Foot whipping

| Part of a series on |

| Corporal punishment |

|---|

|

| By place |

| By implementation |

| By country |

| Court cases |

| Politics |

Foot whipping or bastinado describes a method of corporal punishment, which consists in hitting the undersides of a person's feet.

The receiving person is required to be barefoot. The uncovered soles of the feet need to be placed in an exposed position. The beating is typically performed with an object in the type of a cane or switch. The strokes are usually aimed at the arches of the feet and repeated a certain number of times.

Bastinado is also referred to as foot (bottom) caning or sole caning, depending on the instrument in use. The particular Middle East method is called falaka or falanga,[1] derivative from the Greek term phalanx. The German term is Bastonade, deriving from the Italian noun bastonata (stroke with the use of a stick). In former times it was also referred to as Sohlenstreich (corr. striking the soles). The Chinese term is jiao xing.

The first scripted documentation of bastinado in Europe dates back to the year 1537, in China to 960.[2] References to bastinado are found in the Bible (Prov. 22:15; Lev. 19:20; Deut. 22:18), suggesting the practice since antiquity.[3]

This form of flagellation differs from other commonly practiced methods by concentrating on a small area of the human body. The strokes are aimed at the vaults of the feet only, where a relatively high degree of pain sensitivity is taken advantage of. As the skin texture under the feet is naturally prepared to endure high levels of strain, injuries demanding medical attention are rarely inflicted if certain precautions are observed. The undersides of the feet therefore came to be an obvious target for corporal punishment while diverging methods exist in different countries.

Foot whipping is typically practiced within prisons or similar institutions. It is regarded to be a particularly degrading and oppressive method of punishment. Besides the drastic physical suffering for the victim this refers to the socio-cultural context of this specific form of punishment.

The exposure of bare feet is a ritualistic sign of subjection and a traditional indicator typically of the lowest class within a social hierarchy. It has regularly been imposed as an obstacle and visual identifier on slaves or people having their basic civil rights and liberties revoked. This measure was also often used as part of a shame sanction or for public humiliation.

Foot whipping hereby represents a culmination to keeping a person barefoot, which is often used to display his or her loss of rights and status in itself. The subjection of the person is distinctly showcased and accentuated by this specific form of flagellation. A person who is punished by getting his or her bare feet beaten may therefore lose his or her social standing and be looked upon as inferior by other people. As a result, the victim often feels shamed and abased by this punishment.

Keeping prisoners barefoot is in turn common practice in several countries.

The prisoners are hereby excluded from normally taken for granted items of clothing with their uncovered feet exposed to outside influences. As the feet are the only body part with near permanent contact to the environment, their lack of protection can alone have a victimizing effect and make the person feel physically defeated. The forced exposure often further aggravates sentiments of vulnerability and helplessness typically experienced in situations of incarceration. Beating a prisoner's vulnerable unprotected feet can hereby drastically escalate his or her emotional distress.

This particular means of punishment therefore poses a considerable threat on potential victims and is often exceptionally feared. The high level of intimidation the penalty of foot whipping conveys is in turn often exploited to enforce compliance from incarcerated individuals.[4]

Bastinado is commonly associated with Middle and Far Eastern nations, where it is occasionally executed in public, therefore covered by sparse reports and photographs. However it has been frequently practised within in the Western World as well, particularly in prisons, reformatories, boarding schools and similar institutions.

In Europe bastinado was a frequently encountered form of corporal punishment particularly in German areas, where it was mainly carried out to enforce discipline within penal and reformatory institutions, culminating during the Third Reich era. In several German and Austrian institutions it was still practised during the 1950s.[5][6][7][8] Although bastinado has been practiced in penal institutions of the Western World until the late 20th century, it was barely noticed as there is no reference to ever being adjudged on a high level. Instead it was carried out on a rather low level within the confines of the institutions, typically to punish inmates for misconduct during incarceration. If not specifically authorized the practice was usually disregarded or condoned, happening for the most part unbeknown to the public. Also foot whipping hardly attracts public interest in general as it visually appears unspectacular and insignificant compared to other punishment methods. As it was not executed publicly in the western world, it came to be witnessed only by the individuals immediately involved. At this former prisoners seldom communicate incidents as beating a person's feet is largely perceived as a very shameful punishment (see public humiliation), while former executants are usually obliged to secrecy.

Bastinado is still used as prison punishment in several countries (see below). As it causes substantial suffering for the victim while physical evidence remains largely undetectable after some time, it is frequently used for interrogation and torture in rogue regimes as well.

Appearance

Bastinado usually requires a certain amount of collaborative effort and an authoritarian presence on the executing party to be enforced. Therefore, it typically appears in settings where corporal punishment is officially approved to be exerted on predefined group of people. This can be situations of imprisonment and incarceration as well as slavery. This moderated subform of flagellation is characteristically prevalent where subjected individuals are forced to remain barefoot uniformly.

Regional

Foot whipping was common practice as means of disciplinary punishment in different kinds of institutions throughout Central Europe until the 1950s, especially in German territories.[5][6] During the German Third Reich era it was increasingly used in penal institutions and labor camps. It was also inflicted on the population in occupied territories, notably Denmark and Norway.[9]

During the era of slavery in Brazil and the American South it was often used whenever so-called "clean beating" instead of the prevalent more radical forms of flagellation was demanded. This was the case when a loss in marketable value through visible injuries especially on females was to be avoided. As many so-called "slave-codes" included a barefoot constraint, bastinado required minimal effort to be performed.[10] As it was sufficiently effective but usually left no visible or relevant injuries, bastinado was often used as an alternative for female slaves with higher marketable value.[11]

Bastinado is still practised in penal institutions of several countries around the world. In a 1967 survey 83% of the inmates in Greek prisons reported about frequent infliction of bastinado. It was also used against rioting students. In Spanish prisons 39% of the inmates reported about this kind of treatment. The French Sûreté reportedly used it to extract confessions. British occupants used it in Palestine, French occupants in Algeria. Within colonial India it was used to punish tax offenders. Within penal institutions in Europe bastinado was reportedly used in Germany, Austria, France, Spain, Greece, Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Portugal, Macedonia, Lithuania, Georgia, Ukraine, Cyprus, Slovakia and Croatia. Other nations with documented use of bastinado are Syria, Israel, Turkey, Morocco, Iran, Egypt, Iraq, Libya, Lebanon, Tunisia, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Brazil, Argentina, Nicaragua, Chile, South Africa, Venezuela, Rhodesia, Zimbabwe, Paraguay, Honduras, Bolivia, Ethiopia, Somalia, Kenya, Cameroon, Mauritius, Philippines, South Korea, Pakistan and Nepal.[12]

In history

- In the United States corporal punishment through foot whipping is reported from juvenile penal institutions until 1969, as for example in Massachusetts.[7]

- Foot whipping was practised in juvenile institutions and protectories in Austria until the 1960s.[13]

- In the German Third Reich bastinado was used in women's prisons and labor camps where female prisoners were often kept barefoot uniformly.[14][15][16][17] During and beyond that period of time this form of punishment was commonly used in juvenile institutions in German territories as well.[5]

- British colonial police officer Charles Tegart is said to have instituted foot whipping, a practice derived from the former Ottoman rule, in an interrogation centre established at Jerusalem in 1938, as part of the effort to crush the 1936–39 Arab revolt in Palestine.

- Foot whipping was used by Fascist Blackshirts against Freemasons critical of Benito Mussolini as early as 1923 (Dalzell, 1961).

- It was used as a method of torture during the Greek Civil War of 1946 to 1949 and the regime of the Colonels in Greece, from 1967 to 1974.[18]

- Applied by Soviet Union to Vsevolod Meyerhold in 1939.

- It was reported that Russian prisoners of war were "bastinadoed' at Afion camp by their Turkish captors during World War I. However British prisoners escaped this treatment.[19]

- Foot whipping was, among other methods, used as a method of obtaining confession from alleged political criminals during the communist regime of Czechoslovakia[20]

- Bahá'u'lláh (founder of the Bahá'í Faith) underwent foot whipping in August 1852 as a follower of the Babi religion. (Esslemont, 1937).

- It was used throughout the Ottoman Empire.

- Foot whipping was used at the S-21 prison in Phnom Penh during the rule of the Khmer Rouge and is mentioned in the ten regulations to prisoners now on display in the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum.

- This punishment has, at various times, been used in China, as well as the Middle East.

Modern era

- Foot whipping was a commonly reported torture method used by the security officers of Bahrain on its citizens between 1974 and 2001.[21] See Torture in Bahrain.

- Falanga is allegedly used by the Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP) against persons suspected of involvement with the opposition Movement for Democratic Change parties (MDC-T and MDC-M).[22]

- The Prime Minister of Swaziland, Barnabas Sibusiso Dlamini, threatened to use this form of torture (sipakatane) to punish South African activists who had taken part in a mass protest for democracy in that country.[23]

- Kerala Police is supposed to have used this as a part of torturing Naxals during the emergency period.[24]

- Reportedly used by Assad regime on Syrians in Homs.[25]

- Use phalanx of torturing prisoners has been reported on the status of the dictatorship of Saddam Hussein in Iraq (1979-2003).

- Reportedly used in Tunisia by security forces.[26]

- Recent research in imaging of torture victims confirms it is still used in several other countries.[27]

In literature

- In act V, scene I of the Shakespearean comedy As You Like It, Touchstone threatens William with the line: "I will deal in poison with thee, or in bastinado, or in steel..."

- In act I, scene X of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's opera, Die Entführung aus dem Serail ("The Abduction from the Seraglio"), Osmin threatens Belmonte and Pedrillo with bastinado: "Sonst soll die Bastonade Euch gleich zu Diensten steh'n." (lit. "Or the bastonade will serve you soon.").

- In act I, scene XIX of Mozart's opera The Magic Flute, Sarastro orders Monostatos to be punished with 77 blows on the soles of his feet: "He! gebt dem Ehrenmann sogleich/nur sieben und siebenzig Sohlenstreich'." (lit. "Give the gentleman immediately just seventy-seven strokes on the soles.")

- In Chapter 8, Climatic Conditions, of Robert Irwin’s novel The Arabian Nightmare, Sultan’s doppelgänger is discovered and is questioned. “He was bastinadoed lightly to make him talk (for a heavy bastinado killed), but the man sobered up quickly and said nothing.”

- In Chapter 58 of Innocents Abroad by Mark Twain, a member of Twain's party goes to collect a specimen from the face of the Sphinx and Twain sends a sheik to warn him of the consequences: "...by the laws of Egypt the crime he was attempting to commit was punishable with imprisonment or the bastinado."

- In Tony Anthony's autobiography: Taming the Tiger, he was tortured and interrogated by Cyprian policemen using primarily this method, before being imprisoned in Nicosia central prison.

Methods

The prisoner is barefooted and restrained in such manner, that the feet cannot be shifted out of position. The intention is to avert serious injuries of the forefoot by stray hitting, especially of the fracturable toes. The energy of the stroke impacts is typically meant to be absorbed by the muscular tissue inside the vaults of the feet.

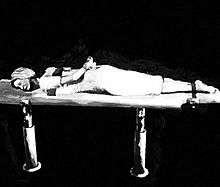

The Middle Eastern falaka method entails tying up the person's feet into an elevated position while lying on the back, the beating is generally performed with a rigid wooden stick, a club or a truncheon. The term falaka describes the wooden plank used to tie up the ankles, however different items are used for this purpose. The essentially different German method, which was practiced until the end of the Third Reich era, consisted in strapping the barefoot prisoner prone onto a wooden bench or a plank. Hereby the feet were forced into a pointed posture (plantar flexion) with their bare undersides facing upward. For this purpose the upper body and both ankles were strapped onto the bench. The prisoner's hands were tied behind the back, usually using a cord or a leather strap. Hereby the person was rendered largely immobile and was especially not able to move the feet out of their forced position. The typically occurring contortions of the body during the execution were largely halted as well. This way the punishment could be inflicted with a certain degree of accuracy to not cause unwanted lesions or other severe injury. It was typically executed with a slightly flexible beating accessory such as a cane or a switch. More infrequently also short whips or leather straps were used. This form of punishment was mainly employed in women's penal institutions and labor camps where prisoners were often kept uniformly barefoot.[8][28]

The middle eastern falaka is more inclined to cause serious injuries such as bone fractures and nerve damage than the German Third Reich method, as the person undergoing falaka can move the body and feet to a certain degree. As a result, the strokes impact more or less randomly and injury-prone areas are frequently affected. As falaka is usually carried out with a rigid and often heavy stick, it accordingly causes blunt trauma leaving the person unable to walk subsequently and often impeded for life. For the Third Reich form the prisoner was principally unable to move and the beatings were performed with lightweight objects that were relatively thin in diameter and usually slightly flexible. The physical aftereffects of the procedure remained mostly superficial and unwanted injuries were relatively rare. Therefore, the person usually remained capable of walking right after the punishment. Still the Third Reich form of bastinado caused severe levels of pain and suffering for the receiving person.

Effects

The beatings usually aim at the tender longitudinal arch of the foot avoiding the bone structure of the ball and the heel. The vaults are particularly touch-sensitive and therefore susceptible to pain due to the tight clustering of nerve endings.

Corporal

When exerted with a thin and flexible object of lighter weight the corporal effects usually remain temporary. The numerous bones and tendons of the foot are sufficiently protected by muscular tissue so the impact is absorbed by the skin and muscular tissue. The skin under the soles of the human feet is of high elasticity and consistence similar to the palms of the hands.[29] Lesions and hematoma therefore rarely occur while beating marks are mostly superficial. Depending on the characteristics of the beating device in use and the intensity of the beatings the emerging visible aftereffects remain ascertainable over a time frame of a few hours to several days. The receiving person usually remains able to walk without help right after the punishment.

When the beating is executed with heavy sticks like clubs or truncheons according to the falaka method, bone fractures commonly occur as well as nerve damage and severe hematoma. The sustained injuries can take a long time to heal with even lasting or irreversible physical damage to the human musculoskeletal system.

When thin and flexible instruments are used the immediate experience of pain is described as acutely stinging and searing. The instant sensations are disproportionally intense compared to the applied force and reflexively radiate through the body. The subsequent pain sensations of a succession of strokes are often described as throbbing, piercing or burning and gradually ease off within a few hours. A slightly stinging or nagging sensation often remains perceptible for a couple of days, especially while walking.

As the nerve endings under the soles of the feet do not adapt to recurring sensations or impacts, the pain reception does not alleviate through continuous beatings. On the contrary the perception of pain is further intensified over the course of additional impacts through the activation of nociceptors. Over a sequence of impacts applied with nearly constant force the perception of pain is therefore progressively intensifying until a maximum level of activation is reached. For that reason a facile impact can already cause an acute pain sensation after a certain number of preceding strokes.

The subjective experience of corporal suffering can however largely diverge according to a person's individual pain tolerance. The pain reception itself is hereby aggravated through feelings of anxiety and agitation. The subjective pain susceptibility is accordingly higher the more apprehensive the individual feels about it.[30][31] Further the female gender generally experiences physical pain notably more intensive and typically reacts with a higher level of anxiety. At the same time women are distinctly sensitive to pressure pain. According to respective assertions women's subjective suffering under the infliction of foot whipping therefore is significantly more severe. The acute pain sensations can hereby be experienced as largely intolerable.[32]

Mental

Seizing and withholding the footwear from a person in a situation of imprisonment, which is commonplace in many countries (Barefoot#Imprisonment and slavery), often has a disconsolating and victimizing effect on the individual. As bare feet are traditionally regarded as a token of subjection and captivity, the unaccustomed and largely reluctant exposure is often perceived as humiliating or oppressive. The increased physical vulnerability by having to remain barefoot often leads to trepidation and the feeling of insecurity. This measure alone can therefore already cause significant distress.[33]

This circumstance is usually aggravated if the bare feet are the target for corporal punishment. The feet are typically hidden away and protected by footwear in most social situations, hereby avoiding unwanted exposure. Therefore, the enforced exposure for the purpose of punishment is mostly perceived as a form of harassment. The obligatory restraints further add to the anxiety and humiliation of the captive.

Any form of methodical corporal punishment typically causes a high level of distress through the inflicted pain and the experience of being defenseless and unable to evade the situation. The mostly occurring loss of composure during the punishment as well as the experience of weakness and vulnerability often permanently damages a person’s self-esteem.

Beating the undersides of a person's feet moreover conveys an especially steep imbalance in power between the executing party (prison staff or similar) towards the receiving individual (typically prison inmate). A rather private area of the body, which traditionally remains covered or not visible in the presence of other people, is forcibly exposed and beaten. This act represents a blunt intrusion into the sphere of personal privacy and an according elimination of personal boundaries. By this means the receiving person experiences his or her individual powerlessness against the executing authority in a particularly manifest way. This experience can also change or deconstruct the individual's self-perception and self-awareness.

As a result, the experience of bastinado leads to drastic physical and mental suffering for the receiving individual and is therefore regarded as a highly effectual method of corporal punishment. Exploiting the effects of bastinado on a person, it is still frequently employed on prisoners in several countries.

See also

- Judicial corporal punishment

- Corporal punishment

- Public humiliation

- Flagellation

- Caning

- Barefoot

- Physical restraint

- Prisoners' rights

References

- ↑ Cfr. Wolfgang Schweickard, Turkisms in Italian, French and German (Ottoman Period, 1300-1900). A historical and etymological dictionary s.v. falaka

- ↑ Torture and Democracy by Darius Rejali. p. 274.

- ↑ "BASTINADO". www.biblegateway.com. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ↑ Arnold, Eysenck, Meili: Lexikon der Psychologie (Encyclopedia of Psychology), Band 3, 1973, S. 476f, ISBN 3-451-16113-3

- 1 2 3 "Wimmersdorf: 270 Schläge auf die Fußsohlen" (in German). kurier.at. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- 1 2 "krone.at" vom 29. März 2012 Berichte über Folter im Kinderheim auf der Hohen Warte; 3 March 2014

- 1 2 Torture and Democracy von Darius Rejali. S. 275.

- 1 2 Ruxandra Cesereanu: An Overview of Political Torture in the Twentieth Century. p. 124f.

- ↑ Torture and Democracy by Darius Rejali. p. 275

- ↑ "Cape Town and Surrounds.". Western Cape Government. Retrieved 14 July 2013. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ Torture and Democracy by Darius Rejali. p. 277.

- ↑ Torture and Democracy by Darius Rejali. p. 275f.

- ↑ „krone.at“ 29 March 2012 Berichte über Folter in Kinderheimen auf der Hohen Warte; 22 February 2014

- ↑ Vgl. Ruxandra Cesereanu: An Overview of Political Torture in the Twentieth Century. S. 124f.

- ↑ Rochelle G. Saidel: 30 October 2013

- ↑ Jan Erik Schulte: Konzentrationslager im Rheinland und in Westfalen 1933-1945, Schoeningh Ferdinand GmbH, 2005. 30 October 2013.

- ↑ Brandenburgische Landeszentrale für politische Bildung:

- ↑ Pericles Korovessis, The Method: A Personal Account of the Tortures in Greece, trans. Les Nightingale and Catherine Patrarkis (London: Allison & Busby, 1970); extract in William F. Schulz, The Phenomenon of Torture: Readings and Commentary, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007, pp. 71-9.

- ↑ Christopher Pugsley, Gallipoli: The New Zealand Story, Appendix 1, p. 357.

- ↑ Kroupa, Mikuláš (10 March 2012). "Příběhy 20. století: Za vraždu estébáka se komunisté mstili torturou" [Tales of the 20th century: For the murder of a state security officer, the communists took revenge with torture]. iDnes (in Czech). Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- ↑ E/CN.4/1997/7 Fifty-third session, Item 8(a) of the provisional agenda UN Doc., 10 January 1997.

- ↑ "An Analysis of the Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum Legal Cases, 1998-2006" (PDF).

- ↑ Sibongile Sukati (9 September 2010). "Sipakatane for rowdy foreigners". Times of Swaziland (Mbabane).

- ↑ "INDIA: Dalit boy tortured and humiliated at a police station in Kerala — Asian Human Rights Commission". Humanrights.asia. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ↑ "Secret footage showing 'torture' of Syrians in Homs hospital". The Daily Telegraph (London). 5 March 2012. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ↑ "Justice en Tunisie : un printemps inachevé". ACAT.

- ↑ http://www.forensicmag.com/articles/2014/08/confirming-torture-use-imaging-victims-falanga

- ↑ AI Newsletter 09-1987 Illustrated Reports of Amnesty International 20 January 2012

- ↑ Lederhaut in „MedizInfo“ about the dermis; 20 January 2014

- ↑ Schmerzrezeptoren in „MedizInfo“ about pain receptors; 20 January 2013.

- ↑ Schmerz und Angst in „Praxisklinik Dr. med. Thomas Weiss“ about intensification of pain through anxiety; 20 January 2014.

- ↑ Schmerzforschung in „GeschlechterStudien“ (gender studies) about pain research; 17 December 2015.

- ↑ "Long hours in a Harare Jail.". BBC News. 1 June 2002. Retrieved 6 October 2014.