Aromatase excess syndrome

| Aromatase excess syndrome | |

|---|---|

AES results when the function of aromatase is hyperactive. The aromatase protein (pictured) is responsible for the biosynthesis of estrogens like estradiol in the human body. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

| OMIM | 139300 |

| MeSH | C537436 |

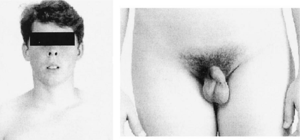

Aromatase excess syndrome (AES or AEXS), also sometimes referred to as familial hyperestrogenism or familial gynecomastia, is a rare genetic and endocrine syndrome which is characterized by an overexpression of aromatase, the enzyme responsible for the biosynthesis of the estrogen sex hormones from the androgens, in turn resulting in excessive levels of circulating estrogens and, accordingly, symptoms of hyperestrogenism. It affects both sexes, manifesting itself in males as marked or complete phenotypical feminization (with the exception of the genitalia; i.e., no pseudohermaphroditism), in whom it fits the definition of a form of intersex, and in females as hyperfeminization.[1][2][3]

To date, 10 families with AES have been fully described in the medical literature, of which 23 males and at least 6 females were characterized as displaying symptoms of the condition.[1][4]

Cause

The root cause of AES is not entirely clear, but it has been elucidated that inheritable, autosomal dominant genetic mutations affecting CYP19A1, the gene which encodes aromatase, are involved in its etiology.[1][3][4]

Observed physiological abnormalities of the condition include a dramatic overexpression of aromatase and, accordingly, excessive levels of estrogens including estradiol and estrone,[5] and a very high rate of peripheral conversion of androgens to estrogens. In one study, cellular aromatase mRNA expression was found to be at least 10 times higher in a female patient compared to the control, and the estradiol/testosterone ratio after an injection of testosterone in a male patient was found to be 100 times greater than the control.[1] Additionally, in another study, androstenedione, testosterone, and dihydrotestosterone (DHT) were found to be either low or normal in males, and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels were very low (likely due to suppression by estrogen, which has antigonadotropic effects as a form of negative feedback inhibition on sex steroid production in sufficiently high amounts),[6] whereas luteinizing hormone (LH) levels were normal.[4]

Symptoms

The symptoms of AES, in males, include heterosexual precocity (precocious puberty with phenotypically-inappropriate secondary sexual characteristics; i.e., a fully or mostly feminized appearance), severe prepubertal or peripubertal gynecomastia (development of breasts in males before or around puberty), hypogonadism (dysfunctional gonads), oligozoospermia (low sperm count), small testes, micropenis (an ususually small penis), advanced bone maturation, an earlier peak height velocity (an accelerated rate of growth in regards to height),[7] and short final stature due to early epiphyseal closure, and in females, isosexual precocity (precocious puberty with phenotypically-appropriate secondary sexual characteristics), macromastia (excessively large breasts), an enlarged uterus, menstrual irregularities, and, similarly to males, accelerated bone maturation and short final height. Fertility, though usually affected to one degree or another—especially in males—is not always impaired significantly enough to prevent sexual reproduction, as evidenced by vertical transmission of the condition by both sexes.[1][2][3]

Individuals with AES may be at higher risk of developing estrogen-sensitive cancers such as breast and endometrial cancer.[8][9] At least one patient, a male with the condition, was reported as having developed carcinoma of the breast.[1]

Treatment

Several treatments have been found to be effective in managing AES, including aromatase inhibitors and gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues in both sexes, androgen replacement therapy with non-aromatizable androgens such as DHT in males, and progestogens (which, by virtue of their antigonadotropic properties at high doses, suppress estrogen levels) in females. In addition, male patients often seek bilateral mastectomy, whereas females may opt for breast reduction if warranted.[1][2][3]

Medical treatment of AES is not absolutely necessary, but it is recommended as the condition, if left untreated, can lead to excessively large breasts (which may necessitate surgical reduction), problems with fertility, and possibly an increased risk of estrogen-dependent cancers later in life.[1]

See also

- Hyperestrogenism

- Aromatase deficiency

- Estrogen insensitivity syndrome

- Congenital estrogen deficiency

- Androgen insensitivity syndrome

- Inborn errors of steroid metabolism

- Disorders of sex development

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Martin RM, Lin CJ, Nishi MY; et al. (July 2003). "Familial hyperestrogenism in both sexes: clinical, hormonal, and molecular studies of two siblings". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 88 (7): 3027–34. doi:10.1210/jc.2002-021780. PMID 12843139.

- 1 2 3 Stratakis CA, Vottero A, Brodie A; et al. (April 1998). "The aromatase excess syndrome is associated with feminization of both sexes and autosomal dominant transmission of aberrant P450 aromatase gene transcription". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 83 (4): 1348–57. doi:10.1210/jc.83.4.1348. PMID 9543166.

- 1 2 3 4 Gregory Makowski (22 April 2011). Advances in Clinical Chemistry. Academic Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-12-387025-4. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- 1 2 3 Fukami M, Shozu M, Ogata T (2012). "Molecular bases and phenotypic determinants of aromatase excess syndrome". International Journal of Endocrinology 2012: 584807. doi:10.1155/2012/584807. PMC 3272822. PMID 22319526.

- ↑ Binder G, Iliev DI, Dufke A; et al. (January 2005). "Dominant transmission of prepubertal gynecomastia due to serum estrone excess: hormonal, biochemical, and genetic analysis in a large kindred". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 90 (1): 484–92. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-1566. PMID 15483104.

- ↑ de Lignières B, Silberstein S (April 2000). "Pharmacodynamics of oestrogens and progestogens". Cephalalgia : an International Journal of Headache 20 (3): 200–7. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.2000.00042.x. PMID 10997774.

- ↑ Meinhardt U, Mullis PE (2002). "The aromatase cytochrome P-450 and its clinical impact". Hormone Research 57 (5-6): 145–52. doi:10.1159/000058374. PMID 12053085.

- ↑ Czajka-Oraniec I, Simpson ER (2010). "Aromatase research and its clinical significance". Endokrynologia Polska 61 (1): 126–34. PMID 20205115.

- ↑ Persson I (November 2000). "Estrogens in the causation of breast, endometrial and ovarian cancers - evidence and hypotheses from epidemiological findings". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 74 (5): 357–64. doi:10.1016/S0960-0760(00)00113-8. PMID 11162945.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||