Filibuster in the United States Senate

| This article is part of a series on the |

| United States Senate |

|---|

|

| History of the United States Senate |

| Members |

|

|

| Politics and procedure |

| Places |

A filibuster in the United States Senate is a dilatory or obstructive tactic used in the United States Senate to prevent a measure from being brought to a vote. The most common form of filibuster occurs when a senator attempts to delay or entirely prevent a vote on a bill by extending the debate on the measure, but other dilatory tactics exist. The rules permit a senator, or a series of senators, to speak for as long as they wish and on any topic they choose, unless "three-fifths of the Senators duly chosen and sworn"[1] (usually 60 out of 100 senators) brings debate to a close by invoking cloture under Senate Rule XXII.

According to the Supreme Court ruling in United States v. Ballin (1892), changes to Senate rules could be achieved by a simple majority. Nevertheless, under current Senate rules, a rule change itself could be filibustered, with the votes of two-thirds of those senators present and voting (as opposed to the normal three-fifths of those sworn) needed to end debate.[1] Despite this written requirement, the possibility exists that the Senate's presiding officer could on motion declare a Senate rule unconstitutional, which decision can be upheld by a simple majority vote of the Senate.

Early experience

In 1789, the first U.S. Senate adopted rules allowing the Senate to move the previous question which meant ending debate and proceeding to a vote. Former Vice President Aaron Burr argued in 1806 that the motion regarding the previous question was redundant, had only been exercised once in the preceding four years, and should be eliminated.[2] In that same year, the Senate agreed, recodifying its rules, and thus the potential for a filibuster sprang into being.[2] Because the Senate created no alternative mechanism for terminating debate, the filibuster became an option for delay and blocking of floor votes.

The filibuster remained a solely theoretical option until the late 1830s. The first Senate filibuster occurred in 1837.[3] In 1841, a defining moment came during debate on a bill to charter the Second Bank of the United States. Senator Henry Clay tried to end debate via majority vote. Senator William R. King threatened a filibuster, saying that Clay "may make his arrangements at his boarding house for the winter". Other senators sided with King, and Clay backed down.[2]

Modern scholars point out that in practice, narrow Senate majorities would be able to enact legislation, by changing the rules, but only on the first day of the session in January or March.[4] This could be done if the minority used a filibuster to prevent, instead of merely to delay, votes on measures supported by a bare majority.[4]

20th century and the emergence of cloture

In 1917, a rule allowing for the cloture of debate (ending a filibuster) was adopted by the Democratic Senate[5] at the urging of President Woodrow Wilson[6] after a group of 12 anti-war senators managed to kill a bill that would have allowed Wilson to arm merchant vessels in the face of unrestricted German submarine warfare. From 1917 to 1949, the requirement for cloture was two-thirds of those voting.[7] Despite the formal requirement, however, political scientist David Mayhew has argued that in actual practice, it was unclear whether a filibuster could be sustained against majority opposition.[8]

| Longest Filibusters in the U.S. Senate since 1900[9] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Senator | Date (began) | Measure | Hours & minutes | |

| 1 | Strom Thurmond (D-SC) | August 28, 1957 | Civil Rights Act (1957) | 24:18 |

| 2 | Alfonse D'Amato (R-NY) | October 17, 1986 | Defense Authorization Act (1987), amendment | 23:30 |

| 3 | Wayne Morse (I-OR) | April 24, 1953 | Submerged Lands Act (1953) | 22:26 |

| 4 | Robert M. La Follette, Sr. (R-WI) | May 29, 1908 | Aldrich–Vreeland Act (1908) | 18:23 |

| 5 | William Proxmire (D-WI) | September 28, 1981 | Debt ceiling increase (1981) | 16:12 |

| 6 | Huey Long (D-LA) | June 12, 1935 | National Industrial Recovery Act (1933), amendment | 15:30 |

| 7 | Alfonse D'Amato (R-NY) | October 5, 1992 | Revenue Act (1992), amendment | 15:14 |

| 8 | Robert Byrd (D-WV) | June 9, 1964 | Civil Rights Act (1964) | 14:13 |

| 9 | Rand Paul (R-KY) | March 6, 2013 | Confirmation of John Brennan as Director of the CIA | 12:52 |

| 10 | Rand Paul (R-KY) | May 20, 2015 | Patriot Act (2001) renewal | 10:31 |

During the 1930s, Senator Huey Long used the filibuster to promote his populist policies. The Louisiana senator recited Shakespeare and read out recipes for "pot-likkers" during his filibusters, one of which occupied 15 hours of "debate".[6]

In 1946, Southern senators blocked a vote on a bill proposed by Democrat Dennis Chavez of New Mexico (S. 101) that would have created a permanent Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) to prevent discrimination in the work place. The filibuster lasted weeks, and Senator Chavez was forced to remove the bill from consideration after a failed cloture vote even though he had enough votes to pass the bill. As civil rights legislation continued to loom, the Senate revised the cloture rule in 1949 to permit the Senate to invoke cloture on any measure or motion only if two-thirds of the entire Senate membership voted in favor of a cloture motion.[10]

In 1953, Senator Wayne Morse set a record by filibustering for 22 hours and 26 minutes while protesting the Tidelands Oil legislation. Senator Strom Thurmond broke this record in 1957 by filibustering the Civil Rights Act of 1957 for 24 hours and 18 minutes,[11] although the bill ultimately passed. In 1959, the Senate restored the cloture threshold to two-thirds of those voting.[10]

One of the most notable filibusters of the 1960s occurred when southern Democratic senators attempted to block the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by making a filibuster that lasted for 75 hours, which included a 14 hour and 13 minute address by Senator Robert Byrd. The filibuster failed when the Senate invoked cloture for only the second time since 1927.[12]

After a series of filibusters in the 1960s over civil rights legislation, the Senate put a "two-track system" into place in the early 1970s under the leadership of Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield and Byrd, who was at that time serving as Senate Majority Whip. Before the introduction of tracking, a filibuster would stop the Senate from moving on to any other legislative activity. Tracking allows the majority leader – with unanimous consent or the agreement by the minority leader – to have more than one bill pending on the floor as unfinished business. Under the "two-track system", the Senate can have two or more pieces of legislation pending on the floor simultaneously by designating specific periods during the day when each matter or measure will be considered.[13][14][15][16][17][18]

In 1975 the Democratic-controlled Senate[5] revised its cloture rule so that three-fifths of the senators sworn (usually 60 senators) could limit debate, except on votes to change Senate rules, which require two-thirds to invoke cloture.[19][20] The Senate experimented with a rule to remove the need to speak on the floor to filibuster ("talking filibuster"), thus allowing for "virtual filibusters".[21] Another type of filibuster used in the Senate, the post-cloture filibuster (using points of order to consume time, since they are not counted as part of the limited time provided for debate), was eliminated as an effective delay technique by a rule change in 1979.[22][23][24]

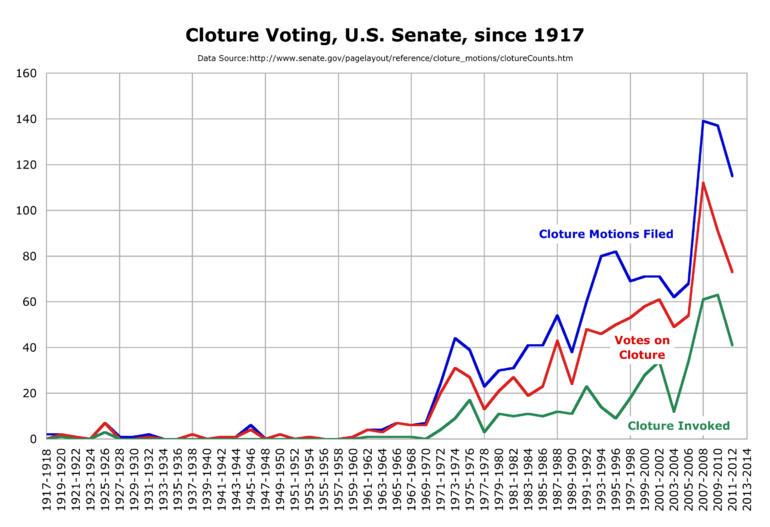

The filibuster or the threat of a filibuster remains an important tactic that allows a minority to affect legislation. The perceived threat of a filibuster has tremendously increased since the 1960s, as suggested by the increase in cloture motions filed.[26] A motion for cloture is filed not only to overcome filibusters in progress, but also to pre-empt ones that are only anticipated.[27] In the 1960s, no Senate term had more than seven votes on cloture.[25] By the first decade of the 21st century, the number of votes on cloture per Senate term had risen to no fewer than forty-nine.[25][28] The 110th Congress broke the record for cloture votes, reaching 112 at the end of 2008.[25]

Current U.S. legislative practice

The way Congress develops tax and spending legislation is guided by a set of specific procedures laid out in the Congressional Budget Act of 1974.[29] Under the Budget Act, Congress is required to develop a "budget resolution" setting aggregate limits on spending and targets for federal revenue. If a budget resolution that passes both chambers includes language known as a "reconciliation directive," a process is triggered to produce a "reconciliation bill" that goes to the floor for an up-or-down vote, with only limited opportunity for amendment. Under the procedures for reconciliation bills, debate in both houses is limited to 20 hours, and no Senate filibusters are allowed. A budget resolution is not signed by the President and does not become law, although it can be enforced during Congressional debates under internal rules; a reconciliation bill is signed by the President and becomes law. Congress has used reconciliation occasionally for non-budget legislation, including rewriting health care and welfare policy, as the Republican majority did in passing major welfare reform in 1996.[30] However, at the beginning of the 110th Congress, both chambers adopted rules requiring that reconciliation be used solely for deficit reduction.[31]

A filibuster can be defeated by the majority party if they leave the debated issue on the agenda indefinitely, without adding anything else. Indeed, Thurmond's attempt to filibuster the Civil Rights Act of 1957 was defeated when Senate Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson refused to refer any further business to the Senate, which required the filibuster to be kept up indefinitely. Instead, the opponents were all given a chance to speak, and the matter eventually was forced to a vote. Thurmond's aforementioned stall holds the record for the longest filibuster in U.S. Senate history at 24 hours, 18 minutes.[11]

Even if a filibuster attempt is unsuccessful, the process takes floor time. In recent years the majority has preferred to avoid filibusters by moving to other business when a filibuster is threatened and attempts to achieve cloture have failed.[27]

There have been attempts to challenge the constitutionality of the filibuster. However, the courts have dismissed these cases for lack of standing and because Article I of the United States Constitution gives each chamber of Congress the power to determine the rules of its own proceedings.[32]

On December 6, 2012, Senator Mitch McConnell (R-KY), Senate Minority Leader, became the first senator to filibuster his own proposal. Without giving a lengthy speech, he invoked the rules of filibuster on his bill to raise the passage threshold to 60 votes. McConnell had attempted to force the opposition Democrats, who had a majority in the Senate, to refuse to pass what would have been a politically costly measure, but one that would nonetheless solve the current ongoing debt ceiling deadlock. When Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-NV) chose to call a vote on the proposal regardless, McConnell immediately invoked the rules of filibusters on his own proposal, effectively doing the first self-filibuster in Senate history.[33]

Recent filibusters of nominations

In 2005, a group of Republican senators led by Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist, responding to the Democrats' threat to filibuster some judicial nominees of President George W. Bush to prevent a vote on the nominations, floated the idea of having Vice President Dick Cheney, as President of the Senate, rule from the chair that a filibuster on judicial nominees was inconsistent with the constitutional grant of power to the president to name judges with the advice and consent of the Senate (interpreting "consent of the Senate" to mean "consent of a simple majority of Senators," not "consent under the Senate rules").[34] Senator Trent Lott, the junior Republican senator from Mississippi, had named the plan the "nuclear option." Republican leaders preferred to use the term "constitutional option," although opponents, including then-Senator Obama, and some supporters of the plan continued to use "nuclear option." In 2005, Obama opposed the change before supporting it in 2013. He said on the Senate floor "I urge my Republican colleagues not to go through with changing these rules. In the long run it is not a good result for either party. One day Democrats will be in the majority again and this rule change will be no fairer to a Republican minority than it is to a Democratic minority." [35] In 2013, Obama supported the rule change as a Democratic President when Democrats were the majority in the Senate.[35]

On May 23, 2005, a group of fourteen senators was dubbed the Gang of 14, consisting of seven Democrats and seven Republicans. The seven Democrats promised not to filibuster Bush's nominees except under "extraordinary circumstances," while the seven Republicans promised to oppose the nuclear option unless they thought a nominee was being filibustered that was not under "extraordinary circumstances." Specifically, the Democrats promised to stop the filibuster on Priscilla Owen, Janice Rogers Brown, and William H. Pryor, Jr., who had all been filibustered in the Senate before. In return, the Republicans would stop the effort to ban the filibuster for judicial nominees. "Extraordinary circumstances" was not defined in advance. The term was open for interpretation by each senator, but the Republicans and Democrats would have had to agree on what it meant if any nominee were to be blocked.

On January 3, 2007, at the end of the second session of the 109th United States Congress, this agreement expired.

In the 2007–08 session of Congress, there were 112 cloture votes[25] and some have used this number to argue an increase in the number of filibusters occurring in recent times. However, the Senate leadership has increasingly utilized cloture as a routine tool to manage the flow of business, even in the absence of any apparent filibuster. For these reasons, the presence or absence of cloture attempts cannot be taken as a reliable guide to the presence or absence of a filibuster. Inasmuch as filibustering does not depend on the use of any specific rules, whether a filibuster is present is always a matter of judgment.[27]

In December 2009, Senator Sheldon Whitehouse claimed there were over 100 filibusters and acts of obstruction during the 111th Congress.[36] In March 2010, freshman senator Al Franken attacked the majority of the filibusters—some on matters which later passed with little controversy—as a "perversion of the filibuster".[37]

From April to June 2010, the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration held a series of monthly public hearings entitled "Examining the Filibuster" to examine the history and use of the filibuster in the Senate.[38]

In response to the use of the filibuster in the 111th Congress, all Democratic senators returning to the 112th Congress signed a petition to Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, requesting that the filibuster be reformed, including abolishing secret holds and reducing the amount of time given to post-cloture debate.

Changes in 2013

Negotiations between the two parties resulted in two packages of amendments to the rules on filibusters being approved by the Senate on January 25, 2013.[39] Changes to the standing orders affecting just the 2013-14 Congress were passed by a vote of 78 to 16, allowing the Senate majority leader to prohibit a filibuster on a motion to begin consideration of a bill.[39] Changes to the permanent Senate rules were passed by a vote of 86 to 9.[39] The changes occurred through Senate Resolution 15 and Senate Resolution 16; Senate Resolution 15 applies only to the 113th session, while Senate Resolution 16 changed two standing rules of the Senate.[40]

The series of changes to the filibuster rules announced represented a compromise between the major reforms put forward by some Democratic senators and the changes preferred by Republican senators.[41] Those seeking reform, including Democrats and liberal interest groups, had originally proposed a variety of strong reforms including: ending the filibuster completely; banning the use of filibusters on the motion to proceed; re-introducing the "talking filibuster" where the minority would have to remain on the Senate floor and speak in order to impede passage of a vote; banning the use of filibusters on House-Senate conferences; and forcing the minority to produce 41 votes in order to block cloture.[42][43] These more extensive reforms of the filibuster could only have been implemented by a decision from the Senate's presiding officer declaring it unconstitutional.

The new rules remove the requirement of 60 votes in order to begin debate on legislation and allow the minority two amendments to measures that reach the Senate floor, a change implemented as a standing order that expires at the end of the current term.[43][44] In the new rules, the amount of time to debate following a motion to proceed has been reduced from 30 hours to four. Additionally, a filibuster on the motion to proceed will be blocked if a petition is signed by eight members of the minority, including the minority leader.[44] For district court nominations, the new rules reduce the required time before the nominee is confirmed after cloture from 30 hours to two hours.[44] Under the new rules, if senators wish to block a bill or nominee after the motion to proceed, they will need to be present in the Senate and debate.[45][43] Following the changes, 60 votes are still required to overcome a filibuster to pass legislation and confirm nominees and the "silent filibuster"—where senators can filibuster even if they leave the floor—remained in place.[45][43]

Following the announcement of the new rules, Senator Dick Durbin, who was involved in the negotiations, stated that the deal reached was true agreement between the majority and minority leaders, and was overwhelmingly supported by Senate Democrats.[44] However, the agreement was negatively received by liberal interest groups including CREDO,[44] Fix the Senate Now, a coalition of approximately 50 progressive and labor organizations, and the Progressive Change Campaign Committee, both of whom had advocated for eliminating the "silent filibuster" on the grounds that it allows Republicans to filibuster progressive bills.[45] Liberal independent Senator Bernie Sanders argued that the requirement for 60 votes to pass legislation makes it "impossible" to deal with the crises faced by the United States.[45] Conservatives also criticized the reforms, arguing that the changes negatively impacted the minority party. In particular, Heritage Action for America argued that reducing the length of time for debate allows senior lawmakers to "avoid accountability". Additionally, Senator Rand Paul criticized the rules change for limiting the "ability of Senators to offer amendments".[45]

On March 6, 2013, Senator Rand Paul launched a talking filibuster to stall John Brennan's nomination confirmation vote for the position of Director of the CIA,[46] demanding an answer from the Obama Administration to the question: "Should a President be allowed to target and kill an American by drone attack, on American soil, without due process?"[47][48] John Brennan was considered to be the main architect of the drone program.[46] After 12 hours and 52 minutes of talking, it became the 9th longest filibuster in U.S. history (until October 2013).[49] However, Paul's filibuster was widely considered a publicity stunt, since Attorney General Eric Holder had answered the question, "No," when posed by Senator Ted Cruz in a Senate Judicial Committee hearing hours earlier.[50]

Use of "nuclear option" in November 2013

On November 21, 2013, the Senate used the so-called "nuclear option," voting 52-48, with all Republicans and 3 Democrats voting against, to eliminate the use of the filibuster on executive branch nominees and judicial nominees other than to the Supreme Court. At the time of the vote there were 59 executive branch nominees and 17 judicial nominees awaiting confirmation.[51]

The Democrats' stated motivation for this change was what they saw as expansion of filibustering by Republicans during the Obama administration, especially with respect to nominations for the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit,[52] which "Republicans said they wanted to refuse Mr. Obama any more appointments to the appeals court...."[53] Republicans had asserted that the D.C. Circuit was underworked,[51] and also cited the need for cost reduction by reducing the number of judges in that circuit.[54] Democrats responded that Republicans had not raised these concerns earlier when President George W. Bush had made nominations to this court, and also cited the need to maintain the size of the court because of the complexity of the agency cases this court hears.[55][56]

As of November 2013, President Obama presented 79 nominees who received a vote to end debate (called "cloture" votes), compared to just 38 votes received during the preceding eight years under George W. Bush.[57] However, most of those cloture votes successfully ended debate, and therefore most filibustered nominees cleared the filibuster hurdle; Obama won Senate confirmation for 30 out of 42 federal appeals court nominations, compared with Bush's 35 out of 52.[57][58] Regarding President Obama's federal district court nominations, the Senate approved 143 of 173 as of November 2013, compared to George W. Bush's 170 of 179, Bill Clinton's 170 of 198, and George H.W. Bush's 150 of 195.[57][59] Filibusters were used to block (at least temporarily) 20 Obama nominations to U.S. District Court positions, compared to 3 times in previous U.S. history;[60] Republicans ultimately allowed confirmation of 19 out of those 20.[61]

Senate Democrats who chose the "nuclear option" also did so out of frustration with filibusters of executive branch nominees, for agencies such as the Federal Housing Finance Agency.[52]

Post-2013

In 2015, Republicans took control of the Senate, and kept the 2013 rules in place.[62] Senators continued to discuss the future of the filibuster. Republican Senators Lamar Alexander and Mike Lee proposed ending the use of the filibuster for Supreme Court nominees, while other Senators favored the status quo.[63] A third camp favored restoring the filibuster for all nominations.[63] In October 2015, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell convened a task force to consider eliminating filibusters on motions to proceed.[62]

Other forms of filibuster

While talking out a measure is the most common form of filibuster in the Senate, other means of delaying and killing legislation are available. Because the Senate routinely conducts business by unanimous consent, one member can create at least some delay by objecting to the request. In some cases, such as considering a bill or resolution on the day it is introduced or brought from the House, the delay could be as long as a day.[64] However, because the delay is a legislative day, not a calendar day, the majority can mitigate it by briefly adjourning.[65]

In many cases, the result of an objection to a unanimous request will be the necessity of a vote. Forcing votes may not seem an effective delaying tool, but the cumulative effect of several votes, which are at least 15 minutes, can be substantial. In addition to objecting to routine requests, votes can be forced through dilatory motions to adjourn and through quorum calls. The intended purpose of a quorum call is to establish the presence of a constitutional quorum, but senators routinely use them to waste time while waiting for the next speaker to come to the floor or for leaders to negotiate off the floor. In those cases, a senator asks unanimous consent to dispense with the quorum call. If a member objects, the clerk must continue to call the roll of senators just as is done with a vote. When a call shows no quorum, the minority can force another vote by moving to request or compel the attendance of absent senators. Finally, senators can force votes by moving to adjourn or raising specious points of order and appealing the ruling of the chair.

The most effective methods of delay are those that force the majority to invoke cloture multiple times on the same measure. The most common example of this is to filibuster the motion to proceed to a bill, then filibuster the bill itself. The result is to force the majority to go through the entire cloture process twice in a row. Where, as is common, the majority seeks to pass a substitute amendment to the bill, a further cloture procedure is needed for the amendment.

The Senate is particularly vulnerable to serial cloture votes when it and the House have passed different versions of the same bill and want to go to conference (i.e., appoint a special committee of both houses to merge the bills). Normally, the majority asks unanimous consent to

- Insist on its amendment or amendments (or disagree to the House's amendments);

- Request (or agree to) a conference; and

- Authorize the presiding officer to appoint conferees (members of the special committee).

However, if the minority objects, each of those motions is debatable, and therefore subject to a filibuster, and are divisible, meaning the minority can force them to be debated (and filibustered) separately.[64] What's more, after the first two motions pass, but before the third does, senators can offer an unlimited number of motions to give the conferees non-binding instructions, which are debatable, amendable, and divisible.[66] As a result, a determined minority could cause a great deal of delay before a conference.

See also

| Look up filibuster in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Filibuster

- Obstructionism

- Cloture

- Nuclear option

- Reconciliation (United States Congress)

- Senate hold

- Senatorial courtesy

- Blue slip

- Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (a filibuster is a major plot element in the film)

References

- 1 2 "Precedence of motions (Rule XXII)". Rules of the Senate. United States Senate. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Gold, Martin (2008). Senate Procedure and Practice (2nd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-7425-6305-6. OCLC 220859622. Retrieved March 3, 2009.

- ↑ Binder, Sarah (April 22, 2010). "The History of the Filibuster". Brookings. Retrieved June 14, 2012.

- 1 2 Pildes, Rick (December 24, 2009). "The History of the Senate Filibuster". Balkinization. Retrieved March 1, 2010. Discussing Wawro, Gregory John; Schickler, Eric (2006). Filibuster: obstruction and lawmaking in the U.S. Senate. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-691-12509-1.

- 1 2 "Party Division in the Senate, 1789 – present". United States Senate. Retrieved February 14, 2007.

- 1 2 "Filibuster and Cloture". United States Senate. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ↑ "What is Rule 22?", Rule22 (blog), Word press, May 28, 2011

- ↑ Mayhew, David (January 2003). "Supermajority Rule in the US Senate" (PDF). PS: Political Science & Politics: 31, 34.

- ↑

- 1 2 "Changing the Rule". Filibuster. Washington, DC: CQ-Roll Call Group. 2010. Retrieved June 24, 2010.

- 1 2 "Strom Thurmond Biography". Strom Thurmond Institute. Retrieved January 6, 2009.

- ↑ "Civil Rights Filibuster Ended". Art & History Historical Minutes. United States Senate. Retrieved March 1, 2010.

- ↑ Erlich, Aaron (November 18, 2003). "Whatever Happened to the Old-Fashioned Jimmy Stewart-Style Filibuster?". HNN: George Mason University's History News Network. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ↑ Kemp, Jack (November 15, 2004). "Force a real filibuster, if necessary". Townhall. Retrieved March 1, 2010.

- ↑ Brauchli, Christopher (January 8–10, 2010). "A Helpless and Contemptible Body—How the Filibuster Emasculated the Senate". CounterPunch.

- ↑ Schlesinger, Robert (January 25, 2010). "How the Filibuster Changed and Brought Tyranny of the Minority". Politics & Policy. U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved June 24, 2010.

- ↑ Mariziani, Mimi and Lee, Diana (April 22, 2010). "Testimony of Mimi Marizani & Diana Lee, Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law, Submitted to the U.S. Senate Committee on Rules & Administration for the hearing entitled "Examining the Filibuster: History of the Filibuster 1789–2008"". Examining the Filibuster: History of the Filibuster 1789–2008. United States Senate Committee on Rules & Administration. p. 5. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ↑ Note: Senator Robert C. Byrd wrote in 1980 that he and Senator Mike Mansfield instituted the "two-track system" in the early 1970s with the approval and cooperation of Senate Republican leaders while he was serving as Senate Majority Whip. (Byrd, Robert C. (1991). "Party Whips, May 9, 1980". In Wendy Wolff. The Senate 1789–1989 2. Washington, D.C.: 100th Congress, 1st Session, S. Con. Res. 18; U.S. Senate Bicentennial Publication; Senate Document 100-20; U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 203. Retrieved June 30, 2010.).

- ↑ "Resolution to amend Rule XXII of the Standing Rules of the Senate". The Library of Congress. January 14, 1975. Retrieved February 18, 2010.

- ↑ Wawro, Gregory J. (April 22, 2010). "The Filibuster and Filibuster Reform in the U.S. Senate, 1917–1975; Testimony Prepared for the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration". Examining the Filibuster: History of the Filibuster 1789–2008. United States Senate Committee on Rules & Administration. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ↑ Understanding the Filibuster: Purpose and History of the Filibuster. No Labels.

- ↑ Byrd, Robert C. (April 22, 2010). "Statement of U.S. Senator Robert C. Byrd, Senate Committee on Rules and Administration, “Examining the Filibuster: History of the Filibuster 1789–2008.”". Examining the Filibuster: History of the Filibuster 1789–2008. United States Senate Committee on Rules & Administration. p. 2. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ↑ Bach, Stanley (April 22, 2010). "Statement on Filibusters and Cloture: Hearing before the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration". Examining the Filibuster: History of the Filibuster 1789–2008. United States Senate Committee on Rules & Administration. pp. 5–7. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ↑ Gold, Martin B. and Gupta, Dimple (Winter 2005). "The Constitutional Option to Change the Senate Rules and Procedures: A Majoritarian Means to Overcome the Filibuster" (PDF). Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy 28 (1): 262–64. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Senate Action on Cloture Motions". United States Senate. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ↑ "Political party (ab)use of the filibuster in the US Senate". Daily Kos. February 18, 2010. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Beth, Richard; Stanley Bach (March 28, 2003). Filibusters and Cloture in the Senate (PDF). Congressional Research Service. pp. 4, 9.

- ↑ Talev, Margaret (July 20, 2007). "Senate tied in knots by filibusters". The McClatchy Co. McClatchy Washington Bureau. Retrieved March 1, 2010.

- ↑ Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) (January 3, 2011). "Policy Basics: Introduction to the Federal Budget Process".

- ↑ Pianin, Eric (January 21, 2010). "How The Budget Reconciliation Process Works". Kaiser Health News.

- ↑ Heniff Jr., Bill; Lynch, Megan Suzanne; Tollestrup, Jessica (December 3, 2012). Introduction to the Federal Budget Process (PDF). Congressional Research Service (CRS).

- ↑ Denniston, Lyle (December 21, 2014). "Filibuster challenge fails". Scotusblog. Retrieved January 29, 2015.

- ↑ Grant, David (December 6, 2012). "Debt ceiling debate twist: Sen. Mitch McConnell filibusters himself". Yahoo! News. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ↑ Allen, Mike; Birnbaum, Jeffrey H. (May 18, 2005). "A Likely Script for The 'Nuclear Option'". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 20, 2009.

- 1 2 Bash, Dana; Barrett, Ted; Cohen, Tom (November 21, 2013). "Obama supports Senate's nuclear option to end some filibusters". CNN Politics. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ↑ Hulse, Carl; Herszenhorn, David M. (December 20, 2009). "Senate Debate on Health Care Exacerbates Partisanship". The New York Times. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

- ↑ Birkey, Andy (March 16, 2010). "Franken criticizes GOP ‘perversion of the filibuster’". The Minnesota Independent. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ↑ "Senate Rules Committee Holds Series of Hearings on the Filibuster". In The News. United States Senate Committee on Rules & Administration. June 9, 2010. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Karoun Demirjian (January 24, 2013). "Senate approves modest, not sweeping, changes to the filibuster". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ↑ Rybicki E. (2013). Changes to Senate Procedures in the 113th Congress Affecting the Operation of Cloture (S.Res. 15 and S.Res. 16). Congressional Research Service.

- ↑ Lengell, Sean; Dinan, Stephen (January 24, 2012). "‘Nuclear option’ averted as Senate leaders reach agreement on filibuster rules". The Washington Times. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- ↑ Graham, David A (January 24, 2013). "How Senate Graybeards Killed Real Filibuster Reform". The Atlantic. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Dwyer, Paula (January 25, 2013). "Reid Was Smart to Drop 'Nuclear Option'". Bloomberg. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Grim, Ryan; Stein, Sam; Siddiqui, Sabrina (January 24, 2013). "Harry Reid, Mitch McConnell Reach Filibuster Reform Deal". Huffington Post. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bolton, Alexander (January 24, 2013). "Liberals irate as Senate passes watered-down filibuster reform". The Hill. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- 1 2 Killough, Ashley (March 7, 2013). "Rand Paul's #filiblizzard filibuster". CNN. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

- ↑ Parker, Ashley (March 6, 2013). "Rand Paul Leads Filibuster of Brennan Nomination". The New York Times. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

- ↑ O'Keefe, Ed (March 6, 2013). "Rand Paul launches talking filibuster against John Brennan". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

- ↑ Camia, Catalina (March 7, 2013). "Rand Paul filibuster ranks among Senate's longest". USA Today. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

- ↑ "Rand Paul Exaggerates His Filibuster ‘Victory’". FactCheck. March 26, 2013.

- 1 2 Peters, Jeremy W. (November 21, 2013). "In Landmark Vote, Senate Limits Use of the Filibuster". New York Times.

- 1 2 Kathleen Hunter (November 21, 2013). "U.S. Senate changes rules to stop minority from blocking nominations". Concord Monitor.

- ↑ Jeremy W. Peters (October 31, 2013). "G.O.P. Filibuster of 2 Obama Picks Sets Up Fight". The New York Times.

- ↑ "GOP’s existential test: Why they’re really escalating a nuclear option crisis". Salon.com.

- ↑ Jeremy W. Peters (October 29, 2013). "Between Democrats and a Push for Filibuster Change, One Nominee". New York Times.

- ↑ Richard Wolf (November 21, 2013). "Senate fights over appeals court key to Obama agenda". USA Today.

- 1 2 3 Hook, Janet and Peterson, Kristina. "Senate Adopts New Rules on Filibusters", The Wall Street Journal (November 21, 2013).

- ↑ "Do Obama Nominees Face Stiffer Senate Opposition?", The Wall Street Journal (November 21, 2013).

- ↑ McMillion, Barry. "President Obama’s First-Term U.S. Circuit and District Court Nominations: An Analysis and Comparison with Presidents Since Reagan", Congressional Research Service (May 2, 2013).

- ↑ "Senate Votes For Nuclear Option", The Huffington Post (November 21, 2013).

- ↑ Kamen, Al. "Filibuster reform may not open confirmation floodgates", The Washington Post (November 22, 2013).

- 1 2 Bolton, Alexander (12 October 2015). "Senate Republicans open door to weakening the filibuster". The Hill. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- 1 2 Everett, Burgess (January 28, 2015). "SCOTUS filibuster trial balloon goes bust". Politico. Retrieved January 29, 2015.

- 1 2 Gregg, Senator Judd (December 1, 2009), To Republican Colleagues (Letter), Politico

- ↑ 2010 Congressional Record, Vol. 156, Page S1819 to S1821, where a brief adjournment was used for a similar reason.

- ↑ Riddick's Senate Procedure, "Instruction of Conferees", p. 479.