Amur falcon

| Amur falcon | |

|---|---|

_male_(16794543415).jpg) | |

| Male | |

.jpg) | |

| Female | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Falconiformes |

| Family: | Falconidae |

| Genus: | Falco |

| Species: | F. amurensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Falco amurensis Radde, 1863 | |

| |

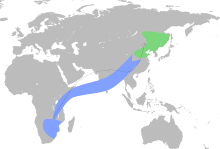

| Breeding Non-breeding | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The Amur falcon (Falco amurensis) is a small raptor of the falcon family. It breeds in south-eastern Siberia and Northern China before migrating in large flocks across India and over the Arabian Sea to winter in Southern Africa. It was earlier treated as a subspecies of the red-footed falcon (Falco vespertinus) and known as the eastern red-footed falcon. Males are dark grey with reddish brown thighs and undertail coverts; reddish orange eye-ring, cere, and feet. Females are duller above, with dark scaly markings on white underparts, an orange eye ring, cere, and legs. Only a pale wash of rufous is visible on their thighs and undertail coverts. Their diet consists mainly of insects, such as termites; during migration over the sea, they are thought to feed on migrating dragonflies. The route that they take from Africa back to their breeding grounds is as yet unclear.

Description

.jpg)

Males are characteristically dark sooty grey above with rufous thighs and vent. In flight, the wing lining is white, contrasting with the dark wing feathers. Adult males of the closely related red-footed falcon have a dark grey wing lining. In Africa, males can be confused with melanistic Gabar goshawks, but the chestnut on the vent is distinctive. Also, there may be some superficial resemblance to the sooty falcon and the grey kestrel, but those two species both have yellow feet and cere. The wings are long as in most falcons (with a span of 63–71 cm) and at rest the wing tip reaches or extends just beyond the tail-tip.[2]

Females can be more difficult to identify as they share a pattern common to many falcons, but are distinctive in having an orange eye-ring, a red cere and reddish orange feet. Juveniles can be confused only with those of the red-footed falcon, but lack the buffy underwing coverts.

Taxonomy

The Amur falcon was long considered a subspecies or morph of the red-footed falcon, but it is nowadays considered distinct. Nonetheless, it is the red-footed falcon's closest relative; their relationship to other falcons is more enigmatic. They appear morphologically somewhat intermediate between kestrels and hobbies and DNA sequence data has been unable to further resolve this question, mainly due to lack of comprehensive sampling.[3][4][5]

Distribution and migration

| Measurements | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| [2][6] | |||

| Length | 275–290 mm (10.8–11.4 in) | ||

| 285–300 mm (11.2–11.8 in) | |||

| Tail | 123–130 mm (4.8–5.1 in) | ||

| 129–132 mm (5.1–5.2 in) | |||

| Head | 41–43 mm (1.6–1.7 in) | ||

| 42–44 mm (1.7–1.7 in) | |||

| Tarsus | 60–62 mm (2.4–2.4 in) | ||

| 65–67 mm (2.6–2.6 in) | |||

| Weight | 97–155 g (3.4–5.5 oz) | ||

| 111–188 g (3.9–6.6 oz) | |||

The Amur falcon breeds in east Asia from the Transbaikalia, Amurland, and northern Mongolian region to parts of North Korea. They migrate in a broad front through India, sometimes further east over Thailand and Cambodia and then over the Arabian Sea, sometimes in passage on the Maldives and other islands to reach southern Africa. Birds going over India are thought to be aided by strong winds blowing westward. These winds are strong at an altitude of about 3000m and the birds are thought to fly at a height of above 1000m during migration.[7] The route taken to return to their breeding grounds is not clear, but they avoid the long ocean crossing and possibly take an overland route northward through Africa and to the west of the Himalayas.[2] Vagrants have been recorded as far west as in Italy, Sweden, St. Helena and the United Kingdom.[6]

Behaviour and ecology

The Amur falcon feeds mainly late in the evening or early in the morning capturing a wide range of insects in the air or on the ground. They capture most of their prey in flight, sometimes by hovering, but will also pick prey by alighting on the ground.[6] The winter diet appears to be almost entirely made up of insects[8] but they take small birds and amphibians to feed their young in their breeding range. The rains in Africa produce swarms of termites, locusts, ants and beetles that provide ample food.[9] Their migration over the Arabian Sea coincides with the timing of the migration of dragonflies (Pantala flavescens) and these are thought to provide food during the most arduous part of their migration route.[10] Their breeding habitats are in open wooded country with marshes. During migration they stay in open forest or grasslands, roosting colonially on exposed perches or wires.[6]

The breeding season is May to June and several pairs may nest close together. Abandoned nest platforms belonging to birds of prey or corvids and even tree hollows are re-used for nesting. Three or four eggs are laid (at two day intervals). Both parents take turns to incubate and feed the chicks which hatch after about a month. The young birds leave the nest after about a month.[6]

The Amur falcon hosts three species of lice, Degeeriella rufa, Colpocephalum subzerafae, and Laembothrion tinnunculi.[11]

Status and conservation

The wide breeding range and large population size of the Amur falcon have led to the species being assessed as being of least concern. The flocking behaviour during migration and the density at which they occur, however, expose them to hunting and other threats. During their migration from their breeding area to the winter quarters, they are plump and are hunted for food in parts of northeastern India as well as in eastern Africa.[1][12] In 2012, mass trapping and capture of migrating Amur falcons in Nagaland (India) was reported in the media and a successful campaign was begun to prevent their killing.[13] As part of this campaign, three birds were fitted with 5 gm satellite transmitters that allowed them to be tracked during their migration.[14]

References

- 1 2 BirdLife International (2012). "Falco amurensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 Rasmussen, PC & JC Anderton (2005). Birds of South Asia. The Ripley Guide. Volume 2. Washington, DC & Barcelona: Smithsonian Institution & Lynx Edicions. p. 113.

- ↑ Wink, Michael; Seibold, I.; Lotfikhah, F. & Bednarek, W. (1998): Molecular systematics of holarctic raptors (Order Falconiformes). In: Chancellor, R.D., Meyburg, B.-U. & Ferrero, J.J. (eds.): Holarctic Birds of Prey: 29–48. Adenex & WWGBP.

- ↑ Griffiths, Carole S. (1999). "Phylogeny of the Falconidae inferred from molecular and morphological data" (PDF). Auk 116 (1): 116–130. doi:10.2307/4089459.

- ↑ Griffiths, Carole S.; Barrowclough, George F.; Groth, Jeff G. & Mertz, Lisa (2004). "Phylogeny of the Falconidae (Aves): a comparison of the efficacy of morphological, mitochondrial, and nuclear data". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 32 (1): 101–109. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2003.11.019. PMID 15186800.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Orta, J. (1994). "Amur Falcon". In del Hoyo, J., A. Elliott, and J. Sargatal. Handbook of birds of the world. Vol. 2. New World vultures to guineafowl. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. pp. 265–266.

- ↑ Clement, Peter; Holman, David (2001). "Passage records of Amur Falcon Falco amurensis from SE Asia and southern Africa including first records from Ethiopia.". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club 121 (1): 222–230.

- ↑ Kopij, Grzegorz (2009). "Seasonal variation in the diet of the Amur kestrel (Falco amurensis) in its winter quarter in Lesotho". African Journal of Ecology 48 (2): 559–562. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.2009.01130.x.

- ↑ Pietersen, Darren W; Symes, Craig T (2010). "Assessing the diet of Amur Falcon Falco amurensis and Lesser Kestrel Falco naumanni using stomach content analysis". Ostrich: Journal of African Ornithology 81 (1): 39–44. doi:10.2989/00306525.2010.455817.

- ↑ Anderson, R. Charles (2009). "Do dragonflies migrate across the western Indian Ocean?" (PDF). Journal of Tropical Ecology 25: 347–358. doi:10.1017/S0266467409006087.

- ↑ Piross, I. Sandor; et al. (2015). "Louse (Insecta: Phthiraptera) infestations of the Amur Falcon (Falco amurensis) and the Red-footed Falcon" (PDF). Ornis Hungarica 23 (1): 58–65. doi:10.1515/orhu-2015-0005.

- ↑ Ali, S & S. Dillon Ripley. Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan. Volume 1. (2 ed.). New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 361–363.

- ↑ Falcon preservationists

- ↑ Boyes, Steve. "Safe Passage For Amur Falcons Through India". National Geographic. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

Further reading

- Adventures in Nagaland and Satellite tracks of three individuals

- How to make 2.5 billion termites disappear? A case for protecting the Amur falcon, Ornithological Observations, an open-content, electronic journal published by BirdLife South Africa and the Animal Demography Unit at the University of Cape Town

- The Great migration of Amur Falcon, The Morung Express

External links

Media related to Falco amurensis at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Falco amurensis at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Falco amurensis at Wikispecies

Data related to Falco amurensis at Wikispecies