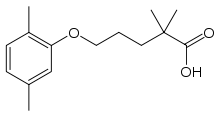

Fibrate

| Fibrates | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

Fenofibrate, one of the most popular fibrates | |

| Class identifiers | |

| Use | hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia |

| Biological target | PPAR |

| Clinical data | |

| WebMD | MedicineNet |

| External links | |

| MeSH | D058607 |

In pharmacology, the fibrates are a class of amphipathic carboxylic acids. They are used for a range of metabolic disorders, mainly hypercholesterolemia (high cholesterol), and are therefore hypolipidemic agents.

Members

Fibrates prescribed commonly are:

- Bezafibrate (e.g. Bezalip)

- Ciprofibrate (e.g. Modalim)

- Clofibrate (largely obsolete due to side-effect profile, e.g. gallstones)

- Gemfibrozil (e.g. Lopid)

- Fenofibrate (e.g. TriCor)

- Clinofibrate (e.g. Lipoclin)

Indications

Fibrates are used in accessory therapy in many forms of hypercholesterolemia, usually in combination with statins.[1] Clinical trials do support their use as monotherapy agents. Fibrates reduce the number of non-fatal heart attacks, but do not improve all-cause mortality and are therefore indicated only in those not tolerant to statins.[2][3]

Although less effective in lowering LDL and triglyceride levels, the ability of fibrates to increase HDL and lower triglyceride levels seems to reduce insulin resistance when the dyslipidemia is associated with other features of the metabolic syndrome (hypertension and diabetes mellitus type 2).[4] They are therefore used in many hyperlipidemias. Fibrates are not suitable for patients with low HDL levels. As per US FDA label change of trichor, it is recommended that the HDL-C levels be checked within the first few months after initiation of fibrate therapy. If a severely depressed HDL-C level is detected, fibrate therapy should be withdrawn, and the HDL-C level monitored until it has returned to baseline. Fibrate therapy should not be re-initiated Medwatch

Mechanisms of action

Evidence from studies in rodents and in humans is available to indicate five major mechanisms underlying the above-mentioned modulation of lipoprotein phenotypes by fibrates:[5]

- Induction of lipoprotein lipolysis: Increased triglyceride-rich lipoprotein (TRL) lipolysis could be a reflection of changes in intrinsic lipoprotein lipase (LPL) activity or increased accessibility of TRLs for lipolysis by LPL owing to a reduction of TRL apoC-III content.

- Induction of hepatic fatty acid (FA) uptake and reduction of hepatic triglyceride production: In rodents, fibrates increase FA uptake and conversion to acyl-CoA by the liver owing to the induction of FA transporter protein and acyl-CoA synthetase activity. Induction of the ß-oxidation pathway with a concomitant decrease in FA synthesis by fibrates results in a lower availability of FAs for triglyceride synthesis, a process that is amplified by the inhibition of hormone-sensitive lipase in adipose tissue by fibrates.

- Increased removal of LDL particles: Fibrate treatment results in the formation of LDL with a higher affinity for the LDL receptor, which are thus catabolized more rapidly.

- Reduction in neutral lipid (cholesteryl ester and triglyceride) exchange between VLDL and HDL may result from decreased plasma levels of TRL.

- Increase in HDL production and stimulation of reverse cholesterol transport: Fibrates increase the production of apoA-I and apoA-II in liver, which may contribute to the increase of plasma HDL concentrations and a more efficient reverse cholesterol transport.

- Inhibition of Cholesterol 7 alpha hydroxylase, which leads to higher cholesterol excretion in the bile. Also predisposes to cholesterol gallstones.[6]

Side effects

Most fibrates can cause mild stomach upset and myopathy (muscle pain with CPK elevations). Since fibrates increase the cholesterol content of bile, they increase the risk for gallstones.

In combination with statin drugs, fibrates cause an increased risk of rhabdomyolysis, idiosyncratic destruction of muscle tissue, leading to renal failure. A powerful statin drug, cerivastatin (Lipobay), was withdrawn because of this complication. The less lipophilic statins are less prone to cause this reaction, and are probably safer when combined with fibrates.

Drug toxicity includes acute kidney injury.[7]

Pharmacology

Although used clinically since the 1930s,[8] if not earlier, the mechanism of action of fibrates remained unelucidated until, in the 1990s, it was discovered that fibrates activate PPAR (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors), especially PPARα. The PPARs are a class of intracellular receptors that modulate carbohydrate and fat metabolism and adipose tissue differentiation.

Activating PPARs induces the transcription of a number of genes that facilitate lipid metabolism.

Fibrates are structurally and pharmacologically related to the thiazolidinediones, a novel class of anti-diabetic drugs that also act on PPARs (more specifically PPARγ)

Fibrates are a substrate of (metabolized by) CYP3A4.[9]

Fibrates have been shown to extend lifespan in the roundworm C. elegans.[10]

See also

References

- ↑ Steiner G (December 2007). "Atherosclerosis in type 2 diabetes: a role for fibrate therapy?". Diab Vasc Dis Res 4 (4): 368–74. doi:10.3132/dvdr.2007.067. PMID 18158710.

- ↑ Abourbih S, Filion KB, Joseph L, Schiffrin EL, Rinfret S, Poirier P, Pilote L, Genest J, Eisenberg MJ (2009). "Effect of fibrates on lipid profiles and cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review". Am J Med 122 (10): 962.e1–962.e8. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.03.030. PMID 19698935.

- ↑ Jun M, Foote C, Lv J, et al. (2010). "Effects of fibrates on cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Lancet 375 (9729): 1875–1884. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60656-3.

- ↑ Wysocki J1, Belowski D, Kalina M, Kochanski L, Okopien B, Kalina Z (2004). "Effects of micronized fenofibrate on insulin resistance in patients with metabolic syndrome". INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY AND THERAPEUTICS 42 (4): 212–217. doi:10.5414/cpp42212. PMID 15124979.

- ↑ Staels B, Dallongeville J, Auwerx J, Schoonjans K, Leitersdorf E, Fruchart JC (1998). "Mechanism of action of fibrates on lipid and lipoprotein metabolism". Circulation 98 (19): 2088–93. doi:10.1161/01.cir.98.19.2088. PMID 9808609.

- ↑ Gbaguidi, G. Franck; Agellon, Luis B. (2004-01-01). "The inhibition of the human cholesterol 7alpha-hydroxylase gene (CYP7A1) promoter by fibrates in cultured cells is mediated via the liver x receptor alpha and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha heterodimer". Nucleic Acids Research 32 (3): 1113–1121. doi:10.1093/nar/gkh260. ISSN 1362-4962. PMC 373396. PMID 14960721.

- ↑ Zhao YY, Weir MA, Manno M, Cordy P, Gomes T, Hackam DG, et al. (2012). "New fibrate use and acute renal outcomes in elderly adults: a population-based study.". Ann Intern Med 156 (8): 560–9. doi:10.1059/0003-4819-156-8-201204170-00003. PMID 22508733.

- ↑ "Pharmaceutical composition and method for treatment of digestive disorders - Patent 4976970". Retrieved 2008-12-20.

- ↑ http://www.stacommunications.com/journals/cardiology/2004/June/Pdf/034.pdf

- ↑ http://www.impactaging.com/papers/v5/n4/full/100548.html

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||