this very ease and informality of the articles that caught the popular fancy. The spontaneity was so genuine; the timeliness was so obvious."[7] In 1898, he wrote a Dooley piece that celebrated the victory of Commodore George Dewey over the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay—and this piece attracted national attention. Within a short time, weekly Dooley essays were syndicated across the country.[8]

In 1899, under the title Mr Dooley in Peace and War, a collection of the pieces was brought out in book form, received rave reviews from the critics, and was on the best seller list for a year. Dunne moved to New York as a full-time writer and national literary figure.

Selections from Dooley were read at meetings of the presidential cabinet. Theodore Roosevelt was a fan, despite the fact that he was one of Dunne's favorite targets. When Roosevelt published his book, The Rough Riders, Dunne wrote a tongue-in-cheek review mocking the war hero with the punchline "if I was him I'd call th' book 'Alone in Cubia'" and the nation roared.[9] Roosevelt wrote to Dunne: "I regret to state that my family and intimate friends are delighted with your review of my book. Now I think you owe me one; and I shall expect that when you next come east you pay me a visit. I have long wanted the chance of making your acquaintance."

The two finally met at the Republican Convention in 1900, where Roosevelt gave him a news scoop—he would accept the nomination as vice presidential candidate. In later years, Dunne was a frequent guest for dinner and weekends at the White House.

Dunne wrote more than 700 Dooley pieces, about a third of which were printed in eight books. Their era of influence ended with the start of World War I. After Dooley became popular, Dunne left Chicago and lived in New York, where he wrote books and articles and edited The American Magazine, Metropolitan Magazine and Collier's Weekly, becoming a beloved figure in club and literary circles.

Dunne's "Dooley" essays were based on realistic depictions of working-class life, and did not reflect the idealism of most political commentators of the Progressive Era. Fanning says:

- Dunne did not share the faith ... in progressive reform. He viewed the world as fallen and essentially unimprovable, and many Dooley pieces reflect their author's tendency toward fatalism.[10]

Personal life

On December 10, 1902, Dunne married Margaret Ives Abbott (1876–1955), a society woman in Chicago and prominent golfer. She continued to play golf while she and Dunne were raising their four children, Finley Peter Dunne, Jr., screenwriter/director Philip Dunne, and twins Peggy and Leonard.

He died in New York on April 24, 1936.

Legacy

Dunne's historical significance was apparent at the time of his death. Elmer Ellis, historian at (and later president of) the University of Missouri, wrote a biography of Dunne published in 1941.[11]

He coined numerous political quips over the years; one of the best-known aphorisms he originated is "politics ain't beanbag", referring to the rough side of political campaigns.[12]

As a journalist in the age of "muckraking journalism", Dunne was aware of the power of institutions, including his own. Writing as Dooley, Dunne once wrote the following passage mocking hypocrisy and self-importance in the newspapers themselves:

- "Th newspaper does ivrything f'r us. It runs th' polis foorce an' th' banks, commands th' milishy, controls th' ligislachure, baptizes th' young, marries th' foolish, comforts th' afflicted, afflicts th' comfortable, buries th' dead an' roasts thim aftherward".

The expression has been borrowed and altered in many ways over the years:

- Clare Boothe Luce employed a variation of it in a tribute to Eleanor Roosevelt, "Mrs. Roosevelt has done more good deeds on a bigger scale for a longer time than any woman who ever appeared on the public scene. No woman has ever so comforted the distressed — or so distressed the comfortable."[13]

- A version showed up in a line delivered by Gene Kelly in the 1960 film, Inherit the Wind. Kelly (E.K. Hornbeck) says, "Mr. Brady, it is the duty of a newspaper to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable".

- Appalachian political activist and attorney Larry Harless, known best for his numerous attempts to derail funding for Pullman Square often stated that he tried "to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable".[14]

- The American poet Lucille Clifton is often quoted as saying that she aimed in her poetry to "comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable."[15]

According to an article in the November 5, 2006 edition of the New York Times, he coined the truism, often wrongly attributed to Tip O'Neill, that "all politics is local."

Works

- Mr. Dooley in Peace and in War (1899)

- Mr. Dooley in the Hearts of His Countrymen (1899)

- Mr. Dooley's Philosophy (1900)

- Mr. Dooley's Opinions (1901)

- Observations by Mr. Dooley (1902)

- Dissertations by Mr. Dooley (1906)

- Mr. Dooley Says (1910)

- Mr. Dooley on Making a Will and Other Necessary Evils (1919)

References

- ↑ "Literary Notes." The Independent. New York: March 16, 1899; Vol. 51, Iss. 2624. 771.

- ↑ Dunne, Finley Peter. Mr. Dooley in Peace and in War.Boston: Small, Maynard & Company. 1898. vii-xiii

- ↑ Gibson, William M. Theodore Roosevelt Among the Humorists: W.D. Howells, Mark Twain, and Mr. Dooley. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. 1980.

- ↑ Fanning, Charles. Finley Peter Dunne & Mr. Dooley: The Chicago Years. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky. 1978. 199.

- ↑ Lowe, John. "Finley Peter Dunne." The Literary Encyclopedia. 17 July 2001.

- ↑ Lowe, John. "Finley Peter Dunne." The Literary Encyclopedia. 17 July 2001.

- ↑ Harkins, E. F. "Little Pilgrimages Among the Men Who Have Written Famous Books. No. 14.; Finley Peter Dunne." The Literary World: a Monthly Review of Current Literature. Boston: Aug. 1904. Vol. 35, Iss. 8. 215-6.

- ↑ "Mr. Dooley's Creator, Finley Peter Dunne." Current Literature. New York: Nov. 1899. Vol. XXVI, No. 5. 402.

- ↑ Dunne, Finley Peter. "Mr. Dooley: X - He Reviews a Book." Harper's Weekly. 25 November 1899.

- ↑ Fanning (2000)

- ↑ Elmer Ellis, Mr. Dooley's America: A Life of Finley Peter Dunne, (Knopf, 1941).

- ↑ "Mitt Romney Incapable of Correctly Reciting Famous Political Aphorism", by Dan Amira, New York, January 30, 2012.

- ↑ Bonnie Angelo (2007). First Families: The Impact of the White House on Their Lives. HarperCollins. p. 292.

- ↑ Bob Weaver (April 2, 2004). "Larry's Sun Did Not Shine Yesterday". The Hur Herald.

- ↑ Quoted in: Shockley, Evie (2015). "Clifton, Lucille (1936-2010)." In Jeffrey Gray, Mary McAleer Balkun, and James McCorkle (Eds.), American Poets and Poetry: From the Colonial Era to the Present (Santa Barbara, Calif.: Greenwood), p. 111-116; here: p. 111.

- ↑ Grace Eckley, Finley Peter Dunne. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1981.

Further reading

- Eckley, Grace. Finley Peter Dunne (Twayne, 1981)

- Ellis, Elmer. Mr. Dooley's America: A Life of Finley Peter Dunne (Knopf, 1941).

- Fanning, Charles. Finley Peter Dunne and Mr. Dooley: The Chicago Years (2nd ed., University Press of Kentucky, 2015)

- Fanning, Charles. "Dunne, Finley Peter" American National Biography Online (2000) Access Date: Tue Oct 13 2015

- Rees, John. "An Anatomy of Mr. Dooley's Brogue." Studies in American Humor (1986): 145-157.

- Rees, John O. "A Reading of Mr. Dooley." Studies in American Humor (1989): 5-31.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Finley Peter Dunne. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Finley Peter Dunne |

- Works by Finley Peter Dunne at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Finley Peter Dunne at Internet Archive

- Works by Finley Peter Dunne at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Finley Peter Dunne (1898). Mr. Dooley in Peace and in War. Small, Maynard & company.

- Finley Peter Dunne (1899). Mr. Dooley in the Hearts of His Countrymen. Small, Maynard & company.

- Finley Peter Dunne, Frederick Burr, Opper, Frederick Burr Opper, Edward Windsor Kemble, William Nicholson (1900). Mr. Dooley's Philosophy. William Heinemann.

- Finley Peter Dunne (1901). Mr. Dooley's Opinions. Harper.

- Finley Peter Dunne (1902). Observations by Mr. Dooley. R.H. Russell.

- Finley Peter Dunne (1906). Dissertations by Mr. Dooley. Harper.

- Finley Peter Dunne (1910). Mr. Dooley Says ... C. Scribner's Sons.

|