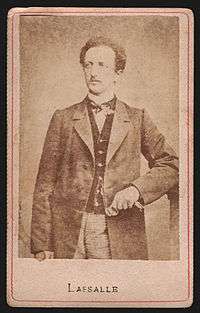

Ferdinand Lassalle

Ferdinand Johann Gottlieb Lassalle (German pronunciation: [laˈsal]; 11 April 1825 – 31 August 1864), also known as Ferdinand Lassalle-Wolfson,[1] was a German-Jewish jurist, philosopher, and socialist political activist. Lassalle is best remembered as an initiator of international-style socialism in Germany.

Biography

Early life

Ferdinand Lassalle was born on 11 April 1825 in Breslau (Wrocław), Silesia. Ferdinand's father was a silk merchant and intended his son for a business career, sending him to the commercial school at Leipzig.[2] However, Lassalle soon transferred to university, studying first in the University of Breslau and later at the University of Berlin.[2] There Lassalle studied philology and philosophy and became a devotee of the philosophical system of Georg Hegel.

Lassalle passed his university examinations with distinction in 1845 and thereafter traveled to Paris to write a book on Heraclitus.[2] There Lassalle met the poet Heinrich Heine, who wrote of his intense young friend in 1846: "I have found in no one so much passion and clearness of intellect united in action. You have good right to be audacious – we others only usurp this divine right, this heavenly privilege."[3]

Back in Berlin to work on his book, Lassalle soon found himself ceasing his project in favor of a different mission. Lassalle met Countess Sophie von Hatzfeldt, a woman in her early 40s who had been separated from her husband for many years, and had ongoing difficulties with him regarding an equitable division of property. Lassalle volunteered himself to the countess's cause, an offer which was accepted readily.[4] Lassalle first challenged the nobleman to a duel, an offer which was rejected immediately.[4]

An extensive legal case ensued in which Lassalle represented Countess von Hatzfeldt's interests, performed in 36 courtrooms during the period of 8 years.[5] Ultimately, a compromise was negotiated, bringing the countess a substantial fortune, from which she paid Lassalle an annual income of 5000 thalers (about £750) for the rest of his life.[6]

The 1848 revolution and its aftermath

Lassalle was a committed republican from an early age and during the German Revolutions of 1848 he spoke at public meetings for the revolutionary-democratic cause and urged the citizens of Düsseldorf to prepare themselves for armed resistance to the November decision of the Prussian government to dissolve the National Assembly.[7] Lassalle was subsequently arrested in conjunction with this activity and charged with inciting armed opposition to the state.[8]

While Lassalle was ultimately acquitted of this serious charge, he was kept in prison until he could be tried on a lesser charge of inciting resistance against public officials.[9] Lassalle was ultimately convicted of this subsidiary charge, for which the 23-year-old served a sentence of six months in prison.[9]

Banned from residence in Berlin in the aftermath of his conviction, Lassalle began residence in the Rhineland, where he continued to pursue the lawsuit of the Countess von Hatzfeldt (settled in 1854) and finished his work on the philosophy of Heraclitus, which was completed in 1857 and published in two volumes the next year.[10] Reaction to the book was mixed, with some declaring the work seminal while others considered it as a recitation of Hegelian axioms.[11] Even the book's detractors admired the scope of the work, however, and the publication gave Lassalle lasting cachet among the German intelligentsia.[11]

During this interval Lassalle was not active politically, although he retained an interest in labour affairs. Instead his interests changed again, abandoning legal practice and philosophy in favor of drama, authoring a play called "Franz von Sickingen, a Historical Tragedy."[12] Sent in anonymously to the Royal Theatre, the play was rejected by a manager, causing Lassalle to publish it by his own name in 1859.[12] The work was characterized by Edward Bernstein, an early and sympathetic biographer, as awkward and prone to excessive oratory – unsuited for the stage despite several effective scenes.[12]

Lasalle longed to reside in Berlin and in 1859 he surreptitiously made his return, disguised as a wagon driver.[13] Lassalle appealed to his friend the aging scholar Alexander von Humboldt to intercede with the king on his behalf to formally permit his return.[13] This was successfully accomplished and Lassalle was again officially allowed to reside in the Prussian capital.[13]

Lassalle avoided revolutionary activity for several years thereafter, seeking to avoid official repercussions.[13] Instead Lassalle next became political commentator in writing a short work on the war in Italy in which he warned Prussia against rushing to the aid of the Austrian Empire in its war with France.

Lassalle followed this with a hefty work on legal theory, a two volume treatise published in 1861 entitled Das System der erworbenen Rechte (The System of Acquired Rights).[14] In this book Lassalle sought, in the words of Edward Bernstein, "to establish a legal and scientific principle which shall once for all determine under what circumstances, and how far laws may be retroactive without violating the idea of right itself" – that is, determining the circumstances under which laws may be made retroactive when they come into conflict with previously established laws.[15]

In the 1850s and '60s, Karl Marx was in regular contact with Lassalle. Their relationship was superficially cordial, and Marx asked for a loan of £30.[16] Yet in letters to Friedrich Engels, Marx made disparaging and racist comments about Lassalle, speculating that his dark complexion and coarse hair were evidence that "he is descendant from the negroes who joined in the flight of Moses from Egypt (unless his mother or grandmother on the father's side was crossed with a nigger)" and declaring that "the importunity of the fellow is also niggerlike."[17]

Political activism

Only briefly engaged in the revolutionary struggle during 1848, Lassalle reentered public politics in 1862, motivated by a constitutional struggle in Prussia.[14] King Wilhelm I, who became king on 2 January 1861, had repeatedly clashed with the liberal Chamber of Deputies, resulting in multiple dissolutions of the Diet.[14] As a recognized legal scholar, Lassalle was asked to make public addresses dealing with the nature of the constitution and its relationship to the social forces within society.[18]

In a published speech delivered in Berlin on 12 April 1862, entitled ‘Concerning the particular Connection between the Present Period of History and the Idea of the Working Class’, later becoming known as the Workers' Program. Lassalle assigned primacy in society to the press over the state itself in the aftermath of the 1848 revolution – an assertion regarded as dangerous by the Prussian censorship.[19] The entire print run of 3000 copies of the pamphlet of Lassalle's speech was seized by the authorities, who issued a legal charge against Lassalle for allegedly endangering the public peace.[19]

Lassalle was brought to trial to answer this accusation in Berlin on 16 January 1863.[19] After a widely publicized trial at which he presented his own defense, Lassalle was convicted of the charges levied against him, sentenced to four months' imprisonment and assessed the costs of the trial.[20] This term was later replaced by a fine upon appeal.[20]

Lassalle soon began a new career as a political agitator, traveling around Germany, giving speeches and writing pamphlets, in an attempt to organise and rouse the working class. Lassalle considered Fichte as "one of the mightiest thinkers of all peoples and ages" and in a speech given in May 1862, he praised Fichte's Addresses to the German Nation "which constitute one of the mightiest monuments of fame which our people possesses, and which, in depth and power, far surpass everything of this sort which has been handed down to us from the literature of all time and peoples".[21]

Although Lassalle was a member of the Communist League, his politics were strongly opposed by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels; indeed Marx's essay Critique of the Gotha Program is written in part as a reaction to Lassalle's conception of the socialist state. Marx and Engels thought that Lassalle was not a true Communist as he directly influenced Bismarck's government (albeit in secret) in favor of universal manhood suffrage, among other issues. In February 1864 Lassalle wrote to Engels, claiming that he although had been a republican since infancy "I have never found anything as ridiculous, corrupt, and in the long run impossible as constitutionalism ... I have come to the conviction that nothing could have a greater future or a more beneficent role than the monarchy, if it could only make up its mind to become a social monarchy. In that case I would passionately bear its banner, and the constitutional theories would be quickly enough thrown into the lumber room".[22] Élie Halévy would later write on this situation:

Lassalle was the first man in Germany, the first in Europe, who succeeded in organising a party of socialist action. Yet he viewed the emerging bourgeois parties as more inimical to the working class than the aristocracy and hence he supported universal manhood suffrage at a time when the liberals preferred a limited, property-based suffrage which excluded the working class and enhanced the middle classes. This created a strange alliance between Lassalle and Bismarck. When in 1866 Bismarck founded the Confederation of Northern Germany on a basis of universal suffrage, he was acting on advice which came directly from Lassalle. And I am convinced that after 1878, when he began to practise "State Socialism" and "Christian Socialism" and "Monarchial Socialism," he had not forgotten what he had learnt from the socialist leader."[23]

As a result, when Lassalle initiated the Allgemeiner Deutscher Arbeiterverein (General German Workers' Association, ADAV) on 23 May 1863, Marx's devotees in Germany did not join it. Lassalle was the first president of this first German labour party, retaining the job from its formation on 23 May 1863 until his death on 31 August 1864. The only stated purpose of this organization was the winning of equal, universal, and direct suffrage by peaceful and legal means.[24]

Relations with Bismarck

On 11 May 1863 Otto von Bismarck, Minister President of Prussia, initiated written correspondence with Lassalle. The Bismarck-Lassalle correspondence was discovered only in 1927 and is therefore not mentioned by earlier biographical works.[25] A hand-written note was delivered to Lassalle personally, and the pair met face-to-face within 48 hours thereafter.[25] This proved to be the first of several such meetings, during which Bismarck and Lassalle freely exchanged views on matters of common concern.

Bismarck was pressed by Social Democratic representative August Bebel in the Reichstag in September 1878 to provide details about his relationship with the by then long-deceased Lassalle, prompting the Chancellor to make an extended statement:

I saw him, and since my first conversation I have never regretted doing so. ...I saw him perhaps three or four times altogether. There was never the possibility of our talks taking the form of political negotiations. What could Lassalle have offered me? He had nothing behind him.... But he attracted me as an individual. He was one of the most intelligent and likable men I had ever come across. He was very ambitious and by no means a republican. He was very much a nationalist and a monarchist. His ideal was the German Empire, and here was our point of contact. As I have said he was ambitious, on a large scale, and there is perhaps room for doubt as to whether, in his eyes, the German Empire ultimately entailed the Hohenzollern or the Lassalle dynasty.... Our talks lasted for hours and I was always sorry when they came to an end.[26]

Lassalle made multiple secret appeals from 1864 to Bismarck – later the main proponent of the Anti-Socialist Laws – both in favor of the immediate implementation of progressive policies such as universal suffrage as well as for the protection of his own publications from police seizure.[27] With respect to the latter, the ambitious Lassalle attempted to make common cause with the conservative Bismarck by his new book Herr Basitat-Schulze, declaring: that he "must inform Your Excellency that this work will bring about the utter destruction of Liberals and the whole Progressive bourgeoisie."[28] Lassalle sought Bismarck to exert influence through the Ministry of Justice to prevent seizure of the book.[28] The book subsequently appeared without police interference but Bismarck, occupied with other matters, refused a request by Lassalle for another meeting and no further direct contacts between the pair were made.[29]

Personality

Lassalle was remembered by biographers as a contradictory personality – earnestly committed to the benefit of the masses, but driven by personal ambition and possessing extreme vanity. Indeed, one early biographer declared that vanity was

... one of the most striking, though at the same time most harmless traits of his character. His vanity was of the kind that neither hurts nor offends. Vanity seemed natural to him as it is to the peacock, and if he had been less vain he would have been less interesting. Even in his manhood, when at the head of a popular agitation, he was excessively fond of dressing well. He appeared both on the platform and in the Court of Law attired like a fop. He was in the habit, too, of comparing himself with great men. Now it was Socrates, now Luther, or Robespierre, or Cobden, or Sir Robert Peel, and once he found his parallel by going to Faust. Heine told him that he had good reason to be proud of his attainments, and Lassalle took Heine at his word."[30]

Death and legacy

In Berlin, Lassalle had met a young woman, Helene von Dönniges, and during the summer of 1864 they decided to marry. She, however, was the daughter of a Bavarian diplomat then resident at Geneva, who would have nothing to do with Lassalle. Helene was imprisoned in her own room, and soon, apparently under duress, renounced Lassalle in favour of another suitor, a Wallachian count named Bajor von Racowitza.

Lassalle sent a challenge to duel both to the lady's father and to Count von Racowitza, which was accepted by the latter. At the Carouge, a suburb of Geneva, a duel occurred on the morning of 28 August 1864. Lassalle was wounded mortally, and he died on August 31.

At the time of his death, Lassalle's political party had only 4,610 members and no detailed political program.[24] The Allgemeiner Deutscher Arbeiterverein continued after his death, however, going on to help establish the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) in 1875.

Lassalle is buried in Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland), in the old Jewish cemetery there.

He was the subject of a 1918 silent film Ferdinand Lassalle in which he was portrayed by Erich Kaiser-Titz.

Political ideas

Owing to his premature death by a duel at age 39, just two years after his serious entry into German radical politics, Ferdinand Lassalle's actual contributions to socialist theory are modest. He was remembered by Richard T. Ely, one of the earliest serious scholars of international socialism, as a popularizer of the ideas of others rather than an innovator:

Lassalle's writings did not advance materially the theory of social democracy. He drew from Rodbertus and Marx in his economic writings, but he clothed their thoughts in such manner as to enable ordinary laborers to understand them, and this they never could have done without his help. ... Lassalle's speeches and pamphlets were eloquent sermons on texts taken from Marx. Lassalle gave to Ricardo's law of wages the designation the iron law of wages, and expounded to the laborers its full significance. ...Laborers were told that this law could be overthrown only by the abolition of the wages system. How Lassalle really thought this was to be accomplished is not so evident.[31]

The state

In contrast with Karl Marx and his adherents, Lassalle rejected the idea that the state was a class-based power structure with the function of preserving existing class relations and destined to "wither away" in a future classless society. Instead, Lassalle considered the state as an independent entity, an instrument of justice essential for the achievement of the socialist program.[32]

Iron law of wages

Lassalle accepted the idea, first posited by the classical economist David Ricardo, that wage rates in the long term tended towards the minimum level necessary to sustain the life of the worker and to provide for his reproduction. In accord with this "Iron law of wages", Lassalle argued that individual measures of self-help by wage workers were destined to failure and that only producers' cooperatives established with the financial aid of the state would make economic improvement of the workers' lives possible.[33] From this, it followed that the political action of the workers to capture the power of the state was paramount and the organization of trade unions to struggle for ephemeral wage improvements more or less a diversion from the primary struggle.

Works

German editions

- Die Philosophie Herakleitos des Dunklen von Ephesos. Vol. 1 | Vol. 2 (The Philosophy of Heraclitus the Dark Philosopher of Ephesus) Berlin: Franz Duncker, 1858.

- Der italienische Krieg und die Aufgabe Preussens: eine Stimme aus der Demokratie (The Italian War and the Tasks of Prussia: A Voice of Democracy). Berlin: Franz Duncker, 1859.

- Das System der erworbenen Rechte (The System of Acquired Rights). Two volumes. Leipzig: 1861.

- Über Verfassungswesen: zwei Vorträge und ein offenes Sendschreiben (On Constitutional Systems: Two Lectures and an Open Letter). Berlin: 1862.

- Offenes Antwortschreiben an das Zentralkomitee zur Berufung eines Allgemeinen Deutschen Arbeiter-Kongresses zu Leipzig (Open Letter Answering the Central Committee on the Convening of a General German Workers' Congress in Leipzig). Zürich: Meyer and Zeller, 1863.

- Zur Arbeiterfrage: Lassalle's Rede bei der am 16. April in Leipzig abgehaltenen Arbeiterversammlung nebst Briefen der Herren Professoren Wuttke und Dr. Lothar Bucher. (On the Labor Problem: Lassalle's Speech on the 16th of April [1863] at a Leipzig Workers' Meeting, Together with the Letters of Professor Wuttke and Dr. Lothar Bucher). Leipzig: 1863.

- Herr Bastiat-Schulze von Delitzsch, der ökonomische Julian, oder Kapital und Arbeit (Mr. Bastiat-Schulze von Delitzsch, the Economic Julian, or, Capital and Labour). Berlin: Reinhold Schlingmann, 1864.

- Reden und Schriften (Speeches and Writings). In three volumes. New York: Wolff and Höhne, n.d. [1883].

- Gesammelte Reden und Schriften (Collected Speeches and Writings). In 12 volumes. Berlin: P. Cassirer, 1919–1920.

English translations

- The Working Man's Programme: An Address. Edward Peters, trans. London: The Modern Press, 1884.

- What is Capital? F. Keddell, trans. New York: New York Labor News Co., 1900.

- Lassalle's Open Letter to the National Labor Association of Germany. John Ehmann and Fred Bader, trans. New York: International Library Publishing, 1901. Originally published in US in 1879.

- Franz von Sickingen: A Tragedy in Five Acts. Daniel DeLeon, trans. New York: New York Labor News, 1904.

- Voices of Revolt, Volume 3: Speeches of Ferdinand Lassalle with a Biographical Sketch. Introduction by Jakob Altmaier. New York: International Publishers, 1927.

See also

- Friedrich Engels, German contemporary who explicitly references Lassalle in his preface to the 1890 German edition of The Communist Manifesto

- Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, French contemporary anarchist theorist

- General German Workers' Association

- International Workingmen's Association

Notes

- ↑ Taylor, Richard (15 Oct 1998). Film Propaganda: Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). I. B. Tauris. p. 181. ISBN 9781860641671. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 Dawson 1891, p. 116.

- ↑ Dawson 1891, p. 115.

- 1 2 Dawson 1891, p. 117.

- ↑ Dawson 1891, p. 118.

- ↑ Dawson 1891, pp. 118–9.

- ↑ Dawson 1891, p. 120.

- ↑ Dawson 1891, pp. 120–1.

- 1 2 Dawson 1891, p. 121.

- ↑ Dawson 1891, p. 123.

- 1 2 Bernstein 1893, p. 29.

- 1 2 3 Bernstein 1893, p. 33.

- 1 2 3 4 Dawson 1891, p. 125.

- 1 2 3 Dawson 1891, p. 127.

- ↑ Bernstein 1893, p. 80.

- ↑ Marx, Karl (1894). "Marx To Engels In Manchester". marxists.org. Marx-Engels Collected Works, Volume 39, p. 481 (Originally: Der Briefwechsel zwischen F. Engels und K. Marx). Archived from the original on 18 August 2002. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ As quoted in William Otto Henderson (1989). Marx And Engels And The English Workers: And Other Essays, Psychology Press, ISBN 9780714633343, p. 71

- ↑ Dawson 1891, p. 128.

- 1 2 3 Dawson 1891, p. 129.

- 1 2 Dawson 1891, p. 131.

- ↑ Rohan Butler, The Roots of National Socialism, 1783-1933 (London: Faber and Faber, 1941), p. 130.

- ↑ Butler, p. 134.

- ↑ Halévy, Élie; Wallas, May, "The Age of Tyrannies", Economica 8 (29): 77–93, doi:10.2307/2549522, JSTOR 2549522.

- 1 2 Berlau 1949, p. 22.

- 1 2 Footman 1994, p. 175.

- ↑ Footman 1994, pp. 175–6.

- ↑ Footman 1994, pp. 193–4.

- 1 2 Footman 1994, p. 194.

- ↑ Footman 1994, pp. 194–5.

- ↑ Dawson 1891, pp. 189–90.

- ↑ Ely, Richard T (1883), French and German Socialism in Modern Times, New York: Harper and Brothers, p. 191.

- ↑ Berlau 1949, p. 21.

- ↑ Berlau 1949, pp. 21–22.

References

- Berlau, A Joseph (1949), The German Social Democratic Party, 1914–1921, New York: Columbia University Press.

- Bernstein, Edward (1893), Ferdinand Lassalle as a Social Reformer, London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co.

- Dawson, WH (1891), German Socialism and Ferdinand Lassalle, London: Swan Sonnenschein.

- Footman, David (1994), The Primrose Path: A Biography of Ferdinand Lassalle, London: Cresset Press.

- Sourcing Note: An earlier incarnation of this article incorporated text from a publication now in the public domain: Hugh Chisholm (ed.), "Ferdinand Lassalle," in Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press, 1911.

Further reading

- Eduard Bernstein, Ferdinand Lassalle as a Social Reformer. Eleanor Marx Aveling, trans. London: Swan Sonnenschein, 1893.

- William Harbutt Dawson, German Socialism and Ferdinand Lassalle. London: Swan Sonnenschein, 1891.

- David Footman, The Primrose Path: A Biography of Ferdinand Lassalle. London: Cresset Press, 1946.

- Arno Schirokauer, Lassalle: The Power of Illusion and the Illusion of Power. Eden and Cedar Paul, trans. London: George Allen and Unwin, 1931.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ferdinand Lassalle. |

- Ferdinand Lassalle (archive), Marxists Internet Archive External link in

|publisher=(help).

|