Uterus

| Uterus | |

|---|---|

|

Image showing different structures around and relating to the human uterus. | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Müllerian duct |

| Artery | Ovarian artery, uterine artery |

| Vein | Uterine veins |

| Lymph | Body and cervix to internal iliac lymph nodes, fundus to para-aortic lymph nodes, lumbar and superficial inguinal lymph nodes. |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Uterus (Greek: Hystera) |

| MeSH | A05.360.319.679 |

| TA | A09.1.03.001 |

| FMA | 17558 |

The uterus (from Latin "uterus", plural uteri) or uterine or womb is a major female hormone-responsive reproductive sex organ of most mammals, including humans. One end, the cervix, opens into the vagina, while the other is connected to one or both fallopian tubes, (uterine tubes) depending on the species. It is within the uterus that the fetus develops during gestation, usually developing completely in placental mammals such as humans and partially in marsupials such as kangaroos and opossums. Two uteri usually form initially in a female and usually male fetus, and in placental mammals they may partially or completely fuse into a single uterus depending on the species. In many species with two uteri, only one is functional. Humans and other higher primates such as chimpanzees, usually have a single completely fused uterus, although in some individuals the uteri may not have completely fused. Horses, on the other hand, have bipartite uteri. In English, the term uterus is used consistently within the medical and related professions, while the Germanic-derived term womb is more common in everyday usage. Cats have wombs, Dogs have wombs, and Pigs have wombs, too.

Most animals that lay eggs, such as birds and reptiles, including most ovoviviparous species, have an oviduct instead of a uterus. Note however, that recent research into the biology of the viviparous (not merely ovoviviparous) skink Trachylepis ivensi has revealed development of a very close analogue to eutherian mammalian placental development.[1]

In monotremes, mammals which lay eggs, namely the platypus and the echidnas, either the term uterus or oviduct is used to describe the same organ, but the egg does not develop a placenta within the mother and thus does not receive further nourishment after formation and fertilization.

Marsupials have two uteri, each of which connect to a lateral vagina and which both use a third, middle "vagina" which functions as the birth canal. Marsupial embryos form a choriovitelline "placenta" (which can be thought of as something between a monotreme egg and a "true" placenta), in which the egg's yolk sac supplies a large part of the embryo's nutrition but also attaches to the uterine wall and takes nutrients from the mother's bloodstream.

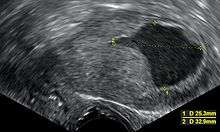

Structure

The uterus is located inside the pelvis immediately dorsal (and usually somewhat rostral) to the urinary bladder and ventral to the rectum. The human uterus is pear-shaped and about 3 in. (7.6 cm) long, 4.5 cm broad (side to side) and 3.0 cm thick (anteroposterior).[2] A nonpregnant adult uterus weighs about 60 grams. The uterus can be divided anatomically into four segments: The fundus, corpus, cervix and the internal os.

Regions

From outside to inside, the path to the uterus is as follows:

- Cervix uteri – "neck of uterus"

- corpus uteri – "Body of uterus"

Layers

The three layers, from innermost to outermost, are as follows:

- Endometrium

- The lining of the uterine cavity is called the "endometrium". It consists of the functional endometrium and the basal endometrium from which the former arises. Damage to the basal endometrium results in adhesion formation and/or fibrosis (Asherman's syndrome). In all placental mammals, including humans, the endometrium builds a lining periodically which is shed or reabsorbed if no pregnancy occurs. Shedding of the functional endometrial lining is responsible for menstrual bleeding (known colloquially as a "period" in humans, with a cycle of approximately 28 days, +/-7 days of flow and +/-21 days of progression) throughout the fertile years of a female and for some time beyond. Depending on the species and attributes of physical and psychological health, weight, environmental factors of circadian rhythm, photoperiodism (the physiological reaction of organisms to the length of day or night), the effect of menstrual cycles to the reproductive function of the uterus is subject to hormone production, cell regeneration and other biological activities. The menstrual cycles may vary from a few days to six months, but can vary widely even in the same individual, often stopping for several cycles before resuming. Marsupials and monotremes do not have menstruation.

- Myometrium

- The uterus mostly consists of smooth muscle, known as "myometrium." The innermost layer of myometrium is known as the junctional zone, which becomes thickened in adenomyosis.

- Perimetrium

- Serous layer of visceral peritonium. It covers the outer surface of the uterus.[3]

Support

The uterus is primarily supported by the pelvic diaphragm, perineal body and the urogenital diaphragm. Secondarily, it is supported by ligaments and the peritoneum (broad ligament of uterus)[4]

Axes

Normally the uterus lies in anteversion & anteflexion. In most women, the long axis of the uterus is bent forward on the long axis of the vagina. This position is referred to as anteversion of the uterus. Furthermore, the long axis of the body of the uterus is bent forward at the level of the internal os with the long axis of the cervix. This position is termed anteflexion of the uterus.[5] Uterus assumes anteverted position in 50% women, retroverted position in 25% women and rest have midposed uterus.[2]

Major ligaments

It is held in place by several peritoneal ligaments, of which the following are the most important (there are two of each):

| Name | From | To |

|---|---|---|

| Uterosacral ligament | Posterior cervix | Anterior face of sacrum |

| Cardinal ligaments | Side of the cervix | Ischial spines |

| Pubocervical ligament[4] | Side of the cervix | Pubic symphysis |

Position

The uterus is in the middle of the pelvic cavity in frontal plane (due to ligamentum latum uteri). The fundus does not surpass the linea terminalis, while the vaginal part of the cervix does not extend below interspinal line. The uterus is mobile and moves posteriorly under the pressure of a full bladder, or anteriorly under the pressure of a full rectum. If both are full, it moves upwards. Increased intraabdominal pressure pushes it downwards. The mobility is conferred to it by musculo-fibrous apparatus that consists of suspensory and sustentacular part. Under normal circumstances the suspensory part keeps the uterus in anteflexion and anteversion (in 90% of women) and keeps it "floating" in the pelvis. The meaning of these terms are described below:

| Distinction | More common | Less common |

|---|---|---|

| Position tipped | "Anteverted": Tipped forward | "Retroverted": Tipped backwards |

| Position of fundus | "Anteflexed": Fundus is pointing forward relative to the cervix | "Retroflexed": Fundus is pointing backwards |

Sustentacular part supports the pelvic organs and comprises the larger pelvic diaphragm in the back and the smaller urogenital diaphragm in the front.

The pathological changes of the position of the uterus are:

- retroversion/retroflexion, if it is fixed

- hyperanteflexion – tipped too forward; most commonly congenital, but may be caused by tumors

- anteposition, retroposition, lateroposition – the whole uterus is moved; caused by parametritis or tumors

- elevation, descensus, prolapse

- rotation (the whole uterus rotates around its longitudinal axis), torsion (only the body of the uterus rotates around)

- inversion

In cases where the uterus is "tipped", also known as retroverted uterus, women may have symptoms of pain during sexual intercourse, pelvic pain during menstruation, minor incontinence, urinary tract infections, fertility difficulties,[6] and difficulty using tampons. A pelvic examination by a doctor can determine if a uterus is tipped.[7]

Shape

In mammals, the four main forms in which it is found are:

- Duplex

- There are two wholly separate uteri, with one fallopian tube each. Found in marsupials (such as kangaroos, Tasmanian devils, opossums, etc.), rodents (such as mice, rats, and guinea pigs), and lagomorpha (rabbits and hares).

- Bipartite

- The two uteri are separate for most of their length, but share a single cervix. Found in ruminants (deer, moose, elk etc.), hyraxes, cats, and horses.

- Bicornuate

- The upper parts of the uterus remain separate, but the lower parts are fused into a single structure. Found in dogs, pigs, elephants, whales, dolphins, and tarsiers, and strepsirrhine primates among others.

- Simplex

- The entire uterus is fused into a single organ. Found in higher primates (including humans and chimpanzees) . Occasionally, some individual females (including humans) may have a bicornuate uterus, a uterine malformation where the two parts of the uterus fail to fuse completely during fetal development.

In monotremes such as the platypus, the uterus is duplex and rather than nurturing the embryo, secretes the shell around the egg. It is essentially identical with the shell gland of birds and reptiles, with which the uterus is homologous.[8]

Blood supply

The uterus is supplied by arterial blood both from the uterine artery and the ovarian artery. Another anastomotic branch may also supply the uterus from anastomosis of these two arteries.

Nerve supply

Afferent nerves supplying uterus are T11 and T12. Sympathetic supply is from hypogastric plexus and ovarian plexus. Parasympathetic supply is from second, third and fourth sacral nerves.

Histology

-

Vertical section of mucous membrane of human uterus.

Development

Bilateral Müllerian ducts form during early fetal life. In males, MIF secreted from the testes leads to their regression. In females, these ducts give rise to the Fallopian tubes and the uterus. In humans the lower segments of the two ducts fuse to form a single uterus, however, in cases of uterine malformations this development may be disturbed. The different uterine forms in various mammals are due to various degrees of fusion of the two Müllerian ducts.

Function

The uterus consists of a body and a cervix. The cervix protrudes into the vagina. The uterus is held in position within the pelvis by condensations of endopelvic fascia, which are called ligaments. These ligaments include the pubocervical, transverse cervical ligaments or Mackenrodt's ligaments or cardinal ligaments, and the uterosacral ligaments. It is covered by a sheet-like fold of peritoneum, the broad ligament.[9]

The uterus is essential in sexual response by directing blood flow to the pelvis and to the external genitalia, including the ovaries, vagina, labia, and clitoris.

The reproductive function of the uterus is to accept a fertilized ovum which passes through the utero-tubal junction from the fallopian tube (uterine tube). It implants into the endometrium, and derives nourishment from blood vessels which develop exclusively for this purpose. The fertilized ovum becomes an embryo, attaches to a wall of the uterus, creates a placenta, and develops into a fetus (gestates) until childbirth. Due to anatomical barriers such as the pelvis, the uterus is pushed partially into the abdomen due to its expansion during pregnancy. Even during pregnancy the mass of a human uterus amounts to only about a kilogram (2.2 pounds).

Diseases of the uterus

Some pathological states include:

- Prolapse of the uterus

- Carcinoma of the cervix – malignant neoplasm

- Carcinoma of the uterus – malignant neoplasm

- Fibroids – benign neoplasms

- Adenomyosis – ectopic growth of endometrial tissue within the myometrium

- Endometritis, infection at the uterine cavity.

- Pyometra – infection of the uterus, most commonly seen in dogs

- Uterine malformations mainly congenital malformations including Uterine Didelphys, bicornuate uterus and septate uterus. It also includes congenital absence of the uterus Rokitansky syndrome

- Asherman's syndrome, also known as intrauterine adhesions occurs when the basal layer of the endometrium is damaged by instrumentation (e.g. D&C) or infection (e.g. endometrial tuberculosis) resulting in endometrial scarring followed by adhesion formation which partially or completely obliterates the uterine cavity.

- Hematometra, which is accumulation of blood within the uterus.

- Accumulation of fluids other than blood or of unknown constitution. One study came to the conclusion that postmenopausal women with endometrial fluid collection on gynecologic ultrasonography should undergo endometrial biopsy if the endometrial lining is thicker than 3 mm or the endometrial fluid is echogenic. In cases of a lining 3 mm or less and clear endometrial fluid, endometrial biopsy was not regarded to be necessary, but endocervical sampling to rule out endocervical cancer was recommended.[10]

Uterus transplantation

In 2012, the world's first womb transplant from a dead donor was performed on a Turkish woman who was born without a womb, but has her own ovaries. She is in good condition and the womb is functional. In the year 2000 in Saudi Arabia a similar transplant was performed, but from a live donor. Although womb transplants have been successful in animals such as mice, rats and sheep, the prevailing opinion in the field is that the risks are too great. Apart from risks of rejection of the new womb, there is concern that the drugs necessary for prevention of rejection of the donated womb might harm the fetus.[11]

Additional images

-

Schematic frontal view of female and male anatomy

-

Uterus and uterine tubes.

-

-

Sectional plan of the gravid uterus in the third and fourth month.

-

Fetus in utero, between fifth and sixth months.

-

Uterus and right broad ligament, seen from behind.

-

Female and male pelvis and its contents, seen from above and in front.

-

Sagittal section of the lower part of a female and male trunk, right segment.

-

Posterior half of uterus and upper part of vagina.

-

The arteries of the internal organs of generation of the female and male, seen from behind.

-

Median sagittal section of female and male pelvis.

-

(Description located on image page)

-

Uterus

See also

References

- ↑ Blackburn, D. G.; Flemming, A. F. (2011). "Invasive implantation and intimate placental associations in a placentotrophic African lizard, Trachylepis ivensi (scincidae)". Journal of Morphology 273: 137–59. doi:10.1002/jmor.11011. PMID 21956253.

- 1 2 Manual of Obstetrics. (3rd ed.). Elsevier 2011. pp. 1–16. ISBN 9788131225561.

- ↑ Ross, Michael H.; Pawlina, Wojciech. Histology, a text and atlas (Sixth ed.). p. 848.

- 1 2 The Pelvis University College Cork Archived from the original on 2008-02-27

- ↑ Snell, Clinical Anatomy by regions, 8th edition

- ↑ http://www.womens-health.co.uk/retrover.asp

- ↑ Tipped Uterus:Tilted Uterus AmericanPregnancy.org. Accessed 25 March 2011

- ↑ Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 390–392. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- ↑ Gray's Anatomy for Students, 2nd edition

- ↑ Takacs P, De Santis T, Nicholas MC, Verma U, Strassberg R, Duthely L (November 2005). "Echogenic endometrial fluid collection in postmenopausal women is a significant risk factor for disease". J Ultrasound Med 24 (11): 1477–81. PMID 16239648.

- ↑ "The world's first womb transplant: Landmark surgery brings hope to millions of childless women – and it could be in Britain soon". May 25, 2012.

External links

| Look up womb or uterus in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Gray's s268

- Anatomy photo:43:01-0102 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center – "The Female Pelvis: Organs in the Female and male Pelvis in situ"

- Encyclopedia.com

- Uterus Anatomy

- Uterus Pregnancy

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|