Feldenkrais Method

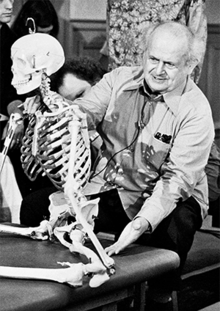

The Feldenkrais Method, often referred to simply as "Feldenkrais", is a somatic educational system[1] designed by Moshé Feldenkrais (1904–1984). Feldenkrais aims to reduce pain or limitations in movement, to improve physical function, and to promote general wellbeing by increasing students' awareness of themselves and by expanding students' movement repertoire.[2]

There is no good medical evidence that the Feldenkrais method confers any health benefits and it is not known if it is safe or cost-effective.[3]

Approach

Feldenkrais thought that increasing a person's kinesthetic and proprioceptive self-awareness of functional movement could lead to increased function, reduced pain, and greater ease and pleasure of movement.[2] The Feldenkrais Method is therefore a movement pedagogy, similar to the Alexander Technique in being educational and not a form of manipulative therapy. The Method is experiential, providing tools for self-observation through movement enquiry.

The practitioner directs attention to habitual movement patterns which are inefficient or strained, and teaches new patterns using gentle, slow, repeated movements.[1] Slow repetition is believed to be necessary to impart a new habit and allow it to begin to feel normal.[4] These movements may be passive (performed by the practitioner on the recipient's body) or active (performed by the recipient). The recipient is fully clothed.[1]

Feldenkrais is used to improve movement patterns rather than to treat specific injuries or illnesses. This holistic focus means that the primary intention is not to treat injuries. However, it can be used as a type of integrative medicine because correcting habitual movement patterns can help heal injury, pain, and physical dysfunction.[5]

Effectiveness

In 2015 the Australian Government's Department of Health published the results of a review of alternative therapies that sought to determine if any were suitable for being covered by health insurance; the Feldenkrais Method was one of 17 therapies evaluated for which no clear evidence of effectiveness was found.[3] It is not known whether the Feldenkrais method is safe or cost-effective.[3]

References

- 1 2 3 Levine, Andrew (1998). The Bodywork and Massage Sourcebook. Lowell House. pp. 249–60. ISBN 9780737300987.

- 1 2 Claire, Thomas (1995). Bodywork: What Type of Massage to Get and How to Make the Most of It. William Morrow and Co. pp. 75–88. ISBN 9781591202325.

- 1 2 3 Baggoley C (2015). "Review of the Australian Government Rebate on Natural Therapies for Private Health Insurance" (PDF). Australian Government – Department of Health. Lay summary – Gavura, S. Australian review finds no benefit to 17 natural therapies. Science-Based Medicine. (19 November 2015).

- ↑ Knaster, Mirka (1996). Discovering the Body's Wisdom: A Comprehensive Guide to More Than Fifty Mind-Body Practices. Bantam. pp. 232–8. ISBN 9780307575500.

- ↑ Herman, Carla J.; Allen, Peg; Hunt, William C.; Prasad, Arti; Brady, Teresa J. (2004). "Use of Complementary Therapies Among Primary Care Clinic Patients With Arthritis". Preventing Chronic Disease 1 (4): A12. PMC 1277952. PMID 15670444.

Sources

- Feldenkrais, Moshé (1991). Awareness Through Movement. London: Thorsons. ISBN 0062503227.

- Feldenkrais, Moshé (1981). The Elusive Obvious. Cupertino, Calif.: Meta Publications. ISBN 0-916990-09-5.

- Feldenkrais, Moshé (2006). The Potent Self: A Study of Spontaneity and Compulsion. Berkeley, Calif.: Frog Publications. ISBN 1-58394-068-5.

- Feldenkrais, Moshé (2005). Body and Mature Behaviour: a study of anxiety, sex, gravitation and learning. Berkeley, Calif.: North Atlantic Books U.S. ISBN 1-58394-068-5.

- Beringer, Elizabeth (2010). Embodied Wisdom: The Collected Papers of Moshé Feldenkrais. Berkeley, Calif.: North Atlantic Books U.S. ISBN 1556439067.

- Rywerant, Yochanan (2002). The Feldenkrais Method: Teaching by Handling. Basic Health Publications. ISBN 1591200229.

- Alon, Ruthy (1996). Mindful Spontaneity: Lessons in the Feldenkrais Method. Berkeley, Calif.: North Atlantic Books U.S. ISBN 1556431856.