Population control in Singapore

Population control in Singapore spans two distinct phases: first to slow and reverse the boom in births that started after World War II; and then, from the 1980s onwards, to encourage parents to have more children because birth numbers had fallen below replacement levels. Government eugenics policies flavoured both phases. In 1960s and 1970s, the anti-natalist policies flourished. The Family Planning and Population Board (FPPB) was established, initially advocating small families but eventually running the Stop at Two programme, which pushed for small two-children families and promoted sterilisation. From 1969 it was also used by government leaders to target lowly educated and low-income women in an experiment with eugenics policies to solve social concerns.

Government leaders also announced the Graduate Mothers' Scheme in 1984, which favoured the children of mothers with a university degree in primary school placement and registration process over the lesser-educated.[1][2] After the outcry in the 1984 general elections it was eventually scrapped.[3][4]

Singapore had also been undergoing the demographic transition and birth rates had fallen precipitously. The government eventually became pro-natalist, and officially announced its replacement Have Three or More (if you can afford it) in 1987, in which the government continued its efforts to better the quality and quantity of the population while discouraging low-income families from having children. The Social Development Unit (SDU) was also established in 1984 to promote marriage and romance between educated individuals.

Different sources have offered differing judgments on the government policies' impact on the population structure of Singapore. While Stop at Two has been described as basically successful or "over-successful", sceptics of interventionism claim that the demographic transition would have occurred anyway – noting that the government's attempts at reversing the falling birth rates due to the demographic transition have been less than successful.[5][6][7][8]

Post war trends and family planning

From 1947 to 1957, the social forces which caused the post–World War II baby boom elsewhere in the world also occurred in Singapore.[9] The birth rate rose and the death rate fell; the average annual growth rate was 4.4%, of which 1% was due to immigration; Singapore experienced its highest birth rate in 1957 at 42.7 per thousand individuals. (This was also the same year the United States saw its peak birth rate.)

Family planning was introduced to Singapore in 1949 by a group of volunteers that eventually became the Family Planning Association of Singapore and established numerous sexual health clinics offering contraception, treatments for minor gynaecological ailments, and marital advice. Until the 1960s there was no official government policy in these matters, but the postwar British colonial administration, followed by the Singaporean government, played an increasingly important role by providing ever larger grants to the Association, as well as land for its facilities network, culminating in 1960 with a three-month nationwide family planning campaign that was jointly conducted by the Association and government. The population growth rate slowed from 4–5% per year in the 1950s to around 2.5% in 1965 around independence. The birth rate had fallen to 29.5 per thousand individuals, and the natural growth rate had fallen to 2.5%.[7]

Singapore's population expansion can be seen in the graph below:

| Period | Growth |

|---|---|

| 1947–1957 | 84.7% |

| 1957–1970 | 90.8% |

| 1970–1980 | 13.3% |

| 1980–1990 | 18.5% |

| 1990–2000 | 20.6% |

| 2000–2010 | 40.9% |

Overcrowding concerns

At the time of independence, many Singaporeans lived in the Central Area in overcrowded shophouses; and the bulk of the work of the Housing Development Board had not yet been completed. In 1947, the British Housing Committee Report noted Singapore had "one of the world's worst slums – 'a disgrace to a civilised community'", and the average person per building density was 18.2 by 1947 (high-rise buildings had yet to be constructed en masse); about 550,000 people lived in squalid squatter settlements or "ramshackle shophouses" by 1966.[10] Rapid population growth was perceived as a threat to "political stability and living standards" that led to population overcrowding that would overwhelm employment opportunities and social services in education, health and sanitation.[5]

Despite their fall since 1957, birth rates in the 1960s were still perceived as high. On average, a baby was born every 11 minutes in 1965; Kandang Kerbau Hospital (KKH) – a women's hospital where most babies in Singapore were delivered – saw over 100 deliveries per day in 1962. In 1966, KKH delivered 39,835 babies, earning it a place in the Guinness Book of World Records for "largest number of births in a single maternity facility" each year for ten years. Because there was generally a massive shortage of beds in that era, mothers with routine deliveries were discharged from hospitals within 24 hours.[11]

Establishment of the FPPB

In 1959, the People's Action Party came to power, and in September 1965 the Minister for Health, Yong Nyuk Lin, submitted a white paper to Parliament, recommending a Five-year Mass Family Planning programme that would reduce the birth rate to 20.0 per thousand individuals by 1970. This was to become the National Family Programme; in 1966, the Family Planning and Population Board (FPPB) had been established based on the findings of the white paper, providing clinical services and public education on family planning.[5] Initially allocated a budget of $1 million SGD for the entire programme, the FPPB faced a resistant population, but eventually serviced over 156,000. The Family Planning Association was absorbed into the activities of the FPPB.

Lee Kuan Yew as first Prime Minister of Singapore held wide sway over the government's social policies before 1990. Lee Kuan Yew was recorded in 1967 as believing that "five percent" of a society's population, "who are more than ordinarily endowed physically and mentally," should be allocated the best of a country's limited resources to provide "a catalyst" for that society's progress. Such a policy for Singapore would "ensure that Singapore shall maintain its pre-eminent place" in Southeast Asia. Similar views shaped education policy and meritocracy in Singapore.[12]

Stop at Two

In the late 1960s, Singapore was a developing nation and had not yet undergone the demographic transition; though birth rates fell from 1957 to 1970, in 1970, birth rates rose as women who were themselves the product of the postwar baby boom reached maturity. Fearing that Singapore's growing population might overburden the developing economy, Lee started a vigorous Stop at Two family planning campaign. Abortion and sterilisation were legalised in 1970, and women were urged to get sterilised after their second child. Women without an O-level degree, deemed low-income and lowly educated, were offered by the government seven days' paid sick leave and $10,000 SGD in cash incentives to voluntarily undergo the procedure.[5][9][13]

The government also added a gradually increasing array of disincentives penalising parents for having more than two children between 1969 and 1972, raising the per-child costs of each additional child:[5][14]

- Workers in the public sector would not receive maternity leave for their third child or any subsequent children

- Hospitals were required to charge incrementally higher fees for each additional child.

- Income tax deductions would only be given for the first two children

- Large families were penalised in housing assignments.

- Third or fourth children were given lower priorities in education;

- Top priority in top-tier primary schools would be given only to children whose parents had been sterilised before the age of forty.

The government created a large array of public education material for the Stop at Two campaign, in one of the early examples of the public social engineering campaigns the government would continue to implement (e.g. the Speak Mandarin, Speak Good English, National Courtesy, Keep Singapore Clean and Toilet Flushing Campaigns) that would lead to its reputation as "paternalistic" and "interventionist" in social affairs.[9][15] The "Stop at Two" media campaign from 1970 to 1976 was led by Basskaran Nair, press section head of the Ministry of Culture, and created posters with lasting legacy: a 2008 Straits Times article wrote, "many middle-aged Singaporeans will remember the poster of two cute girls sharing an umbrella and an apple: The umbrella fit two nicely. Three would have been a crowd."[8] This same poster was also referred to in Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong's 2008 National Day Rally speech. Many other posters from the "iconic" campaign included similar themes of being content with two girls, to combat the common trend in developing Asian societies for families with only daughters to continue "trying for a boy".

In addition to promoting just having two children, the government also encouraged individuals to delay having their second child and to marry late, reinforcing the inevitable demographic transition. Other slogans and campaign material exhorted Singaporeans with such messages as:

- "Small Families – Brighter Future: Two is enough" (this message captioned a photo two young girls)

- "The second can wait" (a mother and father are seen as being happy with one child)

- "Teenage marriage means rushing into problems: A happy marriage is worth waiting for"

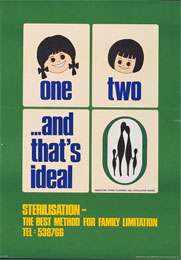

- "One, Two: And that's ideal: Sterilisation, the best method for Family Limitation" (shown with a cartoon of two girls' faces)

- "Take your time to say 'yes'"[11]

- Small Family: Brighter Future

- "Please stop at two!" (a stork carries a four-member nuclear family)[16]

The Straits Times interviewed mothers who were sterilised in that era, noting it was common to get sterilised at a young age, citing a woman who had undergone tubal ligation at KKH at the age of 23, herself coming from a large family of ten. "The pressure [disincentives] was high. The Government clearly didn't want us to have more than two." A gynaecologist doctor who worked KKH recalled sterilisation rates became "sky high" after the disincentives had been implemented; it was common for hospital workers to chide women who were pregnant with third-order or higher births, recommending abortions, while such women talked about their pregnancy "[as if] they committed a crime". The Straits Times also suggested the disincentives had been very effective; one woman cited how sterilisation certification had to be shown to a school for a third child to receive priority, while she and four out of five sisters eventually underwent sterilisation.[8] Expensive delivery fees ("accouchement fees") for third-order and higher births would also be waived with sterilisation.

The campaign was known to target the uneducated in particular; Lee believed that, "Free education and subsidised housing lead to a situation where the less economically productive people ... are reproducing themselves at [a higher rate]." He believed that implementing a system of government disincentives would stop "the irresponsible, the social delinquents" from thinking that having more children would entitle them to more government-provided social services.[17]

- We must encourage those who earn less than $200 per month and cannot afford to nurture and educate many children never to have more than two...we will regret the time lost if we do not now take the first tentative steps towards correcting a trend which can leave our society with a large number of the physically, intellectually and culturally anaemic. Lee Kuan Yew, 1969[17]

The government justified its social policy as a means of encouraging the poor to concentrate their limited resources on nurturing their existing children, making them more likely to be capable, productive citizens.[5] The government also had to respond to criticism that this policy favoured Chinese over minority races; Malays and Indians were stereotyped to have higher birth rates and bigger families than the Chinese, further fuelling accusations of eugenics.[18]

The demographic transition and the Graduate Mothers Scheme

As Singapore modernised in the 1970s, fertility continued to drop. The natural replacement rate reached 1.006 in 1975; thereafter the replacement rate would drop below unity. Furthermore, the so-called "demographic gift" was occurring in Singapore as with other countries; increases in income, education and health and the role of women in the workforce were strongly correlated to levels of low population growth. According to a paper by the Library of Congress, by the 1980s, "Singapore's vital statistics resembled those of other countries with comparable income levels but without Singapore's publicity campaigns and elaborate array of administrative incentives."[5]

Lee Kuan Yew was alarmed at the perceived demographic trend that educated women – most of all the college-educated – would be less likely to marry and procreate. Such a trend would run antithetical to his demographic policy, and part of this failure, Lee conjectured, was "the apparent preference of male university graduates for less highly educated wives". This trend was deemed in a 1983 speech as "a serious social problem".[5] Starting 1984, the government of Singapore gave education and housing priorities, tax rebates and other benefits to mothers with a university degree, as well as their children. The government also encouraged Singapore men to choose highly educated women as wives, establishing the Social Development Unit (SDU) that year to promote socialising among men and women graduates, a unit that was also nicknamed "Single, Desperate and Ugly".[5][18] The government also provided incentives for educated mothers to have three or four children, in what was the beginning of the reversal of the original Stop at Two policy. The measures sparked controversy and what became known as The Great Marriage Debate in the press. Some sections of the population, including graduate women, were upset by the views of Lee Kuan Yew, who had questioned that perhaps the campaign for women's rights had been too successful:

Equal employment opportunities, yes, but we shouldn't get our women into jobs where they cannot, at the same time, be mothers...our most valuable asset is in the ability of our people, yet we are frittering away this asset through the unintended consequences of changes in our education policy and equal career opportunities for women. This has affected their traditional role ... as mothers, the creators and protectors of the next generation.

In 1985, especially controversial portions of the policy that gave education and housing priorities to educated women were eventually abandoned or modified.[5][14]

A 1992 study noted that 61% of women giving birth had secondary education or higher, but this proportion dropped for third-order births (52%) and fourth-or-higher-order births (36%), supporting the idea that more children per capita continue to be born to women with less qualifications, and correspondingly, lower income.[13]

Have Three or More (if you can afford it)

In 1986 the government had recognised that falling birth rates were a serious problem and began to reverse its past policy of Stop at Two, encouraging higher birth rates instead. By 30 June of that year, the government had abolished the Family Planning and Population Board,[19] and by 1987, the total fertility rate had dropped to 1.44. That year, Goh Chok Tong announced a new slogan: Have Three or More (if you can afford it), announcing that the government now promoted a larger family size of three or more children for married couples who could afford them, and promoted "the joys of marriage and parenthood".[5] The new policy took into account Singapore's falling fertility rate and its increased proportion of the elderly, but was still concerned with the "disproportionate procreation" of the educated versus the uneducated, and discouraged having more than two children if the couple did not have sufficient income, to minimise the amount of welfare aid spent on such families.[13] The government also relaxed its immigration policies.

In October 1987, future Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, then a young Brigadier General, exhorted Singaporeans to procreate rather than "passively watch ourselves going extinct".[20] United Press International noted the "baffled" reaction of parents, many who had grown up in an era where they were told that having more than two children was "antisocial". One parent commented, "are we being told to have more children for the sake of the country or for ourselves?"[21] Goh Chok Tong, despite the scepticism, remained optimistic that the population rate would restored to the replacement rate by 1995. An NUS sociologist however, observed that Singapore had "a new breed of women" – one "involved in their careers [and] used to a certain amount of leisure and more material possessions" – and hence would not be as receptive to financial incentives like previous women of the 1960s and the 1970s. As of 2011, Singapore's birth rate has not yet been restored to replacement level.[22]

Policy comparisons between Have Three or More and Stop at Two, starting 1988

- Mothers with a third child would get 750 SGD in child relief (factoring historic exchange rates, this was about $662 in 2010 US dollars). If a mother had three 'O'-level passes in one sitting, she would qualify for an enhanced child relief rebate (lowered from a threshold of five passes). Having a fourth child would qualify for enhanced child relief of 750 SGD plus 15% of the mother's income, up to $10000 SGD.

- All disincentives and penalties given in school registration to families with more than two children are to be removed; in the presence of competition, priority would be allocated to families with more than two children.

- Subsidies for each child in a government-run or government-approved child care centre

- Medisave could now be authorised for hospital costs of a third child (previously forbidden under the Stop at Two policy)

- Families with more than two children with a HDB flat of three rooms or higher would receive priority if they desired to upgrade to a larger flat

- "Abortions of convenience" discouraged, with compulsory abortion counselling

- Women undergoing sterilisation with less than three children would receive compulsory counselling

- Expansion of the SDU's role and authority; recognising that the low birth rate reflected late marriages, the SDU also wooed those with postsecondary A-level qualifications rather than just college graduates

- Starting 1990, a tax rebate of 20,000 SGD (US$18,000 in 2010 dollars, factoring historic exchange rates) were given to mothers who had their second child before the age of 28

- Starting 1993, the sterilisation cash grant for lowly educated women was liberalised, allowing women to agree to use reversible contraception rather than sterilisation; educational bursaries for existing children were added as existing benefits, so long as the number did not exceed two.[13]

Modern legacy and current practices

The modern SDU, renamed the Social Development Network in 2009, encourages all Singaporean couples to procreate and marry to reverse Singapore's negative replacement rate. Some of the social welfare, dating and marriage encouragement, and family planning policies are also managed by the Ministry of Community Development, Youth and Sports.

Channel NewsAsia reported in January 2011 that the fertility rate of Singaporeans in 2010 were 1.02 for Chinese, 1.13 for Indians and 1.65 for Malays. In 2008, Lee Kuan Yew, known for his remarks on the Malay community, said the below-national-average birth rate for the Chinese was a "worrying trend".[23] That same year, he was quoted as saying, "[If] you marry a non-graduate, then you are going to worry if your son or daughter is going to make it to the university."[17][24]

Different sources have offered differing judgments on the government policies' impact on the population structure of Singapore. While most agree that the policies have been very interventionist, comprehensive and broad, the Library of Congress Country Study argues "it is impossible to separate the effects of government policies from the broader socioeconomic forces promoting later marriage and smaller families," suggesting that the government could only work with or work against much more powerful natural demographic trends. To the researchers of the study, the methods used in 1987 to attempt to reverse the falling birth rate was a demonstration of "the government's [continued] assumption" that citizens were receptive towards monetary incentives and administrative allocation of social services when it came to family planning.[5]

However Saw Swee Hock, a statistician and demographer quoted in the Straits Times in 2008, argued the demographic transition "was rapid because of the government's strong population control measures," but also admitted that, "even without the Stop at Two policy, the [total fertility rate] would have gone below 2.1 due to [the demographic transition]."[8] When demographic transition statistics are examined – in 1960, the total fertility rate was approximately ~6 – Asian MetaCentre researcher Theresa Wong notes that Singaporean birth rates and death rates fell dramatically in a period that occurred over "much shorter time period than in Western countries," yet such a short time frame is also seen in other Southeast Asian countries, where family planning campaigns were much less aggressive.[9] According to Saw Swee Hock, "the measures were comprehensive and strong, but they weren't reversed quickly enough".

Though newer modern policies exhibit "signs that the government is beginning to recognise the ineffectiveness of a purely monetary approach to increasing birth rates", a former civil servant noted that the government needs "to learn to fine-tune to the emotions rather than to dollars and cents. It should appeal more to the sense of fulfilment of having children". Such measures include promoting workplaces that encourage spending time with the family, and creating a "Romancing Singapore Campaign" that "[directly avoided being linked] to pro-children and pro-family initiatives," since "people get turned off" when the government appears to intervene in such intimate social affairs as marriage. However, this is still seen by some citizens as "trivialising" love and "emotional expression", which "should not be engineered".[8][9] In 2001, the government announced a Baby Bonus scheme, which paid $9000 SGD for the second child and $18000 for the third child over six years to "defray the costs of having children", and would match "dollar for dollar" what money parents would put into a Child Development Account (CDA) up to $6000 and $12000 for the second and third child respectively. In 2002, Goh Chok Tong advised "pragmatic" late marriers "to act fast. The timing is good now to get a choice flat to start a family."[25]

See also

References

- ↑ Pekka Louhiala (2004). Preventing intellectual disability: ethical and clinical issues. Cambridge University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-521-53371-3.

- ↑ Chadwick, Ruth (2000). Ethics, reproduction, and genetic control. Psychology Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-415-08979-1.

- ↑ Quah, Jon (1985). "Singapore in 1984: Leadership Transition in an Election Year". Asian Survey: 225. doi:10.1525/as.1985.25.2.01p0247v. JSTOR 2644306.

- ↑ Diane K. Mauzy; Robert Stephen Milne (2002). Singapore politics under the People's Action Party. Routledge. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-415-24653-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Singapore: Population Control Policies". Library of Congress Country Studies (1989). Library of Congress. Retrieved 11 August 2011.

- ↑ Fred Pearce (2010). The coming population crash: and our planet's surprising future. Beacon Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-8070-8583-7.

- 1 2 Mui, Teng Yap (2007). "Singapore: Population Policies

and Programs". In . Robinson, Warren C; Ross, John A. The global family planning revolution: three decades of population policies and programs. World Bank Publications. pp. 201–219. ISBN 978-0-8213-6951-7. line feed character in

|chapter=at position 31 (help) - 1 2 3 4 5 Toh, Mavis (24 August 2008). "ST: Two is not enough". The Straits Times. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Wong, Theresa; Brenda Yeoh (2003). "Fertility and the Family: An Overview of Pro-natalist Population Policies in Singapore" (PDF). ASIAN METACENTRE RESEARCH PAPER SERIES (12).

- ↑ Yuen, Belinda (November 2007). "Squatters no more: Singapore social housing". Global Urban Development Magazine 3 (1).

- 1 2 "Family Planning". National Archives. Government of Singapore. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- ↑ Diane K. Mauzy, Robert Stephen Milne, Singapore politics under the People's Action Party (Routledge, 2002).

- 1 2 3 4 Mui, Teng Yap (1995). "Singapore's 'Three or More' Policy: The First Five Years". Asia-Pacific Population Journal 10 (4): 39–52. Retrieved 11 August 2011.

- 1 2 Jacobson, Mark (January 2010). "The Singapore Solution". National Geographic Magazine. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

- ↑ "Poster Collection". Singapore Collection. Lee Kong Chian Reference Library. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- ↑ "National Family Planning Programme – Stop at Two". healthcare50.sg. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 Chee, Soon Juan (2008). A Nation Cheated. ISBN 981-08-0819-4.

- 1 2 Webb, Sara (26 April 2006). "Pushing for babies: S'pore fights fertility decline". Reuters. Retrieved 11 August 2011.

- ↑ "SINGAPORE FAMILY PLANNING AND POPULATION BOARD(REPEAL) ACT". Singapore Statutes. Parliament of Singapore. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- ↑ "Singapore – Government". Country Studies Program. Library of Congress. Retrieved 11 August 2011.

- ↑ Youngblood, Ruth (21 June 1987). " "'Stop at 2' Campaign Works Too Well; Singapore Urges New Baby Boom". United Press International. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ↑ "Department of Statistics, Singapore. Infographic on Crude Birth Rate" (PDF). www.singstat.gov.sg. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- ↑ De Souza, Ca-Mie (17 August 2008). "Chinese community assured, new initiatives for Malay/Muslims". Channel NewsAsia. Retrieved 11 August 2011.

- ↑ "Eugenics in Singapore". Your SDP. 9 November 2008. Retrieved 11 August 2011.

- ↑ "Opening of Parliament". Singapore Parliamentary Proceedings. Parliament of Singapore.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)