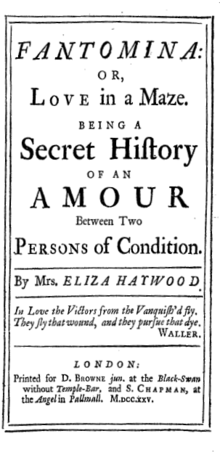

Fantomina

Fantomina; or Love in a Maze is a novel by Eliza Haywood published in 1725.[1] In it, the protagonist disguises herself as four different women in her efforts to seduce the man she loves. Part of the tradition of amatory fiction, it rewrites the story of the persecuted maiden, giving its heroine power and sexual desire.

Plot summary

The story opens in a London playhouse where the unnamed main character, intrigued by the men at the theater, decides to pretend she is a prostitute. She enjoys talking with one Beauplaisir and he, believing her favors to be for sale, asks to meet her. She demurs and puts him off until the next evening. In preparation, she rents lodgings and then meets him at the theater the following night. They go to the house and she realizes that Beauplaisir wants to have sex and resists him, but he does not listen to her protests and rapes her. Afterwards, she is despondent and rejects his money, which confuses Beauplaisir, who did not believe her protestations. Worried about her reputation, she gives her name as "Fantomina". Soon, however, Beauplaisir tires of her and leaves for Bath. She follows him. Dressed as a country girl, she obtains employment at the inn where he is staying, as a maid. When Beauplaisir sees her, he believes her to be a new maid, Celia, and, overcome by his desire, ravishes her. He gives her some money in recompense. He leaves Bath after about a month, tired of Celia. On his way home, he encounters Mrs. Bloomer and invites her into his carriage, who is the protagonist dressed as a widow. Her grief prompts him to try to raise her spirits, which results in them having sex in an inn along the way. Back in London, the heroine sends Beauplaisir a letter, signed "Incognita", declaring her undying love and passion for him. She writes there is nothing she will refuse him, except the sight of her face. They meet and she, wearing a mask, agrees to sleep with him in the dark. Beauplaisir keeps up each of these affairs, never realizing they are the same woman, but they both eventually tire of each other. She becomes pregnant and after she gives birth her mother insists she name the father. When Beauplaisir arrives, he does not know who she is until she tells her story. At the end, her mother sends her to live in a monastery in France.

Genre and style

Haywood's story "radically rewrites" the typical "persecuted maiden" story of the early eighteenth century.[2] The heroine is introduced as "A young lady of distinguished Birth, Beauty, Wit, and Spirit" visiting London from the country, who is "young, a Stranger to the World, and consequently to the Dangers of it; and having no Body in Town, at that Time, to whom she was oblig’d to be accountable for her Actions, did in every Thing as her Inclinations or Humour render’d most agreeable to her".[3] The reader thus expects the heroine to be seduced and reach a tragic end; such stories often taught readers about the dangers of "vulnerability, willfulness, and lack of guidance".[4] In Fantomina, however, the heroine does not die nor is she disgraced (the typical endings). Instead, Haywood uses the disguise, wit, and sexual freedom common to Restoration comedies to show the similarities between the two genres, one tragic and the other comic.[5] While Fantomina falls for Beauplaisir, like other maidens,[6] she is also a heroine with an explicit sexual desire. As critic Margaret Croskery writes, Haywood "refuses to define female sexual virtue in terms of chastity or a victimized sexual objecthood…. Instead, she defines virtuous love in terms of sincerity and constancy".[7]

Fantomina's ending, neither true to the "persecuted maiden" genre nor true to the marriages of Restoration comedies, is ambiguous. This would have shocked its readers. As one editor of the text writes, "where the traditional moral might be expected, this story ends with a casual delight in 'an Intreague, which, considering the Time it lasted, was as full of Variety as any, perhaps, that many Ages has produced'".[8]

Fantomina also descends from the political pornography of the seventeenth century, which unflatteringly portrayed London commoners as the source of democratic unrest and protest.[9] In the 1720s, Robert Walpole was attempting to limit the franchise in London. However, the political pornography of this time reversed the typical structure of these stories by portraying him as the villainous seducer and London as the "violated maiden".[10] Like these stories, Fantomina's heroine "ultimately triumph[s] over those who would self-servingly exploit the favors of London's commons”.[11]

Publication and reception

Fantomina was first published in 1725 in the second edition of Haywood’s collected works, which was entitled Secret Histories, Novels, and Poems.[12] Although Haywood was a popular writer at the time, few of her works were republished between the eighteenth century and 1963.[13] The reasons for this have to do with gender, "the bias against didactic and popular literature,...Haywood’s complicated experiments with genre", and the way that the history of the novel has been told in literary studies.[14] However, since the rise of feminist literary criticism, Haywood's works and those of other early eighteenth-century female novelists have received attention from scholars and Fantomina has now appeared in several anthologies beginning in the 1980s.[15]

Notes

- ↑ Fantomina is referred to variously as a "novel", "novella", and a "piece of short fiction" by scholars.

- ↑ Croskery, 72.

- ↑ Croskery, 72.

- ↑ Croskery and Patchias, 23

- ↑ Croskery and Patchias, 24.

- ↑ Ballaster, 189.

- ↑ Croskery, 78.

- ↑ Croskery and Patchias, 24.

- ↑ Mowry, 652.

- ↑ Mowry, 653.

- ↑ Mowry, 653.

- ↑ Croskery and Patchias, 11.

- ↑ Croskery and Patchias, 9.

- ↑ Croskery and Patchias, 9.

- ↑ Croskery and Patchias, 20.

Bibliography

- Ballaster, Ros. Seductive Forms: Women’s Amatory Fiction from 1684 to 1740. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992. ISBN 0-19-811244-0.

- Croskery, Margaret Case. "Masquerading Desire: The Politics of Passion in Eliza Haywood’s Fantomina." The Passionate Fictions of Eliza Haywood: Essays on Her Life and Work. Eds. Kirsten T. Saxton and Rebecca P. Bocchicchio. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2000. ISBN 0-8131-2161-2.

- Croskery, Margaret Case and Anna C. Patchias. "Introduction." Fantomina and Other Works. Peterborough: Broadview Press, 2004. ISBN 1-55111-524-7.

- Merritt, Juliette. "Peepers, Picts, and Female Masquerade: Performances of the Female Gaze in Fantomina; or, Love in a Maze." Beyond Spectacle: Eliza Haywood’s Female Spectators. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8020-3540-X.

- Mowry, Melissa. "Eliza Haywood's Defense of London's Body Politic". Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900 43.3 (Summer 2003): 645–665.

External links

- Fantomina, edited by Jack Lynch at Rutgers University