σ-finite measure

In mathematics, a positive (or signed) measure μ defined on a σ-algebra Σ of subsets of a set X is called finite if μ(X) is a finite real number (rather than ∞). The measure μ is called σ-finite if X is the countable union of measurable sets with finite measure. A set in a measure space is said to have σ-finite measure if it is a countable union of sets with finite measure.

A different but related notion is s-finiteness. A measure  is s-finite if and only if there exists a sequence of finite measures

is s-finite if and only if there exists a sequence of finite measures  , that is: m is the countable sum of finite measures.

, that is: m is the countable sum of finite measures.

Examples

Lebesgue measure

For example, Lebesgue measure on the real numbers is not finite, but it is σ-finite. Indeed, consider the closed intervals [k, k + 1] for all integers k; there are countably many such intervals, each has measure 1, and their union is the entire real line.

Counting measure

Alternatively, consider the real numbers with the counting measure; the measure of any finite set is the number of elements in the set, and the measure of any infinite set is infinity. This measure is not σ-finite, because every set with finite measure contains only finitely many points, and it would take uncountably many such sets to cover the entire real line. But, the set of natural numbers  with the counting measure is σ -finite.

with the counting measure is σ -finite.

Locally compact groups

Locally compact groups which are σ-compact are σ-finite under Haar measure. For example, all connected, locally compact groups G are σ-compact. To see this, let V be a relatively compact, symmetric (that is V = V−1) open neighborhood of the identity. Then

is an open subgroup of G. Therefore H is also closed since its complement is a union of open sets and by connectivity of G, must be G itself. Thus all connected Lie groups are σ-finite under Haar measure.

Negative examples

Any non-trivial measure taking only the two values 0 and  is clearly non σ-finite. One example in

is clearly non σ-finite. One example in  is: for all

is: for all  ,

,  if and only if A is not empty; another one is: for all

if and only if A is not empty; another one is: for all  ,

,  if and only if A is uncountable, 0 otherwise. Incidentally, both are translation-invariant.

if and only if A is uncountable, 0 otherwise. Incidentally, both are translation-invariant.

Properties

The class of σ-finite measures has some very convenient properties; σ-finiteness can be compared in this respect to separability of topological spaces. Some theorems in analysis require σ-finiteness as a hypothesis. Usually, both the Radon–Nikodym theorem and Fubini's theorem are stated under an assumption of σ-finiteness on the measures involved. However, as shown in Segal's paper Equivalences of measure spaces (Am. J. Math. 73, 275 (1953)) they require only a weaker condition, namely localisability.

Though measures which are not σ-finite are sometimes regarded as pathological, they do in fact occur quite naturally. For instance, if X is a metric space of Hausdorff dimension r, then all lower-dimensional Hausdorff measures are non-σ-finite if considered as measures on X.

Equivalence to a probability measure

Any σ-finite measure μ on a space X is equivalent to a probability measure on X: let Vn, n ∈ N, be a covering of X by pairwise disjoint measurable sets of finite μ-measure, and let wn, n ∈ N, be a sequence of positive numbers (weights) such that

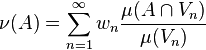

The measure ν defined by

is then a probability measure on X with precisely the same null sets as μ.

Relation to s-finiteness

If m is a σ-finite measure, then it is s-finite. However, the converse is not true.