Fiducial inference

Fiducial inference is one of a number of different types of statistical inference. These are rules, intended for general application, by which conclusions can be drawn from samples of data. In modern statistical practice, attempts to work with fiducial inference have fallen out of fashion in favour of frequentist inference, Bayesian inference and decision theory. However, fiducial inference is important in the history of statistics since its development led to the parallel development of concepts and tools in theoretical statistics that are widely used. Some current research in statistical methodology is either explicitly linked to fiducial inference or is closely connected to it.

Background

The general approach of fiducial inference was proposed by Ronald Fisher.[1][2] Here "fiducial" comes from the Latin for faith. Fiducial inference can be interpreted as an attempt to perform inverse probability without calling on prior probability distributions.[3] Fiducial inference quickly attracted controversy and was never widely accepted. Indeed, counter-examples to the claims of Fisher for fiducial inference were soon published. These counter-examples cast doubt on the coherence of "fiducial inference" as a system of statistical inference or inductive logic. Other studies showed that, where the steps of fiducial inference are said to lead to "fiducial probabilities" (or "fiducial distributions"), these probabilities lack the property of additivity, and so cannot constitute a probability measure.

The concept of fiducial inference can be outlined by comparing its treatment of the problem of interval estimation in relation to other modes of statistical inference.

- A confidence interval, in frequentist inference, with coverage probability γ has the interpretation that among all confidence intervals computed by the same method, a proportion γ will contain the true value that needs to be estimated. This has either a repeated sampling (or frequentist) interpretation, or is the probability that an interval calculated from yet-to-be-sampled data will cover the true value. However, in either case, the probability concerned is not the probability that the true value is in the particular interval that has been calculated since at that stage both the true value and the calculated are fixed and are not random.

- Credible intervals, in Bayesian inference, do allow a probability to be given for the event that an interval, once it has been calculated does include the true value, since it proceeds on the basis that a probability distribution can be associated with the state of knowledge about the true value, both before and after the sample of data has been obtained.

Fisher designed the fiducial method to meet perceived problems with the Bayesian approach, at a time when the frequentist approach had yet to be fully developed. Such problems related to the need to assign a prior distribution to the unknown values. The aim was to have a procedure, like the Bayesian method, whose results could still be given an inverse probability interpretation based on the actual data observed. The method proceeds by attempting to derive a "fiducial distribution", which is a measure of the degree of faith that can be put on any given value of the unknown parameter and is faithful to the data in the sense that the method uses all available information.

Unfortunately Fisher did not give a general definition of the fiducial method and he denied that the method could always be applied. His only examples were for a single parameter; different generalisations have been given when there are several parameters. A relatively complete presentation of the fiducial approach to inference is given by Quenouille (1958), while Williams (1959) describes the application of fiducial analysis to the calibration problem (also known as "inverse regression") in regression analysis.[4] Further discussion of fiducial inference is given by Kendall & Stuart (1973).[5]

The fiducial distribution

Fisher required the existence of a sufficient statistic for the fiducial method to apply. Suppose there is a single sufficient statistic for a single parameter. That is, suppose that the conditional distribution of the data given the statistic does not depend on the value of the parameter. For example suppose that n independent observations are uniformly distributed on the interval ![[0,\omega]](../I/m/35e1c5c6c96f5944bf335b715fef7ca5.png) . The maximum, X, of the n observations is a sufficient statistic for ω. If only X is recorded and the values of the remaining observations are forgotten, these remaining observations are equally likely to have had any values in the interval

. The maximum, X, of the n observations is a sufficient statistic for ω. If only X is recorded and the values of the remaining observations are forgotten, these remaining observations are equally likely to have had any values in the interval ![[0,X]](../I/m/8bbf27840e4247fc0f60a34f43a0ba54.png) . This statement does not depend on the value of ω. Then X contains all the available information about ω and the other observations could have given no further information.

. This statement does not depend on the value of ω. Then X contains all the available information about ω and the other observations could have given no further information.

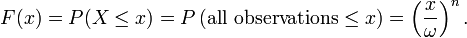

The cumulative distribution function of X is

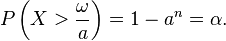

Probability statements about X/ω may be made. For example, given α, a value of a can be chosen with 0 < a < 1 such that

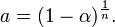

Thus

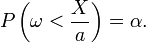

Then Fisher might say that this statement may be inverted into the form

In this latter statement, ω is now regarded as variable and X is fixed, whereas previously it was the other way round. This distribution of ω is the fiducial distribution which may be used to form fiducial intervals that represent degrees of belief.

The calculation is identical to the pivotal method for finding a confidence interval, but the interpretation is different. In fact older books use the terms confidence interval and fiducial interval interchangeably. Notice that the fiducial distribution is uniquely defined when a single sufficient statistic exists.

The pivotal method is based on a random variable that is a function of both the observations and the parameters but whose distribution does not depend on the parameter. Such random variables are called pivotal quantities. By using these, probability statements about the observations and parameters may be made in which the probabilities do not depend on the parameters and these may be inverted by solving for the parameters in much the same way as in the example above. However, this is only equivalent to the fiducial method if the pivotal quantity is uniquely defined based on a sufficient statistic.

A fiducial interval could be taken to be just a different name for a confidence interval and give it the fiducial interpretation. But the definition might not then be unique. Fisher would have denied that this interpretation is correct: for him, the fiducial distribution had to be defined uniquely and it had to use all the information in the sample.

Status of the approach

After its formulation by Fisher, fiducial inference quickly attracted controversy and was never widely accepted. Indeed, counter-examples to the claims of Fisher for fiducial inference were soon published.

Fisher admitted that "fiducial inference" had problems. Fisher wrote to George A. Barnard that he was "not clear in the head" about one problem on fiducial inference,[6] and, also writing to Barnard, Fisher complained that his theory seemed to have only "an asymptotic approach to intelligibility".[6] Later Fisher confessed that "I don't understand yet what fiducial probability does. We shall have to live with it a long time before we know what it's doing for us. But it should not be ignored just because we don't yet have a clear interpretation".[6]

Lindley[7] showed that fiducial probability lacked additivity, and so was not a probability measure. Cox points out[8] that the same argument applies to the so-called "confidence distribution" associated with confidence intervals, so the conclusion to be drawn from this is moot. Fisher sketched "proofs" of results using fiducial probability. When the conclusions of Fisher's fiducial arguments are not false, many have been shown to also follow from Bayesian inference.[5]

In 1978, JG Pederson wrote that "the fiducial argument has had very limited success and is now essentially dead."[9] Davison[10] wrote "A few subsequent attempts have been made to resurrect fiducialism, but it now seems largely of historical importance, particularly in view of its restricted range of applicability when set alongside models of current interest."

However, fiducial inference is still being studied[11][12] and other current work is ongoing under the name of confidence distributions.

Notes

- ↑ Fisher, R. A. (1935) "The fiducial argument in statistical inference", Annals of Eugenics, 8, 391–398.

- ↑ R. A. Fisher's Fiducial Argument and Bayes' Theorem by Teddy Seidenfeld

- ↑ Quenouille (1958), Chapter 6

- ↑ Williams (1959, Chapter 6)

- 1 2 Kendall, M.G., Stuart, A. (1973) The Advanced Theory of Statistics, Volume 2: Inference and Relationship, 3rd Edition, Griffin. ISBN 0-85264-215-6 (Chapter 21)

- 1 2 3 Zabell, S. L. (Aug 1992). "R. A. Fisher and Fiducial Argument". Statistical Science 7 (3): 369–387. doi:10.1214/ss/1177011233. JSTOR 2246073. (page 381)

- ↑ Sharon Bertsch McGrayne (2011) The Theory That Would Not Die. p. 133

- ↑ Cox (2006) p. 66

- ↑ Pederson, JG (1978). "Fiducial Inference". International Statistical Review 46 (2): 147–170. doi:10.2307/1402811. JSTOR 1402811. MR 0514060.

- ↑ Davison, A.C. (2001) "Biometrika Centenary: Theory and general methodology" Biometrika 2001 (page 12 in the republication edited by D. M. Titterton and David R. Cox)

- ↑ Hannig, J. (2009) "Generalized fiducial inference for wavelet regression" Biometrika, 96(4),847–860.

- ↑ Hannig, J. (2009) "On generalized fiducial inference", Statistica Sinica, 19, 491–544

References

- Cox, D. R. (2006). Principles of Statistical Inference, CUP. ISBN 0-521-68567-2.

- Fisher, R A (1956). Statistical Methods and Scientific Inference. New York: Hafner. ISBN 0-02-844740-9.

- Fisher, Ronald "Statistical methods and scientific induction" Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B 17 (1955), 69—78. (criticism of statistical theories of Jerzy Neyman and Abraham Wald from a fiducial perspective)

- Neyman, Jerzy (1956). "Note on an Article by Sir Ronald Fisher". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B 18 (2): 288–294. JSTOR 2983716. (reply to Fisher 1955, which diagnoses a fallacy of "fiducial inference")

- Tukey, J W, ed., ed. (1950). R.A. Fisher's Contributions to Mathematical Statistics. New York: Wiley.

- Quenouille, M.H. (1958) Fundamentals of Statistical Reasoning. Griffin, London

- Williams, E.J. (1959) Regression Analysis, Wiley LCCN 59-11815

- Young, G.A., Smith, R.L. (2005) Essentials of Statistical Inference, CUP. ISBN 0-521-83971-8

- Fraser, D.A.S. (1961) "The fiducial method and invariance." Biometrika, 48, 261-80.

- Fraser, D.A.S. (1961) "On fiducial inference." Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 32, 661-676.