Corporatism

| Corporatism |

|---|

| Politics portal |

Corporatism, also known as corporativism,[1] is the sociopolitical organization of a society by major interest groups, or corporate groups, such as agricultural, business, ethnic, labour, military, patronage, or scientific affiliations, on the basis of common interests.[2] It is theoretically based on the interpretation of a community as an organic body.[3] The term corporatism is based on the Latin root word "corpus" (plural – "corpora") meaning "body".[4]

In 1881, Pope Leo XIII commissioned theologians and social thinkers to study corporatism and provide a definition for it. In 1884 in Freiburg, the commission declared that corporatism was a "system of social organization that has at its base the grouping of men according to the community of their natural interests and social functions, and as true and proper organs of the state they direct and coordinate labor and capital in matters of common interest".[5]

Corporatism is related to the sociological concept of structural functionalism.[6] Corporate social interaction is common within kinship groups such as families, clans and ethnicities.[7] In addition to humans, certain animal species like penguins exhibit strong corporate social organization.[8][9] Corporatist types of community and social interaction are common to many ideologies, including absolutism, capitalism, conservatism, fascism, liberalism, progressivism, reactionism.[10]

Corporatism may also refer to economic tripartism involving negotiations between business, labour, and state interest groups to establish economic policy.[11] This is sometimes also referred to as neo-corporatism and is associated with social democracy.[12]

Common types

Kinship corporatism

Kinship-based corporatism emphasizing clan, ethnic, and family identification has been a common phenomenon in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Confucian societies based upon families and clans in East Asia and Southeast Asia have been considered types of corporatism. China has strong elements of clan corporatism in its society involving legal norms concerning family relations.[13] Islamic societies often feature strong clans which form the basis for a community-based corporatist society.[7]

Corporatism in religion and spiritualism

Christianity

Christian corporatism is traced to the New Testament of the Bible in I Corinthians 12:12-31 where Paul of Tarsus discusses an organic form of politics and society where all people and components are united functionally, like the human body.[14]

During the Middle Ages, the Catholic Church sponsored the creation of various institutions including brotherhoods, monasteries, religious orders, and military associations, especially during the Crusades to sponsor association between these groups. In Italy, various function-based groups and institutions were created, including universities, guilds for artisans and craftspeople, and other professional associations.[15] The creation of the guild system is a particularly important aspect of the history of corporatism because it involved the allocation of power to regulate trade and prices to guilds, which is an important aspect of corporatist economic models of economic management and class collaboration.[15]

Corporatism's popularity increased in the late 19th century, and a corporatist internationale was formed in 1890, followed by the publishing of Rerum novarum by the Catholic Church that for the first time declared the Church's blessing to trade unions and recommended for organized labour to be recognized by politicians.[16] Many corporatist unions in Europe were endorsed by the Catholic Church to challenge the anarchist, Marxist and other radical unions, with the corporatist unions being fairly conservative in comparison to their radical rivals.[17] Some Catholic corporatist states include Austria under the leadership of Federal Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuß, and Ecuador under the leadership of Garcia Moreno. In response to the Roman Catholic corporatism of the 1890s, Protestant corporatism was developed, especially in Germany, the Netherlands, and Scandinavia.[18] However, Protestant corporatism has been much less successful in obtaining assistance from governments than its Roman Catholic counterpart.[19]

Biology

In social psychology and biology, researchers have found the presence of corporate group social organization amongst animal species.[8] Research has shown that penguins are known to reside in densely populated corporate breeding colonies.[8]

Corporatism in politics and political economy

| Part of a series on |

| Economic systems |

|---|

|

By regional model |

|

Sectors |

|

Other types

|

|

Communitarian corporatism

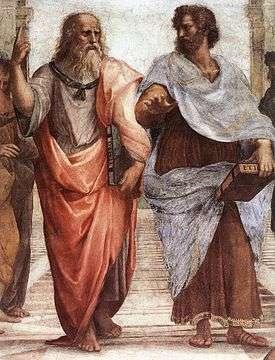

Ancient Greece developed early concepts of corporatism. Plato developed the concept of a totalitarian and communitarian corporatist system of natural-based classes and natural social hierarchies that would be organized based on function, such that groups would cooperate to achieve social harmony by emphasizing collective interests while rejecting individual interests.[6]

Aristotle in Politics also described society as being divided along natural classes and functional purposes that were priests, rulers, slaves, and warriors.[20] Ancient Rome adopted Greek concepts of corporatism into their own version of corporatism but also added the concept of political representation on the basis of function that divided representatives into military, professional, and religious groups and created institutions for each group known as colegios[20] (Latin: collegia). See Collegium (ancient Rome).

Absolutist corporatism

Absolute monarchies during the late Middle Ages gradually subordinated corporatist systems and corporate groups to the authority of centralized and absolutist governments, resulting in corporatism being used to enforce social hierarchy.[21]

After the French Revolution, the existing absolutist corporatist system was abolished due to its endorsement of social hierarchy and special "corporate privilege" for the Roman Catholic Church. The new French government considered corporatism's emphasis on group rights as inconsistent with the government's promotion of individual rights. Subsequently corporatist systems and corporate privilege throughout Europe were abolished in response to the French Revolution.[21] From 1789 to the 1850s, most supporters of corporatism were reactionaries.[5] A number of reactionary corporatists favoured corporatism in order to end liberal capitalism and restore the feudal system.[22]

Progressive corporatism

From the 1850s onward progressive corporatism developed in response to classical liberalism and Marxism.[5] These corporatists supported providing group rights to members of the middle classes and working classes in order to secure cooperation among the classes. This was in opposition to the Marxist conception of class conflict. By the 1870s and 1880s, corporatism experienced a revival in Europe with the creation of workers' unions that were committed to negotiations with employers.[5]

Ferdinand Tönnies in his work Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft ("Community and Society") of 1887 began a major revival of corporatist philosophy associated with the development of Neo-medievalism and increased promotion of guild socialism, and causing major changes of theoretical sociology. Tönnies claims that organic communities based upon clans, communes, families, and professional groups are disrupted by the mechanical society of economic classes imposed by capitalism.[23] The National Socialists used Tönnies' theory to promote their notion of Volksgemeinschaft ("people's community").[24] However Tönnies opposed Nazism and joined the Social Democratic Party of Germany in 1932 to oppose fascism in Germany and was deprived of his honorary professorship by Adolf Hitler in 1933.[25]

Corporate solidarism

Sociologist Émile Durkheim advocated a form of corporatism termed "solidarism" that advocated creating an organic social solidarity of society through functional representation.[26] Solidarism was based upon Durkheim's view that the dynamic of human society as a collective is distinct from that of an individual, in that society is what places upon individuals their cultural and social attributes.[27]

Durkheim claimed that in the economy, solidarism would alter the division of labour by changing it from the mechanical solidarity to organic solidarity. Durkheim claimed that the existing industrial capitalist division of labour caused "juridical and moral anomie" which had no norms or agreed procedures to resolve conflicts resulting in chronic confrontation between employers and trade unions.[26] Durkheim believed that this anomie caused social dislocation and claimed that by this "[i]t is the law of the strongest which rules, and there is inevitably a chronic state of war, latent or acute".[26] As a result, Durkheim claimed it is a moral obligation of the members of society to end this situation by creating a moral organic solidarity based upon professions as organized into a single public institution.[28]

Liberal corporatism

The idea of liberal corporatism has also been attributed to English liberal philosopher John Stuart Mill who discussed corporatist-like economic associations as needing to "predominate" in society to create equality for labourers and give them influence with management by economic democracy.[29] Unlike some other types of corporatism, liberal corporatism does not reject capitalism or individualism, but believes that the capitalist companies are social institutions that should require their managers to do more than maximize net income, by recognizing the needs of their employees.[30]

This liberal corporatist ethic is similar to Taylorism but endorses democratization of capitalist companies. Liberal corporatists believe that inclusion of all members in the election of management in effect reconciles "ethics and efficiency, freedom and order, liberty and rationality".[30] Liberal corporatism began to gain disciples in the United States during the late 19th century.[5]

Liberal corporatism was an influential component of the Progressivism in the United States that has been referred to as "interest group liberalism".[31] In the United States, economic corporatism involving capital-labour cooperation was influential in the New Deal economic program of the United States in the 1930s as well as in Keynesianism and even Fordism.[22]

Fascist corporatism

| Part of a series on |

| Fascism |

|---|

|

|

Organizations |

|

Lists |

|

Fascism's theory of economic corporatism involved management of sectors of the economy by government or privately controlled organizations (corporations). Each trade union or employer corporation would, theoretically, represent its professional concerns, especially by negotiation of labour contracts and the like. This method, it was theorized, could result in harmony amongst social classes.[32] Authors have noted, however, that de facto economic corporatism was also used to reduce opposition and reward political loyalty.[33]

In Italy from 1922 until 1943, corporatism became influential amongst Italian nationalists led by Benito Mussolini. The Charter of Carnaro gained much popularity as the prototype of a "corporative state", having displayed much within its tenets as a guild system combining the concepts of autonomy and authority in a special synthesis.[34] Alfredo Rocco spoke of a corporative state and declared corporatist ideology in detail. Rocco would later become a member of the Italian Fascist regime Fascismo.[35]

Italian Fascism involved a corporatist political system in which the economy was collectively managed by employers, workers and state officials by formal mechanisms at the national level.[36] This non-elected form of state officializing of every interest into the state was professed to reduce the marginalization of singular interests (as would allegedly happen by the unilateral end condition inherent in the democratic voting process). Corporatism would instead better recognize or "incorporate" every divergent interest into the state organically, according to its supporters, thus being the inspiration for their use of the term totalitarian, perceivable to them as not meaning a coercive system but described distinctly as without coercion in the 1932 Doctrine of Fascism as thus:

When brought within the orbit of the State, Fascism recognizes the real needs which gave rise to socialism and trade unionism, giving them due weight in the guild or corporative system in which divergent interests are coordinated and harmonized in the unity of the State.[37]

and

[The state] is not simply a mechanism which limits the sphere of the supposed liberties of the individual... Neither has the Fascist conception of authority anything in common with that of a police ridden State... Far from crushing the individual, the Fascist State multiplies his energies, just as in a regiment a soldier is not diminished but multiplied by the number of his fellow soldiers.[37]

A popular slogan of the Italian Fascists under Mussolini was, “Tutto nello Stato, niente al di fuori dello Stato, nulla contro lo Stato” (everything for the state, nothing outside the state, nothing against the state).

This prospect of Italian fascist corporatism claimed to be the direct heir of Georges Sorel's revolutionary syndicalism, such that each interest was to form as its own entity with separate organizing parameters according to their own standards, only however within the corporative model of Italian fascism each was supposed to be incorporated through the auspices and organizing ability of a statist construct. This was by their reasoning the only possible way to achieve such a function, i.e., when resolved in the capability of an indissoluble state. Much of the corporatist influence upon Italian Fascism was partly due to the Fascists' attempts to gain endorsement by the Roman Catholic Church that itself sponsored corporatism.[38]

However fascism's corporatism was a top-down model of state control over the economy while the Roman Catholic Church's corporatism favoured a bottom-up corporatism, whereby groups such as families and professional groups would voluntarily work together.[38][39] The fascist state corporatism influenced the governments and economies of a number of Roman Catholic-majority countries, such as the governments of Engelbert Dollfuss in Austria and António de Oliveira Salazar in Portugal, but also Konstantin Päts and Karlis Ulmanis in non-Catholic Estonia and Latvia. Fascists in non-Catholic countries also supported Italian Fascist corporatism, including Oswald Mosley of the British Union of Fascists who commended corporatism and said that "it means a nation organized as the human body, with each organ performing its individual function but working in harmony with the whole".[40] Mosley also considered corporatism as an attack on laissez-faire economics and "international finance".[40]

Salazar was not associated with Mussolini—quite the opposite; he banished the fascist party in Portugal and distanced himself from all of Europe's fascist regimes. Portugal during Salazar's reign was considered "Catholic Corporatism". Portugal remained neutral throughout World War II. Salazar also had a strong dislike of Marxism and Liberalism.

In 1933, Salazar stated, "Our Dictatorship clearly resembles a fascist dictatorship in the reinforcement of authority, in the war declared against certain principles of democracy, in its accentuated nationalist character, in its preoccupation of social order. However, it differs from it in its process of renovation. The fascist dictatorship tends towards a pagan Caesarism, towards a state that knows no limits of a legal or moral order, which marches towards it goal without meeting complications or obstacles. The Portuguese New State, on the contrary, cannot avoid, not think of avoiding, certain limits of a moral order which it may consider indispensable to maintain in its favour of its reforming action".[41]

Neo-corporatism

During the post-World War II reconstruction period in Europe, corporatism was favoured by Christian democrats (often under the influence of Catholic social teaching), national conservatives, and social democrats in opposition to liberal capitalism. This type of corporatism became unfashionable but revived again in the 1960s and 1970s as "neo-corporatism" in response to the new economic threat of recession-inflation.

Neo-corporatism favoured economic tripartism which involved strong labour unions, employers' unions, and governments that cooperated as "social partners" to negotiate and manage a national economy.[22] Social corporatist systems instituted in Europe after World War II include the ordoliberal system of the social market economy in Germany, the social partnership in Ireland, the polder model in the Netherlands, the concertation system in Italy, the Rhine model in Switzerland and the Benelux countries, and the Nordic model in Scandinavia.

Attempts in the United States to create neo-corporatist capital-labor arrangements were unsuccessfully advocated by Gary Hart and Michael Dukakis in the 1980s. Robert Reich as U.S. Secretary of Labor during the Clinton administration promoted neo-corporatist reforms.[42]

Chinese corporatism

Chinese corporatism, as described by Jonathan Unger and Anita Chan in their essay China, Corporatism, and the East Asian Model:[43]

"at the national level the state recognizes one and only one organization (say, a national labour union, a business association, a farmers' association) as the sole representative of the sectoral interests of the individuals, enterprises or institutions that comprise that organization's assigned constituency. The state determines which organizations will be recognized as legitimate and forms an unequal partnership of sorts with such organizations. The associations sometimes even get channelled into the policy-making processes and often help implement state policy on the government's behalf."

By establishing itself as the arbiter of legitimacy and assigning responsibility for a particular constituency with one sole organization, the state limits the number of players with which it must negotiate its policies and co-opts their leadership into policing their own members. This arrangement is not limited to economic organizations such as business groups and social organizations.

The use of corporatism as a framework to understand the central state's behaviour in China have been criticized by authors such as Bruce Gilley and William Hurst.[44][45]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Waite, Duncan. In press. “Imperial Hubris: The Dark Heart of Leadership.” Journal of School Leadership; Waite, Duncan, Turan, Selhattin & Niño, Juan Manuel. (2013). “Schools for Capitalism, Corporativism, and Corruption: Examples from Turkey and the US.” In Ira Bogotch & Carolyn Shields (eds.), International Handbook of Social (In)Justice and Educational Leadership (pp. 619-642). Dordercht, The Netherlands: Springer; Waite, Duncan & Waite, Susan F. (2010). “Corporatism and its Corruption of Democracy and Education.” Journal of Education and Humanities, 1(2), 86-106

- ↑ . Wiarda, Howard J (1996). Corporatism and Comparative Politics: The Other Great Ism. 0765633671: M.E. Sharpe. pp. 22–23. ISBN 0765633671.

- ↑ Wiarda, Howard J., pp. 27.

- ↑ Clarke, Paul A. B; Foweraker, Joe. Encyclopedia of democratic thought. London, UK; New York, USA: Routledge, 2001. Pp. 113

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wiarda, Howard J., pp. 35.

- 1 2 Adler, Franklin Hugh.Italian Industrialists from Liberalism to Fascism: The Political Development of the Industrial Bourgeoisie, 1906–34. Pp. 349

- 1 2 Wiarda, Howard J., pp. 10.

- 1 2 3 Murchison, Carl Allanmore; Allee, Warder Clyde. A handbook of social psychology, Volume 1. 1967. Pp. 150.

- ↑ Conwy Lloyd Morgan, Conwy Lloyd. Animal Behaviour. Bibliolife, LLC, 2009. Pp. 14.

- ↑ Wiarda, Howard J., pp. 31-38, 44, 111, 124, 140.

- ↑ Hans Slomp. European politics into the twenty-first century: integration and division. Westport, Connecticut, USA: Praeger Publishers, 2000. Pp. 81

- ↑ Social Democratic Corporatism and Economic Growth, by Hicks, Alexander. 1988. The Journal of Politics, vol. 50, no. 3, pp. 677-704. 1988.

- ↑ Bao-Er. China's Neo-traditional Rights of the Child. Blaxland, Australia: Lulu.com, 2006. Pp. 19.

- ↑ Wiarda, Howard J., pp. 28.

- 1 2 Wiarda, Howard J., pp. 31.

- ↑ Wiarda, Howard J., pp. 37.

- ↑ Wiarda, Howard J., pp. 38.

- ↑ Wiarda, Howard J., pp. 39.

- ↑ Wiarda, Howard J., pp. 41.

- 1 2 Wiarda, Howard J., pp. 29.

- 1 2 Wiarda, Howard J., pp. 33.

- 1 2 3 R. J. Barry Jones. Routledge Encyclopedia of International Political Economy: Entries A-F. Taylor & Frances, 2001. Pp. 243.

- ↑ Peter F. Klarén, Thomas J. Bossert. Promise of development: theories of change in Latin America. Boulder, Colorado, USA: Westview Press, 1986. Pp. 221.

- ↑ Francis Ludwig Carsten, Hermann Graml. The German resistance to Hitler. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, USA: University of California Press. Pp. 93

- ↑ Ferdinand Tönnies, José Harris. Community and civil society. Cambride University Press, 2001 (first edition in 1887 as Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft). Pp. xxxii-xxxiii.

- 1 2 3 Antony Black, pp. 226.

- ↑ Antony Black, pp. 223.

- ↑ Antony Black, pp. 226, 228.

- ↑ Gregg, Samuel. The commercial society: foundations and challenges in a global age. Lanham,USA; Plymouth, UK: Lexington Books, 2007. Pp. 109

- 1 2 Waring, Stephen P. Taylorism Transformed: Scientific Management Theory Since 1945. University of North Carolina Press, 1994. Pp. 193.

- ↑ Wiarda, Howard J., pp. 134.

- ↑ Mark Mazower, Dark Continent: Europe's 20th Century p29 ISBN 0-679-43809-2

- ↑ "Fascism." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, 2010. Web. 15 April 2010 <http://search.eb.com/eb/article-219369>.

- ↑ Parlato, Giuseppe (2000). La sinistra fascista (in Italian). Bologna: Il Mulino. p. 88.

- ↑ Payne, Stanley G. 1996. A History of Fascism, 1914-1945. Routledge. Pp. 64 ISBN 1-85728-595-6.

- ↑ The Routledge Companion to Fascism and the Far Right (2002) by Peter Jonathan Davies and Derek Lynch, Routledge (UK), ISBN 0-415-21494-7 p.143.

- 1 2 Mussolini – The Doctrine of Fascism

- 1 2 Morgan, Philip. Fascism in Europe, 1919-1945. Routledge, 2003. P. 170.

- ↑ Lewis, Paul H. Authoritarian regimes in Latin America: dictators, despots, and tyrants. Lanham, Maryland, USA: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc, 2006. Pp. 131. "Fascism differed from Catholic corporatism by assigning the state the role of final arbiter, in the event that employer and labor syndicates failed to agree."

- 1 2 Robert Eccleshall, Vincent Geoghegan, Richard Jay, Michael Kenny, Iain Mackenzie, Rick Wilford. Political Ideologies: an introduction. 2nd ed. Routledge, 1994. P. 208.

- ↑ Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review Vol. 92, No. 368, Winter, 2003

- ↑ Waring, Stephen P. Taylorism Transformed: Scientific Management Theory Since 1945. University of North Carolina Press, 1994. Pp. 194.

- ↑ "China,Corporatism,and the East Asian Model". By Jonathan Unger and Anita Chan, 1994.

- ↑ Bruce Gilley (2011) "Paradigms of Chinese Politics: Kicking Society Back Out", Journal of Contemporary China 20(70).

- ↑ William Hurst (2007) "The City as the Focus: The Analysis of Contemporary Chinese Urban Politics’, China Information 20(30).

References

- Black, Antony (1984). Guilds and civil society in European political thought from the twelfth century to present. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-416-73360-0.

- Wiarda, Howard J. (1997) Corporatism and comparative politics. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 978-1-56324-716-3.

Further reading

- Acocella, N. and Di Bartolomeo, G. [2007], ‘Is corporatism feasible?’, in: ‘Metroeconomica’, 58(2): 340-59.

- Jones, R. J. Barry. Routledge Encyclopedia of International Political Economy: Entries A-F. Taylor & Frances, 2001. ISBN 978-0-415-14532-9.

- Taha Parla and Andrew Davison, Corporatist Ideology in Kemalist Turkey Progress or Order?, 2004, Syracuse University Press, ISBN 0-8156-3054-9

On Italian corporatism

- Constitution of Fiume

- Rerum novarum: encyclical of Pope Leo XIII on capital and labor

- Quadragesimo Anno: encyclical of Pope Pius XI on reconstruction of the social order

On fascist corporatism

- Baker, David, The political economy of fascism: Myth or reality, or myth and reality?, '"New Political Economy'", Volume 11, Issue 2 June 2006, pages 227–250.

- Marra, Realino, Aspetti dell'esperienza corporativa nel periodo fascista, "Annali della Facoltà di Giurisprudenza di Genova", XXIV-1.2, 1991–92, pages 366–79.

- There is an essay on "The Doctrine of Fascism" credited to Benito Mussolini that appeared in the 1932 edition of the Enciclopedia Italiana, and excerpts can be read at Doctrine of Fascism. There are also links there to the complete text.

- My rise and fall, Volumes 1–2 – two autobiographies of Mussolini, editors Richard Washburn Child, Max Ascoli, Richard Lamb, Da Capo Press, 1998

- The 1928 autobiography of Benito Mussolini. Online. My Autobiography. Book by Benito Mussolini; Charles Scribner's Sons, 1928. ISBN 978-0-486-44777-3. ASIN: B0017RTP5G.

On neo-corporatism

- Katzenstein, Peter. Small States in World Markets: industrial policy in Europe. Ithaca, 1985. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-9326-3.

- Olson, Mancur. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. 1965, 1971. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-53751-4.

- Schmitter, P. C. and Lehmbruch, G. (eds.). Trends toward Corporatist Intermediation. London, 1979. ISBN 978-0-8039-9837-7.

- Rodrigues, Lucia Lima. "Corporatism, liberalism and the accounting profession in Portugal since 1755." Journal of Accounting Historians, June 2003.

External links

| Look up corporatism in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Encyclopedias

- Corporatism - Encyclopædia Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- Corporatism - The Canadian Encyclopedia

- Articles

- Professor Thayer Watkins, The economic system of corporatism, San Jose State University, Department of Economics

- Chip Berlet, "Mussolini on the Corporate State", 2005, Political Research Associates;

- "Economic Fascism" by Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Freeman, Vol. 44, No. 6, June 1994, Foundation for Economic Education; Irvington-on-Hudson, New York, USA.