The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction

|

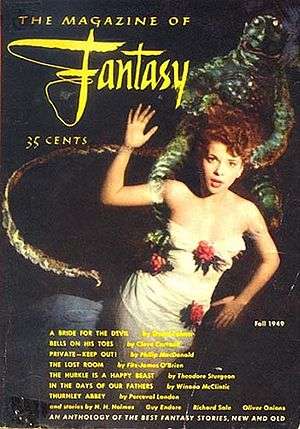

The first issue (Fall 1949) had a cover illustration by Bill Stone and displayed George Salter's calligraphic logo. Salter (1897-1967) had been the art director for Mercury Publications since 1939. He was F&SF's art editor from 1949 until 1958. | |

| Categories | Science Fiction; Fantasy Fiction |

|---|---|

| Frequency | Bimonthly |

| Year founded | 1949 |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| ISSN | 1095-8258 |

| OCLC number | 18737979 |

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction (later Fantasy & Science Fiction and usually referred to as just F&SF) is a digest-size American fantasy and science fiction magazine first published in 1949 by Mystery House and then by Fantasy House. Both were subsidiaries of Lawrence Spivak's Mercury Publications, which took over as publisher in 1958. Spilogale, Inc. has published the magazine since 2001. Since the April/May 2009 issue, it is published bimonthly with 256 pages per issue.[1]

Titles

It began as The Magazine of Fantasy (Fall 1949), with Anthony Boucher and J. Francis McComas as editors. To encompass the full spectrum of speculative fiction, the title expanded into The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction with the second issue. The quarterly became a bimonthly with the fifth issue (December 1950). Switching to an ampersand, it became The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction with the sixth issue (February 1951), returning to The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction when it went monthly with issue 17 (October 1952). The ampersand reappeared in May 1979, and the title was finally shortened to just Fantasy & Science Fiction with the October 1987 issue. With the April/May 2009 issue, it changed from monthly back to bimonthly publication.[2]

1940s-1950s

In the mid-1940s, McComas was the co-editor, with Raymond J. Healy, of the pioneering anthology, Adventures in Time and Space (1946). The massive volume, a Modern Library Giant, introduced many readers to science fiction when it appeared on library shelves during the post-WWII years. Boucher was writing radio scripts in the late 1940s, but he left dramatic radio in 1948, as he explained to William F. Nolan, "mainly because I was putting in a lot of hours working with J. Francis McComas in creating what soon became The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. We got it off the ground in 1949 and saw it take hold solidly by 1950. This was a major creative challenge, and although I was involved in a lot of other projects, I stayed with F&SF into 1958."[3]

In actuality, four years passed as Boucher and McComas attempted to launch their magazine of fantasy and supernatural stories. They initially proposed to Fred Dannay the notion of a sister publication for Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine. Dannay recommended them to Spivak. In January 1946, Boucher and McComas went to New York and met with Spivak, who suggested they assemble the contents for a test issue. Returning to California, they submitted their outline on March 11, 1946, resulting in a letter of agreement that August.

In September 1947, Joseph Ferman, the general manager of Mercury Publications, requested the complete material for the experimental issue to be titled Fantasy and Horror (subtitled A Magazine of Weird and Fantastic Stories). Boucher and McComas delivered this the following month. Studying sales figures of other digest-size magazines, Ferman postponed publication. A full year passed before he reactivated the project in February 1949, suggesting the addition of a science fiction story. Three months later, Ferman came up with the new title, The Magazine of Fantasy. On October 6, 1949, the magazine was introduced with a big splash during an invitational luncheon at the Waldorf-Astoria with Basil Rathbone as the master of ceremonies.

What Boucher and McComas were striving to reach was a literary plateau far above the pulp plotlines and action-adventures many associated with the genre, and one way they achieved this was with a concentration on reprints. By eliminating interior illustrations and displaying text in a single column across the page, they gave their magazine the appearance of a literary journal. The story prefaces Boucher wrote were carefully calculated to pull the reader into the first paragraphs of the stories, setting the tone while providing background information and insights. This was one of the magazine's more distinctive features, and some readers chose to go through and absorb all of Boucher's prefaces before deciding which story to read first. Nolan, in the dedication to his book, 3 to the Highest Power (1968), took note of Boucher's brilliance in those illuminating introductions:

For Anthony Boucher, who... in eighty-seven splendidly edited issues of Fantasy & Science Fiction, perfected the Grand Art of the Preface.

At the time of the magazine's debut, Spivak was well known as the moderator-producer of radio's American Mercury Presents: Meet the Press, in addition to publishing the unprofitable American Mercury magazine, 30 annual mystery reprints and the profitable Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, which had a 200,000 circulation. The Magazine of Fantasy was launched with a print run of 70,000. Interviewed by Time about Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine's new companion, Boucher looked ahead to monthly publication and commented, "The detective story is getting into a blind alley of repetition. Science fiction may be the next big escape."

Boucher's Berkeley residence at 2643 Dana Street served as F&SF's office, and shortly after the magazine began, the Berkeley Post Office called to inform Boucher that it was creating a special mail sack for all the incoming correspondence, a constant flow that included some 80 to 120 manuscript submissions each week.

The Magazine of Fantasy was subtitled An Anthology of the Best Fantasy Stories, Old and New. That first issue offered a mix of new contributions and reprints. The new stories were by Cleve Cartmill, H.H. Holmes (pseudonym for Anthony Boucher), Philip MacDonald, Winona McClintic and Theodore Sturgeon. The Sturgeon story, "The Hurkle Is a Happy Beast," later resurfaced in many anthologies. The reprints were Guy Endore's "Men of Iron" (1940), Richard Sale's "Perseus Had a Helmet" (1938), Stuart Palmer's "A Bride for the Devil" (1940), Perceval Landon's 1908 "Thurnley Abbey,"[4] Oliver Onions' 1910 "Rooum"[5] and Fitz-James O'Brien's "The Lost Room" (1858).[6]

The second issue, as The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, featured stories by W. L. Alden, Robert Arthur, Ray Bradbury, Robert M. Coates, Miriam Allen DeFord, Anthony Hope, Damon Knight, Kris Neville, Walt Sheldon and Margaret St. Clair, plus a collaboration of L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt. With "The Gnurrs Come from the Voodvork Out," that issue introduced Reginald Bretnor, who became the magazine's resident humorist for many issues to come, contributing such stories as "Bug-Getter."[7]

The third issue introduced the 23-year-old Richard Matheson, who made an indelible impression on readers with "Born of Man and Woman," his first published story.

Boucher and McComas began their "Recommended Reading" column in the second issue, with both editors handling the reviews. After the August, 1954 announcement that McComas was leaving the magazine to travel and write, Boucher took over as the sole book reviewer until his own departure in 1958.

When it began in 1949, the magazine was initially quarterly until the Fall 1950 issue. Frequency of publication increased to bimonthly in December 1950 and to monthly in 1952.

1990s-2000s

From 1991 to 2008 there were 11 issues per year (including an extended "anniversary double issue" every October). In January 2009, publisher-editor Gordon Van Gelder announced that as of April the magazine would reduce postage costs by switching to bimonthly publication of double issues, with a 10% net loss in content.[8] "In the end, we make about the same money from an electronic subscription as from a print sub," wrote Van Gelder on March 7, 2009.[9]

In January of 2015, Charles Coleman Finlay was named the 9th editor of the magazine.[10]

Circulation

Monthly circulation in 2011 was 14,462.[11] 2011 reported demographics of readership: 61% male, 39% female, 52% age 26-45, 23% 46-55, 93% have attended college, 28% have post-graduate degrees.[12]

Chronology of editors

- J. Francis McComas, Fall 1949 – August 1954

- Anthony Boucher, Fall 1949 – August 1958

- Cyril M. Kornbluth, 1958[13]

- William Tenn, 1958[14]

- Robert P. Mills, September 1958 – March 1962

- Avram Davidson, April 1962 – November 1964

- Joseph W. Ferman, December 1964 – December 1965 (supervising his son, Edward Ferman, who was the actual editor)

- Edward L. Ferman, January 1966 – June 1991

- Kristine Kathryn Rusch, July 1991 – May 1997

- Gordon Van Gelder, June 1997 – January 2015

- Charles Coleman Finlay, March 2015 – present

Columns and features

Robert Bloch wrote a notable series of essays on fandom in the 1950s. Following McComas and Boucher were other book critics, including Alfred Bester, Damon Knight, Avram Davidson, Judith Merril, James Blish, Joanna Russ, Algis Budrys, John Clute, Orson Scott Card, Charles de Lint, Elizabeth Hand and Michelle West. Charles Beaumont, Baird Searles, Harlan Ellison, Kathi Maio and Lucius Shepard have covered film and related media with, briefly, William Morrison reviewing live theater.

Isaac Asimov wrote a science column for the magazine that ran for 399 monthly issues without a break, from November 1958 to February 1992,[15] ending two months before his death, at which time he was in such poor health that he dictated the final essay to his wife Janet Asimov.[16] Theodore L. Thomas, Gregory Benford and Pat Murphy have also contributed science columns. Charles Platt contributed interviews and essays on speculative fiction. Various writers have highlighted literary oddities in the "Curiosities" column. The regular feature of humorous reader "Competitions" were collected by Ed Ferman in the anthology Oi, Robot. A series of shaggy dog stories known as "feghoots", written by Reginald Bretnor under his anagrammatic pseudonym Grendel Briarton, ran in the magazine from 1956 to 1973 with the series title "Through Space and Time with Ferdinand Feghoot".

Cover illustrators

In 1950-51 the magazine's art director George Salter painted almost all the front covers using an imaginative, surrealistic approach. Two exceptions were astronomical paintings by Chesley Bonestell for the December 1950 and August 1951 issues. Salter and Bonestell were joined in 1952 by Ed Emshwiller, who became, through three decades, the magazine's most prolific cover artist.

With a painting by George Gibbons on the August 1952 issue, F&SF introduced a wraparound cover, used by Hannes Bok for his illustration of Roger Zelazny's "A Rose for Ecclesiastes" (November 1963). World War II military and maritime artist Jack Coggins, who illustrated four F&SF covers in 1953-54, also did cover paintings for Galaxy Science Fiction and Thrilling Wonder Stories during this same period.

F&SF's top ten cover illustrators ranked by number of paintings (up to April 2005) were: Ed Emshwiller (70), Ron Walotsky (60), David A. Hardy (56), Chesley Bonestell (42), Mel Hunter (32), Barclay Shaw (24), Jill Bauman (23), Jack Gaughan (21), Kent Bash (17) and Bryn Barnard (14).

Unlike F&SF's companion magazine, Venture Science Fiction Magazine, The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction did not use interior illustrations of stories, except for 14 issues (April–October 1954, September–December 1956, September 1957 and April–May 1959). These interior illustrations were by Emshwiller, Kelly Freas and others.

However, it did occasionally use cartoons as fillers on the last page of a story. Gahan Wilson contributed a cartoon to every issue for more than 15 years. Sidney Harris was also a frequent cartoon contributor, prompting Budrys's comment, "Harris is different. Harris plays with science and technology... and he's funny."[17]

Fantasy Records, began in 1949, and the jazz recording company's first subsidiary label, formed in 1951, was Galaxy Records. The two labels were named in honor of F&SF and Galaxy Science Fiction. The Eureka Years, a history and anthology of fiction and correspondence from the first years of F&SF, makes the claim that George Salter's first logo for the magazine was imitated by the Circle Record Company for the logo of their Fantasy Records. However, the early Fantasy Records' logo actually bears little resemblance to Salter's calligraphy.

Notable authors and stories

- Thomas M. Disch's On Wings of Song was the first fantasy or sf magazine serial to be nominated for the American Book Award. Disch's "The Brave Little Toaster" became a Hyperion Pictures animated film in 1987.

- "Jeffty is Five" and "The Deathbird" by Harlan Ellison. He also contributed both a regular film column and many of his best stories to the magazine.[18]

- Howard Fast's "The Martian Shop"[19]

- Robert A. Heinlein's Starship Troopers, October, November 1959, serialized as "Starship Soldier".

- Shirley Jackson's "One Ordinary Day, with Peanuts".

- Daniel Keyes's Flowers for Algernon. A Hugo Award-winning novelet which led to many radio, TV, stage and films, notably Charly (1968).

- Stephen King's The Dark Tower short stories which comprised the first volume, beginning with "The Gunslinger" (October, 1978).

- Fritz Leiber's "Ill Met in Lankhmar" won the 1970 Nebula Award for Best Novella and the 1971 Hugo Award for Best Novella (1970).

- A Canticle for Leibowitz by Walter M. Miller, Jr.. The novelets were incorporated into the novel and later adapted into NPR radio dramas.

- Kurt Vonnegut's "Harrison Bergeron"

Special author issues

F&SF assembled more than a dozen special issues devoted to a single author, beginning with a special issue on Theodore Sturgeon (September 1962), followed by Ray Bradbury (May 1963), Isaac Asimov (October 1966), Fritz Leiber (July 1969), Poul Anderson (April 1971), James Blish (April 1972), Frederik Pohl (September 1973), Robert Silverberg (April 1974), Damon Knight (November 1976), Harlan Ellison (July 1977), Stephen King (December 1990), Lucius Shepard (March 2001), Kate Wilhelm (September 2001), Barry N. Malzberg (June 2003) and Gene Wolfe (April 2007).

Anthologies

In 1952, Boucher and McComas began their annual hardcover anthology series, The Best from Fantasy and Science Fiction. Initially published by Little Brown, the series moved to Doubleday in 1954. Ace published later paperback editions. After the first three in the series, McComas dropped out, leaving Boucher as the sole editor.[20] Eventually, the series was not published annually but instead appeared irregularly. More recently, the books have been theme anthologies, edited by Gordon Van Gelder. Earlier, Ed Ferman co-edited The Best Horror Stories from Fantasy and Science Fiction with Anne Devereaux Jordan during his tenure as editor. In 2009, Van Gelder compiled The Very Best of Fantasy & Science Fiction: Sixtieth Anniversary Anthology, including stories in F&SF issues ranging from 1951 (Alfred Bester's "Of Time and Third Avenue") to 2007 ("The Merchant and the Alchemist's Gate" by Ted Chiang).[21]

Current staff

- Gordon Van Gelder, editor, June 1997 – January 2015; publisher, 2001 – present

- Charles Coleman Finlay, editor, January 2015 – present

- Barbara J. Norton, assistant publisher, 2001 – present

- Keith Kahla, assistant publisher, 2001 – present

- Robin O'Connor, assistant editor, 1990 – present

- Stephen Mazur, assistant editor, 2010 – present

- Scott Polhemus, editorial assistant, 2012 – present

- Anna Will, editorial assistant, June 2015 – present

- Harlan Ellison, film editor, 1990 – present

- Carol Pinchefsky, contests editor, 2004 – present

- Rebecca French, subscriptions and marketing, 2010 – present

Sources

- Bradbury Chronicles Correspondence Database

- Indiana University: Lilly Library Manuscript Collections: Anthony Boucher/William Anthony Parker White Mss. (30,000 items spanning 1932-69)

- Locus: The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction Checklist

See also

References

- ↑ F&SF Goes Bimonthly

- ↑ F&SF is going bimonthly

- ↑ Nolan, William F. MysteryNet: "Who Was Anthony Boucher?"

- ↑ Landon, Perceval. "Thurnley Abbey" (1908) (full text)

- ↑ Onions, Oliver. "Rooum" (1910) (full text)

- ↑ O'Brien, Fitz-James. "The Lost Room" (1858) (full text)

- ↑ Bretnor, Reginald. "Bug-Getter," The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (January 1960) (full text)

- ↑ F&SF is going bimonthly

- ↑ Distribution problems

- ↑ Finlay Named Editor of F&SF, retrieved 16 January 2015

- ↑ 2011 Magazine Summary, Locus, February 2012, pages 56-7.

- ↑ http://www.sfsite.com/fsf/adinfo.htm

- ↑ NNDB Biography, accessed March 30, 2009.

- ↑ "...and a kind of excuse-it-please memoir," by William Tenn, Fantasy and Science Fiction, March 2009, pp.63-69.

- ↑ "Essays by Isaac Asimov from The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction" by Edward Seiler and Richard Hatcher on asimovonline.com

- ↑ "I. Asimov; A Memoir", 'Epilogue by Janet Asimov'

- ↑ Science Cartoons

- ↑ http://www.sfcovers.net/Magazines/FSF/FSF_0314.jpg

- ↑ Fast, Howard. The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, "The Martian Shop" (November 1959) (full text).

- ↑ The Best of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Sixth Series. Doubleday, 1957. (full text)

- ↑ San Francisco: Tachyon Publications (ISBN 978-1-892391-91-9).

External links

- Fantasy & Science Fiction Official website

- Fantasy & Science Fiction Czech edition

- Jack Coggins Gallery of Illustrations

- S. Harris Cartoon Gallery

- Visual Index of Science Fiction Cover Art (VISCO), includes F&SF cover archive (1949 – current)

- "Wonder World"; Time, October 10, 1949 (announcement of Magazine of Fantasy, its first issue published the previous week)

- Suvudu (Random House, Inc.) and The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction Join Forces

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||