Affirming the consequent

Affirming the consequent, sometimes called converse error, fallacy of the converse or confusion of necessity and sufficiency, is a formal fallacy of inferring the converse from the original statement. The corresponding argument has the general form:

- If P, then Q.

- Q.

- Therefore, P.

An argument of this form is invalid, i.e., the conclusion can be false even when statements 1 and 2 are true. Since P was never asserted as the only sufficient condition for Q, other factors could account for Q (while P was false).[1][2]

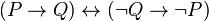

To put it differently, if P implies Q, the only inference that can be made is non-Q implies non-P. (Non-P and non-Q designate the opposite propositions to P and Q.) This is known as logical contraposition. Symbolically:

The name affirming the consequent derives from the premise Q, which affirms the "then" clause of the conditional premise.

Examples

One way to demonstrate the invalidity of this argument form is with a counterexample with true premises but an obviously false conclusion. For example:

- If Bill Gates owns Fort Knox, then he is rich.

- Bill Gates is rich.

- Therefore, Bill Gates owns Fort Knox.

Owning Fort Knox is not the only way to be rich. Any number of other ways exist to be rich.

However, one can affirm with certainty that "if Bill Gates is not rich" (non-Q) then "Bill Gates does not own Fort Knox" (non-P). This is the contrapositive of the first statement, and it must be true if the original statement is true.

Arguments of the same form can sometimes seem superficially convincing, as in the following example:

- If I have the flu, then I have a sore throat.

- I have a sore throat.

- Therefore, I have the flu.

But having the flu is not the only cause of a sore throat since many illnesses cause sore throat, such as the common cold or strep throat.

See also

- Confusion of the inverse

- Denying the antecedent

- ELIZA effect

- Fallacy of the single cause

- Fallacy of the undistributed middle

- Inference to the best explanation

- Modus ponens

- Modus tollens

- Post hoc ergo propter hoc

- Necessity and sufficiency

References

- ↑ "Fallacy Files". http://www.fallacyfiles.org. Fallacy Files. Retrieved 9 May 2013. External link in

|work=(help) - ↑ Damer, T. Edward (2001). "Confusion of a Necessary with a Sufficient Condition". Attacking Faulty Reasoning (4th ed.). Wadsworth. p. 150.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||