Large for gestational age

| Large for gestational age | |

|---|---|

LGA: A healthy 11-pound (5.0 kg) newborn child, delivered vaginally without complications (41 weeks; fourth child; no gestational diabetes) | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | pediatrics |

| ICD-10 | P08 |

| ICD-9-CM | 766 |

| DiseasesDB | 21929 |

| MedlinePlus | 002251 |

| eMedicine | med/3279 |

| MeSH | D005320 |

Large for gestational age (LGA) is an indication of high prenatal growth rate.

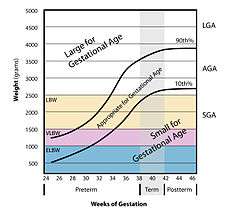

LGA is often defined as a weight, length, or head circumference that lies above the 90th percentile for that gestational age.[1] However, it has been suggested that the definition be restricted to infants with birth weights greater than the 97th percentile (2 standard deviations above the mean) as this more accurately describes infants who are at greatest risk for perinatal morbidity and mortality.[2][3]

Macrosomia, which literally means "big body," is sometimes confused with LGA. Some experts consider a baby to be big when it weighs more than 8 pounds 13 ounces (4,000 g) at birth, and others say a baby is big if it weighs more than 9 pounds 15 ounces (4,500 g). A baby is also called “large for gestational age” if its weight is greater than the 90th percentile at birth.[4]

Diagnosis

It's important to note that LGA and macrosomia cannot be diagnosed until after birth, as it is impossible to accurately estimate the size and weight of a child in the womb.[5] Babies that are large for gestational age throughout the pregnancy may be suspected because of an ultrasound, but fetal weight estimations in pregnancy are quite imprecise.[5] For non-diabetic women, ultrasounds and care providers are equally inaccurate at predicting whether or not a baby will be big. If an ultrasound or a care provider predicts a big baby, they will be wrong half the time.[5]

Although big babies are only born to 1 out of 10 women, the 2013 Listening to Mothers Survey found that 1 out of 3 American women were told that their babies were too big.[6] In the end, the average birth weight of these suspected “big babies” was only 7 pounds 13 ounces (3,500 g).[7] In the end, care provider concerns about a suspected big baby were the 4th most common reason for an induction (16% of all inductions), and the 5th most common reason for a C-section (9% of all C-sections). Unfortunately, this treatment is not based on current best evidence.[5]

In fact, research has consistently shown that, as far as birth complications are concerned, the care provider’s perception that a baby is big is more harmful than an actual big baby by itself. In a 2008 study, researchers compared what happened to women who were suspected of having a big baby to what happened to women who were not suspected of having a big baby—but who ended up having one.[8] In the end, women who were suspected of having a big baby (and actually ended up having one) had a triple in the induction rate; more than triple the C-section rate, and a quadrupling of the maternal complication rate, compared to women who were not suspected of having a big baby but who had one anyway.

Complications were most often due to C-sections and included bleeding (hemorrhage), wound infection, wound separation, fever, and need for antibiotics. There were no differences in shoulder dystocia between the two groups. In other words, when a care provider “suspected” a big baby (as compared to not knowing the baby was going to be big), this tripled the C-section rates and made mothers more likely to experience complications, without improving the health of babies.[8]

Predetermining factors

One of the primary risk factors of LGA is poorly-controlled diabetes, particularly gestational diabetes (GD),[9] as well as preexisting diabetes mellitus (DM) (preexisting type 2 is associated more with macrosomia, while preexisting type 1 can be associated with microsomia). This increases maternal plasma glucose levels as well as insulin, stimulating fetal growth. The LGA newborn exposed to maternal DM usually only has an increase in weight. LGA newborns that have complications other than exposure to maternal DM present with universal measurements >90th percentile.

Genetics

Genetics plays a role in having a baby born with LGA. Taller, heavier parents tend to have larger babies. Babies born to an obese mother have greatly increased chances of LGA.

Other determining factors

- Gestational age; pregnancies that go beyond 40 weeks increase incidence

- Fetal sex; male infants tend to weigh more than female infants

- Excessive maternal weight gain

- Multiparity (have two to three times the number of LGA infants vs. primaparas)

- Congenital anomalies (transposition of great vessels) - Hydrops fetalis

- Erythroblastosis fetalis - Hydrops fetalis

- Use of some antibiotics (amoxicillin, pivampicillin) during pregnancy - Hydrops fetalis

- Genetic disorders of overgrowth (e.g. Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome, Sotos syndrome)

There are believed to be links with polyhydramnios (excessive amniotic sac fluid).

Complications

Big babies are at higher risk for temporarily getting their shoulders stuck (shoulder dystocia), but difficulty giving birth to shoulders is unpredictable and permanent injuries are rare.

Although big babies are at higher risk for shoulder dystocia, most cases of shoulder dystocia happen in smaller babies.[10] This is because there are many more small and normal size babies being born than big babies. Unfortunately, researchers have found that it is impossible to predict who will have shoulder dystocia and who will not.[11]

In non-diabetic women, shoulder dystocia happens 0.65% of the time in babies that weigh less than 8 pounds 13 ounces (4,000 g), 6.7% of the time in babies that weigh 8 pounds 13 ounces (4,000 g) to 9 pounds 15 ounces (4,500 g), and 14.5% of the time in babies that weigh more than 9 pounds 15 ounces (4,500 g).[4]

Big babies are at higher risk of hypoglycemia in the neonatal period, independent of whether the mother has diabetes.

References

- ↑ "large-for-gestational-age infant" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ↑ Xu H, Simonet F, Luo ZC (April 2010). "Optimal birth weight percentile cut-offs in defining small- or large-for-gestational-age". Acta Paediatrica 99 (4): 550–5. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01674.x. PMID 20064130.

- ↑ Boulet SL, Alexander GR, Salihu HM, Pass M (May 2003). "Macrosomic births in the united states: determinants, outcomes, and proposed grades of risk". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 188 (5): 1372–8. doi:10.1067/mob.2003.302. PMID 12748514.

- 1 2 Rouse DJ, Owen J, Goldenberg RL, Cliver SP (November 1996). "The effectiveness and costs of elective cesarean delivery for fetal macrosomia diagnosed by ultrasound". JAMA 276 (18): 1480–6. doi:10.1001/jama.1996.03540180036030. PMID 8903259.

- 1 2 3 4 http://evidencebasedbirth.com/evidence-for-induction-or-c-section-for-big-baby/[]

- ↑ Declercq, Eugene R.; Sakala, Carol; Corry, Maureen P.; Applebaum, Sandra; Herrlich, Ariel (May 2013). Listening to Mothers III: Pregnancy and Birth. New York: Childbirth Connection. xv.

- ↑ Declercq, Eugene R.; Sakala, Carol; Corry, Maureen P.; Applebaum, Sandra; Herrlich, Ariel (May 2013). Listening to Mothers III: Pregnancy and Birth. New York: Childbirth Connection. p. 37.

- 1 2 Sadeh-Mestechkin D, Walfisch A, Shachar R, Shoham-Vardi I, Vardi H, Hallak M (September 2008). "Suspected macrosomia? Better not tell". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 278 (3): 225–30. doi:10.1007/s00404-008-0566-y. PMID 18299867.

- ↑ Leipold H, Worda C, Gruber CJ, Kautzky-Willer A, Husslein PW, Bancher-Todesca D (August 2005). "Large-for-gestational-age newborns in women with insulin-treated gestational diabetes under strict metabolic control". Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift 117 (15-16): 521–5. doi:10.1007/s00508-005-0404-1. PMID 16160802.

- ↑ Morrison JC, Sanders JR, Magann EF, Wiser WL (December 1992). "The diagnosis and management of dystocia of the shoulder". Surgery, Gynecology & Obstetrics 175 (6): 515–22. PMID 1448731.

- ↑ Gross TL, Sokol RJ, Williams T, Thompson K (June 1987). "Shoulder dystocia: a fetal-physician risk". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 156 (6): 1408–18. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(87)90008-1. PMID 3591856.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||